She Laughed in My Face, Claiming I Was Never Legally Married to Her Son

Part One

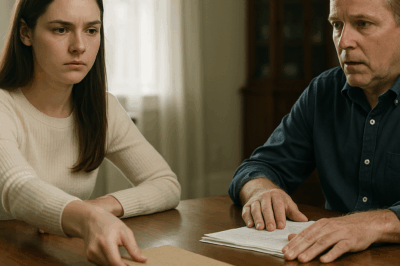

When people talk about the moment their life changed, they usually mean a sunrise—something golden and soft that breaks in quietly and makes the world tender again. Mine was a slammed stack of photocopies on a warm pile of whites and a mother-in-law whose perfume smelled like violets and victory.

“You get nothing in the divorce,” Linda said, and her smirk moved the way a blade does when it knows it won’t slip. “My son never registered your marriage. You’re not even his real wife.”

She waggled a sheaf of documents as if she were a queen making it snow. The pages fluttered and landed on the dress shirts I’d just ironed—David’s collars, crisp as good intentions. I pressed each shirt down again with the heel of my hand and smoothed the fabric as if I had all the time in the world.

“Thanks for letting me know, Linda,” I said, folding another shirt into a perfect rectangle. There was basil in a jar on the sill and late light on the tile. You could have mistaken it for a normal afternoon if you didn’t speak the language of women who’ve learned to keep a whole life steady with their wrists.

She blinked—thrown not by the content of my words but by their temperature. “Did you hear me?” she said, louder. “You’re nothing. Just a woman who played house with my son. When he marries Olivia, she’ll be his real wife.”

I slipped the last shirt into the laundry basket and looked at her. “Is there anything else?”

The shock registered then. It’s an expression I’ve seen on board members when a woman doesn’t flinch on the third interruption. Linda stood there with the papers and a face that couldn’t compute a reaction it hadn’t pre-scripted. She expected tears or bargaining, maybe even hysterics. What she got was a basil plant and a woman laying cutlery with each breath.

“My name is Alexandra,” I added, more for me than for her.

She huffed, recovered, and slammed the papers onto the pile again, as if to mark me with their ink. “When David hands you divorce papers tomorrow,” she hissed, “don’t say I didn’t warn you. Olivia’s already picking out new curtains.”

When her car pulled out and the little theater of it all stopped vibrating, I exhaled. Then I picked up the top sheet, the one with the bolded stamp from the county, and laughed once, a sharp sound I barely recognized as mine. It’s a particular kind of humor—the kind you hear from women who’ve been underestimated for so long they built escape hatches while everybody else was practicing flourish.

I wiped my hands on a dish towel and dialed a familiar number.

“I was wondering when you’d call,” Margaret said, skipping hello the way people do when your lives are threaded together in the places most people can’t see. Margaret had been my mother’s best friend and then the lawyer who filed my mother’s estate and then the woman who taught me to carry two kinds of bags—one for groceries and one for truth.

“It’s happening,” I said, watching a sparrow light on the garden fence. “Linda just told me the marriage was never registered. David’s serving divorce papers tomorrow.”

“And the proof?” she asked.

“Still in the safety deposit box,” I said.

“Smart girl.” Those two words landed like hands on my shoulders from a mother no longer here. “We have everything we need—joint accounts, property titles, your emails for the Paskett bid, and,” she added, the smile audible in her voice, “the contract he signed three years ago when he wasn’t reading and needed your help before the Anderson merger. Linda made a mistake showing her hand so early.”

“Linda doesn’t know the game has more than one player,” I said.

The front gate clicked. David was home—early, which was in itself a kind of confession. I hung up and stirred the sauce as if nothing about the room had shifted.

“Alex,” he said from the doorway. The voice was unsure in a mouth that was used to taking up space.

“I’m making your favorite,” I said, tasting and salting like muscle memory.

He stepped in, then back, as if the kitchen contained weather. “We need to talk.”

“About the divorce papers?” I asked. “Or the part where you never registered our marriage?”

His face lost color the way milk does when you stir in too much ice. “How did you—”

“Your mother told me,” I said. I plated a spoonful and set it on the counter for him. He didn’t taste it.

“It’s not what you think.”

I looked at him then. The man I had loved and landscaped a life with. He had the same hands as when he planted the lilacs our first spring. He also had a new habit of checking his phone when he thought no one noticed.

“Let me guess,” I said. “She convinced you it was for the best. Just a way to protect family assets. Nothing personal. You missed a signature on your way to the golf course.”

His mouth opened, then shut. He stepped closer. “Alex, please. You have to understand.”

“Oh, I do,” I said, back to the simmering pan. “I understand you and your family lied to me for eight years. You’re leaving me for your secretary. And you all think I’ll walk away with nothing.”

A flash of relief crossed his face then—absurd, illuminating relief. A man will relax even in confession if the script requires only that you weep and accept a check.

“I’ll help you,” he offered quickly, as if he were offering me a ride. “We can do a small settlement. First and last month’s rent. You’ll be okay.”

“That’s very thoughtful,” I said. “Will you be staying for dinner?”

“You’re being weird,” he muttered, retreat already in his posture. “I’m… I’ll grab something.”

“Eat while it’s hot,” I said to the empty doorway, more to myself than to him. Tomorrow would be interesting.

After he left, I ate slowly, standing at the counter the way you do when you don’t want the night to notice you. I packed an overnight bag—two dresses, documents I didn’t want in the house, my mother’s locket—and made a final call.

“Officer Martinez,” I said when he answered. “It’s time.”

“I’ve kept the file close,” he said. “You sure?”

“Absolutely,” I said. “Make copies of everything. Bring a set to Margaret. I want Linda to recognize her sentences when she hears them out loud.”

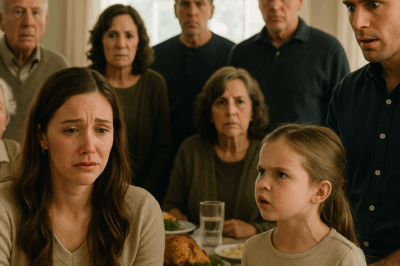

I was already in the conference room at Margaret’s office when they came in—David in a suit too new for a morning meeting, Linda in a dress that said approximation of queen, Thomas in a tie so tight it read repentance, and Olivia hovering with a folder and a perfume that wasn’t mine.

“What is she doing here?” Linda snapped to Margaret as if I weren’t in the room.

“Good morning to you, too,” Margaret said pleasantly, then nodded at the chair. “Please sit. You’ll want your hands free.”

“This is a mere formality,” Linda said, sliding a paper across the polished table with manicured confidence. “Alexandra’s little performance has gone on long enough. The marriage was never registered. We’re here to confirm and move forward. This meeting is for our records.”

“Wonderful,” Margaret said, laying her palm on the table as if it were a stage. “Then let’s make sure we get everything right for the record.”

David gave me a look that said don’t make a scene and then slid the same paper toward me with a sigh: a letter from the county noting no record of a marriage. Linda had underlined a sentence in orange marker in case anyone missed it.

“Shall we start?” Margaret asked.

I reached into my bag and placed a tidy stack onto the table. It wasn’t dramatic. Preparation is a quieter form of violence.

Linda blinked. “What’s that?”

“Everything you did and everything I didn’t,” I said.

Margaret lifted the first page. The stamp caught the light. “Certified copy of the marriage registration,” she said, and the word certified turned my kitchen basil into a wreath.

“That’s impossible,” Linda said. “I had it removed. I—” She cut herself off, too late.

“You removed a copy you signed for,” I said, “from the registrar’s tray when you dropped off the packet for us as a favor.” I smiled at her because sometimes manners are a weapon and a shield. “I filed the original myself. I drove it down. Margaret notarized the affidavit. Officer Martinez witnessed the submission. I know exactly what the file clerk wore that day.”

Margaret slid the second sheet forward, then the third. Bank records with both our names. Property titles with mine. A document that had made me laugh the night I found it in the digital corporate library: an internal memo David wrote to HR praising my analysis on the Paskett bid and insisting my consulting hours be billed at the executive rate even though he planned to pay me in wine and presence.

Thomas shifted in his chair. “Those are internal messages,” he said, the objection thin even to his own ears.

“They became evidence,” Margaret said evenly, “the minute your sister-in-law tried to defraud my client.”

David’s jaw clenched. “Even if the marriage is valid,” he said, “I’m still divorcing her. She’ll receive a basic settlement. We’ll be generous. This is absurd.”

“About that,” I said, and placed the contract on the table like a father casting a line on a calm lake. His eyes fell on his own signature and his face told me he was remembering. Three years ago, a night at the kitchen table, the Anderson merger in danger, a deadline, and me rewriting the purchase terms with a pen while he paced. He’d signed the acknowledgement page without reading it.

“Fifty percent?” Thomas asked, grabbing the document. “You signed this?”

“He needed my help,” I said, not unkindly. “You needed my help, too. You just didn’t think you’d ever need my name.”

Linda’s composure cracked. “We can make a deal,” she said too quickly, leaning forward like a woman at a craps table. “Name your price.”

“I believe you already did,” I said. “It was ‘maybe help with rent.’ I think I’ll go with everything I’m entitled to under the law instead.”

Olivia finally spoke. “You told me it would be simple,” she said to David, her voice somewhere between fear and calculation.

“Nothing about this has been simple,” I said to the room, “because nothing about me has been simple. You mistook my kindness for compliance. You mistook my silence for ignorance. You mistook a woman managing a household for a woman who doesn’t know how to manage a board.”

Linda’s face flushed the color of a storm. “You’re destroying this family.”

“No,” I said, gathering my bag. “You destroyed it the moment you built part of it on a lie and told the rest of us to eat dinner. I’m just refusing to live in your house.”

As I reached the door, David said my name the way a person says please without a speech after it. I kept walking. The truth makes the hallway brighter.

In the elevator, my phone buzzed: Everything go as planned? Officer Martinez.

Better, I typed. Thank you for keeping my mother’s voice safe until I needed it.

Three months after that meeting, I sat in a corner office I hadn’t expected to want. The Harrison Industries logo looked the same on the building; it meant something different in my mouth. The board had required three rounds of soothing and two rounds of numbers. I brought both. We’d increased international revenue by twenty percent on my first pass through the division’s contracts. Turns out the market appreciates clean math more than it likes messy legacy.

Thomas knocked and stepped in, looking as if he hadn’t slept well in weeks. He held a folder like it might bite him.

“Quarterlies,” he said, placing the papers on my desk. “Another twenty percent. You were right about the Newfield exit.”

“Thank you,” I said, skimming. “What else?”

He sat, an old arrogance punctured into something like humility. “I owe you an apology,” he said. “I should have known. I let Linda’s fear become the family’s strategy. You wanted to build. We locked the gate.”

“The irony,” I said, “is that I would have helped build that gate if you’d handed me a hammer instead of a blindfold.” I closed the folder. “How is he?”

“Struggling,” Thomas said. “Olivia left last week. The reality of a reduced trust fund fell short of the fantasy of a CEO’s wife.”

I didn’t allow myself schadenfreude. Joy wears better when you don’t lace it with someone else’s lesson.

“And Linda?” I asked.

He exhaled. “Cruising,” he said, and we both let that word mean what it needed to mean. Hiding. Networking. Pretending the headline was about the economy.

When he left, I stood at the window and let the city’s hum recalibrate me. The desk held a magazine with my face on it and a headline I didn’t recognize myself in. “Resilience and Innovation.” I flipped it over and set it down. My phone buzzed: Dinner tonight? from Margaret. Bring good news.

I had it. An envelope sat in my drawer—the buyout offer. We’d drafted it carefully and padded it with options so it looked like mercy and read like inevitability. I’d keep Thomas on as an adviser because counsel earned through error is a particular kind of useful. I’d buy out the remaining family shares, including David’s trust stake. I’d keep the company name for two years to soothe the market and then rebrand with a quieter story.

Some people will tell you the cleanest revenge is a courtroom. I think it’s a well-run company with childcare for its employees and a board that hears a woman’s sentence without asking who is coming to speak after her.

I slid the envelope back into the drawer and grabbed my coat. On my way out, the receptionist stopped me. “Ms. Harrison,” she said. “Your mother called. She asked that you call her back about a ‘BA offer’—something about continuing the family brand.”

“BA,” I repeated. “She means ‘buyout offer.’” I smiled. “Tell her we’ll be in touch through counsel.”

In the car, I let the day settle. My mother’s best friend had taught me two ways to breathe: through chaos and through quiet. Both got me to Margaret’s table.

“You look lighter,” she said, pouring wine. “Tell me you finally did the thing we planned to do the night you called me from your kitchen with basil on the sill.”

“I did,” I said. “The board will sign next week. Thomas will stay. The rest will go.”

“And then what?” she asked.

“Then we rebuild,” I said, and felt the true answer beneath that: Then we rest. “Also,” I added, pulling another envelope from my bag and tapping it on the linen, “I’m buying a small tech firm David has failed to court for two years. Not because he wanted it. Because I do.”

She lifted her glass. “To new beginnings,” she said.

“To karma,” I said, clinking.

I won’t tell you I didn’t grieve. Grief is a weight you carry in your wrists when you’re editing a spreadsheet and in your ankles when you’re walking from a room someone used to be in. I grieved the eight years I’d spent replanting lilacs and learning how David took his coffee and believing loyalty was a currency that always buys something. Sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes loyalty is a letter you write to the person you’ll become and sign at the bottom with the name everyone kept trying to edit.

I set up a scholarship in my mother’s name with a clause I wrote myself: For women who left and learned. The eligibility required no essay—just a copy of a lease that started with a day in a suitcase.

Linda sent a text the week the buyout papers landed in their mailbox. We need to talk about the BA offer. I put my phone on Do Not Disturb and sat with the silence like it was a friend.

The plant in the kitchen window at home was rosemary now, not basil. It felt like the right herb for a woman who could be both anchor and blade. I watered it and drafted a memo about mental health days for the warehouse team and realized I was writing the kind of sentence I’d wanted to read at twenty-three in a staff handbook and didn’t. There’s something holy about making policies out of promises you didn’t get.

Margaret squeezed my hand at the end of dinner. “Your mother would be proud,” she said, and I believed her not because the sentence was comforting but because the woman who said it had held my mother’s grief and mine.

On my way home, I drove a street I hadn’t driven since everything cracked. The house where Linda had announced my erasure sat with its lights on, looking like an apology it hadn’t learned to say. I didn’t stop. You can reconcile the past without revisiting the porch.

When people talk about the moment their life changed, they make it sound like a sunrise. Mine was a slammed stack of photocopies on a laundry pile and a mother-in-law who thought a safety deposit box was a place you put trinkets, not truths. But change isn’t only a light breaking; it’s also a woman who files the paperwork ahead of time, who records the sentences other people will pretend they never said, who makes a sauce and sets a table and refuses to give a performance she didn’t agree to.

David once told me I was too calm in crisis. He meant it as a criticism. I decided to take it as a crown.

When the board signed and the shares transferred and the magazine dropped to the bottom of a waiting room pile, I stood in my office and watched the city move. I thought of the girl in a white dress walking into a courthouse with basil on her breath and Margaret at her elbow and a file in a cop’s hand. I thought of the lilacs blooming despite neglect. I thought of Linda’s smirk and how, if you look at it right, it’s really just a woman who hasn’t learned yet that some of us carry two bags: one for groceries and one for truth.

I turned off the light and locked my door. The night wasn’t a sunrise. It was steadier than that. It was a woman in her own name, going home.

Part Two

The first time I stood in front of the full board alone, I wore navy and a mouth that didn’t tremble, hair pulled back the way my mother had done for court when she knew she’d win. The mahogany table looked like a pond that believed it was a river. Faces reflected in it—some familiar, some merely fatigued—watched me with a kind of wary respect.

“Before we begin,” I said, “we need to talk about the thing we all pretended wasn’t happening while it was happening. You’ve known for years where the leaks were. You just preferred the wallpaper.”

A few of them smiled; a few didn’t. The fourth-quarter slide deck behind me showed numbers and a headline I wrote for myself: We are not our old story.

We voted, and then we worked. Leaks patched. Contracts rewritten. HR given teeth and a spine. I hired women who’d been told they were “too intense” and men who’d learned to listen. We added childcare stipends for line workers and brought in a trauma-informed counselor twice a month. I discovered the electric intimacy of the break room at shift change, learned more about supply chain from the woman who handled pallet scheduling than I had from a decade of executive memos. Respect isn’t a speech; it’s a schedule.

I didn’t hear from Linda for weeks after the buyout offer hit her mailbox. Not directly. Her messages came through wealth managers and cousins with tight smiles and Christmas card rules. She resurfaced the way weather does—first as rumor, then as a gust.

When she finally did call, she got my voicemail. “We need to discuss the BA offer,” she said briskly. It was the same tone she used to request a refund from boutiques. The message ended with exactly zero sentences that sounded like a mother.

Margaret drafted the addendum to the offer. We included a clause that allowed Linda to exit with a face-saving narrative and a non-voting philanthropic seat on a foundation board if she wanted it. Mercy is not weakness; it’s architecture. She took it, of course, and let society pages write about her pivot to philanthropy as if she’d orchestrated it. I sent flowers to the launch. Orchids. In my card I wrote only, thank you for your service.

David and I signed the divorce papers on a Tuesday morning that smelled like rain and copier ink. The judge was a woman with eyebrows that didn’t move and a gavel she used like punctuation. David didn’t look at me when we stood before the bench. He stared at the bar of light on the floor and tugged at his cuff like it might produce a different sentence.

The distribution was clean because my paper trail was. I didn’t want his apology by then. I wanted out. Half the house, half the liquid assets, half the business until the buyout completed, a cash sum equal to my deferred compensation for eight years of free labor—paid not in installments but in a single wire that landed like closure. We kept our rings until three days later when I drove to a jeweler who knew how to treat gold like memory.

“What would you like to do?” he asked, his tone careful.

“Melt them,” I said. “Make a signet ring. My mother’s initials. Not because I’m sentimental. Because I want the old metal to hold a new name.”

He nodded as if this weren’t the first time a woman had alchemized her life on his counter.

Olivia called once from a number that wasn’t his. “I didn’t know,” she said when I answered without thinking. “He told me the paperwork was done, that you were… over.”

“He tells a lot of women a lot of things,” I said evenly. “I wish you gentler truths in the future.”

“Do you ever miss him?” she asked then, small.

“I miss the version of me that didn’t know the difference between loyalty and self-erasure,” I said. “That’s not the same thing.”

She breathed out and hung up. Months later, I saw her across a lobby with a portfolio under her arm and a mouth set like a decision. She didn’t see me. I was glad for both of us.

The buyout closed in spring when the wisteria on our building trellis thickened enough to make the whole block smell like old ladies and prom nights. Thomas signed last. He did it with a dignity that surprised me and then stayed on three days after the check hit to hand me a dog-eared notebook of old vendors and their quirks.

“The man at Claymore Steel likes to talk about his tomatoes for six minutes before he’ll discuss freight,” he said. “You can save yourself time by timing your call.” He paused. “I know timing now.”

I found him outside later by the fountain, watching three pigeons fight over a pastry someone had dropped. “My sister,” he said without looking at me, “will never forgive me for choosing competence over nostalgia.”

“She’ll forgive you,” I said. “For a cruise.”

He laughed, a sound that had the shape of relief.

I didn’t think about David until a month later when a court notice arrived informing me of a hearing. Linda had petitioned for an injunction to block the publication of a profile on me scheduled for the business journal. “Defamation,” the brief said. “Invasion of privacy.” It was a tactic, not a case.

The courtroom was half full. Reporters sat in the back with legal pads they didn’t really use anymore. Margaret’s associate handled the argument, flicking through exhibits like songbooks. Linda wore black and a grimace that looked rehearsed. David stared at his lap. When the judge asked if anyone wanted to be heard before she ruled, a woman in the second row stood, unbidden.

She wore a navy shift and sensible heels, and her hand shook exactly once as she held up her phone. “I’m a deputy clerk at the registrar’s office,” she said, voice soft but steady. “Eight years ago, a woman came in with a marriage registration. The man who picked up his copy later didn’t file it. We flagged the file because we were missing our stamp on the duplicate intake. The woman came back the next day with her attorney and a police officer and filed it again properly. I remember because it was the first time I saw a bride bring her own witness to protect herself.”

She sat. The room absorbed her. The judge banged her gavel exactly once. “Motion denied,” she said. “Court is not a PR firm.”

I walked out into a light rain. The deputy clerk caught up with me under the overhang.

“I never forgot you,” she said. “You had basil in your bag.”

“Thank you,” I said. “For seeing me then.”

The journalist ran the profile. It wasn’t fawning. It was factual in a way that felt like respect. We took the cover photo in a factory aisle at shift change, and I refused a blazer in favor of a bright work jacket that made me look more like me. The only quote I insisted on was the last line: Calm in crisis is not detachment. It’s a plan you built while they thought you were just stirring the sauce.

The day the story hit, Linda’s charity board announced a new initiative to provide business attire to women returning to the workforce. “A cause close to our hearts,” the press release said. I wrote a check with a quiet smile and sent it through Margaret’s foundation. Let people keep their faces if they’re willing to use them to help someone else. That was a piece of my mother talking through me.

I made a practice of choosing public kindness when it didn’t cost private truth.

On the anniversary of the day Linda slammed the papers on my laundry, I drove to the tiny cemetery upstate where my mother sleeps under a maple and a line of birds that looks like a script. I took basil and rosemary and a paper bag of letters I wrote to the version of me that kept every receipt but forgot sometimes to praise herself for the elegant math.

A woman was kneeling by a grave two rows over, tucking fresh violets into the soil. She watched me water the herbs and said, “You don’t see people bring basil to cemeteries.”

“She used to put it in everything,” I said. “Even eggs.”

“She must have been something,” she said.

“She still is,” I said.

I didn’t go back to the old house again. The shell company listed it. A couple from Ohio bought it—a young teacher with a canvas tote and a pediatric nurse with kind eyes. They sent me a letter through the agent a month after closing, addressed to “the previous owner who left the lilacs.” They wrote how their toddler learned the word purple there. I cried in my car and then forwarded the note to Margaret with a heart because sometimes that’s the whole story.

I moved out of the big house that held evenings I didn’t want anymore into a place with high windows and a kitchen that looks brave. I planted rosemary in a long box and learned that quiet has different flavors. The signet ring fit my hand like an answer. I wore it to a small ceremony at a community center the week we launched the scholarship fund in my mother’s name. Ten women stood in a line—one with a baby, one with a GED class certificate, one with a nurse’s badge she tucked into her pocket for the photo.

“Tell me what you needed when you were twenty-three,” I asked each of them, “and I’ll try to build the thing that would have made the difference.”

“Someone to call at 2 a.m.,” one said.

“A boss who didn’t think my crisis was impolite,” another said.

“Childcare that didn’t judge,” said the woman with the baby.

We built all three.

Officer Martinez retired in fall and invited me for coffee. He brought a shoebox of old notebooks and a coin my mother had given him after a case he helped her with when I was thirteen. “She was stubborn,” he said, smiling into his mug. “You’re precise.”

“I learned from two of you,” I said.

He handed me a photocopy from his file—a page from Linda’s voice mail transcripts. You can’t play nice with women like Alexandra or they’ll take your good coat. I folded the page once and then again, then asked if I could keep it.

“Why?” he asked. “You already won.”

“It reminds me,” I said. “That other people’s fear of your coat is not a reason to take it off.”

We left the café and stood on the sidewalk as if we’d stumbled into the end of a movie. “You ever going to forgive them?” he asked, not unkindly.

“I’m going to forgive myself for believing them,” I said. “That’s enough.”

David sent a last message in winter: a photo of a project I spearheaded ten years ago in a drawer of his apartment. A note. You were right about practically everything. He didn’t ask to see me. I didn’t offer. Some bridges must exist only in the past tense so you remember the geography that taught you to swim.

A year from Linda’s papers and David’s empty plate, I sat on a panel at a women in leadership conference and told a room of executives that contingency planning is not cynicism; it’s intimacy with reality. During the Q&A, a young woman in the third row with a work jacket and a wrist tattoo asked how to protect herself without becoming hard.

“Document everything and water your basil,” I said, and the room laughed and then wrote it down because they understood I wasn’t joking.

On my way out, an older woman stopped me near the ballroom doors. “My mother-in-law told me the day we announced our engagement that I’d never be a real wife,” she said, her voice equal parts salt and silk. “She said paper was a prop.”

“What did you do?” I asked.

“Filed two copies and mailed one to myself,” she said. “With tracking.” We both grinned like thieves who’d learned carpentry.

At home, I cooked eggs and tore basil and rosemary into them and ate them standing at the counter, feeling like a woman not waiting for the sun but being it. Margaret texted me: a photo of a girl at a community college library wearing a lanyard that read our fund name. First day, the caption said. I sent back a record of a wire transfer and a heart.

You might ask if there’s a happier ending in which Linda cries at my wedding or David repents into a man who brings me tea. There isn’t. Sometimes closure is an office you run well and a rosemary plant that doesn’t die when you forget to water it for a day. Sometimes it’s a signet ring that looks like your mother changed her name to yours.

Sometimes the person who told you that you were nothing hands you the papers you needed to prove you were everything you said you were.

I close the office door most nights now with a hand that knows how to hold two things at once—grace and a ledger. Calm in crisis isn’t detachment. It’s the work you did when nobody believed your ring had weight or your name had teeth. It’s learning that the safest deposit box is the one you built in your spine.

Linda once laughed in my face and told me I was never legally married to her son. I tell my mentees this now: the law is a file, yes. But it’s also a woman who files it.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money’

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money,’ Brian Kilmeade passionately defended Erika Kirk on…

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent. CH2

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent Part One The rosemary lamb went…

BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions in his final statement and unexplained evidence have shocked the public: Is Robinson blaming someone else?….read more below

💥 BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions…

“I Stared At The Photo—My Son Did This?” — A Sheriff’s Father Breaks His Silence On Utah’s ALLEGED KILLER

At a $600,000 family home in Washington, Utah, a veteran lawman dialed the number no parent imagines: he turned in…

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire : Ava Raine, the daughter of Hollywood legend Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, has ignited one…

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale. CH2

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load