“SHE CAN BARELY HOLD A JOB!” MY MOM TESTIFIED AGAINST ME. THE CHIEF JUSTICE STOOD UP: “SHE’S BEEN…”

Part One

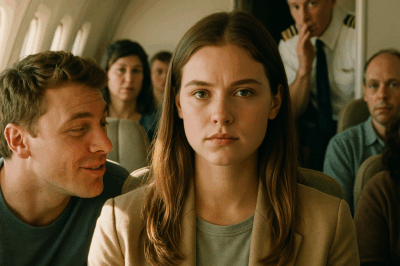

The first thing you learn about courtrooms—if you spend any real time in them—is that silence has flavors. There’s the respectful hush that hangs in the room before the judge takes the bench. There’s the polite quiet of lawyers pretending not to hear one another’s small talk. And then there’s the kind of silence that lands like a thrown brick—when somebody says the one thing you told yourself nobody would ever say out loud.

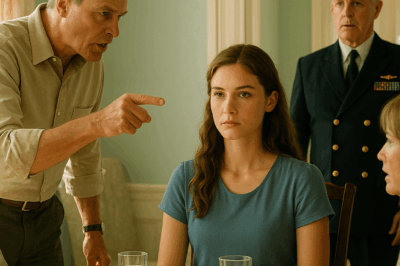

“She can barely hold down a job.”

The words weren’t spoken by my ex-husband’s attorney, or some paid expert with a tidy invoice and a rehearsed opinion. They were spoken by my mother. Into a microphone. On the witness stand. For the record.

My name is Rebecca Hayes. I am thirty-nine years old, and what I do for a living—what I’ve done for the past fifteen years—is sit in rooms that measure words and assign them weight. I know how sentences can shift outcomes, how one phrase can draw a line that becomes a wall. But I would be lying if I said I didn’t feel that sentence hit me in the sternum when my mother said it.

“Your Honor, my daughter has always been… unstable,” she continued, warming to the role she’d already convinced herself was righteous. “She disappears for days at a time. She says she’s working, but there’s never any steady job—nothing you could call stability. Frankly, I don’t think she should have custody of my grandson at all.”

This was a custody hearing, but it was also a theater, and everyone knew their lines. My ex-husband, Marcus, sat at counsel table with his silk-tied lawyer—chin lifted just enough for the reporters in the back row to get the right angle—while my eight-year-old son, Tyler, sat in the front row between my sister and a court officer, trying to pretend his grandmother’s voice did not sound like a verdict.

I wore what I always wear when I need the room to look at my words instead of my clothes: a navy blazer that could have been from any store, a white blouse, hair pulled back so that nothing about me made noise except my voice. The wedding ring had been off for six months, but the pale band on my finger still glowed under the overhead lights, a ghost sentence where a promise used to be.

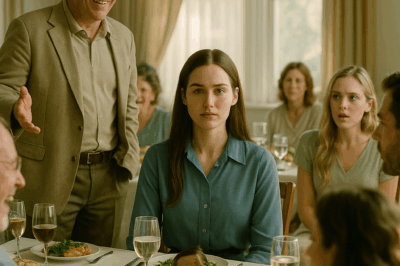

“Your Honor,” Marcus’s lawyer, James Crawford, purred when my mother stepped down, “you’ve heard testimony about the mother’s inability to provide stability, her secrecy about her work, her erratic schedule. We submit that the best interests of the child point unequivocally to awarding full custody to my client.”

Fifteen years in judicial rooms had taught me the most important thing about timing: you don’t stand when someone shoves you. You stand when the floor is yours.

“Ms. Hayes,” Judge Patricia Morrison addressed me, face unreadable, voice even, the same way she’s been for every lawyer who’s ever stood at her podium. “Do you have a response to these allegations about your employment and your ability to parent?”

The gallery leaned forward. Marcus’s lawyer leaned back, already savoring his headline. My mother folded her hands like a nun. She didn’t look at me.

I stood.

“Your Honor,” I said, “I’d like to call a witness.”

Crawford bristled. “We were not notified of any witnesses, Your Honor.”

“The witness was not available until this morning,” I replied. “His testimony will clarify the questions raised.”

Judge Morrison tilted her head, the smallest movement in the room. “Proceed.”

I walked to the double doors at the back and opened them. A murmur rose before he even stepped in. There are people who carry their authority like an overcoat. Then there are people who wear it like skin.

“Your Honor,” I said, “I call Chief Justice William Barrett.”

It wasn’t a gasp so much as the sound a room makes when every person in it inhales the same breath. The Chief Justice of our State Supreme Court strode to the witness stand, took the oath without flourish, and sat, the weight of three decades of law gathering in the air around him like weather.

“Chief Justice,” I began, my voice moving into the register I reserve for work, not family, “could you please identify me for the court?”

He turned to face me, eyes warm in a way he never allows in chambers. “You are the Honorable Rebecca Hayes,” he said, and if there’s any sentence in my life that felt like a benediction, it was that one, “Associate Justice of the State Supreme Court, where you have served with distinction for the past eight years.”

The word Justice landed in the room like a new floor being revealed under an old carpet. People blinked. Papers paused. A reporter in the back forgot to breathe.

“And could you describe the nature of my responsibilities?” I asked.

“Justice Hayes sits on our appellate panels for complex civil and criminal matters,” he said. “She’s chaired the Judicial Ethics Committee for the past four years. She has authored multiple landmark decisions on custody, child welfare, and parental rights. She is, in my view”—he glanced at the judge, courtroom formalities keeping him from adding with the court’s permission—“one of the finest legal minds I’ve encountered.”

She’s been…

He let the sentence rest on the bench like a book you know you’ll quote again.

Marcus’s lawyer looked like a man who’d bet on the wrong horse and hadn’t discovered it until the starting gun. My mother’s face washed from certainty to confusion to something that would sting later when she told herself the story of her righteousness. Tyler’s eyes were on me. That was the only pair that mattered.

“Chief Justice,” I said, “there were questions raised about my financial stability. Would you address them?”

He nodded. “All financial disclosures for sitting Supreme Court justices are public,” he said. “Justice Hayes has complied with every requirement. Her salary is one hundred ninety-five thousand dollars per annum, plus benefits. She owns her home downtown and a small vacation property in Sevier County. There is no evidence of financial instability.”

I looked at Judge Morrison. “With the court’s indulgence,” I said, and the phrase tasted strange in a room where I usually wore the robe, “I would like to explain why my family did not know the particulars of my employment.”

The judge nodded.

“Eight years ago, when I accepted my appointment, I made a decision,” I said. “Not to hide what I am ashamed of—I’m not ashamed of any of it—but to build guardrails between my work and my son’s childhood. Judges’ lives become public in ways that do not benefit children. I wanted Tyler to know his world by smell and sound—grass on school fields, pencil shavings, dogs on sidewalks—without every parent at drop-off telling stories about what his mother decided the day before. So I kept my work… not secret, but quiet. To most people, I worked ‘at the courthouse.’ That’s all.”

In the front row, my sister looked at her hands. My mother was very still. If she had ever asked me, I would have told her. She never did.

Chief Justice Barrett cleared his throat. “If I may, Your Honor,” he said, and the judge inclined her head. “Justice Hayes is a private person. Not in a way that hinders this court, but in a way that honors the children whose names cross our docket. I have watched her write opinions that keep families together or separate them for safety. She has been—” He glanced at me and finished in a sentence intended to suture the room back together. “—she’s been what we ask judges to be when no one is watching.”

It’s not often you hear relief as a sound. It happened then—a low exhale that moved through the courtroom like a slow wave. Even Marcus’s lawyer stopped riffling his papers.

“Your Honor,” I said to Judge Morrison, “I have here my performance evaluations, my latest financial disclosure, and the court-appointed custody evaluation from Dr. Sandra Williams.”

The judge flipped through them, eyes narrowing in satisfaction at the neatness of the record. “Dr. Williams rates you an ‘exemplary parent with strong bonding and appropriate limit-setting,’” she said. “There are no concerns about your capacity to provide. The father’s report indicates a pattern of undermining the mother’s role and minimizing her schedule constraints. Noted.”

Marcus tried to rise and speak. “She never told me—” he began.

I looked at him. “You never asked.”

He sat down.

“Your Honor,” I continued, “I have spent fifteen years protecting children from being weaponized by their parents. I have seen love used as leverage and truth used as furniture. My son is not a bargaining chip. I am requesting full physical custody with supervised visitation for the father until he completes co-parenting classes.”

“And the mother’s mother?” the judge asked without looking at mine. “Her testimony today was… concerning.”

“All future discussions about custody should be conducted without extended family involvement,” I said. “Those who testified today have shown themselves willing to substitute assumption for evidence. My child will not be made a stage.”

Judge Morrison set her pen down. “So ordered,” she said. “Full custody to the mother. Supervised visitation to the father for six months, subject to completion of programming. The grandmother’s testimony is stricken as speculative and prejudicial. This court is adjourned.”

The gavel fell. Tyler launched into my legs, arms tighter than anything. “Mom,” he said into my waist, voice shaky with relief, “you’re a judge?”

“I’m your mother,” I said, kneeling so my face was level with his. “The rest is just how I pay for snacks.”

He smiled in a way I will try to describe for the rest of my life and fail. “Do you send people to jail?”

“Sometimes,” I said. “Mostly I help families figure out what taking care of each other looks like.”

My mother approached like a storm that has lost its thunder.

“Rebecca,” she said softly, and there were years in that syllable, “I… had no idea.”

“That’s the point,” I said, not unkindly. “You never had an idea because you never asked for one.” Her eyes filled but did not spill. There are so many kinds of tears in this world. I did not have bandwidth for any more that day. I turned to Tyler. “Let’s go home.”

We walked out past the reporters, past Marcus’s lawyer explaining to a stenographer that “new information emerged,” past people we will never see again who will still tell this story to their friends. Chief Justice Barrett touched my elbow briefly as we reached the corridor.

“Justice Hayes,” he said, voice back in its official register, “I hope this does not lessen your sense of the bench.”

“On the contrary,” I said. “It reminds me that what we do might be the last stop on someone’s story.”

We stepped into a sun that did not ask for anyone’s permission to shine.

I did not write my life small after that. The next morning, I drove Tyler to school and walked him to his classroom without answering emails. I took him for donuts on the way and said yes to a chocolate one and no to a second. He told me he wanted to be a zookeeper until he was twelve and then an engineer. I told him both jobs involve cleaning up more than people realize.

In chambers, I told my clerks what had happened, briefly and without drama. “It won’t affect our work,” I said. “It will inform it.” We returned to a docket that had waited for no one—an appeal involving an emergency placement, a mandamus petition that felt like a cry for oxygen, a stack of fee petitions disguised as motions. I read. I wrote. I kept a picture Tyler drew on my desk of a bear wearing a bow tie. When attorneys tried to be charming, I let the law talk back.

My mother sent a letter two weeks later. It was handwritten on expensive paper, the kind that announces itself when you open the envelope. It said she was sorry. It said she didn’t know. It said she thought she was helping. It said she had always wondered why I worked so much and never thought to put curiosity in the same room as a phone call. I did not write back. There are apologies designed to relieve the sender, and there are apologies designed to repair the object. I could not be the object and the repair at the same time.

Marcus completed his classes. He showed up on time to the supervised visits. He asked questions in a way that suggested learning instead of loopholes. He stopped sending me articles about “shared parenting trends” and started sending pictures of Tyler’s drawings from his apartment—stick figures and crooked houses and one affable giraffe with fourteen legs. When the six months were up, the supervision lifted. We don’t text each other. We text about Tyler.

People imagine vindication feels like fireworks. It doesn’t. It feels like clear water. It feels like going to work and then going home. It feels like not meeting other people’s chaos with your own.

I stopped apologizing with my clothes. I still wear navy blazers because they’re practical and I like the way their buttons feel in my palm when I’ve had to listen longer than anyone else in the room. But I also wear a red scarf if I feel like it. When someone introduces me at a charity event with my title first, I say “Rebecca is fine,” and then I say what I do.

I started bringing Tyler to my office once a month on an afternoon when the docket is light and the clerks want a reason to smile. I let him sit in my chair when it’s empty and talk to the wooden owl on my bookshelf as if it were a person. I do not let him bang the gavel. In the closet behind the bookshelf, I keep a shoebox full of letters from women who have been told by someone—sometimes a husband, sometimes a mother—that they are not enough of whatever is required.

At night, when Tyler is asleep and the dishwasher hums and the city spreads itself into its evening map, I sit at my kitchen table with a glass of water and a legal pad and I add to a list I started the day before the hearing. At the top, in plain block letters, it says: Assumptions are not evidence. Witnesses are not always truth. Love is not leverage.

Part Two

If you’ve never seen a Chief Justice of a state supreme court take the stand in a family courtroom, I will save you the effort: it looks like a boundary people didn’t know existed being drawn in permanent ink. The story traveled faster than most truths manage to, mostly because it rearranged an old narrative: daughter dismissed by family turns out to be judge; mother scolds from the stand; Chief Justice stands up and says, “She’s been serving with distinction for eight years.” There is a reason writers iron that sentence into headlines.

But the headline is never the story. The story is the work. After the hearing, that work multiplied.

It multiplied in phone calls I started getting from legal aid clinics asking if I would come talk to teams about how to identify coercion dressed as testimony. It multiplied in the clerk’s office, where a stack of letters arrived in pale envelopes from mothers and grandmothers and a retired teacher in Knoxville who wrote, “I raised my daughters to shrink themselves. I hope you raise your son to stretch for others.”

And it multiplied in a quiet way in my own house, where Tyler’s questions hopped across the floor like sunlight does when it’s late afternoon and the blinds are half open.

“Mom, do judges ever make mistakes?” he asked, one Tuesday, face serious with the kind of worry children feel when they discover adults are human.

“All the time,” I said. “That’s why we write things down and let other judges read them. It’s why we listen to people longer than feels comfortable. It’s why we change our minds in public.”

“Did you make a mistake with Grandma?” he asked, in that way children swing one truth into another.

“I made a boundary,” I said. “Boundaries can look like mistakes to people who benefitted from not having them.”

He nodded as if I’d explained how rain works.

I wrote an opinion that winter that will likely follow me longer than any of the others. It was about a mother whose sister had convinced the court she was unfit based on letters written out of fear instead of facts. Reading the record made me feel the tilt of that day with my mother on the stand, like a catch in gravity you account for without letting it knock you off your feet. I wrote into the law itself what the Chief Justice said on that witness stand about me: that people’s roles are not guarantees of their truth. I wrote that courtroom oxygen must go to children first. I wrote that the adjective “unstable” can be a cudgel in the hands of those who dislike the way someone refuses to arrange their life around another person’s idea of comfort.

I did not cite my mother. I cited precedent, and then I wrote a sentence that made my clerk look at me with the sort of smile you save for when the law makes a human noise: “When love speaks for itself, the court listens; when love puts on a uniform to masquerade as evidence, the court takes that uniform back.”

If this were the kind of story where I called my mother and forgave her and we met for lunch and said “the past is the past,” some of you would feel better. If it were the kind of story where we never spoke again and she sent sad Christmas cards and I threw them away without opening them, some of you would feel justified.

What happened was neither.

Six months after the hearing, I ran into my mother outside a grocery store. She had a list. She always has a list. Lists make her feel temporarily immune to regret. She saw me and did the thing she did at my middle school concerts when she arrived late and didn’t want anyone to notice: the small, apologetic wave. We stood there like statues who had been told to improvise.

“I read your opinion,” she said, because she will die arranging data points into meaning. “The one about the mother and her sister.”

“I wrote it,” I said, because I will die naming things as they are.

“You’ve always been good with words,” she said. “I wish I had been kinder with mine.”

“I wish you had been curious,” I said. “Kindness without curiosity is just a performance.”

We stood there for another minute. She asked if she could see Tyler. I said yes. She asked if she could bring him to her house. I said no. The apology she’d mailed had been for a performance, not a repair. You earn visits the way you earn trust: slowly, honestly, without skipping steps. I told her we could start with coffee at the park. She nodded. For the first time in a long time, it felt like both of us were trying not to win.

There is a hallway on the second floor of the courthouse where portraits of former justices hang. They’re all framed in the same wood, in the same light, faces set in the same “I know you’ll reinvent my legacy” expression. When I was sworn in eight years ago, I walked that hallway with the quiet understanding that the law is older than anyone’s ego and younger than anyone’s certainty.

After the hearing, I started walking that hallway differently. I thought about the way titles can be armor and weapons and sometimes mirrors that reflect the person you hoped you were. I thought about how my son will one day be old enough to Google my name and find that headline about his grandmother testifying that I can “barely hold a job,” and I hoped the search results would also cough up the sentence the Chief Justice said in open court: “She’s been serving with distinction for eight years.” Both sentences will be true—one as an accusation, one as a correction. Tyler will learn that truth often arrives in pairs.

Sometime in spring, I walked into a courtroom to see another mother shrink before a father who had learned how to speak in the tone of a gentleman who does not raise his voice because the world rarely makes him. He told the judge she couldn’t “manage the schedule” and was “secretive” about her work—she cleaned offices at night so her son could have breakfast in the mornings—and that “grandma says” is good proof if you say it in the right voice.

I kept my face in the expression judges are given, but inside I felt every floor tilt again. We took evidence. We brought light. We wrote the word “hearsay” where it needed to go. We sent a boy home to the parent whose love leaves receipts.

I had lunch with Chief Justice Barrett one day in a diner fifty miles from the courthouse, the kind of place where nobody cares what your robe looks like as long as your coffee doesn’t go cold. He asked about Tyler. He asked if I’d considered writing a book. He asked—between bites of a sandwich he orders every Tuesday—how I was doing, and he asked it the way people inside our work rarely do, as if the answer might require two breaths instead of one.

“I learned something,” I said.

He raised one eyebrow, the way he does when he’s about to steal whatever you say and dress it up for a footnote.

“I learned that hiding your light doesn’t protect you,” I said. “It just makes it easier for people to underestimate you.”

He didn’t reach for his pen. He didn’t quote me back to myself. He just nodded.

On the anniversary of the hearing, I took Tyler to breakfast, then to the park, then to the library, and then we drove up to the mountains to sit in the small A-frame cabin that my grandmother bought when she’d saved enough to say yes to something she wanted. I told him a story about what she used to say when I was a child and frightened of thunderstorms.

“She’d count the seconds between the lightning and the thunder and tell me the storm was walking away,” I said.

Tyler looked through the window at a sky he will one day rearrange into new meanings. “What if it’s walking toward us?” he asked.

“Then we go inside,” I said. “We close the windows. We stay warm. And we do not mistake the noise for danger we can’t handle.”

He nodded as if I’d explained how courts work.

That night, after he fell asleep, I sat at the small kitchen table under the string lights my grandmother would have called “fancy” and wrote a letter I will put in a shoebox he can find when he is twenty: Dear Tyler, when love is loud and law is quiet, listen to both and then choose the one that keeps you whole.

I folded it next to the list I keep for myself—Assumptions are not evidence. Witnesses are not always truth. Love is not leverage.—and I added a fourth line, because even judges learn: What you hide to be humble can be used to call you small.

If you’re reading this because you saw a headline—because your feed served you a story about a mother called a failure by her own mother, and a Chief Justice who stood and said, She’s been…—I will leave you with a small, stubborn truth I have learned to count on:

Justice is not just what you serve. Sometimes it is what you claim for yourself. Not with a shout. With an envelope. With a witness who knows your work. With a sentence no one can undo because it is written by time and verified by the lives you’ve tried to take care of.

The rest is weather. The work is the map.

END!

News

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives. CH2

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives …

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load