SEAL Jokingly Asked For Her Rank, Until Her Reply Made the Entire Cafeteria Freeze

Part I — Dust, Heat, and a Question You Only Ask Once

The sun beat down on Forward Operating Base Rhino with a weight that turned every surface into a slow burn. Helicopters beat at the sky. The generators hummed their nameless song. Lieutenant Commander Sarah Glenn moved through the glare in khaki pants and a blue button-down that looked too gentle for Afghanistan, a small hardback notebook tucked against her ribs like a second heart. The pistol on her hip felt normal now. Three months will do that to you—it will make the strange useful and the useful sacred.

“Space was the easy part,” her father had told her when she was eleven and the world still fit in a NASA cafeteria. “It’s people that are the real challenge.” Colonel John Glenn, first American to orbit Earth, had made a map of the sky with his own hands and told his daughter to learn to read faces, not stars. She had. She’d done MIT because numbers kept you honest and then stunned everyone—especially the men who expected her to wear a flight suit—by choosing naval intelligence over NASA. “One Glenn in space is enough,” she’d said to the reporter with the polite smile, while the truth hummed unbeknownst beneath it: I want a frontier you can’t photograph from orbit.

In her notebook—a habit she’d never surrendered to digital convenience—sat three weeks of puzzle pieces. Satellite captures, HUMINT threads, hand-drawn arrows pointing from KORANGAL to SHEPHERD’S PASS, a circled compound on the map like the pupil of a black eye. She had led four night operations in-country, crawling into mountains with men who’d tried not to notice she could do the same things they could do. She spoke Pashto and Dari the way a person speaks languages they learned in kitchens, not classrooms. Today’s briefing carried a classification stamp that would lock most of the base out of the room.

The cafeteria gave up its air conditioning like a truce. It smelled like fries and floor cleaner and the bodies of people you’re responsible for. She could spot the SEALs the way you spot wolves—quiet, bearded, occupying space with the absence of apology. One of them—the last to enter—was a caricature of what the Navy recruits by accident and the movies on purpose: tall, shoulders that didn’t fit chairs, a gravity that pulled attention as easily as he carried trays. He called out across the room, “Any of you ladies save me a seat?” and his team laughed the way men laugh when they know they’re safe to.

Sarah set a bottle of water and an apple on a tray and chose a corner table. She didn’t belong to the room; that suited her. Intelligence gathering is a sport best played at the edges.

“Word is we’re heading into the mountains,” the tall one said around mashed potatoes. “Some spook’s got us tangoes to dance with.” His friends snorted. Someone made a joke about intel officers who never saw dirt under their nails. Sarah suppressed a smile and annotated a margin—insert here: trust you earn the minute they stop making jokes.

“Hey, Harvard,” the tall one called after a minute. She looked up because he wanted her to. “You State Department or something? You look lost.” His grin said it was a joke he knew he could survive.

“Just finishing some work before a meeting,” Sarah said, polite like a blade can be polite.

“What’s your rank if you don’t mind me asking?” he asked, sing-song and harmless, expecting—what did men like that expect? A contractor? A junior? A woman who would giggle and say she was just helping with the slides?

Sarah closed her folder. It was a decision. The room would open from here one way or the other. “Lieutenant Commander Sarah Glenn,” she said. “Naval Intelligence.” She slid her credentials across the table because paper speaks the dialect even cynics understand. “I’ll be briefing your team in thirty minutes on Operation Shadow Hawk.”

The name landed like a dropped tray. The lieutenant’s smile slipped. You could hear the cafeteria adjust itself. Conversations thinned. Heads turned. Someone at the condiment station closed their mouth around a word and swallowed it empty.

“Glenn?” he said, the way people say, Is it true.

“As in yes,” she said, because she got this question as often as she got her own coffee. “Colonel Glenn is my father.” She let that sit just long enough to satisfy the curiosity that would otherwise interrupt her briefing. Then she cut it free. “More relevantly, I’m the officer who’s been mapping movements in the Korangal for three months. I’m the one who put this together.” She rolled her sleeve to the elbow and showed them the scar. It still itched when the heat turned mean. “And I’m the reason Rahim Khan and his family got out of that village alive two weeks ago.”

The lieutenant’s face shifted through three things in the space of my father’s heartbeat: amusement, then caution, then something he hadn’t brought to a cafeteria since he’d been in a uniform without a beard—respect.

The doors swung open. Commander Jackson filled them without being theatrical. He saw her first because of course he did; good leaders know where the gravity is. “Lieutenant Commander,” he said with the minimal nod of men who have done crisp things together already. “I see you’ve met my team.”

“Just getting acquainted, Commander,” she said, stacking her materials into a neat pile that made geometry proud.

“Good,” he said. “Because in twelve hours, you’ll be accompanying us into the valley.”

A murmur ran through the team like wind through wire. Intel officers did not. Usually. You placed them in rooms and fed them coffee and let them fight maps instead of men. Sarah’s pulse accelerated the way a car hums when you want it to.

“May I speak with you privately?” she asked.

In the command center, the light was a different color. The world looked ghosted—thermal images and satellite overlay. Their primary extraction route, a meandering goat track down the southern ridge, glowed bad. Thirty heat signatures where yesterday there had been tree line. “They knew,” Sarah said. “Someone leaked.”

“Mission is still a go,” Jackson said. He looked at her like a man who wanted her to argue because he needed a better plan and didn’t have time to make it himself.

“With respect, sir, the route we filed this morning is suicide now.” She pointed to the north face. “We insert here.” He looked like a man who liked cables and didn’t trust rock. “It’s unwatched because it looks like a wall.”

“It is a wall,” he said.

“Not if you’ve climbed El Cap,” she said, and held his eyes steady enough for his calculus to finish. “I have. Twice.” Two summers ago, rope-cut hands, fingers singing, fear like a small bird you keep in your mouth until it becomes yours.

He took the beat he needed. “And exfil?”

“Shepherd’s Pass,” she said, tracing a narrow line that looked like it fit a goat and not six men and a woman with a backpack of fear. “It spits you onto a plateau we can get a bird into at dusk if we’re lucky or at dawn if we’re smart.”

“And in between?” he asked.

“We don’t get seen,” she said, and didn’t add, We don’t die.

“Be ready,” he said. “You’re coming.”

The lieutenant caught her at the door. “You climbed El Cap twice?” he said, too interested to hide it behind a joke.

“I didn’t say I topped out,” she said. “I said I climbed it twice.” He laughed. It sounded different than earlier—less like performance, more like relief.

By night, FOB Rhino was a collection of music without melody. As the rotors cut the darkness, Sarah thought of her father beyond the sky, Earth small and whole. She wondered if he was awake somewhere on the other side of the world or if he was sleeping with the knowledge that his daughter had chosen gravity and all its ruin and wonder.

They hit the mountain like a question. The face looked impossible. All the best work is. The rock ran the way quartz runs through granite—unexpected, a weakness you could use like a friend if you knew how. They climbed in pairs, the lieutenant—Reeves, she’d learned—close enough to make a joke and far enough to respect that hands are holy when they are full of work.

Halfway up, gunfire scattered sound below. Shouts in Pashto, flashlights knifing. “They’ve spotted us,” someone hissed in her ear.

“No,” Sarah said. Her eye to a scope. “Different team. Half a click southwest. They’re pinned.”

Jackson swore quietly. “Not our problem.”

Sarah looked at the valley and decided what her father would have said. He’d said courage is not the lack of fear. It’s what you do with fear sitting in your pocket like a stone. “I know where the intel is,” she said. “Let me go. Split the team. You peel Reeves with two to support that unit. You and two with me. I’ll get the hard drive. You save the men.”

He didn’t ask if she was sure. He asked, “Can you make it?”

“I can.”

“Do it.”

The split felt like tearing fabric. Reeves looked at her with something that wasn’t permission. They went the other way and sounded like they had been born to.

The compound was a stutter of empty. Lights left on, doors half-open like bait. Sarah’s equipment saw heat where a man would see nothing. “Two inside,” she whispered. “Right, then left. Basement east side, hidden door—brick loose under the second shelf.”

“How do you—” Wilson began.

“I was here,” she said, and they didn’t ask for the story because the story would have included a boy who had cried and men with guns who didn’t expect a woman to make the choice she made.

Jackson and Ortiz cleared with quiet violence. There is a moment in every room-clearing where everyone is excellent, and it is over, and you swallow three breaths to keep whatever you saw inside so you can use your hands for something besides shaking. Sarah pushed the shelf, kicked the bottom brick, slid the panel, and went down into a cold that had nothing to do with air. Names, dates, locations. Hard drives that hummed like crickets. She photographed, copied, burned to a stick she wore around her neck when she slept and to two others she taped under her wrists where no one ever thought to look.

“Got it,” she said. Her voice sounded calm. That is something training can do. It cannot make your hands stop wanting to tremble.

“Reeves?” Jackson asked into his mic.

“Extraction successful,” Reeves replied, voice breathless. “Martinez is hit. Status serious. Route home is hot.”

“Come to us,” Sarah said without waiting. “Bring them through the compound. We’ll pull them across our tracks. We’ll carry him between.”

“Your plan sucks,” Reeves said.

“You’re welcome,” she said.

They made a decision that day that no one would write in a file and everyone would keep in muscle: they saved their own and they still got the thing they came for. They moved like they were made for it. Twice Sarah shot in a way that made later impossible. Once she kicked a grenade into a place it became noise and not death. Once she said to an old man in Pashto, “Help us,” and he looked at her and saw his niece in her, someone had told her once, and opened a cellar like a secret.

They lay in the dirt of a floor that had never been meant for this and waited for a sound that meant hope—the distant kelp-slap of rotors beating a dusk into something useful. Martinez didn’t die. Reeves learned to say thank you without wanting to make it a joke. Jackson put his hand on Sarah’s shoulder exactly once and said, “It worked.”

At 02:08, Sarah’s intel pinged out of a cable in a base in Bagram and into a room in the States where men who had never sweated on a mountain made three phone calls and three attacks did not happen, and no one told the news because the best days’ headlines are the ones that don’t exist.

Back at Rhino, the cafeteria looked smaller. Reeves nodded at her like a man who had learned a language without knowing he’d been studying. Someone made room at a table and no one called her Harvard.

Jackson stood in the doorway. “What happened at Shepherd’s Pass,” he said, voice even, “doesn’t go in the report in any way that gets anyone in trouble.” The team looked at him, at her. “But it goes in the recommendation.” He handed her a folded paper that would become a medal if people who knew how to file things needed it to be. “Silver Star,” he said. “For an intel officer who can climb and shoot and make me do what I didn’t want to but needed to.”

She thought of her father looking down. He had seen Earth whole and small. She had seen it up close and broken and worth it. Both views seemed necessary. She stuck the recommendation in her notebook next to the drawing she’d made of a goat path that saved ten lives.

Outside, the sun climbed back into the sky as if it hadn’t left. She stepped into it and let herself feel the burn. She had to be at a desk in twenty minutes. Maps don’t read themselves.

Part II — Rooms Where Paper Matters

Forward Operating Base Rhino had rules that lived in binders and rules that lived in bones. The first kind would tell you who was allowed to be where and what they could say once they got there. The second kind would keep you alive. Sarah navigated both. She’d learned early that the men who made jokes about her were trying to survive something that killed the ones who didn’t laugh. She’d learned early that she could meet them in their language without giving up her own.

Her father wrote long emails on planes because retirement didn’t fit him well. He wrote like a man who had spent time in weightless rooms and knew the value of force. “I saw the map, kiddo,” he wrote after Jackson sent him the unredacted version of what she’d done (men who had flown an orbit once traded favors like old CIA buddies). “You made good choices. That’s all we get to do.”

She kept the scar under her sleeve so the men in the chow hall didn’t mistake it for a story she wanted to lead with. She wrote the real story down on paper because men who turned words into bullets could not take paper from her.

Bagram issued the award in a cramped ceremony that smelled like cleaning fluid and confusion. Jackson pinned the star on the pocket of a uniform she only wore to satisfy the same category of men who needed pins to understand what had occurred. Reeves shook her hand and didn’t try to make it a joke. The base commander made a speech about interagency cooperation that made Sarah want to draw a diagram on his face to help him understand the geometry of trust.

The plaque went in a drawer. She had another briefing in thirty. You don’t talk about yourself too long in a room where plots still need killing.

The email from Langley appeared while she was checking a satellite path. It was short because people who actually risk their lives learned to write short. Nice work. We owe you one. It had a map attached with three red lines crossed out. The note below it said, In another timeline, mothers are crying. Thank you for this one.

She slept three hours in a dark that had nothing to do with light. When she woke, she checked her notebook and found she’d written next to the goat path a line her father had written under a photo of Earth. “Look again.”

Part III — The Second Question You Only Ask Once

The mission changed the cafeteria because people change cafeterias. The next week, a new batch of special operators rotated through, all of them looking the same until they opened their mouths. A captain with eyes like a storm and humor like a gun called out from the line, “Hey, Harvard. Where do you want us to sit?”

“Next to the exit,” she said without looking up. “You’ll want to leave fast to make it to the briefing.”

He laughed the right laugh. He had learned.

Reeves took to carrying an extra Sierra cup. He handed it to her once without a word when the coffee line was ten deep and she needed to still be at a map in three minutes. She took it. These small things matter. They are architectural details in a building that people think only exists because load-bearing beams do.

The Afghan elder from the village sent a boy with a note in Pashto that said, We are good this week and a jar of preserve that tasted like figs and sugar and secrets. She sent back a thank you and two packs of batteries and the knowledge that she would owe him one forever. She kept a list of these in pocket three of her notebook. Debts owed. You want to keep these short.

The mountains kept trying to kill them and the men kept letting laughter live in the places it was allowed to. The women—because there were more women now in rooms where women were supposedly not useful—learned to let themselves be language more than body. “You don’t have to prove your rank,” one whispered to Sarah in a bathroom, the kind of place everything important gets said. “You already did.” They left the bathroom and did not hold hands because some things you do for self are more sacred when no one is watching.

Sarah thought sometimes about Huggy’s diner in Ohio, the place her father took her for pancakes before the press wanted to turn him into a statue. She thought about the way the waitress called him “honey” and the way he turned his face to her with the same equal gravity he gave congressmen. He’d shown her how to “sir” the right people and ignore the rest like wallpaper. She kept a list in the back of her book called People Who Are Real.

Jackson requisitioned a climber’s kit because he had learned. Reeves stopped calling her Harvard and started calling her Glenn and then Sarah when it was just the two of them and the air was not heavy with other men’s opinions.

“Your father ever see you like this?” Reeves asked once on a perimeter, scanning a sky that looked harmless but never is.

“He sees me enough,” she said. “He would hate the dust.”

“He ate dust,” Reeves said.

“Space dust,” she said.

Reeves laughed the grudging laugh of a man who had just learned he wasn’t going to win. “Fair.”

Part IV — Shepherd’s Pass, Again

You think you’ll get one Shepherd’s Pass per deployment. You are always wrong. Two weeks after the climb, word came through a channel Sarah didn’t like to use—older, lazier, more prone to leak. A high-value target making a move. A convoy. Coordinates that lined up with a map she had drawn two months back and labeled “if they’re smart, here.” The team gathered in the command tent and she walked them through the geometry. Reeves asked one question at the end that told her he had been listening. Jackson didn’t ask any because he had learned the trick of trusting the right voice the first time he heard it.

They launched into a wind that felt like someone arguing with God. The black hum of a bird chewing sky. Sarah’s legs knew the pain before they were there to feel it. The mountain came up under them again with the same jaw. It hurt less because they had already made it say yes once.

They found a place to put the bird before dawn, slid into rock like a secret, and waited for the convoy. The men Sarah had mapped—men whose names the newspapers would not know and whose mothers would pretend not to read the right papers—appeared where she had thought they would. The team moved the way trained bodies move. She watched faces, not angles, and turned fear into a list of things to do. It is a survival skill to make every emotion pay rent.

A shot. A ricochet. Reeves swore. The air filled with the kind of math that gets you killed if you do it wrong. Sarah saw a boy with a rocket launcher teach himself to be a man in the worst way and fixed it with a single bullet and a prayer she didn’t believe in. Jackson took three steps forward when he had only meant to take two and the difference kept him alive.

When it was finished and there were more Americans in the world than there would have been, she found a place to sit and drink water and listen to her heart beat like a drum. Reeves handed her the Sierra cup without looking at her and she took it like it meant more than it did because sometimes you are allowed to.

They waited for the bird. She rewrote two lines in her notebook because they hadn’t been true enough.

Back at base, the men from the special forces unit from last week—faces new and already old—brought a pie to the Intel tent. It tasted like fruit and gratitude. They told jokes you can only tell in rooms that have seen you bleed. Sarah laughed and let herself be part of it. She kept her sleeve rolled down because some scars are for the people who have earned them.

Part V — What Freezes Cafeterias

The first time someone called her ma’am in the cafeteria without saying it like it was a mistake, the spoon clattered against the tray and nobody looked up. It was unremarkable. That is how change sticks.

A new SEAL team rotated in. They looked at her with the curiosity of men who had heard stories they did not trust. The lieutenant—new—called out, “Hey, Harvard,” and Reeves said, quietly, without making a scene, “Don’t,” and the man didn’t know why he listened, but he did. The room kept doing whatever cafeteria rooms are supposed to do—feed bodies and rumors and the dull hum of waiting.

The base commander walked past her in the hall and said, “Commander Glenn,” and then, remembering himself, “Lieutenant Commander,” and she said, “Either is fine,” and smiled because it cost her nothing and bought him three hours of telling other men the right way to say the wrong thing.

She called her father on a Sunday and told him the story of a young man in a cafeteria who had asked her rank and then learned it. He laughed the laugh of a man who had been asked questions he was never supposed to answer. “People will always test your weight,” he said. “Just remember, you are load-bearing.”

“Thanks, Dad,” she said, and then, because she could, “I know.”

Ben the nurse from the ER wrote the kind of email that only people who clean up after heroes write: We’re good. Coffee on me when you get back. She wrote back: I prefer tea now. He replied with a middle finger and a smiley face. She put him on the list of people who are real.

On the last night before they rotated home—because you always rotate home, even when home is a memory of a kitchen and a hand on a forehead—they gathered in the cafeteria because it had become a church. Cakes appeared in ways Sarah chose not to ask about. Someone smuggled in good coffee from a supply sergeant who owed him one. Jackson said nothing meaningful because he wasn’t built like that. Reeves lifted a cup and said, “To the person who made us climb a wall that wasn’t a wall,” and the room said, “To Glenn,” and the word froze there and then moved again, and that is the important part.

Back in the States, Sarah would walk past cafeterias too quiet to trust and think of this one, and the mountains, and a goat path, and a boy she had chosen not to shoot because the choice had not been necessary. She would think of a cafeteria freezing not because men were about to make a woman small, but because they finally realized she had been large the whole time and they had not bothered to look.

She flew home. She put her notebook on a shelf next to a photo of her father looking at Earth the way he had looked at her at a science fair in fifth grade, like he had been given a gift he would spend the rest of his life trying to be worthy of. She slept in a bed that did not shake. She woke to a sky her father had once circled and a world that had gotten three attacks less because she had answered a question in a cafeteria with the truth.

In a year, she would write a letter that would change a policy that would put more women into rooms where they had always belonged. She would teach a class to a dozen men who would learn how to use maps to listen, not to tell. She would watch Reeves get married to a person who found his jokes endearing and his fear manageable. She would visit Jackson’s wife in a hospital and hold a baby named after a mountain.

But that’s later. For now, the ending that matters is this: a woman walked into a cafeteria and someone asked her rank like a joke. She answered with a name, a job, and a scar. A room changed. A mission changed. Three lines on a map were crossed out. Somewhere, a mother slept.

When the base sent her home, she packed her star at the bottom of a drawer because she did not need it to remind herself who she was. She kept the Sierra cup on a shelf because some debts you honor with objects that know what you had to do.

She stepped onto a tarmac under a sky that had nothing to say and said to herself, “Do the next good thing,” because life is boring in its demands when it is not trying to kill you. Then she went inside and did it.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

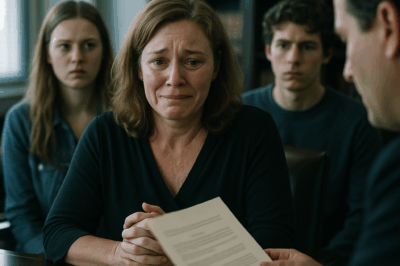

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will Part One I never thought I’d…

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night Part One…

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement Part One I never…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then… …

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead Part I — The Test Shot…

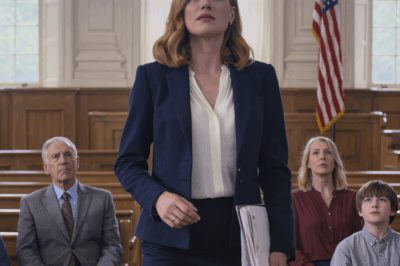

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything Part 1: The…

End of content

No more pages to load