Rushing to My Fiancé’s Mansion, I Defended a Helpless Stranger… and What I Discovered Shocked Me

Part One

I didn’t register the cold until it crawled past the fabric of my blouse and touched skin. The rain had started as a whisper at dinner and turned into a verdict by the time I reached the gate: fat, impatient drops that flattened the boxwoods and slicked the marble steps of the Grants’ estate until the whole façade blurred. By the time I hit the sidewalk, hair plastered to my cheekbones, heels squeaking, breath fogging, I wasn’t walking so much as evacuating. I only meant to get to the bus stop. Instead, my brain kept replaying the evening, syllable by syllable, like a cruel subtitle I couldn’t turn off.

Dinner had meant everything. For months, Tyler had dodged the subject of his family with a practiced shrug, a “they’re private” that was supposed to sound protective but had always felt like a velvet rope. Then last week, standing in my tiny kitchen with his tie undone and an easy grin, he’d said, “It’s time you meet them, Nat. You’re important to me.” Those words hovered like lanterns in my head while I stitched a blush blouse from a bolt of discounted silk, while I re-hemmed my navy dress because my best pair of heels would need all the help they could get, while I told my mother not to worry and set my alarm fifteen minutes early to curl my hair.

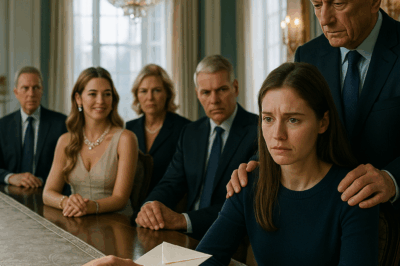

The Grants’ mansion looked like something borrowed from a magazine—too clean, too quiet, too curated even for the rain. A chandelier the size of my living room flickered above a foyer that felt like it might echo forever. The butler opened the door before I reached for the bell, murmured “Miss Cooper” without surprise, and ushered me across marble so polished I was afraid my thrift store soles would squeal apologies.

Tyler descended the staircase with that smile, and I believed in him for one more minute. Long enough to taste the promise under my ribs: he is going to take my hand when they ask where I went to school; he is going to say he loves that I make things with my hands; he is going to mention my mother by name and call my apartment cozy and say money is a tool, not a religion.

His parents sat at a table long enough to host a wedding if the vows had been about money. His father shook my hand with a grip that communicated strength, control, and a thin, polite boredom. His mother was all cream silk and pearls and eyes that walked up and down me like a scanner trying to locate the barcode.

“Your home is beautiful,” I said, thereby rehearsing the role of grateful outsider. My dress felt suddenly too soft in a room of edges.

“Thank you,” his mother said without inflection. “We do our best.”

The questions began before I could breathe. Not the curious kind that move toward you but the litmus test kind, dressed up as conversation: Where did I go to school? (A vocational college on the edge of Des Moines.) Why not a four-year university? (Because rent, because my mother’s heart, because I need to work with my hands to feel alive.) Had I considered a real career? (I altered wedding gowns while women cried and then laughed; I had watched shoulders drop an inch and a half when someone finally felt like themselves. What is real if not that?) Did we rent or own? (Rent. Two bedrooms. One sewing machine that never gets a day off.)

With every answer, something in their faces clicked and closed. Tyler swirled his water glass and watched the condensation. When his mother said “How admirable,” it did not sound like a compliment so much as a condolence.

By dessert—a lemon tart I didn’t touch—my throat burned from forcing kindness to stay where it belonged. I folded my napkin, set it on crystal, and smiled as if the expression would hold me together. “Thank you for dinner. I should go.”

His mother’s lips curved into that dangerous shape again. “Of course. It was… enlightening to meet you.”

I waited for him to stand. To say anything. He adjusted his cufflink.

Outside, the rain decided it had waited long enough and came down in a way that made traffic lights smear into long, red trembling lines. I wrapped my arms around myself to keep from coming apart. The bus pulled up hissing, and I stood, dripping, clutching the pole, trying not to cry because I didn’t have the luxury of sobbing to strangers when my mother’s heart noticed every wobble of mine.

I’d taken the same route across town a hundred times for fittings and grocery runs and thrift store miracles. The bus driver tonight was new, his voice patient in the way of a person who has decided to be kind even when no one is watching. The bus was almost empty, which is the only reason I heard the argument before the doors finished folding.

“Ma’am,” the driver said softly. “I’m sorry, but I can’t let you ride without fare.”

A woman stood at the front of the bus, her tan coat buttoned unevenly, her knit hat damp, hands gripping a canvas bag like it held a life. “Please,” she said, her voice trembling but not whiny. “My grandson is at Mercy General. He had an accident. I’ll bring you the money tomorrow. I swear.”

People pretended to be very interested in nothing. My feet moved before my brain did. “Here,” I said, fishing out a crumpled bill and sliding it toward the fare box. “Two rides.”

The driver shot me a look that held thank you and I’m not supposed to let you do that and God bless you in the same glance. The woman turned to me with the startle of someone who has stopped expecting help. “No, sweetheart. I can’t—”

“It’s fine,” I said. “Sit. Mercy General, right?”

Her shoulders dropped, the way shoulders do when a weight unhooks. “Mercy General, yes.” She squeezed my hand before shuffling to the weathered seat across from mine. For a few blocks, she clutched the edge of the vinyl and stared at the patter on the windows, gathering dignity with both hands.

“I’m Janette,” she said at last. “Janette Miller.”

“Natalie,” I replied. “Natalie Cooper.”

She nodded as if filing it under kindness happens. “Natalie,” she said, tasting the syllables. “You’ve got a good heart. The world forgets that sometimes. It’s good to be reminded.”

Three stops later she stood, tightened her hand on the old bag, and turned to me again. “I’ll remember this,” she said, not like a phrase but like a vow. I smiled because it was the only thing I could think to give. I thought that would be the end of her part in my story.

It wasn’t.

My mother had always said love’s first job is to build a room inside your life, not to renovate you. She’d also taught me that some people don’t know what to do with the room you made for them. They leave their shoes in the wrong place. They take the art off the walls and hang their own. They never ask for a key. I knew this in the blood-and-bone way you know things when your father leaves before you are old enough to form a memory.

Mom and I had built our life on a budget that required creativity. That’s how the sewing machine came to sit like a resident at the little desk by the window, the old Singer rattling its way through prom dresses and bridesmaid alterations and one glorious gown I made for a woman named Ariel who cried when she saw her own reflection and then laughed because she hadn’t expected to.

Mom had a heart that misbehaved and a laugh that refused to, and that meant I learned to fold laundry when other kids were still riding bikes after dark. When her cardiologist said the words “long-term management,” I learned what refills cost and which evening buses were least likely to make me late to wash her hair and make tea. It didn’t feel like sacrifice. It felt like the only math that made sense: she had given me life; I made sure hers was less heavy.

Which is why, after the Grants, I knelt on the bathmat and cried quietly with the water turned too hot and then stood up and wiped mascara off with toilet paper and smiled in the bathroom mirror until my face believed me. When Mom called from her bedroom—“Nat, is that you?”—I wrapped the towel tighter and said, “Yeah, Mom. Pouring out there,” and slid into bed with damp hair and a heart that finally admitted what it had known all along: I wanted to belong more than I wanted him.

Some endings announce themselves. Others sneak up and sit beside you while you’re threading a needle.

The morning after the rain, I made strong coffee and watched the weather pretend blue again. I’d just set a zipper when Mom’s breath caught. Not dramatically. Not movie style. The way a person does when pain makes a cameo and then decides to stay. “Just dizzy,” she said, waving me off like a fly, but her fingers pressed hard on her sternum.

We were in Mercy General by three, and her cardiologist was a kind man who looked like he had worn worry as a second shirt through two years of a pandemic. He said the medications were losing their argument. He said the word surgery like it was both hope and a cliff. He said “six weeks” and “sooner if possible.” He said a number for the cost that made the world tilt just enough that I leaned into his desk and said, “Is there a payment plan?” and he said “there are programs” and I made the calls and left the voicemails and listened to strangers say “we’re not taking new adult cases” and “this just isn’t the kind of story donors open their wallets for” and “if you had young children” and nodded into a phone because I didn’t trust what I would say if I used my voice.

It was four o’clock when I broke a promise to myself and dialed Tyler. He answered like he was already bored. When I told him, he paused just long enough to make me think a human might live under his expensive shirt. Then he chuckled gently like a teacher giving a sympathetic D. “Nat, come on,” he said. “I knew something like this would happen. My mom literally warned me.”

“I’m not asking for me,” I said, every muscle in my jaw a tightrope. “It’s my mother’s life.”

“I’m not a bank,” he said. “Don’t call me again.”

I put the phone down very carefully like it might be made of bone, then stepped outside into the strip of hospital concrete where people go to either cry or smoke or both. I sat on a bench and stared at the crack shaped like a question mark until the world spun less.

“Sweetheart, Natalie—” someone said, and I looked up and the world arranged itself into a person I knew.

“Mrs. Miller,” I breathed, and tried to wipe my face.

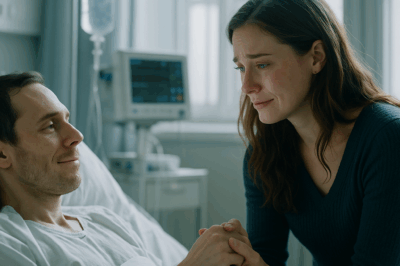

She didn’t make a fuss. She just sat beside me like she had paid rent to sit beside hurting people most of her life. When I told her about Mom, she patted my hand the way my grandmother would have if I’d had one and then called to a tall young man who was carrying two cups of coffee on a cardboard tray and a bouquet crowded into a hospital gift shop vase.

“This is the young woman I told you about,” she said. “The one who helped me get to Ben the day he woke up.”

Ben smiled a careful, kind smile. “Tell me what you need.”

I tried to say no. It’s dangerous how easily pride can be mistaken for strength. But I said the number anyway because sometimes the only strong thing is telling the truth. He didn’t blink. “Okay,” he said. “We’ll take care of it.”

“Ben,” I protested. “You don’t even know me.”

“I know my grandma,” he said, and shrugged in a way that made decency look unremarkable. “And I know what a hospital hallway does to the legs. Call it a favor I owe the universe.”

By the end of the second day, the billing office had stopped speaking to me like I was a problem and started speaking to me like I was a person again. They had a donor; they had authorization; they would schedule the surgery. When they asked my relationship to the benefactor, I said “friend,” and it was not a lie.

Mom squeezed my fingers on the morning of the operation and said, “Don’t let this scare you. Pain can become a door sometimes.” It sounded like something she’d cross-stitched onto the kitchen wall, but this time she meant it exactly.

The surgery took six hours. I learned the floor tiles around the waiting room by sight. Ben and Mrs. Miller stayed, delivering coffee at precise intervals and stories about the grandson who loved to skateboard off the shed roof while his grandmother yelled, then laughed. When the surgeon finally came out, he had a smile he’d been saving. “It went perfectly,” he said. “She’ll be very tired, and she will need you both, but she will live.”

I sat down and cried like I was emptying the rain barrel after a drought.

Tyler texted me the next day: Hope your interviews went well. We should talk. I stared at the screen long enough for it to feel silly and then typed: I’m at the hospital. We’re fine without you. He didn’t reply. He didn’t come. It was as morally clarifying as a cold front.

Recovery is chores in slow motion. It’s counting pills and counting steps. It’s trying to keep a woman who once scolded you for running indoors from getting up to do the dishes. It’s watching color come back to a face you had memorized in gray. It reaches into every room of your house and rearranges the furniture until you can walk in the dark without stubbing your toe.

Ben didn’t vanish after the bill was paid. He came by with flowers for my mother and legal pads for me. He sat at the kitchen table and drew a rectangle with “Cooper Bridal” at the top and then asked, “All right, Natalie. Where do you want the door? What will the floors look like? What will the first bride say when she sees herself?” He meant “What do you dream?” and he refused to let me dodge.

“It’s silly,” I said, because it felt smaller than the things that had almost killed us.

“It’s holy,” he said.

I told him about the women who cried when a hem allowed them to dance. I told him about sleeves that made arms look like they belonged to the body God gave them. I told him how satin and lace could be tools for mercy if your eyes were kind. He grinned like he’d just bought stock in hope.

“We’ll find a place,” he said. “I know a realtor who owes me a favor. I know a couple of investors who like returns that aren’t just money. And you already know a supplier because you’ve been their favorite person for five years.”

“What do I owe you if we do this?” I asked, because I had learned to ask what love cost.

“A good cup of coffee when you get the keys,” he said. “And two dresses a year at a steep family discount.”

We shook on it right there over a stack of discharge instructions.

Nine months later, my mother cut the ribbon on a little storefront with a bell that tinkled like it was blushing. People brought lavender and cookies. Mrs. Miller cried; Ben pretended he didn’t. The old Singer sat in the window like a patron saint, and the new machines hummed in the back like a chorus. The first bride we welcomed stood in front of the mirror, closed her eyes, and said, “I don’t recognize myself,” and then she opened them and said, “Oh,” and then she cried in the way that is about relief, not sadness, because she recognized herself after all.

Some evenings, when the last client has gone and the pins are all back in their cushion and the fabric smells dust-sweet and the streetlights smear the front glass, I sit at the little round table in the back and drink tea with my mother and listen to the bell and think about how a life refits itself.

Sometimes on my drive home, I take the long way and pass the Grants’ mansion. It still glows like a magazine. The same water still rises and falls in the fountain. Someone else walks through the front door with a perfect coat and a practiced smile. I choose not to hate her; I choose to be glad I didn’t spend my life being polite to people who mistook cruelty for taste.

Once, a month after my mother could climb the stairs without pausing, I saw Tyler at the farmer’s market with a woman whose name I didn’t know. He had a stubble he would have trimmed for me. We made eye contact and he opened his mouth to say the first words of an apology that would never become a sentence. I smiled the way strangers do when they pass in a crosswalk and kept walking. It felt like putting a heavy thing down.

Part Two

My mother healed into her old fastidiousness but kept the softness the scare had given her. She folded napkins into swans. She called Mrs. Miller twice a week to ask after Ben. She took up watering the shop plants with a seriousness normally reserved for weather. “You rescued me,” she told him once, half-joking. “We can at least keep geraniums alive in gratitude.”

Ben laughed, the quiet kind of laugh that looks down, then up. He never mentioned what he’d paid. He did, however, argue with me over leases and insisted we pass on a cheaper space whose back room smelled wrong. “You don’t put silk near a wall that smells like mildew,” he said, and I realized he’d been listening better than I thought.

“Why are you doing all this?” I asked one night when the shop was tired and the moon was full and he’d stayed to fix the bell that had started catching on humid days.

He shrugged. “Because when I broke my leg skating off the shed and promised my grandmother I’d never be clever again, she went into debt to buy me a better board when I got better.” He grinned. “She refuses to let the world turn me cynical. So this is me staying un-cynical.”

We kept it simple. He brought flowers and advice; I made coffee and lists. We took long walks that never once pretended to be dates. We built a friendship the way you build a dress—fitted, adjusted, stitched from the inside before anything fancy showed on the outside.

The shop gathered people. Not by advertising, though the sign Lily painted in her careful letters didn’t hurt. Not by undercutting price, though I once hemmed a skirt for free because the woman said, “I need to look strong in court tomorrow,” and I recognized the tremble in her mouth. We gathered people because the mirror in our fitting room didn’t lie and we didn’t either. We told the truth gently. We let tears be part of the process. We put bustles on without fussing. We sewed extra hooks for women whose bodies didn’t match the neat categories sewn into factory tags.

Women told their friends. Their friends brought their mothers and sisters. A local blogger wrote that we made clothes “for the moment and the person,” and I cried in my stockroom because that was the whole mission sewn into ten words.

A woman named Ruth came in one morning with a thrifted dress that had belonged to her grandmother. “It’s the only thing I have of her,” she said, stroking the faded lace like it was skin. “I want to wear it when I get my IVF news. I know that’s silly.”

I didn’t say it wasn’t silly. I pressed the darts flatter. I picked out stitches so carefully my shoulders ached. When she put it on a week later, the lace laid itself down on her shoulders like a blessing. She looked at herself and steadied. “I feel like me and like all the women who loved me,” she whispered. “And I think that’s going to have to be enough.”

I shipped her a silk ribbon the day she texted me a photo of a sonogram.

Another time, when the store was quiet and the light slanted just so, an older woman came in with a boy of maybe nine and said, “He wants a cape.” The boy’s hair stuck up and his glasses were smudged and he looked like the okay-ness of the world depended on what I’d say. “Of course he does,” I said. “So do I.” We made a cape. He spun in it until he fell down laughing, then stood and said, very solemnly, “This makes me feel like the good guy.”

Sometimes goodness requires a costume. Sometimes it requires a surgeon. Often it requires strangers becoming family.

The day I signed papers with the state naming me my mother’s medical proxy, we went out for pancakes. The waitress asked if it was a special occasion and my mother said yes without explaining. “Everything is special if you write it down,” she told me later, and showed me the list in her purse. Top item: “Wake up.”

On a Tuesday in late October, I found a plain envelope slid under the shop door with my name handwritten in blocky letters. Inside, there were two wedding invitations. The first was for a reception at a vineyard I’d only seen in magazines, names in gold foil, the couple’s smiles perfect like they practiced. Tyler’s. The second had a handwritten note paper-clipped to it: Can you make me brave? Love, Lila. The bride was a school teacher who’d saved pictures of my dresses for months before finally coming in. “I just need to feel like the best version of me,” she said. I sketched a neckline and she said, “That’s exactly where the confidence lives.”

I mailed the first invitation back with “regrets” checked and nothing else. I folded the second into my schedule and wrote “bravery appointment” on that day’s page. Lila walked down the aisle in silk that caught the light and sent it back politely to the sky. Tyler got married without me knowing if he flinched when the officiant said “honor,” but it didn’t matter. I had learned to stop writing myself into the story other people told about me.

In December, a girl named Paige came in with a teacher from her school. “She applied for an internship,” the teacher said. “She loves fashion. She loves the part where you pin and fix and make something work.” Paige stood there holding her sketchbook like a life preserver. Her drawing hand had calluses. “Do you take apprentices?” the teacher asked.

“I do now,” I said, and meant it. Watching Paige thread a needle with her head close to the desk light made something in me settle—the knowledge that someone had once made space for me, however indirectly, and that the only way to honor that was to make space for someone else.

We let her hem without panicking. We let her design a veil and told her where the seams needed to hide. On her last day, she left a note in my drawer: Thank you for making the world feel like a room I could walk into.

That winter, when the wind made the shop windows sing, Ben took me to look at an old warehouse two blocks away. “We could move in a year,” he said, hands in his coat pockets, breath fogging. “Add a classroom. Do workshops for girls who think a needle isn’t theirs to touch.” He looked at me sideways. “That’s your face. The one you get when you’ve already arranged all the furniture in your head.”

I had, of course. The long tables. The light. The whiteboard where courage would be written in marker. My mother would come and tell them about lists and waking up. Mrs. Miller would demonstrate how a seam ripper is a therapy tool. Ben would paint the shelves. I’d cry and pretend not to. I nodded and said “maybe,” because I’d learned to treasure the quiet between an idea and its announcement.

In February, Mrs. Miller slipped on ice outside her apartment and called me from the ambulance rather than Ben because “he’ll worry more awful if he hears it from me.” I met her at Mercy General and refused to let anyone move her until a nurse in real shoes came to do it. She had a sprain and a bruise that would bloom into the shape of Nebraska and a dozen jokes about how she’d become expensive in her old age. “I didn’t pay you back for that bus fare, you know,” she said, grinning at me from her hospital bed.

“You did,” I said. “With compound interest.”

On the first warm day of spring, we propped the shop door open and Lily set a pot of lavender on the step and my mother put a sign in the window that said, Love is work. We can help. Ben came by with sandwiches and a look on his face like he wanted to say something he wasn’t sure I’d want to hear. “I know a word,” he said finally, very seriously. “It starts with L.”

“Lease?” I lied.

“Later,” he said, and I loved him for defining love as the thing you can say gently without forcing it into the world too soon.

We took a walk down by the river that felt like a new garment—same body in a different fit. He told me about a summer when all the water dried up and his grandmother hauled buckets three blocks for tulips. “She said you have to water what you want to keep,” he said, not looking at me. “I’ve been trying to do that. I’m not always sure how.”

“It looks like showing up,” I said. “You’re very good at that.”

He kissed me under a streetlight with cracks in its base and the whole world hummed.

At the end of that year, after six brides sent me photos of laughter and three grandmothers sent me thank you cards with ink smudges from tears and one little boy came in wearing the cape I made him to tell me he “defeated a very terrible dragon in the backyard,” a letter came to the shop addressed to Owner, Cooper Bridal. It was from Mercy General. I assumed a bill had boomeranged; I tensed on instinct. Inside was a note and a list.

The note was from the billing manager. Dear Ms. Cooper, it said. Mr. Miller asked that we share this with you. He has established a fund in his grandmother’s name to cover “the impossible” cases—those that fall between programs, those that get turned away because they are boring and heartbreaking instead of headline-worthy. The first three were approved this week. He says you will know who they are. Thank you for reminding us that hospitals are about people.

I sat on the floor behind the counter and cried, the ugly kind, while my mother locked the door and put the kettle on. “I told you,” she said, handing me a tissue. “Pain becomes a door. Sometimes you get to hold it open for other people.”

I keep the bus fare receipt in my jewelry box, folded and fragile. It wasn’t a receipt, really—just a memory printed by a machine onto cheap paper that faded almost to nothing. Sometimes at the end of a long day, I take it out and hold it to the light until the faint numbers appear and I remember that everything started with saying yes in a small way when no one would have blamed me for saying no.

One weekend in May, Tyler and his new wife wandered into the shop because fate has a sense of humor and no respect for personal boundaries. I was pinning a hem and only looked up when the bell rang a second time because they couldn’t find a pen to sign the guest book. He froze two steps into the room like he’d walked into church and the stained glass had recognized him. His wife was lovely in the way women are when they’re trying too hard not to be. He said my name like you might say the name of a street you used to live on.

I smiled my shopkeeper smile. “Can I help you pick a veil?” I asked. His wife said, “We’re just looking,” the way people say when they won’t buy anything but want to try on stories.

They walked around slowly, touching lace the way you touch the edge of a life you didn’t choose. He stopped in front of the old Singer in the window and ran a finger along the decals the way you run your finger along a scar. Then he nodded to me, and I nodded back, and then the bell rang for someone who needed something and they were gone.

I went into the back and leaned against the dryer while my mother said nothing and handed me a square of chocolate. “You did good,” she said, as if I’d simply sewn a straight line. “You didn’t let an old bruise pull you down.”

“No,” I said. “I let it teach me where not to sit.”

On a summer evening when the sky turned the exact color of the fabric I’d kept for the dress I promised myself I would make if I ever learned to be kind to myself, we closed early and drove to a small park where a band played badly and children ran in circles and no one wore shoes that clacked. Mrs. Miller brought potato salad. Ben brought a bottle of something and enough paper cups to get us arrested. My mother brought a quilt that had outlived three couches and a divorce. I brought the feeling that I was exactly where I was supposed to be.

Ben kissed my temple and said, “We should buy that warehouse before someone puts an auto parts store in it,” and I said, “Fine,” and he looked at me like I’d reopened the word later and filled it with now. We made plans about paint colors and scholarships and summer camps for girls whose hands needed a job. We wrote the words Open Studio on a napkin and tucked it into my pocket like a promise.

On the way home, I detoured past the bus stop without thinking and stood for a minute under the streetlight where I had once handed a stranger a crumpled bill. The tinny hum of the city wrapped around me. It was not a remarkable intersection. It did not know it had been holy. I pressed my palm to the pole the way people press palms to old trees and said thank you out loud to no one. Then I walked home.

The thing about a life is you can design it. You don’t get to pick all the fabric. You don’t control the weather. Some seams will need ripping and resewing until the stitches lie flat. People you thought would come with you won’t. People you never expected will carry you across a hallway that smells like antiseptic and fear.

In the window of the shop there’s a sign Lily painted in careful brushstrokes. It says, We do alterations on gowns and expectations. Some days I think that’s all I ever wanted to do: hem a dress so a woman can breathe, and then hem a story so she does.

If you had told me a year ago that my fiancé’s silence at a long table would lead me to a bus where an old woman would introduce me to a young man who would save my mother’s life, and that in the space left by all that loss my own life would bloom until strangers clapped for it, I would have said that’s not how stories work.

But sometimes they do.

Sometimes you hurry toward a mansion and defend a stranger and leave humiliated and discover that the shock life has prepared for you isn’t cruelty. It’s kindness coming back with interest. It is the realization—damp and shivering and very alive—that the room you built inside your life is big enough now to invite other people in.

And then you open the door.

END!

News

One Small Request—Pretend to Be His Fiancée—But the Ending Brought Me to Tears… CH2

One Small Request—Pretend to Be His Fiancée—But the Ending Brought Me to Tears… Part One The dog trembled in…

My husband hit me after his mother spoke, but what he saw next shattered him completely… CH2

My husband hit me after his mother spoke, but what he saw next shattered him completely… Part One It…

My Parents Told My 7-Year-Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off. CH2

My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off Part…

My parents gave $10 million to my sister and told me to earn my own money! then grandpa gave me…

My parents gave $10 million to my sister and told me to earn my own money! then grandpa gave me……

I Tested My Husband by Saying “I Got Fired!” — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything. CH2

I Tested My Husband by Saying “I Got Fired!” — But What I Overheard Next Changed Everything Part One…

I was fired in front of the whole office. Then the janitor handed me a key and… ch2

I was fired in front of the whole office. Then the janitor handed me a key and… The rain started…

End of content

No more pages to load