Pregnant And Broken, I Returned To My Grandfather’s House. Just Yesterday, I Was Soon To Get Married

Part One

I always thought rock bottom would announce itself with sirens or screaming, maybe even a dramatic thunderstorm. Turns out, it can arrive in absolute quiet—just a cold November wind cutting through broken window frames in a house I hadn’t stepped inside since I was seventeen.

The place was exactly as I remembered, only worse. Faded wallpaper slumped off the walls like wet paper towels. The old wooden floors sighed beneath every step as if the house were tired of holding itself together. I set my overstuffed duffel on a rusting metal chair that groaned out a warning, then crossed to the tin stove my grandfather had insisted on keeping even after everyone else moved to electric.

A small stack of split logs leaned against the wall—probably the last thing he touched before he died four years ago. “Thank you, Grandpa,” I whispered to nobody and to him, because both felt true. The match burned my fingertips as I coaxed flame into paper, paper into kindling, and finally heat into a room more accustomed to cold. The warmth spread slowly, thin but real. I sat beside it cross-legged, arms wrapped around my knees, and waited for the numbness to take me. It didn’t. The tears came like a storm I hadn’t predicted, racking sobs that made my lungs ache. I didn’t cry quietly. I cried like someone who had been ripped in half and expected to keep walking.

Hours later, with the light gone and the stove ticking, I lit a candle, ate half of a stale sandwich bought with my last ten dollars, and pretended it was a feast. The lights didn’t work. The breaker didn’t either. The house was a museum to a life paused mid-sentence—my grandfather’s mug still in the sink, a pair of boots by the door, a calendar forever stuck on April. I slept fully clothed on top of a dust-choked mattress in my childhood room, my coat for a blanket, my duffel for a pillow, and tried not to think about the woman I’d been just days before: engaged, employed, maybe even happy.

My name is Olivia Reed, and this is how everything fell apart—and then, somehow, how it didn’t.

I met Victor Langston on a Tuesday that smelled like burnt coffee and new beginnings. The high-rise downtown towered all glass and angles, a monument to people whose calendars could crush you. I’d answered a listing for an executive assistant. I had no experience, no connections, just an art history degree, a student loan statement the size of Kansas, and a hunger that outshouted my doubts. The other candidates were older, better dressed, fluent in acronyms I’d never heard. I stayed anyway.

When he walked in, the room recalibrated. It wasn’t just that Victor was handsome; it was the way he wore certainty like a second skin. He stopped in front of me as if we’d already been introduced. “You must be Olivia,” he said, like an invitation.

The interview was short. I stumbled through my answers, apologetic and earnest, but he didn’t seem to mind. He offered me the job the next morning—no trial, no second round. “You start tomorrow,” he said, and the world I thought I might deserve some day arrived in a suit and signed my name on a line I hadn’t dared to picture.

At first, he noticed small things: my clean lines, my tidy handwriting, my ability to anticipate what he wanted before he asked for it. Then came coffees I didn’t pay for, rides home in a car that smelled like leather and power, those casual, precise compliments that shrink an entire universe of insecurity down to one radiant point. “You have an old soul,” he said. “Refreshing.” Somewhere between late-night emails and early-morning meetings, a line blurred. After the company holiday party, with the city glowing under strings of lights, he kissed me in his kitchen and made me feel like a sunrise had picked me, specifically, to wake up for.

He moved me into an apartment I could never have afforded, bought me clothes I’d never have chosen, replaced my purse with one that cost more than my first car. “My girl should turn heads,” he’d whisper as he zipped up a dress I hadn’t known to dream about. I laughed then, flattered. I didn’t see the control dressed as care.

When I told him I was pregnant, I expected anger. Instead, I saw something like relief. “My parents keep asking about grandchildren,” he said with a grin. “Guess that’s off my list.” Then: “We’ll visit them next weekend. Don’t talk too much about your past. Keep it classy.” It sounded like protection. Later, I would learn it was polishing.

He proposed in a tableau he curated for maximum effect, a diamond sliding onto my finger under a ceiling of twinkle lights and applause. He said family, and I believed him. That was before he decided I didn’t belong in the picture he wanted to hang.

It happened a week before our wedding. I was barefoot in the kitchen, toasting a bagel, humming along with Norah Jones and planning a hundred small details, when the front door slammed against the wall like an accusation. Victor didn’t say hello. He didn’t say anything. He marched into the apartment—a storm in a suit—and dropped everything he was carrying like it had offended him.

“Don’t,” he said when I asked what was wrong. “Don’t pretend.”

“Pretend what?” I asked, too calm, as if my tone was a shield that could actually stop what was coming. He tossed down a folder, pages skidding across the countertop.

“You’re carrying someone else’s child,” he said, each word crisp and cold. “Did you really think I wouldn’t find out?”

The world tilted. “No,” I said. “No. That’s not true. This baby is yours.”

He laughed without humor. “You think playing the shy-girl act means I won’t notice you sneaking around?”

“I wasn’t—” I started, and stopped when the truth crashed into the futility of explaining anything to a man who’d already written his version. He stormed into the bedroom, yanked a suitcase onto the bed, started ripping clothes off hangers. I reached for my laptop like a drowning person reaching for a board. “That’s mine,” I said.

“It’s company property,” he said.

“It’s not. I bought—”

“You want to argue over a laptop?” he snapped. “You can keep it. The rest stays.” He gestured at the jewelry, the handbags, the dresses—all of it currency he’d used to purchase my silence and shape my silhouette.

When I tried to slow him down, to make him look me in the eyes and hear the heartbeat that had become the metronome of my days, he moved closer and hissed, “I don’t care who the father is. It’s not my problem anymore. Go trap someone else.” He called two men. They arrived hooded and expressionless, the kind of people paid to shrink rooms around women like me. He had them drive me anywhere I wanted as long as anywhere was away.

“Ring,” he said at the door, palm extended. It caught on my knuckle for a second, as if reluctant to leave. He didn’t look at it when it fell into his hand.

I didn’t cry in the car. I didn’t cry when the men deposited me onto a sidewalk two blocks from the only person I could think to ask for help. Katie, my riotously funny and chronically late friend, opened her door in flannel pajamas and a mug of wine. She took one look, and something in her face broke. “Oh God,” she whispered, and stepped aside.

She made a nest for me on the couch and a pot of pasta that tasted like survival. When she saw my prenatal vitamins on the counter the next morning, she cursed Victor with a creative flair that almost made me laugh. But compassion, like money, is finite when you don’t have much to begin with. She was moving in with her parents to stop the slow leak of rent. She had her own worries. After a week, her apartment got smaller around me. After two, her jokes had grit in them. After three, she asked me to leave, softly, like a request you make to a wounded animal you can’t keep.

I slept in a 24-hour diner, then a bus station, then on the edge of a plan that changed everything. When the forecast promised snow heavy enough to bury even the questions, I remembered the only place I had left: a one-story farmhouse in the Flint Hills, a sagging roof against a bigger sky, a mailbox that hadn’t been opened since my grandfather died. It wasn’t close. It wasn’t warm. It was mine.

The bus left me at a gas station where the cashier didn’t look up. I walked the last two miles with a duffel digging into my shoulder and trash bags cutting my palms, the wind mapping the bones of my face. The key was still in the flower pot on the porch. The smell inside was abandonment: mouse droppings, mold, and a trace of something good that made my throat close—linoleum after rain, a boiled potato, a particular brand of dish soap.

I cleaned until my lungs hurt. I lit candles and watched them gutter. I found a camping stove in a closet and an old kettle. I stacked logs by the stove the way my grandfather always had—crosshatch, not tepee—and coaxed another small warmth into a room that didn’t think I deserved it.

On the third day, I found a letter wedged in the rusted mailbox. The postmark had faded from yellow to memory, but the handwriting was unmistakable. Livy, it read, if you’re reading this, you came back. This house isn’t much, but it’s yours. Tear it down. Rebuild it. Live in it. Just know you’re never as alone as you think you are. Love you forever, Grandpa. I pressed paper to my chest and cried a cry that cleans instead of floods.

The snow arrived like a blank page. I was taping plastic over the worst of the window frames when I heard footsteps on the gravel, that crisp measured sound you can hear invitations in if you’re not careful. A man in a heavy jacket and scarf stopped at the edge of the porch, a grocery bag in one hand and a shovel in the other.

“You must be Olivia,” he said, voice steady, respectful. “I’m Daniel Walker. My dad used to look in on this place. I saw smoke from the chimney and thought—well. Thought someone might need this. The storm’s going to throw a tantrum.” He set the bag down, stepped back like he knew something about skittish creatures. “No pressure. Just welcome back.”

He didn’t linger. He didn’t ask questions. In the bag: bread, soup, bottled water, instant coffee, batteries, and a bottle of prenatal vitamins that made my knees hit the floor. I hadn’t told anyone out here about the life I was carrying. He’d noticed. He’d chosen kindness. I didn’t know what to do with that kind of grace except hold it with both hands.

He came back three days later with a toolbox and a bucket of nails. “Roof needs patching,” he said. It did. We worked mostly in silence—me holding boards while he hammered, both of us listening to the wind negotiate with the eaves. He was a careful man. He didn’t pry. He didn’t assume. He didn’t make me small to make himself useful. Our rhythm settled: every few days a knock, a short conversation, a small mercy—firewood, a coat, a piece of advice about a pipe that wheezed like it was complaining.

Kindness has a way of loosening bolts you didn’t know were rusted. Something in me thawed. Not trust, not yet. Something adjacent: the idea that not everything has to stay broken.

Part Two

The envelope from my attorney arrived with a court date printed on it like a dare. I stared at my name as if it might belong to someone equipped for what it asked of me. It didn’t matter. There was no one else coming. I told Daniel I’d go alone. I needed to weigh and feel and carry this myself. If I fell, I wanted to know which part of me was strong enough to get back up.

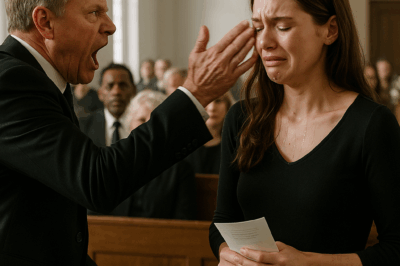

The courtroom smelled like old paper and winter coats. Victor’s lawyer had the practiced nonchalance of a man who uses other people’s money like it’s a licorice whip. Victor was immaculate, of course, annoyance skimming his face like a perfect tie bar. He didn’t look at me. He had never really looked at me.

I looked like resilience in thrift-store boots. For months, between firewood and fixing leaks, I had become my own private investigator. I traced account numbers and dates on legal pads, circled transfers and initials that didn’t belong, compared a prenup we’d signed with the one they produced—and noticed the signature on page five had a loop Victor always formed counterclockwise when he was drunk and clockwise when he was sober. I lined up numbers like soldiers until they told a story that wasn’t the one he’d paid to have written.

When I slid those documents across the table to my attorney, I watched Victor flinch the way a man flinches when he steps inside a trap he built for someone else. Tasha asked the judge to freeze his accounts pending investigation. The judge looked down, looked back up, and said, “Granted.” It didn’t sparkle. It didn’t sing. It was a clean click as a lock turned in a door that had been open too long.

Victor didn’t speak to me in the hall after. He spit instructions into his phone and moved through the building like gravity should have moved for him. I didn’t move either. I let the cold marble press through my shoes into the bones of my feet and thought about how much lighter you are when you’re not carrying a man’s permission to exist.

Back in Flint Hills, winter had softened. The first time I opened a window without losing all my heat, I cried. Daniel stood at the bottom of the steps with a shovel across his shoulder and grinned. “You look like you won the lottery,” he said.

“I figured out how to stop the draft in the bedroom with bubble wrap and duct tape,” I told him.

“That is better than the lottery,” he said seriously, and I laughed in a way that didn’t hurt.

The day I went into labor, the sky was so clear the stars looked arrogant. The hospital in town was small and kind. Dr. Hayes had hands that knew what to do and a voice that never hurried me. My daughter arrived fierce and perfect, red-faced and indignant. She grabbed my finger like we had an agreement she planned to hold me to. I named her Hope. Not because I needed poetry, but because that’s what she was before she had a face.

Daniel brought cinnamon rolls and pretended not to notice when I cried because crying gave the joy somewhere to go. He didn’t ask if I’d picked a middle name because he learned me without a study guide, but when I said “Eleanor,” he nodded like somebody had made a good edit. He didn’t press when I added, “Not for anyone you know. For the woman who taught me who not to become.”

I didn’t go back to Topeka after the accounts were audited and the numbers did their careful work. I didn’t need to say one last thing or gather any more apology that would have turned into quicksand in my mouth. The settlement returned what was mine, not everything Victor had tried to take, but enough to say I hadn’t been written out of my own story. I didn’t want his money. I wanted the math to line up in a way that let me sleep. It did.

Spring arrived like a reinvention. I planted tomatoes in ridiculous optimism. I sanded the porch swing until it no longer snagged sweaters. I painted the nursery a color called Something Seed (which is to say: green), and strung a strand of little paper stars across the ceiling. When I found an old rocking chair at a yard sale and carried it to the car by myself, I felt something click back into place that had been loose too long.

Sometimes, at night, when the baby finally slept and the house sighed as old houses do, I’d sit on the porch and listen to coyotes propose to the moon. The frost left messages on the railing one morning—her name in delicate crystal script. I hadn’t written it. Neither had Daniel. I don’t pretend to believe in signs anymore, but I stood there until my feet went numb and said, “I see it. I see her.”

On a grocery run in town, my cousin Natalie hugged me in the cereal aisle and told me Vanessa’s wedding had landed on the front page of common sense. My parents had mortgaged their house to pay for champagne fountains. The house was now a story in past tense. “They’re living with her for now,” Natalie said. “It’s… tense.”

When my father knocked on my door months later, he looked like a truth-teller. He said, “I’m sorry,” and it wasn’t press release sorrow. It was the kind you say bent over because the thing you did weighs more when you finally stop shifting your weight away from it. “I was a coward,” he said. “I saw it and I didn’t stop it. I feared conflict more than I loved you well.”

“I appreciate it,” I said. “It doesn’t fix it.”

“I know,” he said. “I want to be the kind of man who shows up for his granddaughter. I don’t expect to be in the front row. I’d like to be in the building.”

He earned the building, then a row near the middle. He did small things without announcing them. He took the trash out without commentary on the strength of my bags. He brought a quart of paint and a roller and asked where to start. He didn’t speak ill of my mother in my living room, even when the silence hurt. That’s how you repair a thing you broke: you do ordinary service without asking for applause.

At Aunt Darlene’s sixtieth, I saw my mother across a room that suddenly seemed very small. She walked up to me, pride and grief in a tense truce in her face. “You look well,” she said.

“I am well,” I said. She said she was sorry things had happened as they did. I told her mistakes are forgivable; deliberate harm is something else. She said she did what was best for Vanessa. I said, “Always Vanessa,” and the conversation ended like a door gently swinging closed. Some endings don’t slam. Some endings take your hand off a hot stove and put it under cool water.

Daniel asked me on a mild spring night if we could talk about making our own family bigger on purpose. “Not to fix anything,” he said. “Just because you would be so good at it.” We were already good at it. We practiced every day in the way we spoke, in the way we didn’t, in the way we held each other to the best version we believed in.

Grace arrived nine months later with a laugh like a small bell. She calmed in Daniel’s arms the way people calm in rooms with open windows. She calmed in mine because I sang while I was terrified, and children understand bravery isn’t the absence of fear; it’s staying anyway.

Sometimes the past still knocks. Sometimes it sends a text from an unfamiliar number that turns out to be your sister’s voice saying, “I’m sorry,” small and human and not a script. “I don’t expect forgiveness,” she says. “I’m trying to change.” I say, “Thank you. Keep doing the work,” because forgiveness is a bridge you build from both sides, and I have a baby on my hip and a paintbrush in my hand and I cannot carry other people across gaps they refuse to see.

Our life is not cinematic. It’s better. It’s grocery lists and the soft click of a door Daniel fixed so it doesn’t bang. It’s Grace’s fingers in the dirt, discovering worms with a delight so pure it makes me trust the world again. It’s the neighbor who taught me that good men don’t ask for your story before they decide to be kind. It’s the message written in frost that nobody saw me write because I didn’t. It’s the court where numbers mattered more than charm. It’s the farmhouse where I learned to breathe again.

Sometimes, when Grace is asleep and the house is loud with quiet, I think about the woman who sat on a dirty floor and decided to live anyway. The one who carried a letter in her pocket because it was the only thing that told her she was somebody’s. I know her better now. She didn’t need a storm or a siren. She needed a match and a stove and a reason. She needed to lose what wasn’t love to make room for what was.

I used to think the worst thing was being broken. The worst thing is believing you can’t be put back together. You can. Not the way you were. The way you’re meant to be now. With scars that teach you where the soft spots are, with hands that know how to hold a nail steady while you swing the hammer, with a daughter who says “Mama” like a prayer that worked.

Some stories don’t end with revenge. They begin with it, then soften into something braver. Mine started with a door slammed in my face and ends, for now, with a baby reaching for a butterfly on a porch I rebuilt. My life is not what I was promised. It is better than what I was told to settle for. And if you are standing in a room drafting a survival plan by candlelight, hear me: there is a morning coming where you will not recognize the sound of your own laughter and you will be grateful anyway.

You are never as alone as you think you are.

END!

News

Airport Security Dog Wouldn’t Stop Barking at a Pregnant Woman — Then Everyone Learned the Heartwarming Truth. ch2

The winter morning at Brighton International Airport had been humming along in its usual way — rolling suitcases clicking over the tile,…

“My Mommy Won’t Wake Up…” — The Cry at the Airport That Sent a K9 Officer Racing Against Time. CH2

The airport was unusually quiet that Sunday morning. Officer Janet Miller adjusted her duty belt as she and her K9…

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”— So I Chose Revenge. CH2

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me and Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”—So I Chose Revenge Part…

My Brother Kicked Me Out After My Divorce, So I Prepared an Unexpected Surprise. ch2

Part 1: An Unexpected Betrayal I stood in my brother’s marble-floored foyer surrounded by moving boxes and the remnants of…

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global. CH2

My Brother Called My Career “A Joke” At Family Dinner, But They Regretted It When I Went Global Part One…

Jeanine Pirro and Tyrus Declare War on CBS, NBC, and ABC—With $2 Billion Backing, Fox News Makes Its Move. ch2

In a shocking move, Jeanine Pirro has declared war on CBS, NBC, and ABC, and she’s not doing it alone….

End of content

No more pages to load