“Parents Called My Research ‘Worthless’—Until Big Pharma Called”

Part One

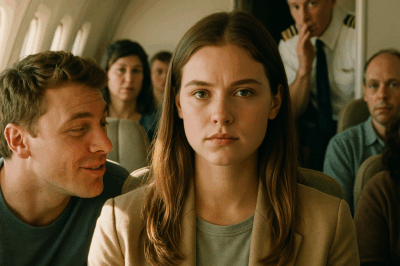

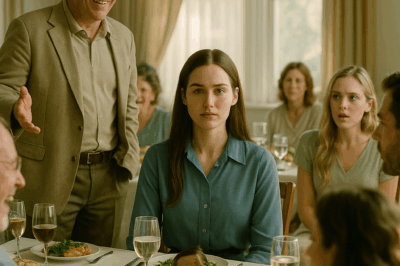

The family dining room felt smaller than it had any right to be. It was never a small room—mahogany table, upholstered chairs, a chandelier Dad bought after he made chief of surgery and Mom pretended to dislike until the society pages called it “tastefully restrained.” But that night, the air was crowded with disapproval so thick it felt upholstered too. Mom’s designer blouse and Dad’s hospital badge seemed to expand and push outward, framing the conversation the way crown molding frames a ceiling. My sister Diana slung her white coat over the back of a chair like a trophy, the logo from her prestigious cardiology practice positioned so the monogram stared at me across the table.

I sat in my lab coat. Not the crisp, photo-op kind, but the one with coffee stains at the cuffs and a rip at the hem I’d mended badly with blue thread from a sewing kit the lab manager kept behind the autoclave. They’d mocked that coat more than once. Tonight, it warmed my forearms like a secret. In the left pocket—under a wadded sticky note with a chemical shorthand only three people on earth would recognize—were over a dozen hand-scribbled annotations to a protocol worth more than this house. Worth, though I did not yet allow the thought to fully form, more than the combined salaries in this room would ever be.

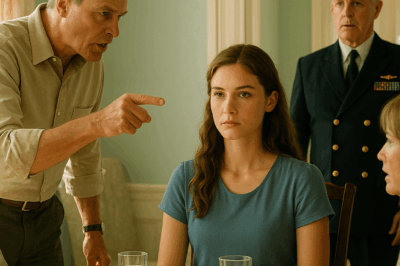

“Catherine.” Dad used the voice that made residents stop breathing. He didn’t need the operating theater tonight—the din of cutlery against porcelain, the white glow of candles reflected in every polished surface, the faint clink of ice in Mom’s water glass were accessory enough. “This has gone on long enough. Your mother and I are concerned about your career choices.”

I glanced down at the phone on my lap and saw the push notification I’d been silently tracking all day: Clinical Trial, Phase III: Interim analysis uploaded. The screen lit my coat like a supernova in miniature. I angled it so the light didn’t show. The app that mirrored our trial database gave me a preview: promising. More than promising. I pressed my knuckles against the table’s underside to keep my face still.

“The lab work is progressing,” I said. I kept my voice steady, the way I’d practiced in after-hours runs on the flow cytometer: slow, precise, no wasted energy.

“Progressing,” Diana repeated, with the little snort she used on interns who spelled pericarditis wrong. She adjusted her watch—the one a grateful patient had gifted her, diamonds that caught the chandelier and threw little judgments across the tablecloth. “You’ve been stuck in that university basement for five years. I’ve built an entire practice in that time. We just opened a second location.”

Mom sipped her wine. The ring Dad bought for their twentieth caught the light and performed. “Darling, your sister’s practice is thriving.”

“So is my lab,” I said.

“Your trust fund isn’t infinite,” Dad said. “And your portion is nearly depleted.”

“I haven’t touched the trust fund.” My fork scraped my plate louder than I meant it to. “Not in three years.”

Mom choked delicately into her glass. “Then how are you… I mean, the university—surely they can’t be paying you enough for—”

My phone vibrated again. Then again. The vibration skittered against the wood like a trapped fly. I slid the device out and thumbed the screen under the table. Embargo lifts at 7:00 p.m. Patent status: GRANTED. Licensing inquiries: 43 and counting. A banner across the top from a news app I never turned on for anything but hurricanes: BREAKING: Revolutionary cancer treatment announced; Phase III remission rates shock oncology community. Big Pharma in bidding war.

The TV over the sideboard, tuned as always to financial news on mute, suddenly switched to a breaking banner with a red strip so urgent it seemed to pull color from the room. The anchor’s mouth moved rapidly as a lower-third scrolled: UNIVERSITY RESEARCH TEAM UNVEILS GROUNDBREAKING ONCOLOGY PROTOCOL. Then—my photo. Not the headshot I would have chosen (I looked sleep-deprived and victorious), but unmistakably me. Clips of our lab. Clips of our early-stage trials I’d never seen edited into anything but spreadsheets. Clips of a whiteboard with my handwriting on it, my crooked arrows, my molecules.

Dad’s reading glasses cracked in his grip. A hairline fracture shot across one lens, then another, and for a moment I thought we would finally match in how we were seeing the world.

“That’s…” Diana’s composure slipped. “That can’t be—”

“Actually,” I said. I put my phone on the table and let it glow. “It is.”

The room rearranged itself around those two words. It didn’t get bigger, exactly, but the walls stopped pressing so hard. I watched Mom’s face go through stages as if she were inventing them as she went: denial, confusion, calculation, hope.

“But y-you’re always working such long hours,” she said, stammering the way she never stammered in front of other women at charity events. “Those weren’t… you never published anything significant.”

“The embargo lifts at seven,” I said. “Thirty-seven papers. We held everything to protect the patent. Couldn’t risk a leak.”

The house phone rang. No one moved. My cell lit: NEJM editorial desk. I declined, then pulled up the list of journals with scheduled releases: Nature Medicine, Lancet Oncology, Cell, Science Translational Medicine. Slide decks loaded beneath each title like planes on a runway, ready for takeoff. A separate window showed our patent grant, the seal bright and ridiculous and very, very official.

“Those cell cultures you mocked?” I said gently. “Those ‘endless experiments’ that ‘never go anywhere’? They’re the core of a protocol that just changed first-line therapy for three of the most lethal cancers we treat. And if our biomarkers keep behaving, we’re talking about more.”

Onscreen, the news cut to a patient video from one of our trial sites: a woman in her fifties standing in a hospital room, her hair already starting to grow back, laughing through tears as a nurse pulled the IV from her port for the last time. In front of her was the bell.

Diana’s phone quivered across her plate with messages from doctors who used phrases like holy hell and Catherine Hamilton and is this your sister. Her thumb flew. Her mouth opened twice and managed no sound.

Dad cleared his throat, his voice smaller. “Your… lab equipment. All those funding requests. Did they—”

“Pay for themselves a few thousand times over,” I said. “And a bit beyond.”

The lower-third updated: Merck, Pfizer approach university for exclusive rights; preliminary bids rumored to exceed $8B. I watched a grainy clip of our campus gates choked with satellite vans. The news channel switched to footage from our Phase III: survival curves curving in ways my discipline had not historically allowed itself to dream. A bar chart floated up with numbers that would have made my doctoral self faint.

“Our remission rates are not an accident,” I said. “They’re the outcome of five years of basic science, two of translational work, and the last eighteen months of clinical trial design executed by a team that slept less than any of you and believed more than all of you.”

Mom’s mouth had softened into something almost beautiful—unadorned, without social calculus. But then I saw the old reflex try to reclaim ground. “This is wonderful,” she said, slipping on pride like a borrowed shawl, “and of course we always knew you were brilliant, no matter what some people might have—”

“Don’t,” I said. I kept my voice even. “Let the university PR team handle family statements. There’s proprietary data in the press packet, and I can’t risk a stray quote. They’ll send you talking points.”

“Talking… points,” she echoed, faint.

The university president’s name lit up on my screen with the preview bubble: Pharma reps overwhelming licensing. I texted him: I’ll be there in twenty. No exclusives. Then, to my team thread, I sent one word: Now.

At the edge of vision I could see Dad trying to reassemble the version of the world where he had been right. Easy to do on a cutting board with severed vessels that can be tied; less easy, I suspected, with a daughter whose career he’d called juvenile now occupying every screen he owned. Diana was rapidly reading the abstract of one of our papers, tapping through to the methods and then to the supplementary figures, her surgeon’s confidence collapsing a little with each line of molecular biology not written to flatter a cardiologist’s fluency.

“Those compounds you’re always ordering,” she said finally, as if she had to anchor to something ordinary. “The ones I told the committee were basic research supplies. They were… the breakthrough molecules.”

“Each synthesis worth more than your entire practice,” I said before I could stop myself. I heard how unkind it sounded and added, because truth can be tender even when it is unsparing, “And worth less than the remissions. That’s the valuation that matters.”

The bell on TV rang. In living rooms across the country, people leaned in and cried.

“Come with me,” I said, standing. “You wanted to talk about my career choices. You’ll get all the data you can handle.”

Through the glass wall of the press room, I could see them later—my family clustered under a photo of a past Nobel laureate who’d once visited campus, watching me not as a daughter to be corrected but as a scientist on a stage that held more wires than flowers. My team—Sarah, my lead researcher; Luis, who designed our best assay with a pencil on the back of a pizza box at 1:13 a.m.; Priya, who could coax reluctant cell lines into cooperation with the patience of saints and saboteurs—all filed in behind me like oxygen.

“Phase III interim,” Sarah whispered, not bothering to hide the grin she used only at the bench. “Better than our projection. Eighty-nine percent complete remission. Ninety-five percent progression-free at twelve months.”

A gasp went through the room like a small wind. Behind the press pit, a cluster of suits in lanyards shifted—pharma emissaries from companies that used to take my calls when they wanted to borrow postdocs for focus groups and ignore them when the grant season didn’t require humility. The summary of their offers flashed across a monitor in the back like a scoreboard: $8.2B, $8.5B, a number that made the president’s eyes shine.

“Dr. Hamilton,” he said to me under the murmur, “Merck is prepared to—”

“No,” I said softly. “No exclusives. No monopolies. Controlled, fair licensing across qualified centers, tiered pricing by country, immediate compassionate use where indicated. Our protocol does not belong in a vault.”

Mom, behind the glass, put a hand to her throat as if I had physically stopped a check from clearing. Dad leaned forward, trying to hear.

“We believe,” I said into the microphone when the reporter from Nature Medicine called my name, “that saving lives is not a luxury product. We will license non-exclusively with strict quality controls and a pricing framework negotiated with global health partners.”

“The WHO is on line one,” an assistant whispered, panic and wonder braided into one thin rope.

“Put them on the second screen,” I said.

I wasn’t performing humility when I said it. I was performing the work. The chemistry of our molecules was elegant, sure, but the chemistry of access was more complicated than anything we’d synthesized, and less forgiving. If you get it wrong—if you tune the price a degree too high, if you restrict distribution a fraction too much—people die as surely as they do from a poorly designed drug.

We walked through mechanism of action—our compound’s elegant dance across receptors that chemotherapy had always trampled; our immunomodulator’s way of teaching a body to see what danger looks like without burning the house down to reach the thief. We walked through inclusion criteria and biomarker thresholds. We walked through adverse event profiles, through the rare but serious cytokine storm one of our sites had seen and how we had managed it quickly with a protocol that would be printed on the back of every badge in every trial room in three languages before the week was out.

I will not lie: it was intoxicating to watch the skeptics recalibrate. Dad’s texts pinged my screen as if he could text the tide back: Proud of you—a phrase I’d wanted for twenty years and finally understood I had not needed. Diana’s partners buzzed her phone with We need to get on this and Bridge our oncology service to the protocol ASAP. Mom was, as ever, calculating the optics, sending messages to her charity board about how “our family” had always “prioritized” research, even as I projected onto the wall the screenshots of her texts six months earlier calling me impossible and ungrateful for missing a gala to run a 48-hour assay that ended up saving three trial patients’ lives.

Reporters asked about money. I told them about metrics: survival curves, QALYs, the maps of deserts on the globe where our default infrastructure had marooned the sick and how we intended to build roads out of policy and steel. I told them about an advance purchase agreement with an African consortium that would ensure first-year access in countries that had historically been asked to wait a decade for the therapies their patients died without. I told them my trust fund—Dad’s favorite cudgel—had been emptied three years earlier to fund our earliest assays and, today, would be replaced by a philanthropic arm endowing fellowships for researchers who dared to do something impolite with their lives.

You can tell when a room shifts from curiosity to belief. It’s almost audible, like a lock turning. When the questions changed from why should we to how fast can we, I knew.

By the time the press conference ended, my phone’s battery had a sliver of red left and the corridor outside was constellated with lanyards bearing names that would have made the version of me who once went into debt for a conference registration weep. We broke into work teams: legal here, global implementation there, manufacturing in an overflow room with engineers sketching the inside of their heads onto whiteboards while someone ordered food that would mostly go cold.

I stepped out of the conference room into the glass-walled corridor, where my family waited like a painting of itself. The hospital board had called Dad three times while we were on the dais. Diana’s practice partners had texted six times, then stopped, then texted again—panic disguised as strategy. Mom’s charity board had asked whether we could arrange a lab tour for a fund-raising “experience.”

Security had already told her no. Biosecurity protocols, the guard had said with the exact tone you use when a person tries to walk into an operating room with a handbag.

“Catherine.” Dad stood. He looked… small, and then, in a different way, human. “We didn’t know.”

“No,” I said. I did not make my voice unkind. “You chose not to.”

Mom flinched as if I’d pushed her. “We were only worried.”

“You were only proud of the thing in the white coat you could understand.”

Diana opened her mouth, closed it. “It’s… brilliant,” she said finally, the word dredged up like a confession. “Your mechanism. The kinase cascade—how it—” She broke off, and when she looked up she wore something like humility. “I’d like to understand it.”

“Read the methods,” I said. “Then shadow the tumor board next week. If you can sit for three sessions without posting on social, we’ll talk about your clinic becoming a secondary site.”

Her eyes filled. She nodded. For the first time in years, I believed she was looking at the same room I was.

Mom’s voice was thin. “Your father’s hospital wants… a partnership. Perhaps they could be an anchor site. I could—”

I cut her off because time could not be spent in lessons already taught. “The protocol speaks for itself,” I said. “It doesn’t need what you call ‘introductions.’”

“What about family,” she said. “We are… your family.”

“I will always respond to mom, not to brand,” I said. “If you want to come to the house for dinner and hold in your hands the proof that I exist beyond board positions and donor lists, you can. If you want me to walk you through the step where you see me as I am, I will try. But you don’t get to bring a camera crew.”

Dad swallowed. “The hospital board is… reviewing my position.”

“They will,” I said. “You may yet serve. But if you do, it will be because you adjust. Not because you insist.”

In a room behind me, the WHO was waiting. In a hospice three states away, a woman was watching a segment about our trial and allowing herself, for the first time in months, to imagine that the cake she had promised her granddaughter might actually be baked. I excused myself and walked toward the job I’d always had. As the door closed, I heard Mom whisper to no one in particular, “We didn’t know she was… this.”

I smiled in spite of myself. Neither had I. Not like this. Not with cameras and heads of state and a calendar portioned into slices too thin to taste. But I had known something they hadn’t: that worth is not the sound a family makes when it finds itself on the right side of a headline.

I put the lab coat back on and went to work.

Part Two

Three months after the press conference, the research center thrummed like a heart that had found its rhythm. On the wall-size displays in our command room, real-time data flowed from hospitals on five continents. Recovery rates bloomed like orchards in regions where numbers had once been wastelands. Survival curves flattened death’s easy arc and lifted it away. A dashboard tracked manufacturing yields against uptake, shipping routes against heat maps of demand, adverse event reports against the standard we now insisted upon.

If the first part of my life had been about knowing how to generate a signal from noise, this part was about knowing how to keep the signal clean when a world newly devoted to believing is also newly talented at lying.

Every morning began with triage: open licensing queries, center audits, Q&A with a rural oncology team in Peru whose success rate was already outpacing urban neighbors because they’d chosen a nurse with hands like patience to run their program; a late-night call from a pediatric unit in Johannesburg adjusting biomarker thresholds to capture a subset of children our adult trials hadn’t seen.

Between those calls and the meetings with manufacturing partners, I taught. Not in a classroom—no time, not yet—but in the rooms where decisions took breath and shape. I drew the kinase cascade at least forty times that month, on glass, on whiteboards, on a napkin once for a minister of health who kept that napkin as if it were a saint’s bone.

Sometime around the point the data made skepticism look outdated instead of rigorous, the family machine—my family machine—cranked back to life. Their text bubbles offered everything they’d once withheld: connections, resources, respect. The hospital that used to use my name in a tone reserved for unsanctioned experiments asked to become a primary site; the private practice with my sister’s initials in the logo asked to be a secondary; Mom’s charity asked to “host” a patient story evening in our lab, as if the lab were a ballroom and hope a centerpiece.

I held my line with a steadiness that surprised me. The university’s security team had made it easier; biosecurity was a word with teeth, and I leaned into it. When Mom arrived at the lobby with a board of donors and a photographer she promised was “discreet,” security turned them away. She called me, crying the kind of tears that used to make me go limp with guilt. “We didn’t know,” she said again.

“No,” I said. “You did. You knew I asked for privacy. You decided your story mattered more.”

On the command room’s back wall, a small blue dot pulsed—Mayo Clinic’s pediatric oncology department, requesting expanded access for the protocol in a trial we hadn’t expected to be ready for another quarter. I forwarded the request to Sarah and felt that bubble of fear that I now recognized as awe. If we were careful, if we were humble and lucky and thorough, children would grow up with the memories their parents had asked picturing.

Our in-house AI assistant—nicknamed Medica by a postdoc with a sense of humor and the power to create acronyms on the fly—glowed up on a screen. “Dr. Hamilton,” it said in the voice I’d insisted we keep unanthropomorphized, “the World Health Organization is ready to finalize the tiered pricing framework. Also, the University Board would like to discuss naming the new wing.”

“Not after a donor,” I said, at the same time. “After the first patient who rang the bell in our trial. Find her name.”

“Found,” Medica said a breath later. “Ava. Eighty-one days from first dose to complete response. She’s knitting now. It’s on Instagram.”

“Ava it is,” I said, and felt my throat go hot.

When Medica paused, I knew there was something it was trying to deliver gently. “Additional updates,” it said. “Your father’s hospital board has tabled his bid to lead the new oncology initiative; archives show his public comments on research. Your sister’s clinic has lost three oncologists to our partner centers; they’ve submitted an application to join as a tertiary site.”

“Evaluate the clinic,” I said. “On merit. Not on blood.”

“Yes,” Medica said. “Preliminary review suggests they need to partner with an academic center to meet our audit standard.”

“They can partner with Dad’s hospital,” I said. “If Dad shows up to the research meeting with a notebook and not a speech.”

That night, Dad texted: Can we talk? Alone. I met him on the bench outside the campus café where he used to sit on Sundays critiquing my essays under the guise of “help.” He did not bring a lecture. He brought a paper cup and two hands that shook slightly.

“I took the board seat,” he said without preamble, “because I wanted to feel useful when I stopped cutting. I kept it because it felt like affirmation. I’m not here to defend what I said about you. I’m here to say I was wrong to say it, and wronger not to know why I was saying it.”

I watched him watch a student bike past balancing a takeout container in one hand and a future in the other. “I slept through the part of medicine where curiosity replaced certainty,” he said softly. “I want to wake up.”

“Then read,” I said. “And listen. We hold tumor board on Wednesdays at 6:00 a.m. There’s coffee in the back. No speeches.”

He laughed and cried at the same time, one of those endearing, embarrassing human noises I realized I’d missed.

Diana came by the lab the next week. She wore her white coat without the logo. She kept her phone in her pocket and took notes. She watched the team discuss an adverse reaction that had frightened us the night before and watched how fear and thoroughness braided together in the hands of people who refused to choose between zeal and caution. Afterward, in the hallway, she said, “I told myself I hated basic science because it was slow. I think I hated it because I was afraid of what it reveals about my pace.”

“You can learn a different one,” I said.

She nodded. She asked if she could sit in on patient education sessions once our center opened to referrals outside the trial. “If you can keep your hands still,” I said, and when she looked at me in confusion, I took her to the observation window where a nurse, Anjali, was demonstrating the injection device to a patient’s husband, and pointed to how Anjali kept her hands flat and visible at chest level so the husband would not feel directed but invited.

Mom took longer. Our worst fights were not about the science; they were about the story. She still wanted to write one where the parts she had played mattered more than the part where I stayed in a lab for weekends that had names and Sundays that had sunrise. When the Nobel Committee called the university to “preliminarily” inquire about my availability “for a potential” something, she forwarded the press release before it existed to three women who had never learned to clap without also calculating the decibel level.

In the end, I handled Mom the way I handled a recalcitrant cell line: with boundaries and patience, in that order. I sent her the public sign-up link for our patient story evenings—the ones held in the auditorium, not the lab, the ones with scripts and consent forms and photographers hired by us. She came. She sat in the third row next to a woman whose hair had only just begun to sprout and whose son clapped off-beat and joyfully when the bell video played. Mom brought tissues and used them on herself and on the stranger who leaned against her shoulder without asking permission. Afterward, in the hallway, Mom said, “I forgot that success could look like this.”

“Success looks like a hundred different things,” I said. “Most of them not on television.”

When the first full year closed, we threw a party that looked nothing like the ones Mom had planned and exactly like what I had wanted: a potluck. Nurses brought rice dishes that smelled like home. A data scientist baked a cake shaped like a Kaplan–Meier curve and the interns laughed so hard several almost hyperventilated. In the corner, a group of patients and parents—some from our trial cohort, some from early implementation sites—stood together, eyes on nothing but each other, the way you look when you’ve traversed something unspeakable and want to speak anyway.

Dad came late. He had a notebook in his hand. He wore an expression I recognized from when I was little and he fixed a bird’s wing with a string and a Popsicle stick while telling me it would live, and then it did. He hugged me, brief and sturdy. “I’m learning,” he said. “Your tumor board is brutal.”

“It’s kind,” I said. “We confuse the two because we grew up in rooms that called performance kindness and silence care.”

He nodded. “You were never worthless.”

“No,” I said. “I was not.”

We built the Ava Wing with glass and grace notes. The entry plaque carried her name and the names of the first five patients who had taught us where the protocol bent and where it must not. We funded ten fellowships by selling nothing to no one and by reinventing what we meant when we said “profit.” We kept our licensing fair and were called naïve; we kept our audits strict and were called cruel. The truth, as ever, sat between.

One night, months later, as I was leaving the lab, the security guard—Marcus, who had started saying “evening, Doc” with a glow I never got used to—said, “There’s someone waiting in the lobby for you.”

A woman stood when I approached. She was in her forties; she wore a blouse that had seen careful ironing and an expression that had seen something you don’t prepare for. Her child—teenage, wiry—sat beside her, flipping a coin in a palm with the aimless grace of adolescence.

“I’m Rosa,” she said. “You don’t know me. My hospital used your protocol.”

I gestured toward the seating area. No cameras. No podium. Just a bench and a machine with bad coffee.

“It worked,” she said. She said it with the simplicity you use when you have no energy left for adverbs. “I rang the bell.” Her son looked up and smiled the smile of someone who knew he would get to be a man. “They told us to thank the team,” she added quickly, the way good patients try to distribute their gratitude equitably. “And we do. I just… wanted to tell you I know you missed your sister’s ribbon cutting you never heard the end of.” She laughed. “The nurse told me. The one with bracelets up her arm, she talks too much.”

“Anjali,” I said, and felt my eyes water.

Rosa leaned forward and put both her hands over mine with an intimacy that would have startled me in any other context and felt inevitable here. “It wasn’t worthless,” she said. “Whatever they said. It wasn’t.”

“I know,” I said softly. “I know now.”

The Nobel Committee called again. I didn’t change my ringtone. Awards came. I wore the good dress, I thanked the right names, I went home and changed into jeans and went back to the lab because the lab did not care what Stockholm thought. We found a biomarker that made our pediatric cohort safer; we discovered one that excluded a subgroup we’d hoped to help and learned to say not now without making not ever a sentence. We made mistakes; we told the truth about them and were accused of being either too proud or not proud enough. Humans wrote the commentary; humans benefited from the care.

On a holiday that had once been a minefield, I invited my family over. Not to celebrate my prize or my protocol or my photo in a magazine I kept forgetting to recycle, but to eat. I cooked a stew that tastes better the second day and set out bowls and did not make a speech. Dad arrived with flowers from a corner store and a foil-wrapped pie he had probably purchased on the way, and I loved him for both. Diana brought a salad that would have made fun of itself if it could—three kinds of microgreens trying to be a forest. Mom brought napkins; she tried to bring a story and left it in the car.

We ate. We cleared. We carried plates into the kitchen and out again. No one asked me to explain my job in a way that would look good on a donor slide. No one weighed my worth against their comfort. The bell video played on my laptop because the twins from Rosa’s city had sent it to me and I wanted to watch again. We watched it together. Dad cried openly. Mom reached for his hand the way she had when they were both twenty-four and poor and believed they were the exception to every rickety rule.

“Do you forgive me?” Mom asked later, when we stood on the porch with mugs cooling in our hands.

“I forgave you the day I chose to stop needing your apology to live,” I said. “But yes. And no. And we will do this slowly.”

She nodded. It was the most adult thing I had ever seen her do.

Weeks turned to quarters. Our protocol met competitors and collaborators. We added a second indication; we failed at a third. We trained nurses in rooms with crayon drawings on corkboards and surgeons in auditoriums with portrait oil paintings. We fought with regulators for speed and with ourselves for caution. We answered calls at 3:00 a.m. from a clinic whose freezer had gone down and stayed on the line while someone they loved cried in the background for reasons that had nothing to do with cancer and everything to do with life.

My trust fund—the one Dad used to dangle like a leash—had been replaced by a fund whose only leverage was wonder. We called it the Worth Fellowship, partly because scientists cannot resist a pun, and partly because in our application we asked one question only: What is the work worth doing that your world keeps calling worthless? We funded twenty-two fellows the first year with money that would have bought my mother three more chandeliers. They built exoskeletons out of cheap parts; they mapped lakes of antibiotic resistance in communities nobody maps; they taught an algorithm not to be a racist by refusing to feed it the data of our laziness.

And Big Pharma? They called again and again. We said yes again and again to manufacturing and distribution and audits and training, and no again and again to exclusives that would turn our patients back into markets and our molecules into a badge. Some called me naïve. It turned out many of the people who used that word had never met a mother in a lobby whose son had almost not become a man.

On the anniversary of the night the TV in my parents’ dining room turned me into a person they would have to learn how to see, we went back there. Not to reenact anything, but because Dad had had the chandelier taken down and replaced with a simpler fixture he claimed was “too dim for the surgeon’s wife” and “just right for me.” The table had new scratches mine among them. We ate, we argued kindly, we watched a child next door ride a bicycle badly and then beautifully. When we left, Mom hugged me with her eyes closed. “I stopped telling the story where I was the hero,” she said into my shoulder. “It’s a better story now. I didn’t know.”

“You do now,” I said.

I got into my car and watched them in the doorway, a composite of their best and worst choices. I turned the key and thought—because it is true and because I earned the right to say it without flinching—I was never worthless. I had been expensive and exhausted and excellent. I had been inconvenient. I had been young and wrong and stubborn and right. I had been a lab coat with stains and a pocket full of molecules and a phone with a battery that held on until it couldn’t and a voice that was quiet until it wasn’t. I had been a daughter. I was a scientist. I would be both.

On the way home, my phone buzzed. Another hospital, another map pin, another life that might soon be a bell. I answered with my hands on the wheel and my heart in the place my mother always told me to keep it: steady, not soft; warm, not stupid. The caller said a name. I said a plan. They said thank you. I said you’re welcome and heard the word finally mean what it always should have meant in our house: I’m glad you’re here.

When Big Pharma had called, I had answered—as a collaborator, not a supplicant. When my parents had called my work worthless, I had answered—as a scientist, not a child. When the world called with the question underneath every question—will it work—I had said let’s find out, and then I had found out.

That is the ending, and the beginning I keep choosing: not applause, but outcomes. Not a fortune, but a fellowship. Not a chandelier, but a bell.

END!

News

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives. CH2

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives …

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load