Parents Banned Me From Thanksgiving After I Paid For It All, But They Faced An Empty Table Instead

Part One

The butcher’s receipt still smelled faintly of smoke and cold air when I slid it into the drawer beside the stove. I’d picked it up that morning on my way to work—the 24-pound heritage turkey my mother insisted made “real” gravy, the kind her grandmother used to make before anyone worried about cholesterol. The invoice listed my name and my card number, a string of digits I could recognize the way some people recognize their children’s school IDs.

“Everything confirmed, Catherine,” the butcher had said, tapping the counter with a pencil. “Pick up Wednesday by noon, oven at 325, breast down for the first hour, you know the drill.”

I knew the drill. I’ve always known the drill.

If you had walked into my childhood home on any Thanksgiving from ages ten through twenty-two, you would have found me at the sink elbow-deep in brine, at the stove swirling gravy until it glossed, at the table measuring distances between plates so the line of flatware looked like a premeditated kindness. The oldest daughter becomes the second parent in houses like ours, but without the credit. The title on my mother’s holiday to-do lists might as well have been Make it look like we’re happy.

I moved out at nineteen but kept coming back on the holidays because that’s what a good daughter does when the family story requires her to. I brought rolls and cheesecake, took coats and compliments meant for the furniture, and bragged about my siblings when no one asked.

This year had felt different in a way I couldn’t name until it named itself.

It started with a chirp. The family group chat—the one with the cartoon turkey icon and the year changed every November—lit up with my aunt’s message: Can’t wait to see everyone! I was at my desk in the office, tray of sticky notes and highlighters arrayed like surgical instruments, when I typed Same. Looking forward to it.

The typing ellipses blinked. Then stopped. Then nothing.

An hour later a private text buzzed from my cousin, Hannah. Are you actually coming? she wrote. Your parents told everyone you weren’t invited this year.

The bottom fell out of something inside me, something I had not realized had a floor until I hit it. My office chair squeaked when I sat back, the sound absurd in the quiet. I called my mother.

“Oh, Catherine,” she said, voice wrapped in a sigh she’d ironed a thousand times. “We decided to keep it small. Just immediate family.”

“I am immediate family,” I said, each word a rung on a ladder I had no choice but to descend.

She mmm’d—one of her non-words she uses to soften blows and sharpen knives. “We just thought it would be easier. Less… tension.”

“Tension?” The only tension I could recall in the last year had been mine, in my neck, from not correcting the stories she told when the edges of facts didn’t suit her decor.

“Your brother and sister will be there,” she went on, dismissing my question the way she always did. “You know how they depend on traditions. And your father invited Eleanor and Jim—oh, they bring such a nice bottle of wine. It’ll be good for Amy to see everyone.”

You can know what a person is doing and still be stunned by it. I hung up. Then—because I was raised to be useful even when unwanted—I placed the orders. I called the butcher. I sent the bakery my mother’s list (two pumpkin, one pecan, one apple with extra crumble). I used my card. The receipts all sat under the weight of a ceramic trivet that said Bless This Mess in a kind of handwriting that makes my teeth itch.

Tuesday morning, I canceled the butcher order with a single phone call and the bakery with two. The butcher grunted, refunded. The bakery owner sighed, mentioned it would be hard for them, relented. I apologized like a person who believes apologies are currency that accrue interest.

Then I waited. Not because I wanted them to suffer. Because I wanted to see what happened when I removed the support beam they had convinced themselves was a decoration.

At 12:17 p.m. on Thursday, my phone lit up: Dad.

I let it ring four times. The fifth buzz buzzed like a heartbeat.

“The food never arrived,” he whispered, stretched thin, like the words had been dried in a hot attic. Voices murmured in the background. The wash of whispers came through the line, smeared into a single syllable: what now?

“Oh?” I said, leaning back on my kitchen counter miles away. “I didn’t think you needed anything from me.”

Silence. Silence so deep I could hear his breath climb and catch. Somewhere behind him, my mother’s voice—shrill in a way I’d only heard when she burned the gravy—asked, “What does she mean by that?”

He swallowed audibly. “Catherine,” he said, the consonants of my full name suddenly too formal, “this isn’t funny. Your mother is beside herself. The cousins are here. You need to—”

“To what? Pull a turkey from my back pocket like a magician?” I let the pause crackle. “I placed the orders. I paid for them. I canceled them when you uninvited me. You told everyone I wasn’t coming, Dad. You also told me you didn’t need me. I finally listened.”

“I— We—” he started, then stopped, the sound of a man choking on a script whose last page had been torn out.

I could have filled the silence with absolution. I could have rescued them from the consequences of their own deceit. The old version of me would have. But that version had been laid to rest one week earlier, when I learned I had been erased from the headcount of people who matter.

“Happy Thanksgiving,” I said, and ended the call.

My cousin Hannah’s texts provided color commentary I did not ask for but did not turn away. No turkey. No pies. Your mother hasn’t come out of the bathroom. Your sister’s sobbing because she brought that guy from her office to impress him and he keeps asking if we’re doing a salad course. Uncle Jim just asked loudly if you were supposed to bring the turkey.

People are putting it together.

Three days later, my mother added her first offering to the group chat since the holiday: We really missed you on Thanksgiving. Hope we can put this behind us. An attempt at burial without the bother of a funeral.

I didn’t respond. I started walking at dusk instead—long loops through the neighborhood where Christmas lights had already begun their blinking arguments with the dark. My aunt called in that lull between dinner and dishes, when phone calls feel less like interruptions and more like invitations.

“They’re getting an earful,” Aunt Marie said. “Eleanor told your mother off in front of three people. Your father’s friend asked him what on earth he thought was more important than his own daughter. Your mother cried. Then told people you were too sensitive.” She paused, something softening in her voice. “Honey… they’re not used to being the ones who answer for things. That’s… new.”

“It doesn’t have to be new,” I said. “It just has to be true.”

My mother adjusted quickly, as she always had. Within days the alternative narrative appeared like an unflattering photo furiously untagged: Catherine is unstable. Catherine is dramatic. Catherine sabotaged Thanksgiving to hurt me. She called relatives she barely spoke to and asked them to pray, not because she believes, but because pity is a kind of religion too.

I waited until the ground was fully salted with her story before sending a single message to the family group chat.

Hey everyone—just wanted to clear up some confusion. I’m doing great. No breakdowns, no drama. It’s been an interesting holiday season, but I’m genuinely in a good place. Hope you all are, too. Wishing you a peaceful end of the year.

Impossible to twist. Impossible to argue with. The conversational equivalent of a smile that doesn’t invite a hug.

Then, because sometimes dignity looks like boldness in a better coat, I called my grandmother.

“Finally,” she said without hello. “I was wondering when you’d get tired of letting people mistake manipulation for manners.”

My grandmother—my mother’s mother—had been exiled from our holidays years ago after a fight that could’ve been avoided with an apology on either side. My mother built a new myth that my grandmother had been “difficult,” a word that is dangerous only in the mouths of people who want you to sit down.

“I want you at Christmas Eve,” I said.

“I haven’t been in that house in ten years,” she said. I could hear the smile in her voice like a light turned on in a room that had been locked. “I’ll bring the good green beans. The ones with the almonds. Your mother hates those.”

When the door opened on Christmas Eve, the room did the thing rooms do when a surprise arrives. Conversations stopped and the smell of cinnamon slid sideways as people turned. My mother froze in the doorway, smile a perfect vinyl record that just skipped. My father’s hand paused halfway to his mouth, glass missing his lips by an inch. My sister blinked, thumb mid-scroll. My brother’s eyes went wide, then—maybe this is memory lying—bright.

“Merry Christmas,” I said, unwinding my scarf, stepping aside like a stagehand revealing the star.

“Oh my,” my grandmother said, taking in the foyer like an appraiser. “It’s been so long. What lovely decorations, dear,” and she kissed my mother’s stiff cheek and stepped around her as if the war had been declared in a different house.

The dinner that followed had the tense music a person hums when they can’t remember the lyrics. My grandmother examined the stuffing with operatic interest and asked, “Is this the store-bought kind?” in a tone that somehow managed to both insult and bless. My aunt’s shoulders shook with contained laughter. My mother smiled until her gums looked like something painted on.

It’s a risky thing to bring a ghost to dinner. She touched the china the way you touch memory that’s been polished to look like inheritance and put her fork down the way a person puts down a gauntlet that looks like flatware. She had never liked the way my mother styled the table. Personally, I hadn’t either. In my mother’s hands, the runner looked like a metaphor for a life you could suffocate on.

Within days, people began to reach out from corners of the family I’d forgotten existed. Heard there was a misunderstanding. Hope you’re okay. Praying peace for you. Shocked at how you could be so cruel to your mother, frankly. The last one came from a cousin who sends bible verses with her Amazon referral link and once told me grief is selfish if you don’t hurry.

The call that mattered arrived on a Tuesday, the kind of day that’s so Tuesday you can smell the calendar.

“Hey,” my brother said. He hadn’t called me in months. “Can we talk?”

He stood in line at a coffee shop when I called him back. I could hear the hiss of steam and the murmur of people who all carried the belief their drink could be distinguished by how many adjectives it required. He didn’t start with preamble. “I don’t agree with what Mom did,” he said, words like a car pulling into a driveway he intended to stay in. “Thanksgiving was… wrong.”

I didn’t realize I’d been holding my breath until I let it out and it sounded like relief. “You don’t?”

“She told everyone you weren’t coming, then made you pay,” he said, disbelief a new taste in his mouth. “I mean—” he exhaled— “I should’ve said something. But you know how she gets.”

I knew. I have always known.

“I’m sorry,” he said, and the apology landed not on what had happened—he hadn’t done it—but on the space between us, where not speaking had allowed something to bloom that I couldn’t weed alone.

If you’ve been the scapegoat, the one onto whom the group’s shame is projected, the one who sees the lies that let everyone else keep sitting comfortably—you know what it feels like when someone finally looks at you and sees a person instead of a role. It is both liberty and grief. Liberty because you are no longer alone, grief because you see more clearly how long you’ve been.

Sunday afternoon, my mother summoned me the way monarchs summon dukes. We need to talk. In person. Six p.m. Command masquerading as concern.

My aunt said, “Just hear them out,” because she is kind and believes in closure the way some people believe in coupons—if you have enough, you’ll be wealthy.

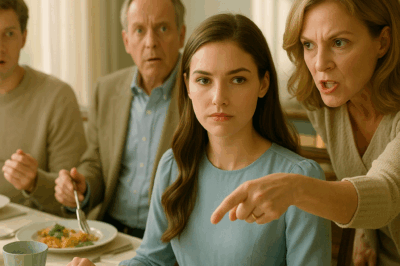

I went. The door opened and the house smelled like lamb and oranges, which is to say it smelled like a meal you remember even if they don’t want you to. My father stood by the table, arms crossed, posture his favorite weapon. My mother sat at the head like a queen who hates democracy. My sister was there, four inches of her forehead visible over her phone. My brother stood back, hands in his pockets, playing with his keys, a nervous tic he learned when he was young and learned to hold.

“Do you have any idea what you’ve done?” my mother asked, the line rehearsed sufficiently to sound like belief.

“Which part are you mad about?” I asked. “The turkey, the Christmas surprise, or the fact that people don’t believe your story?”

“Dramatic,” she said, as if she’d had to carry a soaking wet rug across town while I sipped tea.

My father tried to keep his voice level and failed. “You embarrassed your mother.”

“She embarrassed herself,” I said, and it’s an unkind sentence, but unkindness sometimes has to be held up like a mirror. “I just removed the curtain.”

“We never meant to exclude you,” my mother said, defaulting to passive voice, her favorite grammatical tool. “We just thought it would be easier. And then you had to—”

“Had to?” I laughed, humor with an edge sharp enough to cut without warning. “You told everyone I wasn’t invited. You let me pay for the meal. You let me plan it because you wanted the attention of the result with none of the responsibility for the means. And when it backfired, you called the family and told them I was mentally unstable because you were embarrassed to be seen as wrong.”

Silence. The room contained the sound of chairs being turned.

“I was embarrassed,” she blurted, and the room moved. She blinked, surprised even by the truth coming out of her mouth. “I—I didn’t know what to say when people asked why you weren’t there. I couldn’t stand everyone looking at me like I was the bad guy.”

“So you made me the bad guy,” I finished for her. Her jaw tightened like a person who hates that the truth ruins the scene she had planned.

“No one should have to live like that,” my grandmother had told me three nights earlier, pulling tinfoil over the green beans. “Bending yourself into a shape that looks like forgiveness when the other person hasn’t changed the thing you’re forgiving them for.”

My father stared at the floor. “Maybe we should have handled it better.” The crumbs of a man who thought charity was the same as contrition.

My sister mumbled, almost to herself, “We all should’ve said something,” and I felt a surge of compassion for the version of her that might exist someday.

“I’m done,” I said, standing. “I don’t need an apology. I don’t think you know what one is. I do need you to know that I will not be the person who makes your bad decisions look like a community service project anymore.”

My mother flinched like that was a slap. She spiraled through the five-stages-of-someone-else’s-grief in under a minute: denial, bargaining, instructing, accusing, and then—because she always ends up where she started—image management. “What am I supposed to tell people?”

“That the truth was at your house, and you wouldn’t let her in,” I said, and walked out.

On the porch, the cold bit my cheeks in a way that felt like a friend reminding me I was alive.

The weeks that followed were quieter than I expected. My mother texted vague apologies with typos I had never seen her make. Can we move past this—no question mark, which told me everything. I didn’t respond. I stopped feeling responsible for being the glue that melts and holds.

But the space didn’t stay empty. My brother called to ask about a recipe for a thing he remembered hurt the way a memory hurts when you realize it didn’t include you. He asked if we could do coffee again, just us. We did. He cried. I cried. We stayed until the barista flipped the chairs and mopped around us.

I built a new table. Not metaphorically at first. Physically. I found a slab of cherry at a store that smells like sawdust and possibility and I sanded it until my arms ached. My grandmother showed me how to oil it until the grain looked like a story that had always been there. On the third Saturday of December, I hosted a small dinner for people who had chosen me. No one commented on the runner. No one left early because the real event was at someone else’s house. My brother brought wine. My aunt brought laughter. My grandmother brought politics. I brought the thing I should have always kept: boundaries served on plates.

For New Year’s, I sent a single message to the family chat. May your tables be full, and may you notice who fills them.

I don’t know what next Thanksgiving will look like. Maybe my mother will find a therapist who knows the difference between contrition and control. Maybe my father will learn that passivity is not neutrality. Maybe my sister will learn that silence sides with power. Maybe none of that will happen.

What I do know is that I won’t sit at tables that require me to starve so someone else can feel full. If you’ve read this far, perhaps that is your work, too: to ask whether the role you’ve been handed is a seat or a leash. To remember that sometimes the empty chair is not a tragedy; it’s the first visible sign of a boundary that finally learned to hold.

Thanksgiving has always been sacred in my family. It still is. It’s just that now I know who I’m thanking.

Part Two

January made a habit of arriving too quietly in our town, slipping the world into colder light and making everyone talk softer. In that lull after the holidays—the week when most people return gifts and return to themselves—I started walking after dinner. My neighborhood lifted its decorations in slow motion: first the inflatable snowmen sagged like sailors after a storm, then the reindeer buckled, and finally the lights went dark one string at a time, like good intentions. I walked and let my body remember the suggestion of ease.

I didn’t block anyone. Not my mother, not my father, not the machine of updates that wraps every branch of a family tree. I didn’t answer either. Silence can be violence when used to avoid. In my case, it was simply neutral air where the fire had been.

It took a week for the next narrative to roll in like a fog nobody asked for: Catherine is unstable. Catherine sabotaged Thanksgiving to hurt her mother. Catherine brought her grandmother to Christmas to cause drama—as if an old woman with her own keys could be smuggled like contraband. My mother had learned to weaponize worry decades ago. She called people she hadn’t called in years to tell them to pray for me. Pity is the plenty you plant when you run out of the truth.

I didn’t try to persuade anyone otherwise; persuasion had been my part in the family play for too long. Instead I texted the only thing that couldn’t be misquoted:

Hey everyone, just wanted to clear up some confusion. I’m doing great. No breakdowns, no drama. It’s been an interesting holiday season, but I’m genuinely in a good place. Hope you all are, too. Wishing you a peaceful end of the year.

It felt like putting a hand to a bell to stop vibrations. The quiet that followed had a new shape.

In January, I bought wood. There’s a store across town that smells like prayer: sawdust, oil, and the private satisfaction of making something that will outlast you. I found a slab of cherry with a grain like a weather map. The man behind the counter ran his palm over it in a way that made me wish people touched each other with that kind of reverence. I built a table in my garage after work, wearing my father’s old flannel and my own stubbornness. My grandmother came on Saturdays with a thermos of coffee and a list of opinions. She told me to sand with the patience of someone who’s forgiven slowly. She showed me how oil wakes up wood.

“You’ll host here,” she said, running her knuckle along the edge until the shine matched the light. “You’ll decide who sees you eat.”

When the table was finished, I set one place and ate takeout lo mein off the good plate. I put the fortune in my pocket. It said Your luck will happen by midnight. It didn’t. But when I put on my coat the next morning, the paper fell and made me laugh at the way we find prophecies when we need them.

My aunt—bless every aunt who becomes an exit door in a house full of locked rooms—called every Sunday. She told me who had said what, who had stopped agreeing with my mother’s version, whose silence had shifted into questions. “Your brother is thinking out loud,” she said in February, her voice bright with something I didn’t trust enough to name yet. “He asked your father when the last time was that he apologized to someone directly without adding ‘but.’”

The first time my brother invited me to coffee, it was snowing. The second time, it wasn’t. Both times, his hands wrapped around the paper cup like a person trying to remember how to warm himself. The second time, he cried and didn’t apologize for it, which felt like its own apology. “I spent thirty years translating Mom,” he said, staring at a piece of foam like it might answer back. “I didn’t realize there was another language.”

I told him a thing my therapist told me—therapists being midwives for births like these—that guilt is a compass that only points to the past. “Use it,” she’d said, “to orient yourself enough to move forward without building a house there.”

He nodded. We walked the long way back to our cars, the kind of long that allows old narratives to stretch and snap where they’re weak. We didn’t fix thirty years; we made a dent.

My father did what men like my father do when the story cracks. He puttered. He raked the same patch of leaves three times and called it progress. He called me twice and left a voicemail with a shape like a shrug. “Your mother’s been unwell,” he said, as if emotion were a fever that excused behavior. I didn’t call back. The third time he dialed, my phone put his face beside a ringing sound that made my teeth ache. I answered because people like me always answer. “I don’t know what you were trying to prove,” he said without preamble and with the weary authority of a man whose job had always been to stand between a woman and the feeling of being wrong. “But you embarrassed your mother.”

“That sentence is a cathedral to everything that’s broken here,” I said before I could swallow it. I heard him inhale. “You should have said something if you had a problem,” he tried.

“I did,” I said. “For a decade.”

“It wasn’t that big a deal,” he said, and whenever that phrase was brought out in our home it meant this matters to you and thus cannot be allowed to matter.

“If it weren’t a big deal,” I asked, “why are you calling me about it weeks later?”

He couldn’t figure out where to put that question, which is how questions work when they require a person to stand somewhere they haven’t prepared a speech.

I ended the call before I started comforting him. Then I stood in the kitchen and cried—not because I wanted him to be different, though I did, but because the part of me that keeps inventory had to adjust the numbers and it hurt.

February made a habit of pretending to be April. Crocuses pushed up with irritated bravery. I took soup to an elderly neighbor who always called me “dearie” as if names were trinkets we shouldn’t wear on weekdays. She invited me in and told me about the year her daughter left for California without saying goodbye properly. “You can break a heart and still be good,” she said, ladling more soup into my thermos. “But don’t break your own trying to feed someone who insults your cooking.”

By March, my mother had made two attempts at reconciliation: one text with five sentences and four typos (Can we move past this—no question mark), and one voicemail that cut off as she reached the apology, which felt on brand. My aunt said she’d been quiet at book club, a place where she had always been loud. My grandmother delivered the first actual news: “She started therapy,” she said, trying to sound bored and not succeeding. “With a real one, not those Facebook groups where they excuse each other’s bad behaviors by calling them boundaries.”

“Good,” I said, and meant it, the way you mean it when someone decides to get up off the floor they insist is a chair.

April’s daffodils made a show of being shocked that color existed. I took my grandmother to the nursery to buy herbs. She put her wrinkled hand in the basil like a person blessing water. She rested her palm on the sage like you rest your hand on a person’s head when you want to say you are more than the thing you are learning to be. That night we ate pasta with butter and crisped sage leaves and she asked me if I planned to host Easter. “No,” I said. “Not this year. I am trying to loosen my grip on performative second chances.”

She snorted. “They don’t know who they screwed with.”

I didn’t host anything that spring. I went to movies alone and laughed at the wrong parts. I took myself to dinner with a book and tipped like I remembered the busser’s name even when I didn’t. I built a bench for the porch. I let my body learn how to sit on something I made and call it rest.

In June, my mother asked to meet. The text wasn’t dramatic. Just Coffee? and a time and a place that wasn’t a trap. I chose a cafe with good air and a view of people who looked like they might interrupt if voices rose. My mother arrived exactly on time with her hair softer than I’d seen it and her makeup imperfect in a way that suggested shaking. I had rehearsed four versions of this conversation, three that ended with me walking out and one that ended with me crying. I left them in the car.

She took off her coat and hung it on the back of her chair like a white flag.

“I’ve been talking to someone,” she said, and I didn’t roll my eyes. “I told her I was embarrassed,” she said, and I didn’t correct her word choice. “I told her that my mother—” she stopped like a runner who just realized the track is longer than advertised— “your grandmother used embarrassment as a leash. I thought if people saw me as wrong it meant I was unlovable. So I made you wrong because I couldn’t bear the weight of it.” She lifted her eyes and put them on mine. “It wasn’t fair. I am sorry.”

It wasn’t perfect. It wasn’t the long list of specific things she’d done stitched into a confession we could frame. But it was different. My mother doesn’t do wrong. And there she was, saying a thing that might be the first rung on the ladder down from a position nobody asked her to hold.

“I need you to understand something,” I said, and the way her mouth flicked told me she had expected that sentence to end with what you did to me. “I won’t come to holidays you invite me to as decoration. I won’t pay for meals I’m not allowed to eat. I won’t sit quietly while you fix your image with my silence.”

She nodded—one of those nods people do when they’re agreeing to something they only half believe in because it keeps the peace. Then she reached into her bag and took out an envelope. “I wrote letters,” she said, which was such a private sentence I didn’t breathe for a second. “To Aunt Marie. To your grandmother. To your brother. To you.” She pushed mine across the table.

I didn’t open it there. I am proud of that.

We talked about vegetables for a while, and work, and the price of eggs, and the dog my sister’s partner had brought into the family that my mother said she didn’t like until she realized he could catch treats midair. We didn’t solve anything. We didn’t try to decorate the unsolved with niceness. We said we would try again, and that was enough to end the coffee without a fight.

I opened the letter on my porch that night, the new bench holding my weight like a promise. It was three pages. It contained sentences I had never heard from her: I blamed you because you were safest. I told my friends you were unstable because I was afraid they would think I was a bad mother if I told them that I excluded you. I’m sorry. I will correct the story when I hear it told wrong. The last line made my ribs hurt: I want to be someone our grandchildren will not have to recover from.

July offered relief in the form of bushels. I canned tomatoes like my grandmother taught me—bath, lids, the click that sounds like agreement. My brother wrote a group text to just the three of us—me, him, and the grandmother who had stopped apologizing for being inconvenient. Can we do Sunday dinners? he asked. Pizza on your table, Catherine? And I surprised myself by saying yes, because imitation is sometimes the sincerest form of family.

They came every other Sunday after that. The rhythm of it held us: my grandmother with her green beans and opinions; my brother with his new habit of asking instead of assuming; me with a pitcher of water and a new commitment to leaving when I was tired without writing a speech first. We did a jigsaw puzzle that took four Sundays and had three pieces missing, which felt like an honest metaphor we could all stomach.

My father started walking in the mornings. He sent me pictures of his socks and the river; you never know where grace is going to come from. Once, in September, he called and didn’t mention my mother until six minutes in. “I raked the other side today,” he said, and for the first time in a year his voice sounded like a porch we might someday sit on when the weather remembers how.

“Thank you for choosing a sentence that isn’t about her,” I said, and he laughed like he had found a thing in his pocket that he didn’t realize he missed.

October arrived and with it the creep of other people’s gratitude lists. I hate that impulse—the way people perform gratitude like a talent show—but I made one in my head anyway: my grandmother’s fast heart, my brother’s late learning, my aunt’s persisted loyalty, my hands that build.

In November, an email came from my mother. No gifs. No italics. Just a subject line: Thanksgiving. The body of the email was shorter than the apology letter and felt less like a plea than a plan. We would like to come to your house, she wrote, and I read it three times to be sure she had used the plural that included my father and not the royal one she’s used for years. If you will have us. We understand if you won’t.

I printed it and taped it to the fridge and walked around it for a week. I took it down. I put it back up. I talked to my therapist, who asked what I would need to make a yes not become a no halfway through the evening.

I wrote a list. Then I wrote an email.

If you come, you come by the rules of my house:

1. No one is to mention last year unless it is to acknowledge harm without needing a response.

2. The runner stays in the drawer.

3. Everyone sits where they’re told. If you don’t like your seat, you get up and go home without a monologue.

4. No triangulation. If you have something to say to someone, you say it to them with a napkin in your lap.

5. You bring your apology with you or you don’t come.

I read the email three times and waited for regret. It didn’t arrive. The only reply that did was five minutes later: We understand. We will be there at two. I’ll bring the Brussels sprouts and my apology. It was signed, for the first time in a year, Mom.

I expected to be nervous on the day of. I wasn’t. It felt like the day before a test you’re ready for not because you like tests but because you cleaned out your backpack and the pencils are sharp. My grandmother came at ten with a pie I didn’t ask for and a story about someone at the grocery store who told her to smile. She said, “I told him I smile when I feel like it, not when I’m told,” and we shouted “amen” in the kitchen like the kitchen had always been the church.

At 1:40, my brother texted parking, which meant he was pacing outside to call me if he needed a lifeline. The doorbell rang at 1:58. Of course it did.

I opened it to my parents on the porch. My mother held out a casserole and something softer in her face. My father held out tulips in October because he never did figure out the calendar of flowers. “Welcome,” I said, and meant it in a way that made my knees feel like new wood again.

We didn’t hug. We took coats. My grandmother stood at the arch between rooms like a border crossing. “Hello, Ellen,” she said, using my mother’s full name. The last time she had used it, it had been underlined by a slammed door. “I’ve been waiting a long time to tell you the green beans were always good and the runner was always ugly.”

Something in my mother’s face untensed—some muscle in her jaw that had done the heavy lifting of pretending for forty years sagged with relief and then gathered itself up for something else. She nodded. “You were right,” she said to her mother like a person returning an overdue library book. “About both.”

I had not prepared for that moment and it undid me in the best way. We fed each other. We held the silence as deliberately as the serving spoons. My mother tried once—instinct is a busy thing—to move a fork to the right of where I had placed it, and I looked at her and said, “Not in this house,” and she laughed and withdrew her hand. My father went to carve the turkey and then stepped back and asked, “Is this yours to do?” the way a person would ask in a country where they don’t speak much of the language yet and don’t want to offend.

We ate. We passed. We didn’t perform. When my mother cleared her throat—there is always a throat-clearing with women who were given dentures where their vocal cords should have gone—I carried the pie to the table and set it down between us and put the knife beside it the way you put down a choice.

“I’m sorry,” she said, and the room didn’t move lest it startle the apology. “For last year. For the years before it where I told stories about you when the stories about me would have been braver.” She swallowed. “I’m sorry for calling you dramatic when you were being honest and difficult when you were being alive.” She put her hand on the table, maybe as an anchor. “I will make it right when I hear it wrong out there.”

“That’s the only apology I needed,” I said. “The one you keep saying when I’m not here.”

We didn’t hug then either. We ate pie, and my grandmother declared it “better than store-bought when the store remembers how,” and my father knocked his fork against his plate in a private rhythm that told me his heart had learned a new song.

Later, after we’d done the dishes—the kind of done where you dry each plate until it squeaks because you want to believe that difficulty can be rendered clean with elbow grease—my mother stood at the doorway looking at the table. “I hated that runner,” she said. I laughed so hard I had to sit down.

She looked at me and then looked at the bench and then looked at me again. “You built this,” she said and it wasn’t a question.

“Yes,” I said.

“It’s beautiful,” she said, and because she has always used beauty to punish, the word felt like an absolution. I didn’t owe her that forgiveness. But I took the part that was mine.

They left just before the light folded itself into evening. On the porch, my father put his hand on my shoulder and didn’t squeeze or direct. He just let it rest there like a bookmark that says I will be back. My mother stood at the bottom of the steps and turned back. “We’ll see you in two weeks,” she said. She didn’t ask. She didn’t command. She named.

When the door closed, my grandmother sat at the table and put both hands flat on the wood like a woman blessing a boat. “We ate without lying,” she said. “That’s all I ever wanted.”

There’s a thing that happens when people defend you in rooms you’re not in. You hear about it secondhand. In December, my aunt sent me a voice memo of my mother on the phone with Eleanor, saying “I was wrong,” and then catching herself and saying it again without the voice she uses when she rehearses for an audience. In January, my cousin Hannah texted, Your mother cried at church, and then added, The real kind, not the pageant kind. In February, my brother sent me a picture of my mother and grandmother at the nursery pointing at rosemary, and I sat down on the bench and let myself cry for everything we had missed and yet somehow found.

Does healing happen like a movie montage? No. It happens like learning to sleep after years of not being allowed to without the light on. Slow. Screechy. With blankets that sometimes feel like old scripts you have to throw off. But it happens.

On the one-year mark of the Thanksgiving I didn’t attend, my brother and I walked to the park that looks over the river. The water moved, indifferent as ever. The stones remained. He picked up a smooth one and turned it over like a worry he didn’t need anymore. “Do you miss it?” he asked. “The old version?”

Sometimes. The version where I was useful without being loved has a gravitational pull. There is relief in being necessary. There is also a boundary you must build when you realize you deserve to be wanted, not just needed.

We stood a long time. Then we went back to my house, sat at my table, and ate leftover pie like people who had run a race they didn’t train for but finished anyway.

I don’t know how your story ends. Maybe you will not be invited to Thanksgiving again. Maybe you will not pay for turkeys you are not allowed to eat. Maybe you will bring your grandmother to Christmas and feel like a person who opened a door wider than your mother thought she could stand. Maybe you will decline to take on the role that felt like a calling simply because it was an assignment.

This is how mine ends this year: I set the table with mismatched plates because they all have stories and I don’t believe in quieting them. I left the runner in the drawer. I put the carving knife where it belonged. When I went to pick up the turkey, the butcher smiled. “Same as last year?” he asked.

“Not at all,” I said, and the words tasted better than gravy.

END!

News

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street… CH2

My Father Said I’d Never Be ‘The Bright One’ — Then His Friends Saw My Face On The Wall Street……

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My ‘Affairs’ At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… CH2

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My “Affairs” At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… Part One The first…

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything. h2

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything Part One…

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… ch2

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load