One Night, My Brother Beat Me With a Belt Until I Collapsed—Mom Said “Be Grateful We Feed You”

Part 1

My name is Emily Carter. I’m thirty-two now, but the night that still wakes me—the one that cleaved my life into a before and an after—happened when I had just turned twenty. If I close my eyes I can still hear the belt cutting the air, a heartbeat of silence before leather found skin. I can still feel the way my knees failed me, how the floor seemed to rear up to meet my cheek. It wasn’t an accident. It wasn’t “discipline.” It was an assault carried out by my brother, Mark, while my mother watched from the doorway and said, with the coolness of someone discussing the weather: “Be grateful we feed you.”

People like to imagine violence arrives like thunder on a clear day: sudden, shocking, singular. In our house, it crept in like water seeping through hairline cracks, invisible until the foundation gave way. The belt was only the final form of a control that had been tightening for years.

I used to hide myself in notebooks—dreams sketched in the margins of homework, doorways to a life beyond the Carter house. The library became my place to breathe. I wrote about dorm rooms I’d never seen, professors whose names I invented, a desk by a window that belonged to me. Mark learned to hate those notebooks. He called them poison, then “nonsense,” then “lies you tell yourself because you think you’re better than us”—a script he inherited from our mother as neatly as you inherit the shape of a jaw.

The night everything exploded began like dozens before it: quiet house, bad air. I was at my small desk, college application forms spread out, my acceptance letter from a university in another state folded beneath a notebook like a secret talisman. When Mark shouldered through my door, the room changed temperature. He smelled like beer and anger. He didn’t greet me. He didn’t ask. His hand darted out and took what I had guarded with my life.

“You think you can leave?” he hissed after reading the letter. “You think you can walk away from this family?”

“Yes,” I said, and surprised both of us. My voice trembled but held. “I deserve a chance at my own life. Dad would have wanted me to go.”

At the mention of our father, Mark’s face hardened. Our father, David, had been a construction worker who came home every night smelling of sawdust and sweat, lifting me onto his shoulders so I could “touch the stars” on the walk from the car to the house. He died when I was eight—an accident on the job—and the center fell out of our lives. For a while grief softened us. My mother, Linda, worked double shifts at the diner and fell asleep at the kitchen table with grocery lists stuck to her cheek. We were a team then, the two of us.

But grief calcified in her. By the time I was twelve, she had retrained herself to value appearance over truth. “We don’t air laundry,” she would say, even when the house smelled like bleach and fear. She began calling Mark “the man of the house.” At first it sounded like a compliment she needed to say to get through the day. He made it a title. “Listen to your brother,” she’d tell me across the room. He absorbed the job description and then rewrote it: what shows I could watch, what I could wear, how long I could be in the bathroom. “You’re provoking him,” she’d say when he slammed my door open. “He’s only trying to protect you. Be grateful you have a roof. Be grateful we feed you.” That last sentence grew fangs. It sank into the marrow of every conversation until gratitude meant silence and silence meant survival.

I learned to live small. I kept a second notebook at the bottom of my bag, pages pressed flat by a library card. I joined after-school clubs not because I loved yearbook or debate, but because they let me linger under fluorescent lights a little longer before heading home. At home I listened for footsteps and translated moods into weather forecasts: low pressure, high risk. When I was shoved, I recorded the shape of the bruise in my journal—“left forearm, oval, purple at the edges”—as if cataloging it might make me real to myself. At the time I didn’t call it evidence. It was only a mirror the house couldn’t steal.

Mark grew bolder as my plans grew clearer. He rifled through my drawers like a customs officer. He read my texts and demanded I account for names he didn’t recognize. He tore up essays mid-sentence, the blade of the paper snagging against his fingers as if even the stationery wanted to fight him. Our mother learned to stand in doorways like a sentry. “He gets stressed,” she’d say. “You need to stop provoking your brother.”

I saved money the way you save air in a sinking car. Part-time jobs at the library and the cafe added up to crumpled bills I tucked inside a hollowed-out book from a thrift store, its pages glued together with Elmer’s and stubbornness. I recorded fights on a cheap tape recorder I found at a yard sale and hid in a cereal box. I snapped photos of bruises in the bathroom mirror with the sound off. I told myself I was only keeping a record for me, a private confirmation that I wasn’t “too sensitive,” that what was happening was happening. Survival wore the outfit of documentation.

By nineteen, control had replaced conversation. Mark decided when the lights should go out and when they should come on; he decided whether I had “earned” dinner. If I came home late from the library, he’d lock the door and make me plead on the porch while a neighbor’s eye flickered behind a curtain. If I looked happy, my mother’s voice could find me across the room: “Why are you smiling?” If I sighed too loud: “What’s your problem?”

And still, a stubborn part of me—the part that remembered my father’s warm hands and the way he never raised his voice—kept whispering that none of this was normal. That whisper sustained me as I sent scholarship forms from a library computer, logging out twice, clearing history three times. As I stuffed my acceptance letter beneath a notebook. As I allowed myself to imagine a desk by a window that faced east.

So when Mark yanked the letter free that night and I said “Yes,” I wasn’t only answering his question. I was answering myself.

He slid his belt out through the loops in one indifferent motion. The sound lives in my bones. The first strike buckled my breath. The second knocked me sideways. By the third and fourth, the pain had blurred into a long scream that made my throat raw. I tried to block my face; the belt curled around my forearm and raised a welt that came up like a map. Somewhere under the noise, under the hot sting and the cold boards, I heard another sound: the soft rasp of my bedroom door against the frame as it opened wider. My mother leaned her shoulder into the wood and watched. “Mom,” I cried. “Please help me.”

She tilted her head—almost curious—and said, as if offering a life lesson, “Be grateful we feed you.”

Something worse than pain opened in me. Something old and necessary broke. Mark wrapped the belt around his hand to shorten it and swung again. When I tried to stand, my legs forgot the instructions. I fell. My cheek found the place on the floor where varnish had worn away. The room narrowed to a tunnel. He yanked me up by the arm until my shoulder burned white. He shoved me against the wall so hard my vision fizzed at the edges. When the belt came down again across my ribs, I heard a pop inside me and couldn’t find air. The last thing I knew before the dark arrived was his voice, low and satisfied: “You’ll never leave.”

When light returned, it came in slices: a harsh rectangle on the ceiling; the green bar of a heart monitor rising and falling to prove I was still here. I tasted metal. Pain planted flags everywhere. A nurse’s voice, firm and kind, told me where I was. Safe. The word felt theoretical. The machines believed it more than I did.

“You have two cracked ribs,” the doctor—Dr. Patel—said softly. “Significant bruising. Signs of prior trauma.” The last phrase punctured something in me. Prior trauma. The history I had written down in secret had announced itself on my body.

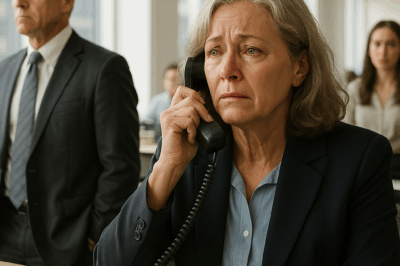

A police officer came later, his voice careful. “Emily, can you tell us what happened?”

“My brother,” I said, and hearing myself say it made it truer than all the journals. “He beat me with a belt. My mother watched.”

“Your neighbor called,” he said. “They heard screaming. Officers found you unconscious.” He paused. “We’ve taken your brother into custody. Your mother is under investigation.”

A social worker named Karen arrived after the shift change, a file under her arm, a steadying hand on the rail of my bed. “You’re brave,” she said in a tone that didn’t demand modesty. “This is the beginning of a process, not the end. There will be statements. There may be a trial. We will help. Are you willing to cooperate?”

If fear is a weight, relief is the moment you realize you’re strong enough to carry it. I thought of belts and floors, of notebooks snatched and torn, of my mother’s thin mouth forming the words “Be grateful we feed you.” I nodded. “Yes.”

The hospital became a strange kind of refuge. Nurses wrapped ribs and checked vitals and traded jokes at 3 a.m. that made the hallway feel human again. Karen explained things between blood draws. The police photographed the ladder of welts up my arm, the constellation of bruises on my back. They collected my journals and the little recorder from the cereal box, appeared genuinely grateful as if I had handed them a rare book. A neighbor turned over a cell phone audio clip from that night—my screams, Mark’s voice. Evidence multiplied until the story no longer fit back inside the house.

News filtered in on paperwork and quiet visits. Mark was being held without bail. Linda had been charged with child endangerment. She had told the police she “froze” and “didn’t know what to do,” but the neighbors’ testimonies—years of shouting, slammed doors, my flinches—built a timeline that didn’t care about her excuses. A line from Dr. Patel stuck with me: “Trauma isn’t the thing that happens to you; it’s what happens inside you because of the thing.” I added it to my journal, the first entry I had written without hiding in years.

I cried often, and in the way you do when tears are finally allowed to arrive, they were ungraceful, inconvenient, necessary. I cried for the father I lost, for the mother I needed, for the girl who learned to take up less space to avoid impact. But every morning I woke up in a bed that didn’t require me to listen for footsteps, and that counted, too.

Three months later, my ribs still tender under my blouse, I stood in front of a courthouse that smelled like polished wood and coffee. Reporters clicked their cameras; people talked in the low murmur reserved for waiting rooms and church. Karen put a hand on my shoulder. “You’re ready,” she said, as if readiness were an outfit I could put on. I wasn’t sure. But I nodded.

Inside, Mark wore a suit that made him look like he belonged to a different species. He kept his jaw rigid and his eyes on some point over my head. Linda sat beside him with her hair neat and her mouth set, staring at the table as if she might find a plan in the grain. Seeing them together made my breath hitch, but then Ms. Daniels—the prosecutor—leaned toward me and said, matter-of-factly, “We have everything we need: your testimony, medical reports, photographs, your journals, the recording, the neighbors’ statements. Tell the truth. Let the evidence do its work.”

When Ms. Daniels stood to give her opening, she didn’t raise her voice. “This is not discipline,” she said evenly. “This is prolonged abuse. This is a brother who believed he had the right to control and harm his sister, supported by a mother who chose silence over protection.”

Mark’s attorney stood like he was auditioning for a television show and tried to rewrite me: unstable, hysterical, dramatic, resentful. He called my journals “creative writing.” He called my dreams “delusions.” He called Linda “a struggling single mother doing her best.” His tone was oil on a brittle fire. I gripped the bench and waited for my turn.

On the stand, my voice shook at first. I stared at the corner of the courtroom until the shapes stopped being people and became furniture. Then I breathed and told the story the way I had written it in my journals—in order, with dates where I had them, with details I could verify: the particular shine of the belt buckle, the phrase “Be grateful we feed you,” the hollowed-out book, the tape recorder in the cereal box, the bruise like a thumbprint above my elbow on the tenth of October. When Ms. Daniels played the neighbor’s recording, the room shifted. Hearing my own scream in that clean space made something inside me lean against the rail for balance. I kept talking.

Under cross-examination the defense attorney tried to tangle me with speed, with insinuations that looped back on themselves, with questions designed to make me doubt my own sentences. “You resented your brother, didn’t you? You fabricated entries? This is all to justify leaving, isn’t it?” I answered in the rhythm I learned writing under pressure: one sentence at a time. “I resented the abuse.” “I wrote what happened so I wouldn’t forget the truth.” “I wanted to leave because I deserved to live without fear.” He raised his voice; I kept mine steady. Every answer felt like placing a brick on a wall that could finally hold weight.

When Linda took the stand, she tried to dress helplessness as innocence. She said she had “frozen,” that she didn’t know how to stop a son who was “so upset,” that she had “done her best.” Ms. Daniels let the sentences settle and then asked, with surgical calm, “Did you ever say to your daughter, ‘Be grateful we feed you’?” Silence stretched. Then, a whisper: “Yes.” “Did you witness Mark strike Emily and choose not to intervene?” Linda stared at the table long enough for the wood to absorb the heat. Then she nodded. The jury watched. Truth can be slow, but when it stands up, it tends to stay standing.

Neighbors testified about years of shouting and the sound of a belt slapping air. A woman down the street talked about seeing me in the summer with bruises I hid under long sleeves. Dr. Patel explained the injuries, pointed to diagrams that made my ribs look like architecture, described how the welts lay where a belt would lay. The evidence built itself like a careful house.

The jury was out for three hours. They returned with words I will never forget: guilty of aggravated assault for Mark; guilty of child endangerment for Linda. At sentencing two weeks later, the judge looked at them the way a person looks at vandalism. “Family bonds were twisted into weapons,” she said. “This court is obligated to untwist them.” She sent Mark to prison for twelve years and Linda for three, with counseling mandated on release. As they were led away, Mark’s eyes stayed hard, but Linda’s shoulders slumped as if the weight had finally registered.

I walked out of the courthouse into a light that felt like intention. The air tasted different. My body still hurt. My sleep was ragged. But something in me—something that had been crouched and alert for so long—sat down.

Part 2

Freedom didn’t arrive with trumpets; it arrived with a to-do list. I needed a place to live that didn’t know my footsteps, a job that wouldn’t ask me to explain my scars, the kind of help that doesn’t call itself help because it understands the cost of needing it. Karen found me a spot in a transitional housing program where the doors locked from the inside and the staff learned my name before they learned my story. Dr. Harris, my therapist, had silver streaks in her hair and a voice that made honesty feel like a resource you had in storage.

“Trauma isn’t only what happened,” she told me in our first session. “It’s what stayed. We won’t try to erase it. We’ll help you carry it differently.”

For months my nights belonged to memories—the belt sound replayed, the doorway with my mother leaning into it like a portrait—but mornings grew their own rituals. Coffee. A walk around the block. A line or two in a journal that didn’t need to hide. “I am not what was done to me.” “My body is mine.” “I am building a life where my voice can live.” On bad days I lit a candle and wrote anyway. On better days I remembered to stretch before I got out of bed so my ribs didn’t scold me for trying to be hopeful too fast.

Physical therapy made me make friends with my breath. “We rebuild from the inside out,” the PT said, setting a timer while I lifted an arm a centimeter higher than last time. “Small victories count as victories.” I learned to celebrate incremental miracles: a deeper inhale; a night without waking; an afternoon where I laughed and didn’t immediately look around for punishment.

A support group became a language I could speak without translating. The first time I walked into the room, I held my nervous system like a cat I was hoping not to startle. A woman with a scar above her eyebrow made room beside her and said, simply, “Hi.” We traded stories like bandages, sharing what we had needed when the wound was fresh. There was relief in the chorus: Me too doesn’t fix anything, but it keeps a person from drowning alone.

I enrolled in community college because I loved the idea of being asked what I thought instead of being told what I was. Psychology felt like learning the map of a city I’d been lost in. Creative writing gave me a place to put the heat that rose in my throat when I remembered my mother’s sentence. A professor wrote at the bottom of an essay: Your pages help people breathe. I taped it to the inside of a notebook and read it when sleep refused.

Healing didn’t move in a straight line. On the anniversary of the night with the belt, my chest tightened at a bus driver’s voice and my ribs ached even though they had healed. Dr. Harris taught me to name a trigger out loud—“This is a memory, not a command”—and to drop my shoulders on purpose when fear climbed my spine. When I felt guilt for feeling joy, she said, “Pleasure is not a betrayal of your past.” When I told her I was afraid of becoming hard, she smiled. “You are proof that strength and gentleness can share a house.”

I started volunteering at a domestic violence shelter on Thursday nights. At first, I ladled soup and kept my eyes on the edges of the room so I wouldn’t accidentally catch someone’s grief head-on. Then I learned that quietly folding donated clothes counted as prayer. That reading a story to a child whose mother was filling out forms could rearrange a person’s lungs. That sometimes the most useful sentence is “I believe you,” offered without a follow-up question. The work made me feel like I was paying a debt to the universe that no one had sent a bill for but that I owed anyway.

Between classes and shifts, I wrote. Essays at the kitchen table of my little apartment, poems on bus rides, letters to my younger self I would never send. Karen encouraged me to submit a piece to a community center zine. When they asked me to speak at a fundraiser, I said yes and then shook so hard my hands blurred. I stood on a small stage and told the truth I had practiced telling only to myself: “My brother beat me with a belt and my mother told me to be grateful. For years I stayed quiet because silence seemed safer. Breaking it felt like jumping into winter water. But on the other side of that cold, there is air.” People stood up. Some cried. Some clapped hard, the way you clap when you want your hands to do the work your mouth cannot.

From there, there were more microphones. A high school assembly. A college panel. A training for hospital staff about how not to ask questions that feel like accusations. I led writing workshops at the shelter. “You don’t owe anyone your story,” I told the group. “But if you want it back, one sentence at a time will help.” Pens moved. Shoulders dropped a centimeter. Hope wrote itself in quick, messy lines that no one graded.

Two years after the trial, I walked across another stage in a cap and gown, community college diploma in one hand, transfer acceptance in the other. I sobbed in the bathroom afterward because I had not imagined my body would ever stand at a podium for anything other than defense. I transferred into a social work program with a focus on trauma. Some days it felt like opening an old bruise on purpose. Most days it felt like learning how to hand someone a map that said, Here is a way out.

I reconnected with my aunt, who had moved across state lines when I was ten and stopped visiting when our house began to bite. She called after the verdict. “I’m sorry,” she said as soon as I answered. “I should have been there. I should have asked more questions.” When she came to see me, she cried in my kitchen and brought my father back with stories I’d never heard: how he used to make pancakes shaped like letters; how he kept my kindergarten drawing in his lunchbox until oil stained the corners. We made tea and put his memory where it belonged—inside my life, not outside of it like a museum exhibit.

I learned other practical things, too. How to budget without apologizing to the total. How to tell a landlord I wanted the lock changed and not justify why. How to choose friends who texted Home safe? instead of Where were you? I learned what quiet felt like when it wasn’t a threat. I bought a lamp because it threw warm light against a wall and made my living room look like it forgave me.

Healing took my faith apart and put it back together with different screws. As a child I had prayed the way a drowning person talks to air. As an adult I learned to call faith by quieter names: breath; candle; the soft authority of my own voice. I lit tea lights on hard anniversaries and said aloud, “I survived.” I wrote the names of people who had helped me on sticky notes and stuck them to the underside of a shelf like a secret altar. Gratitude, I discovered, does not belong to the person who said “Be grateful we feed you.” It belongs to the person who handed you a glass of water and stayed while you drank it.

I kept track of legal updates because closure prefers paperwork. Linda was released early for good behavior. Word came through a cousin that she had started counseling. I didn’t know if the effort was sincere or strategic. I didn’t build my day around it. I realized that when I pictured her, I didn’t feel rage; I felt… distance. An empty chair at a table I hadn’t sat at in years. Wishing for a different mother had been a ghost I carried. I put it down gently and walked on.

Mark would be away for a long time. On the rare days when his face appeared in my mind with the vengeful sharpness of old photographs, I reminded myself that walls and time stood between us, that reality had recorded itself, that I could say his name without it rearranging my breath. I hoped he learned anything that made the world safer. I did not make it my job to supervise his soul.

On a spring evening three years after the verdict, the shelter hosted a community event in the gym of a middle school. Folding chairs, church-basement coffee, a hand-lettered banner that read You Are Not Alone. I told the story again, this time with more space around it. I talked about journals and courtrooms, about therapy and laughter returning in small, trustworthy portions. I ended with the sentence that had moved into my chest like a tenant who paid rent on time: “Silence almost destroyed me. Speaking saved me.” People stood. The applause felt like rain on dry ground. Afterward, a teenager with bitten nails and a backpack too heavy for her shoulders came up and whispered, “Me, too.” I gave her the card for the shelter and said, “There are people who will believe you.” She nodded like she believed me. I sat in my car afterward and cried because hope, it turns out, is as overwhelming as grief.

School turned into work that turned into a vocation. I became an advocate in a hospital ER, the person paged when someone arrived with injuries they didn’t know how to name. I learned to introduce myself without demanding a story. “I’m Emily. I’m here to sit with you and help with the parts that feel impossible.” I learned the shape of a morning after shock. I learned the bureaucratic map of protection orders and safe houses. I learned which police officers had the tone that doesn’t bruise and which doctors needed a quick reminder to ask What happened to you? instead of What’s wrong with you?

I slept in a bed that forgave me for needing it. I cooked meals and didn’t flinch when the knife hit the cutting board. I laughed in my kitchen and didn’t look toward a door. I dated, badly at first, then better. On my first date with someone kind, I told them my story on a third cup of coffee, not as a test, but as a fact. They cried and didn’t try to fix me. We walked by the river and named ducks. I learned what tenderness felt like when it didn’t come with an invoice.

A year later, the community center asked me to teach a series called Writing Your Way Back. In the second session, I told the group, “We were told our voices were weapons. We learned to keep them sheathed. Here, your voice gets to be a tool.” A woman in the back nodded so hard her hair fell out of its clip. Pens scratched. A man with calloused hands wrote, I am allowed to be loud. We clapped for each other at the end, one by one. No grades. Only witness.

On the tenth anniversary of my father’s death, I went to the park he took me to as a child, the one with the swings that squeaked even when you pushed them slowly. I brought a muffin I knew he would have laughed at—blueberries the size of a bad decision. I sat on a bench and said his name aloud. “David.” I told him about the shelter and the hospital, about the tape recorder in the cereal box, about the judge who said family bonds shouldn’t be weapons. I told him I was okay in the way that word means I am not where I was. I told him I was learning to love the part of me that kept notebooks as if they could save a life because they did.

Sometimes I think of the girl on the floor, cheek pressed to the boards, the belt sound still hanging in the air, and I want to go back and lay a hand on her shoulder. “You’re going to leave this house,” I would tell her. “You’re going to walk into a building with your head up and tell the truth and people are going to believe you. You are going to sleep. You are going to laugh. You are going to hold a microphone and someone will say Me, too and you will know you have built a bridge with your voice.” I cannot go back, but I can write it here where she can find it when she needs it.

I keep that acceptance letter from long ago in a folder with court documents and certificates. The paper has softened at the folds where I hid it under a notebook. It feels like a relic from a religion I still practice: the belief that you can move toward a life you cannot yet prove exists. I also keep one more thing in that folder—a small, square photo printed from a phone. It shows me at a podium in a community gym, a banner behind me that reads You Are Not Alone. My mouth is open. My eyes are steady. The caption reads: Emily Carter, Speaker. Survivor. Advocate.

On a quiet night not long ago, I stood by my apartment window with a mug of tea and watched the city light itself. Somewhere, sirens wailed and stopped. Somewhere, a baby cried and settled. Somewhere, a door closed gently on purpose. The silence in my room felt like what I had been promised as a child and not received: safety. I wrote one last sentence in my journal and underlined it: My life is mine.

I turned off the lamp. The room grew soft. The quiet wrapped around me, not like a command, but like a blanket. This time, it was a sanctuary, not a sentence.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS. CH2

Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS Part 1…

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call. CH2

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call….

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant. CH2

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant, i…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I Was… CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I…

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… CH2

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… …

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner. CH2

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner …

End of content

No more pages to load