On Thanksgiving, My Sister Found Out I Had $18 Million—And My Family Wanted… They Had To Regret It

Part One

I never used to notice the smell of rubbing alcohol. After Sierra was born, it lived in the house with us—on the banister, the door handles, the plastic bins labeled with Sharpie and stacked like a war bunker in the hall. It seeped into my hair, into the seams of my clothes, into every sentence my mother ever said beginning with, “Not now, Elena,” and ending with a closed door.

I didn’t hate my sister. I hated the way the world reoriented for her, as if the sun had always been meant to shine through her window. I hated how a sneeze from me sent me to Grandma’s and a fever from her summoned an army. I hated that I learned how to fold myself smaller to fit inside a house that had decided I was contamination.

There was one person who didn’t treat me like I was a risk to be managed. Grandma Mavis’s living room smelled like cinnamon and old books, and if you stood in the doorway at dusk, the glass cabinets glowed as if the jewelry inside remembered being worn to dances where the air was sweeter. She let me touch the pieces with clean hands and a steady breath, and she taught me the difference between real pearls and their pretend cousins, between gold that kept promises and gold that flaked when you scratched it with a toothpick.

“This,” she said one rainy afternoon, holding up a hairpin that looked like moonlight caught in metal, “is a Victorian mourning piece. See the clasp? No machine. Hands made this. Hands that knew what they were doing.”

My own hands were small and careful, and for once, that mattered. School made sense, too—the numbers did what they were told, the essays turned into letters of admission when you fed them enough midnight. But when I brought home good grades, I got a nod and a list of chores. When Sierra made a sound vaguely resembling “Hot Cross Buns” on a plastic flute, the living room turned into Carnegie Hall.

When I was twelve, I watched the auditorium fill with other kids’ families and performed a Chopin prelude to thunder that belonged to strangers. Two weeks later, Sierra breathed into a flute for eight minutes and both sets of grandparents cried. That was the day I stopped knocking on closed doors.

I learned to be useful. I learned to disappear. I saved the parts of me that needed oxygen for later.

Later came with a full scholarship to Berkeley, and the only person who hugged me in the parking lot was Aunt Lorraine, pressing a silk-wrapped envelope into my palm and whispering, “Your grandmother left this for you.” Five hundred dollars and a promise: I wouldn’t come back empty-handed. My parents didn’t take a picture. Sierra took my room.

Berkeley felt like someone had opened a valve. I lived in the library and the museum and a coffee shop that tolerated the way I took my exams apart like engines. I majored in art history with a focus on jewelry and metallurgy, because people smirk at the uselessness of beauty until it pays more than their useful lives ever will. I worked at a diner at five a.m., at a museum at noon, and cleaning offices at two a.m., and I slept when I could—four hours here, twenty minutes there, long enough to dream I was in Grandma’s living room again.

The first job out of school—assistant appraiser at a San Francisco auction house—smelled like mothballs and old perfume. The men in jackets called me “kid” and sent me to catalog boxes that had been mislabeled three owners ago and misjudged every time since. In a plastic bin behind a torn sash and a handful of rhinestones, I found a brooch so ugly it made me suspicious. The engraving was too patient, the weight wrong for costume, the clasp a whisper of someone who didn’t speak machine.

I spent two days between microscopes and archives, cross-referencing European hallmarks and emailing a retired Parisian jeweler who still read the lonely forum where the obsessed talk to each other. When I handed my research to the director, he asked me if I knew what it would mean if I was wrong. I did. The brooch sold for $61,200 to a woman whose grandmother had probably worn its twin to funerals for people whose names no one remembered anymore, and they gave me five minutes at the Christmas party to thank me for spending my twenties on the truth.

It’s funny how your life line straightens on the graph and still no one back home notices the axis moved. “Still at that little antique place?” my mother would ask as she dabbed Sierra’s forehead and I held the vacuum. “Still there,” I’d say. “You should get a job in tech,” Sierra added, chewing with an open mouth. I smiled. That morning, I’d signed a $200,000 authentication contract with a collector who wore suits that cost more than my car.

I noticed something else: I was making other people very rich. The house got the press release and the lion’s share and I got a salary and thank yous that sounded like lines from a play. Late one night, I looked at my spreadsheet, at the percentage I would have kept if the name on the check matched the name on my birth certificate. Then I signed a lease on a room above a French bakery that smelled like butter and old wiring, and I carried a folding table up the stairs by myself and wrote on the door in vinyl letters that peeled at the corners: Elena Hart Appraisal & Authentication.

I didn’t have investors; I had reputation. That is more powerful than people who expect you to be grateful for exposure think. The antique dealers started sending me the pieces that made them itch—the ones that insisted they were more than their first glance. Then a collector called with a chest of family jewels and a fear that he would sell a memory and keep the lie. Two of the pieces turned out to be from a lost series by a Parisian master who died in a war that swallowed his name. The auction raised $918,000. My commission was 10%. I sat under the bakery smell and let the tears come because there are only two times you should cry in business: when you fail to keep a promise and when you realize you just kept your promise to a little girl in a cinnamon-scented room.

The office grew up before I did—new walls, a front desk with velvet, a young gemologist whose hands were as careful as mine had been. Los Angeles. Seattle. A tiny sign in New York. My calendar filled a season ahead; some clients waited three months for a yes because the truth takes time and refuses to be rushed. The numbers in my accounts stopped being maybes. I looked at them the way you look at a landscape after a storm—carefully, grateful, aware of every broken branch.

Home did not change. “Still at that little jewelry place?” my mother asked over chicken that had been asked to be chicken a second time. “Still there,” I said, and counted down the minutes until my flight. Sierra rolled her eyes and filmed herself for people whose attention she mistook for affection.

Then she stumbled into my room on Thanksgiving and saw my bank balance.

Here is the thing about secrets: the ones you keep to protect yourself never feel like secrets, just boundaries. The ones that get dragged into a living room by a sister who has never done an honest inventory in her life turn into weapons.

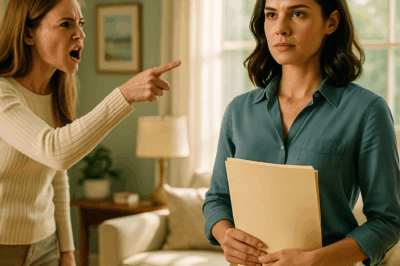

“Eighteen million,” she said, holding my laptop like it was Exhibit A at a trial we had both turned up to without counsel. “You’ve been hiding it while we’ve been struggling.”

The funny thing is, entitlement dresses itself in the vocabulary of virtue. My father pressed his lips together like a man about to deliver a sermon. “We raised you,” he said. “You owe this family.”

Sierra wasn’t shy. “I’m not asking for much,” she cooed. “Two million. A condo. A fresh start.” My mother didn’t bother with a prelude. “Your father and I found a place in Naples. Only three million.”

I looked at them all—faces I had begged to notice me, eyes that had learned to slide off me like I was shelf paper. Not one of them had asked how I had done it. Not one had said congratulations, or I’m proud of you, or tell me everything.

“Funny,” I said, my voice so calm I could have floated on it. “I’ve been sending seven thousand a month to your account for two years. Quietly. So you wouldn’t lose the house.”

My mother’s phone pinged. My father’s face broke open then snapped shut. Sierra said I was lying because lying is easier than looking at the ledger. I slid my laptop into my bag and my chair back under the table. You know the rest: I told them no. They called me ungrateful. I smiled at the door on the way out.

The internet did what the internet does. Sierra posted a picture of us at six in matching dresses and wrote a caption that would have worked if memory didn’t exist. The comments came in with claws. I read them with the detachment that comes from eating instant noodles alone at a table you bought with the tips your feet earned and thinking, Someday, I will be able to afford rage. That day had come and gone; all I had left was patience and a good lawyer.

They showed up at my office anyway—my father with that face men in suits wear when they believe rooms belong to them, my mother with her church expression, my sister with her phone framed at an angle that made her tears catch the light. Security escorted them out with the kind of professionalism that used to belong to other people’s lives. I cancelled every wire transfer in public—my mother’s phone buzzed in her hand like an accusation—and added all three names to a do-not-enter list because boundaries are not roses; they don’t look pretty and smell sweet. They are fences with teeth.

That night, my phone rang and the caller ID said MAVIS and I sat down on the floor like a child at story time. “Well done,” she said, and I put my face in my hands because there are only two times you should cry in business, and sometimes the second one arrives as a blessing with your grandmother’s voice. “You stopped begging to be seen,” she added. “Took you long enough.”

The thing about clean endings is that they only exist in books. The real ending looks like this: Sierra threw a tantrum on Facebook and then opened a jewelry authentication company with a logo that looked as if it had been designed by someone who thought Tiffany & Co. was the same as the font on a prom invitation. She mislabeled a Cartier bracelet as fake and went “viral” in the way people do when strangers enjoy watching them fail. My staff sent me screenshots. I didn’t comment. The company folded in six months because a business is not a mood board; it is work.

My firm grew. I opened in Palm Beach and hired a woman whose hands were steady and whose instincts were excellent, and we authenticated a duchess’s locket that turned out to have been re-set with a paste stone in 1932 by a man who cheated but did good work. We told the truth; the family paid for the truth; we slept at night.

You want to know what I did with the money? I paid my people well. I bought a place with a door that only opened for me. I started a small program in Mavis’s name that paid for girls who loved old things to go to school without apologizing for their joy. I rented a storage room at the museum where I got my first job and filled it with tools my younger self would have broken the rules to borrow. I slept, sometimes. I said yes to clients who respected my time and no to anyone who tried to pay me in access. I learned to tell the difference between old money and money that just thinks it is.

On Thanksgiving, I bought dinner for a dozen people who had become my family while my actual family was still arguing about whether I owed them anything besides a good reason to examine their own mirrors. The table was full of laughter that didn’t have a price tag, and when the bakery under my first office sent up a tray of croissants that tasted like butter and mornings, I said a quiet thank you to a girl who used to count change for coffee and think, One day, I will be able to buy the whole pot.

I haven’t seen my mother in two years. She wrote a letter that tried to rewrite the past and forgot to use the words I’m sorry. I saved it in a folder labeled NICE THINGS WE DON’T OWN. My father ran into a friend of a friend at a charity gala and asked if I ever asked about him. I didn’t. Sierra sent me a link to a GoFundMe and wrote “family is family” and I turned off my phone and refilled my glass and did not feel guilty.

They wanted my money on Thanksgiving. They thought it would taste like victory on their tongues. They wanted to turn my bank balance into a story about obligation so they wouldn’t have to write their own stories about effort.

I did the quietest, loudest thing you can do to people who have made a meal of you for years.

I left them hungry.

Part Two

Freedom doesn’t come with a marching band. It comes with keycards and good locks and a calendar no one else writes in red ink. It comes with the first morning you wake up and don’t check your phone for a demand disguised as a plea. It comes with work that belongs to you, bruises you chose, and joy that no longer needs to be defended in court.

The messages slowed and then stopped not because they ran out of accusations but because they found a new audience. I still saw the posts—friends of friends have screen-grabbers and senses of humor—but they became noise at the edge of a soundtrack to a life that had learned to play itself in a new key.

Then the thing I had not prepared for happened: the story traveled. Not the Facebook melodrama; that burned out in a week, the way all cheap fires do. Quiet people, the kind who keep rooms running and contracts honest, told other quiet people: there’s a woman who does the work right and doesn’t let herself be eaten.

A widow in Palm Beach called to ask if I would tell her whether the ring her husband had said was a blue diamond was actually a blue diamond. It wasn’t, and she cried in relief and bought herself a trip to Paris with the money she didn’t lose. A diplomat’s son in Rome sent me a bracelet his grandmother had called “my treasure”; it turned out to be valuable only because she had called it that for sixty years. I valued it accordingly and didn’t charge him for the extra hour it took to explain why a clasp that stuck tells a different story than a clasp that doesn’t.

We landed the imperial job—the one estate people whisper about over drinks and then pretend they didn’t. Thirty million in velvet and history. I flew to a country I’ll never name and wore white gloves for twelve hours and ate almonds out of a paper cup because the work didn’t stop and it felt right to be hungry in the presence of so much wealth that had survived so many hands. When I signed the report, my wrist ached and my grandmother felt very close.

When business slowed, because even triumph has seasons, I learned how to sit still. I went to the tiny museum where I used to catalog donations and found my old boss, older now, dust in the lines around his eyes. We drank bad coffee and he asked me, “How did you do it?” and I told him the truth: I didn’t wait to be allowed.

I moved. The penthouse was a beautiful idea, but it felt like an uninterrupted thought—too clean, too high. I bought a townhouse with uneven floors and a courtyard that catches the kind of sunlight that makes the simplest breakfast taste like a child’s hand on your cheek. The security is good. The neighbors keep their own business. The air doesn’t smell like someone else’s ambition.

I kept my promises to the girl upstairs with the laptop. I cook on Thanksgiving every other year—for friends who arrived by accident and stayed on purpose—and on the years I don’t, I write checks that make other people’s dining tables bigger. I told my therapist, “I think I’m happy,” and when she asked me what that looks like, I said, “It looks like not thinking about my mother when I buy a winter coat.” She smiled like I had handed her a rare stone.

Sierra tried again to turn my life into her content. She posted a video of herself in a dim living room talking about “healing from a sister’s betrayal,” her voice catching on the words as if tears had rental agreements. The comments were kinder this time; perhaps people get tired of looking at the same wound and not seeing any scar. I didn’t look at it twice. I was reading grant applications from girls who can tell the difference between Art Deco and Art Nouveau with their eyes shut and want to write research papers about clasp patents instead of apologizing for not wanting to be dentists.

I don’t hate my family. That would mean I’m still tied to them. What I have is lighter than hate and heavier than indifference. It’s a decision. I can love the child I was in that house and refuse to invite the adults it made to dinner.

When the call came, I was in the airport in Hong Kong, eating soup too hot for airplane lips. Aunt Lorraine’s voice sounded like a porch light in fog. “Mavis had a small stroke,” she said. “She’s stubborn. She’ll be fine. But she asked for you.”

I flew home and went straight from baggage claim to the hospital that smelled like the thing my childhood had been preserved in. Grandma’s hair was thinner, her hand still her own. She squeezed my fingers and said, “Tell me something good.”

“I bought you a ring,” I said. “With a stone that knows how to keep its color.”

She laughed and then coughed and then laughed again. “You always knew what would last.”

“She taught me,” I said.

“No,” she said, stern even now. “I showed you the door. You walked through.” She dozed. I watched the lines in her face and thought about the women in my family who had never been allowed to want more than a house that did not slip under their feet. I thought about my mother and wondered how much of her cruelty was exhaustion and how much was choice. It didn’t matter, I decided, not because it wasn’t interesting but because my life didn’t hang on that answer anymore.

The nurse turned on a lamp with a shade like a halo and said it was time for me to let her sleep. In the parking lot, my phone buzzed. UNKNOWN: Your grandmother asked for me and not for you? The number was my mother’s new one. I blocked it. Some doors are not meant to be held open.

On the first Thanksgiving after the lobby incident, my phone stayed quiet. That felt like a miracle and a holiday and a good night’s sleep. I roasted a turkey that tasted like I had been paying attention in kitchens all my life and I made stuffing that would have made Martha admit that competence is one flavor of love. A friend brought her baby and handed him to me without instructions. He drooled on my shoulder and grabbed my hair and I didn’t think at all about Sierra taking my room or about being sent to Grandma’s when the thermometer said ninety-nine. I thought about how soft baby hair is and how grateful I was for a life that had taught me to hold gently.

The next year, I took Thanksgiving off. Some people find their peace in feeding; mine sometimes needed a passport. I sat in a courtyard in Rome with a plate of artichokes and watched a man tune a violin. The aqueducts don’t care about your family stories. They carry water. They hold. I cried a little, but not the kind of crying that empties you out. The kind that makes room.

When I flew home, I found a letter in my mailbox in a slanted hand I knew from library slips and flour recipes. “Your grandmother asked me to give you this if she went first,” Aunt Lorraine had written on the sticky note stuck to the envelope’s corner. Inside: a clipping from a magazine about a woman who had authenticated a duchess’s locket and a check for fifty dollars made out to ELENA HART dated five years ago. In the memo line: “For your first business card.” Enclosed was a smaller note, Grandma’s voice unmistakable even on paper: “I always knew you loved the kind of truth you can hold.”

I framed it and hung it in the hallway by the door where I grab my keys. I touch it when I leave. It feels like armor that doesn’t make me heavier.

You asked for an ending. This is as close as life gets: my office smells like glue and velvet and the coffee my assistant insists is better than mine; my calendar has white space and words like VACATION written in block capitals; my phone lights up with clients who respect a no and friends who bring soup without warning; I sleep in a house where no one has ever been punished for sneezing. My bank balance is a number I still can’t say out loud without the little girl in me looking around for a grown-up to make sure it’s true.

On Thanksgiving, my sister found out I had eighteen million dollars and my family wanted a piece of me they hadn’t been willing to help build. They had to regret it, because I did the one thing they never thought I would: I let them.

I don’t check Sierra’s posts anymore. I don’t read the comments under photographs of houses in Naples with captions about dreams deferred. I don’t answer numbers I don’t recognize. I don’t sit at tables where the cost of a plate is measured in self-erasure.

Instead, I take the long way home through a city that has forgiven me for leaving and taught me how to stay. I press my thumb to a fingerprint scanner and step into a life that smells like butter and old wiring, velvet and truth. I pour a glass of wine I don’t need in order to sleep and hold it up to the light like a gem and think, this is what it looks like when a woman is her own inheritance.

And then I sit down at my table, open a folder, and do the work that has always loved me back.

END!

News

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… CH2

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… Part One I…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited me Over Just to Tell me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited Me Over Just to Tell Me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her …

At My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. CH2

My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. Part One…

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And then.. CH2

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And…

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a… CH2

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a … Part…

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration. CH2

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load