Nobody from my family came to my graduation, not even my husband or kids. They all went to my brother’s barbecue instead.

Part One

Nobody from my family came to my graduation, not even my husband or kids. They all went to my brother’s barbecue instead.

I thought I’d prepared myself for any outcome—maybe a late arrival, maybe a rushed hug between the ceremony and dinner. I hadn’t prepared for five empty seats with little white name cards under the auditorium lights: Reserved: Nathan Williams. Reserved: Ethan Williams. Reserved: Sophia Williams. Reserved: Robert and Diane Hart. Reserved: Melissa Hart.

I stood at the edge of the aisle with the other graduates, cap bobby-pinned into the bun an exhausted stylist had coaxed out of my fine hair that morning, gown rustling at my knees, throat tight enough to crack glass. A row of strangers stood behind me, good-naturedly jostling, smiling into phones held high. In front of me, a boy no older than twenty-two whispered, “Congrats, Mom,” into his mother’s neck as she cried and laughed and tried to fix his hood at the same time.

I swallowed. If I looked up to the upper balcony, I could pretend that my family was late, that they were elbowing through the rows, whispering apologies, that my son would whistle that obnoxious whistle he learned at age nine and my daughter would wave both arms like flags. If I looked up there, I might survive the walk across the stage. So I looked up.

Nothing.

“Alicia Marie Williams, Master of Business Administration, with honors.”

I moved. I shook hands. I took the ceremonial diploma case. A camera flash went off somewhere above the stage. I turned and the dean smiled like every dean in America smiles at every ceremony in every arena. He didn’t know that the sound I made when I exhaled was the sound of something small and bright going out.

After the recessional, I found a patch of grass behind the engineering building, out of sight of the photo mobs and the family herds. I pressed my forehead to the cool bark of a birch tree and breathed until the edges of my vision stopped going gray. When I pulled my phone out, there was a single text from Nathan sent twenty minutes earlier.

Nathan: We need to talk urgently.

Under it, my notification feed scrolled into the absurd: 45 missed calls from “Jenna — Derek’s wife.”

Jenna. My brother’s wife. The one who curated backyard parties like a profession and did seasonal color stories for her charcuterie boards. The one who’d invited my children two weeks ago—“Of course Ethan and Sophia should come, Ali! We’ll set up the big slide!”—as if my graduation were a PTA meeting that could be rescheduled for better weather.

I dialed Nathan. He picked up on the first ring.

“Alicia,” he said without hello. His voice was pitched high, loose with panic. “Where are you?”

“Campus. What happened?”

“Ethan fell.” I could hear ER sounds behind him: a monitor’s beep, the low wheel squeak of a gurney, a child wailing at a distance. “He was climbing the new slide Derek installed—Jenna kept telling him no running, but you know Ethan—he slipped. The doctor thinks it’s a broken arm. We’re at Memorial.”

I already had my keys in my hand. “I’m on my way.”

“And Alicia—” The sound of his breath catching made me clamp my teeth. “He keeps asking for you.”

I jogged to the far lot in my too-high heels. By the time I reached the car I was barefoot, condolences from the pavement printing on my soles. The navy dress I had carefully chosen clung damply to my back. My cap and gown slid off the passenger seat and onto the floor as I peeled out of my spot.

I drove with surgical focus, my grief and my fury shoved into the trunk with the wrinkled graduation robe. The city blurred around me. At a red light my phone vibrated on the console: Jenna again. Then Derek. Then Mom. I ignored them all. The only voice I wanted was a fourteen-year-old’s muttered “Hi, Mom,” stubbornly casual because fourteen is an age that demands cool even in an ER.

Memorial’s parking lot was stuffed with SUVs and a parade of “Visitor” badges. I sprinted, hairpins loosening, mascara smudging. The ER receptionist was brisk and kind. “Bay Seven,” she said. “Right this way.”

The curtain rings scraped. Ethan lay on the bed, his right forearm in a temporary splint, his cheeks blotchy from crying and scraped along the temple where he must have hit the slide. Sophia stood at the foot of the bed with a packet of peanut butter crackers she hadn’t opened, chin up, eyes hard, being brave like eleven-year-olds are brave when it’s for someone else. Nathan’s hand hovered near Ethan’s shoulder without touching, as if he were afraid his palm would shatter the boy.

“Mom,” Ethan said. He said it like a fact and a relief. It wasn’t a toddler’s cry or a teenager’s growl. It landed in my chest and loosened something.

“I’m here,” I said, and in that moment everything else dropped away. I sat and smoothed his hair back from his forehead. “How bad, baby?”

“Just a simple fracture of the radius,” a doctor said, stepping in as if he’d been waiting for his cue. His tone was warm, efficient. “Painful, yes, but straightforward. We’ll do a proper cast and he’s going to be fine.”

“Can he still play soccer?” Ethan asked, instant panic.

“Maybe not for a few weeks,” the doctor said with a conspiratorial wink. “But you can sign your cast like a rock star.”

The doctor left, and with him went the decent excuse for silence. My mother put a hand on Ethan’s leg, careful of the splint. My father smoothed his beard and asked the doctor another question he’d already asked. Derek, usually eager to narrate any story, stared at the floor tiles. Nathan looked at me with one expression in his eyes and another on his mouth.

I chose the one I could live with.

“We’ll take him home,” I said. “Nathan will pick up the prescription on the way. I’ll set up the couch and bring down extra pillows.”

“We can follow you, dear,” my mother offered. “I’ll make chicken soup.”

“No,” I said, and the word felt like an anchor casting. “Thank you, but no. We need quiet.”

The ER nurse arrived with casting supplies and a practiced smile, a rescue signal. “We’ll take him to radiology for a minute, then we’ll get this arm pretty in blue,” she chirped, and the two of us went with Ethan, me holding Soph’s hand in the hallway while a transport tech who looked like he should still be in high school pushed the gurney.

“Mom?” Ethan said quietly as the tech flipped a lever and the bed rose an inch with a gentle hiss. “Sorry I missed it.”

“It’s okay,” I lied. “You’ll see the photos. We’ll have dinner this weekend to celebrate.”

“Not spaghetti,” he groaned, as if to prove he was still him. “Spaghetti is pain with one arm.”

“Deal,” I said, throat thick.

Back in Bay Seven, my parents and Derek had migrated to the cafeteria. Nathan stood with the discharge forms. “I can go in the morning and make copies for school.”

“We’ll talk later,” I said. “About all of it.”

On the way home, Ethan dozed off to the rhythm of turn signals and the muffled radio. Nathan drove very carefully, as if observance of every posted sign could retroactively absolve him of the reckless choice he’d made that morning. Sophia kept glancing at me like she wanted to ask a question she wasn’t sure she had the right to ask.

At home, we made a nest on the couch. I slid a pillow under Ethan’s wrist with the tenderness of handling a sparrow. Sophia fetched a worn blanket that still smelled like younger years. I texted my friend Linda in a daze—she had sent me a message from the graduation lawn that I had ignored. Dinner? I typed. Anything that isn’t spaghetti?

Linda arrived an hour later with rotisserie chicken and roasted potatoes and a salad that made me think of summer. She took one look at my face and wrapped her arms around me while I went rigid and then melted. “Congratulations,” she whispered into my hair. “I know you’re not going to let them take this away from you.”

Nathan hovered in the kitchen, inventorying silverware like it was suddenly complicated. When the kids ate, Linda and I stood at the sink and washed plates as if they were absolutions.

“You look like the day after quarter-end,” she said dryly.

“I feel like I’ve closed a five-year file and someone set fire to the archive.”

“You were never going to get a clean ending with them,” she said. “But you did get the degree. They can’t take that.”

When Linda left, the house sank into quiet. Ethan drifted first, cast propped like a small blue monument. Sophia climbed into my lap as if she hadn’t done that in three years, settled her head against my collarbone, and started to cry. “I wanted to go,” she whispered. “But then Jenna said—then Dad said—and I thought if I complained you’d get mad and you’ve been studying so much already and—”

I pressed my cheek to the top of her head. “I’m not mad at you,” I said. “I’m disappointed in choices adults made. I’m proud of you for telling me the truth.”

Nathan stood in the doorway, hands stuffed in his pockets like a boy who’s gotten a D. “Alicia,” he said, voice low so it wouldn’t carry down the hall. “Please.”

“We’ll talk in the morning,” I said. “After I sleep as much as a human can sleep in a night.”

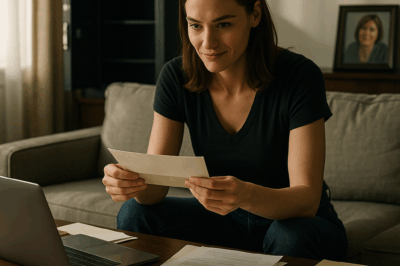

We didn’t. Not really. I lay awake with the kind of bone-drone exhaustion that keeps your body buzzing while your brain replays the day in new and exciting angles that each hurt a different way. At 3:10, I gave up pretending and pulled out my laptop and wrote a list called AFTER and another called DURING. In DURING: schedule PCP appointment for Ethan; email HR about new title; pick up dry cleaning; cancel the reservation at Bellissimo that had never been used. In AFTER: think about therapy; think about marriage; think about what mattered at 35 that hadn’t at 25.

At 7:02, my phone pinged. A new message from Jenna lit the screen: a photo of the kids from the barbecue with a caption in bubbly font: Can’t wait to celebrate our grad right, familia! The timestamp was from an hour before the ceremony. My stomach flipped. I closed the messages and opened my camera roll and looked at a picture I had taken alone in the mirror, cap square, tassel straight, eyes trying so hard to shine they looked peeled.

It wasn’t that I wanted them to grovel or send florist trucks or build a shrine out of balloons and Costco sheet cake. I wanted what my children had when they stepped on a soccer field, what my brother had when he talked clients through a contract, what my father had when he secured a bid: eyes on them, clapping at the right time, a body in a bleacher saying yes, you, right now, well done.

It was too late for that. But it wasn’t too late for this: to stop letting other people choose which page I got to live on.

When my phone buzzed at 8:14 with the same urgent message from Nathan, I slept through it. When it buzzed with the first of the forty-five calls from Jenna, I swiped away, then put the phone on silent. I can’t say if things would have changed with that one decision. I can say I reached the hospital as quickly as I could once I knew, and I can say that after the cast was blue and Ethan’s breath was even, I picked up my purse and my keys and I said to Nathan, “I’m going to need a week.”

“A week where?” he said, not angry. Scared.

“At the Marriott,” I said. “The one I booked for my parents. It’s prepaid.”

“You’re leaving?” His eyes flicked toward the hallway. “Now? With Ethan—”

“I’ll be here every afternoon,” I said. “I’ll check on homework. I’ll drive the carpool. I’ll bring soups. But I am going to sleep in a room where no one tells me a barbecue is more important than the work I’ve done for five years.”

He lifted his hands a fraction of an inch. “Okay,” he said, voice thick. “I deserve that.”

“I know you do,” I said, and kissed my son’s hair.

Later, when the hotel door closed behind me and the HVAC hummed its bland lullaby, I took off the cap that had lived in my trunk and put it on the bed. I slid my diploma—still in its ceremonial case—out of my bag and leaned it against the TV. Then I turned off the lamp and went to sleep at 8:43 p.m. and didn’t wake up until sunlight had climbed all the way up the curtains.

Part Two

The first morning of my self-imposed exile dawned clear and cold, Seattle doing its clean-sky-after-rain imitation of a city that forgives. I showered in water so hot my ears pinked and drank coffee from a paper cup with my feet tucked under me on the armchair by the window. The city below went on without me—the I-5 like a gray river, the pedestrians in puffy coats, the fruit stand man building pyramids of oranges like he meant it.

My phone had stacked: twenty-seven texts from Nathan of steadily escalating apology; twelve from my mother that were mostly adverbs—truly, deeply, sincerely; a long one from Jenna that started with OMG and ended with a broken heart emoji; three from Derek that read like copywriters did contrition: I miscalculated tone. I center-stage too often. I love you. I responded to none of them. I wasn’t punishing them; I was protecting me.

At 10:00, the Marriott breakfast ended. At 10:01, my door knocked.

“Room service,” a voice said that was not room service.

“Who is it?”

“Linda, bringer of bagels and gossip. I come bearing smoked salmon and chewy carbohydrates.”

She came in with a paper bag that smelled like comfort and salt. We ate with our feet touching and our hands wrapping around mugs.

“I had a fantasy yesterday,” she said around a sesame seed. “I was going to throw your cap at Nathan. Not at him, exactly. Past him. So he had to watch it arc.”

“Thank you for not getting arrested,” I said.

She took my hand and squeezed until our knuckles made matching little white ovals. “You get to be angry,” she said. “And you get to be proud. Both can fit in the same ribcage.”

In the afternoon, I went home and helped Ethan figure out how to tie his shoes one-handed. He tolerated it with saintly patience that he will never display for anything else as long as he lives. Sophia sat criss-cross on the floor and narrated the process, which made it worse because she is Sophia.

At dinner, Nathan put his fork down between bites with the deliberation of a man practicing difficult news in his head.

“I emailed HR,” he said. “I told them I need to shift my work hours for a month so I can handle Ethan’s appointments and after-school. I asked for two work-from-home days.”

“Good,” I said. I didn’t say I had done that every month of flu season for six years and called it “lucky” when my boss allowed it.

“And I texted Derek,” he added.

I looked up. “And?”

“I told him not to put our kids in the middle of his party planning ever again. I told him that what he called ‘low-key’ was actually sabotage.”

“Wow,” Sophia said. “That’s a speech.”

“He has more,” Ethan deadpanned. “Trust me.”

When the kids were upstairs brushing teeth, when the bathroom fan had started its rattling chorus, when the evening softened enough to make honesty possible, Nathan came around the table and knelt in front of my chair.

“I’ve been afraid,” he said without hedging. “Not of you. Of what your degree means. Of you changing. Of me not changing fast enough. So I didn’t show up when it mattered because if I showed up, it would mean accepting we were at a new level and I might not be able to reach it.”

“It’s not a ladder,” I said, and my voice surprised me by not breaking. “It’s a table. There are more seats now. But you have to sit in them.”

He rested his elbows on my knees and folded his hands. “I want to. I really want to.”

“I’m going to therapy,” I said. “Whether you do or not.”

“I will,” he said. “Pick the therapist. Smart ones scare me enough to listen.”

The next day I made the appointment. On the intake form, under chief complaint, I wrote: Chronic minimization. Acute graduation day. Under goals, I wrote: To stop being grateful for crumbs.

On day three of the Marriott, I called my mother. “We can have tea,” I said. “At my house. On Saturday. You, Dad, no one else.”

She arrived with a tin of cookies I knew she had taken from Derek’s pantry because the handwriting on the label was Jenna’s. She cried on my couch and I let her because crying is sometimes atonement and sometimes theater and sometimes simply the body making salt. My father stood in the doorway and looked at our family photos as if they were oil paintings he had to appraise.

“We wanted to do this later,” my mother said. “A big party. A speech. Balloons. I didn’t realize how much you needed it on the day.”

“I didn’t need balloons,” I said. “I needed bodies in seats.”

My father cleared his throat, a sound I have heard beginning and ending arguments my entire life. “Your brother told us—”

“I don’t care what Derek told you,” I said, and my voice came out like a well-struck bell. “I care that you believed it without checking with me while my name was being read in a room full of strangers.”

My mother pressed a napkin into her palm until it had little quarter moons in it. “We can’t fix that.”

“You can’t,” I agreed. “But you can stop asking me to be smaller in advance to prevent you from having to feel guilty afterward.”

She flinched, and then she nodded. “Okay,” she said. “We will try.”

They left after an hour, three cookies missing from the tin and one vow humming in the walls. On the way out my father touched Ethan’s cast like it was something holy and said, “We’ve been awful idiots.” It was not the apology I needed; it was the one he had, and I took it as a promissory note.

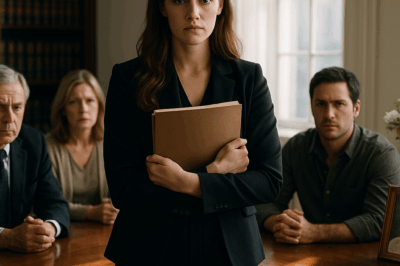

On the fourth day of the Marriott, Derek called. “I’m assembling a celebration,” he said. “For you. Dinner at that Italian place you love—what is it?—Bellissimo? Saturday two weeks from now. Just friends and colleagues. Jenna and I will host. No speeches from me. I promise.”

I thought about the fifteen times I had let his invitations excuse my parents from mine. I thought about Jenna’s forty-five missed calls pinging my ignored phone while my name floated through an auditorium without an anchor. “Invite Linda,” I said. “And my cohort. And my boss. If you do that, I’ll come.”

He did. He really did. The evening was lovely: white tablecloths, clinking glasses, a cake frosted in navy and gold with Alicia MBA in a script I wanted to learn to write. My father stood at the corner of the room with a glass he didn’t raise and watched me accept a set of bullshit Italian toasts. My mother laughed when she was supposed to and blinked hard when she thought no one was looking. Jenna wore shoes that could have killed me and touched my elbow three times and said “We’re so proud” like she had practiced.

After dessert, Derek stood up and kept his promise. He didn’t give a speech. He handed me an envelope. Inside was a gift card to the printer I liked best. “For the paper you’ll write next,” he said, lightly, but his eyes were solemn. “And for the print you’ll hang in your office.”

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it.

The office happened a week later: the promotion came through, the door to a room with my name on brushed metal, three chairs, and a plant I had not yet killed. The first thing I did was hang my diploma. The second thing I did was put a photo on the shelf: me in the navy dress and cap in the hotel room mirror on a day I chose myself, eyes swollen but set.

Therapy became a place I didn’t know I needed. Dr. Hsu had a way of leaning that made you feel like your sentences could land safely on the furniture. I told her about being the responsible one, about how the brother with the barbecue had always been brighter by family room light. I told her about my mother’s adverbs and my father’s silences and my husband’s easy compromise that cost me a day I had thought could never be taken.

“Grief,” she said, when I explained the way joy kept catching in my throat like a fishbone. “Grief for a day that never happened. Grief for a version of family you wanted to be real.”

“What do I do with it?”

“You let it sit next to the pride,” she said. “You don’t make it go outside.”

Nathan came with me twice. He cried the second time, which surprised both of us, and laughed when Dr. Hsu handed him the tissue box and he took two.

“What are you afraid she’ll think if she outgrows you?” Dr. Hsu asked.

“That I didn’t deserve her to begin with,” he said, and looked me in the eye like a man who had run out of hiding places and found the door open.

Ethan learned to sign his name with his left hand in block letters that looked like a ransom note. Sophia started asking me about school—not just her own but mine. “What did you learn today?” she’d say, padding into my office while I read case studies about brand lift and CPA. “Do we still call them case studies when they’re not murders?”

At the end of the quarter, she came home with a project on Women Who Do Hard Things. The poster had Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Serena Williams and an AI engineer from the news and me. “It was supposed to be three,” she said, sheepish. “I cheated.”

“You can cheat to include your mother,” I said. “It’s in the Geneva Convention.”

On a rainy Saturday in June, my parents invited us to their house for dinner. The same house I had grown up in, the same house that had been empty of them on the day I walked across a stage. On the mantle, among Derek’s real estate awards and school pictures faded to odd greens, there was a new frame. It held a photo of me from Linda’s camera, robe draped around my shoulders, cap on sideways because I had laughed hard at something she’d said. My mother had placed that photo dead center under the clock.

When she brought out dessert, I caught her eye and nodded at it. She blushed like a teenager caught doodling names in a notebook.

“It should have been there sooner,” she said simply. “It’s there now.”

After we ate, after we stacked plates and wiped counters dry because no one in my family knows how not to do that, my father took a bottle of red from the sideboard and poured it with the precision of a man who needed his fingers to be doing something while his mouth did something terrifying.

“A toast,” he said, and his voice did not crack. “To our daughter, who did not get what she deserved on a day when she should have had it. To our family, which is less bad than it was last month and not as good as it will be next. To learning to show up.”

We raised glasses. The wine tasted like something trying to be better.

When I tucked the kids into bed that night, Ethan asked if I would sign his cast one last time before it came off. “What should I write?” I asked, pen poised.

“Something cool,” he said. “Something other kids don’t have.”

I wrote: Hard things don’t cancel fun things. Fun things don’t cancel hard things. Love does both. — Mom

His ears went pink. “That’s long.”

“You said ‘cool,’ not ‘short,’” I said, and kissed his hair.

Later, when the dishwasher hummed and the house sighed, Nathan and I sat on the porch and listened to a soft Seattle rain that had decided not to be dramatic. He took my hand.

“We will never miss another thing you ask us to show up for,” he said. “Not because we’re afraid of you being mad. Because we’re afraid of us being useless.”

“That’s a weird way to put love,” I said, but my grip tightened. “We should put it on a pillow.”

He laughed. “We’d sell three.”

We talked about Disney World in the fall because we could talk about good things without feeling like they took something from anyone. We talked about me teaching a module at work on continuing education paths. We talked about Derek trying therapy (“he found a guy who used to be a baseball coach and it’s going surprisingly well”), and about my mother joining a book club that did not allow the words “brisk” and “simply” as substitutes for apologies.

When I went upstairs, I stopped at the dresser and opened the drawer where my gown lay folded, not like a failure but like a garment I could choose to wear again if I wanted. My diploma hung on my office wall in a frame I had not needed my brother’s gift card for because my husband had bought one without asking which register to use. There were cards lined up on the shelf, some from people I had expected, some from people who surprised me—Ethan’s coach, the barista who’d been giving me free extra shots all spring, a neighbor I’d only ever waved at from the mailbox. Every one said some variation of the thing I had wanted to hear: We see you. We’re proud.

The day I graduated will always be the day my family did not show up. That is a fact written into the calendar of my bones. It is also the day I learned that I can walk across a stage without them and still be me. It is the day I learned how to ask for space without making it a war. It is the day I learned that my children can learn from my hurt the lesson I wanted to teach them with my robe—that women can be complicated and ambitious and deserving; that one empty afternoon does not cancel five full years of work; that families can be wrong and then be better.

It is a day with a broken arm and ugly crying and hospital fluorescent lights and rotisserie chicken and lemon squares and a hotel hallway that smelled like bleach. It is a day that will never be fixed, only folded into the story so the next chapter makes sense.

Months later, when my cohort’s group chat pinged to remind us about the alumni mixer, Linda sent her usual killjoy of a message: Yes, we’re all tired. No, you can’t bail. Alicia’s speaking. I was—five minutes on continuing ed and motherhood and how to not forget to clap for yourself when your people don’t. I wrote the speech on an airplane napkin and a grocery list and finally in a Google Doc at 2:14 a.m. when the house was a gentle animal.

At the podium, I looked out and saw Nathan in the second row with Ethan and Sophia on either side. Ethan waved with the hand that had not been broken. Sophia had stolen my navy cap and put it on backward. In the back, Derek stood with Jenna’s hand hooked through his arm like a comma. My parents sat in the third row, my mother with her posture like a pianist, my father with his hands folded as if in prayer or civility—I choose to believe both.

I told the room the thing I had learned most: “When the people you love don’t show up, you are still allowed to love them, and you are still allowed to love yourself first. You are allowed to say, I needed you and I did it anyway in the same breath. You are allowed to demand better next time. And when they do better, you give them another seat.”

Afterward, we took a photo with too many elbows in it. Someone yelled “One, two, three, cheese,” and Ethan yelled “No! One, two, three, Mom!” and that is the photo I keep framed on my office shelf: not the pretty one from Bellissimo with the cake and the good hair, but the one where all our mouths are mid-laugh because my son messed up the counting.

On my way out, a woman in a green blazer I didn’t recognize touched my arm. “Thank you,” she said. “I thought I was the only one who didn’t get a crowd on the day. I went to Denny’s by myself. It felt… dumb.”

“It wasn’t,” I said. “You did something hard. There are a hundred people in this room who would clap if they’d been there.”

“Then clap now,” she said, eyes bright, not joking.

So I did. In the lobby under industrial lighting and cheap carpet, I clapped for a stranger’s day, and everyone who heard it clapped too. It was small and it was late and it was nothing and it was everything. And as we walked into the twilight that makes downtown look better than it is, I thought: there are worse legacies to leave my children than a mother who starts applause without waiting for permission.

END!

News

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside. ch2

I Trusted My Mom with $8M. Next Morning She Vanished with It—I Laughed Because of What Was Inside Part…

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… ch2

I Walked Into My Son’s Hospital Room to Say Goodbye—Then I Heard the Nurse Whisper the Words… Part One…

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… ch2

For My Son, I Accepted My Boss’s Strange Marriage Proposal — But What I Didn’t Expect Was… Part One…

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… ch2

At The Courthouse Wedding, I Left My Fiancé And Escaped With A Stranger — Because I Realized… Part One…

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back. ch2

They Lied Grandma Was Dying for One Reason—So I Took Everything Back Part One The morning sunlight poured through…

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door. ch2

At the Family Dinner, My Husband Humiliated Me—and Everyone Laughed… But Then He Froze at the Door Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load