Part 1

“You left the utensil drawer open this morning, didn’t you?” she asked, stepping out of our bedroom as the late‑morning glow filled our kitchen.

“You slept in quite a bit,” I said automatically, then paused to digest what she’d said. To my right the counters formed an L into the corner. Cabinets shut. Doors flush. Every drawer closed like a mouth.

I frowned. Earlier, when I was going to make eggs, I’d opened the utensil drawer for a spatula, then the fridge, then a cupboard. I was just about to put the pan on the stove when something blunt poked my side—the drawer. I’d forgotten to close it.

“Well, that’s a pretty realistic dream,” I told my wife. She stood in the doorway, bathed in sun, wearing only her pajamas. She wasn’t a napper, never had been in fourteen years of marriage. If she was tired during the day, she said it meant she’d made the day count. She was that person: in front of the TV but not watching a movie—following a workout routine; out of the house to grocery shop; staying late at the office. Never still.

Yet here she was now, midday on a weekend, lying down on the couch.

I’d come home from the store and found her curled, blanket over her legs, head on a pillow.

“Hun?” I set the groceries down on the counter and went into the living room. I put a hand on her shoulder.

She roused immediately, yawned. “Huh? Oh. Hey. Sorry—I must have drifted off.”

“Take your time,” I smiled. “You’ve been working hard. I barely saw you all week.”

She shook her head like she was about to brush it off, and then blurted, “The store was out of the bleach we use, eh? You’ve been going through it so fast lately.”

I froze. I looked at the counter piled with groceries. Through cloudy plastic I could see broccoli, bread, pasta, but there’s no way she could have seen there wasn’t bleach.

The rest of the weekend went by quickly. She napped on the couch, and I caught up on shows and games. I love my wife, but when she’s awake there’s always something to be done. At least sleeping, she wasn’t getting after me about the brakes on the car, vacuuming the stairs, or reminding me to make dinner reservations for next week.

“How was work today?” I asked on Monday evening. We had just sat down for supper. A lasagna I’d heated in the oven. Barely a step above a TV dinner, but she didn’t seem to mind.

“Oh, it was weirdly quiet,” she replied. “I even got a nap in during lunch.”

“Really? You napped at work?” I asked, incredulous.

“Well technically it was on my break,” she scrunched her nose, “but yeah.” She scooped another bite, then added, “You’ve made too much food again.”

“What?” I looked at my plate, nearly empty. She nodded toward the pan. The rest of the lasagna sat untouched—exactly what I hadn’t plated. I looked down again to find my plate empty. When I looked back, she was already getting up, covering her plate with a napkin. Lumpy. Scraps under it. Why—

By six, she’d moved to the couch and curled without a word.

In all the years I’d known her, she never once left a table set. She did the dishes right after eating, always said if you didn’t, you’d leave them overnight and everything would be harder in the morning.

“Just stay up a bit longer,” I suggested, patting her shoulder. She didn’t rouse, and I decided not to press.

I did the dishes myself.

It kept happening. She stopped helping around the house. The floors stayed unswept, the vacuum collected dust, the pillows started to smell. Every time she woke from her naps—less and less frequently—she said something I’d done while she’d been asleep.

“You left your work keys on your desk.”

“You shouldn’t have yelled at that intern today. He’s just a kid.”

“You made a big decision after work today. But you’re glad you did what you did.”

“You forgot to get gas. Been driving around more than usual. You really need to pay attention.”

“You were so lost in thought today. You almost forgot about him.”

“You made too much food again.”

“You’re starting to fall back into old habits you thought you left behind.”

“What’s wrong with the bleach we use? Why do you suddenly look for the old kind your mother used?”

“You forgot to call in sick to work today.”

“You won’t forget about me like the others.”

I laughed the first week. By the second I was avoiding eye contact and buying more coffee. By the third I was shutting doors softly and moving through the house like a guilty burglar who still has keys.

The naps swelled to fill our days like damp creeping up a wall. She’d drift at noon, wake at one with a comment I couldn’t understand how she could know, drift again at two. Some evenings she didn’t speak at all—just turned her head on the pillow and breathed shallowly while I hovered, hands full of dishes or bills or my phone set to a brightness that made the dark look like a bruise. The aroma of the house shifted, less scented candles and lemon cleanser, more… I don’t know. I told myself it was the heat kicking on for the season. But when I stood at the hallway mirror and breathed in, I’d catch it—a thin, metallic sweetness like a secret.

On Wednesday of week four, I came home to find her sitting upright on the couch, eyes open, looking at nothing. Not the blank of sleep—the other blank. The TV remote sat on the coffee table as if set down deliberately on the exact seam between wood and glass.

“Hey,” I tried. “Pizza tonight?”

Her head turned one click—no in‑between. “You left the utensil drawer open this morning,” she said.

I stared at the kitchen. The drawers were shut now. “Okay,” I said, because who argues with the past? “Thanks.”

We ate in silence. She moved her fork like a person practicing a movement they’d read about. I watched her chew in the reflection of the dark window. My own mouth moved like a stranger’s. After dinner I stacked plates beside the sink and stood with hot water running like rain I had elected to be in. I stared at the sink basin until the rising steam blurred the chrome faucet into a shape I didn’t have a name for. In the blur I saw the intern’s eyes when I raised my voice at him last week, the flinch he tried to hide with a half‑smile. I saw the way my hand had gripped the steering wheel too tight when the gas light came on and the way the car had glided in a guilty whisper into the station. I saw my mother’s hands turning a bottle of bleach with an old label in a different kitchen decades ago and how later she’d put it away above the washer where I wasn’t tall enough to reach.

“You were so lost in thought today,” my wife said from the couch. “You almost forgot about him.”

“About who?” I asked, and the hot water steamed into my face and fogged my eyes and now I was crying, maybe, or maybe the angle of the faucet was just wrong, and either way I turned off the tap.

She didn’t answer.

That night, her voice followed me into the bedroom. It came from the couch because her body was on the couch, but it felt like it came from just ahead of me in the dim hallway where the full‑length mirror waits to show us the bodies we think we own.

“You won’t forget about me like the others.”

“Like who,” I whispered.

She didn’t answer that either.

I lay in bed and tried to make a list of others, and the list was people a better man would call: my brother, who I don’t speak to anymore because his wedding toast felt like an indictment; my father, who turned his phone face down when I called the day Mom died because grief is a marathon and he was already at mile twenty when I woke up. The intern I yelled at. The woman who cleaned our office and had stopped saying hi to me last spring. The boy I pushed into a hedge when I was twelve because I didn’t know what to do with the feeling in my chest and his name rhymed with something that fit in a chant. Benny, who I still avoided in the grocery store after that night. Old habits I thought I’d left behind. Bleach with a label my hands knew by muscle memory.

I slept badly. I dreamed of the utensil drawer jutting like a tongue, of a spatula angled like a road sign at a turn you only have once to take, of a bright white square of paper folded in my pocket with a phone number I didn’t want to dial, and my mother’s hands bracketing my cheeks, thumbs pressing under my eyes until I saw stars. When I woke my heart beat like I’d run to the edge of something and stopped.

Two days later, she started talking about tomorrow.

“You’re going to forget to call in sick to work today,” she murmured, eyes closed, voice lilted like a song. I checked the date on my phone. Saturday. I wasn’t scheduled anyway. “You made a big decision after work today,” she said Monday before I’d left. Wednesday morning she laughed without opening her eyes and said, “You’re starting to fall back into old habits you thought you left behind.”

“Like what,” I asked the blanket. It didn’t reply. She did.

“You’ll know when you smell it,” she said.

“What smell?”

“The one you can’t name,” she breathed, and the blanket lifted minutely with her breath and settled like a fact.

I started writing down what she said. At first on my phone. Then, paranoid, on paper I could fold into my pocket and take with me and maybe burn if it started to feel like evidence. The list looked like something a detective would pin to a corkboard if the case were my life and the crime were refusing to look at it.

— utensil drawer / morning

— bleach brand / Mom’s

— intern / yelling

— gas light / station

— too much food

— old habits / smell

— keys on desk

— big decision / glad

— forget to call in sick

— you won’t forget about me

Tuesday night I woke to a noise that was not the house. There are house noises you catalog over years: the sigh of the return vent at 3 a.m., the old‑bones pop of wood settling, the upstairs neighbor two doors down whose door slams but sounds like yours did it. This wasn’t one. It was the wet radial squeak of a drawer opening slowly against wood.

I lay still and let my eyes adjust. The hallway glowed faintly with the city’s spill through the blinds. The mirror caught a slice of that, a gray shape of me if I wanted it. I got up. I walked until my feet found cool tile. Kitchen. The utensil drawer was open three inches. The spatula I’d used for eggs earlier jutted like a pointing finger.

“I didn’t open this,” I said, knowing how it sounded.

“I know,” she said from the couch. Not asleep. Not awake like awake. That in‑between where you can tell the truth because part of you has gone somewhere the lies can’t fit.

“What’s wrong with the bleach we use?” she asked softly. “Why do you suddenly look for the old kind your mother used?”

I closed the drawer. The noise it made sounded like an apology. “I don’t,” I said to the handles, to the tidy row of them lined up like teeth. “I’m not.”

“You forgot to get gas,” she murmured. “You’ve been driving around more than usual.”

“I took a long way home,” I admitted, to the handles, to the night. “I didn’t want to come straight here.”

“Because of me,” she said.

Because of her. Because of the blanket and the pillow and the smell I couldn’t name the first week, and now couldn’t un‑name. Because of the way she didn’t move when I wanted her to, and the way she did move when I didn’t. Because of the list in my pocket and the way it read like prophecy written by a secretary with my wife’s voice. Because if I came straight home, I’d be here, and here was where I’d left myself weeks ago beside a couch and he was starting to look at me like he knew something I didn’t want to.

On Friday, I woke where I didn’t remember falling asleep: in my car, in the driveway, seatbelt on. The dawn made a gray soup of the street. The glass fogged with my breath. On the passenger seat, the folded square of paper with the list had bloomed with moisture like a flower printed on cheap fabric. I opened it. New line—my handwriting, but slanted the way it gets when I write against my thigh.

— the garage

I looked up, and the garage door was cracked where I’d pulled it down and not clicked it to the ground. The dark inside looked like an attention I didn’t want.

Back in the kitchen, she lay exactly as I’d left her, blanket on the same fold, pillow sunk where her head had worn it; except there was the smallest difference, like the angle of a picture frame that has been straight for a year and suddenly cants.

“You made a big decision after work today,” she said.

“I’m going to stop this,” I said. “Whatever this is.”

“No,” she said, and for the first time in weeks her eyes opened. They were glassy and clear as a stopped lake. “You’re going to finish it.”

“What is it,” I asked, and it was the only time I had managed the question out loud. I asked it like a person asking a doctor to please tell him the name of the hole he is falling into.

“You won’t forget about me,” she said.

“You keep saying that.” It came out louder than I meant. I pressed my lips together. “Forget what, exactly?”

She blinked slowly, once. “That I started dreaming about things you’d done,” she said. “And that you liked being seen.”

I laughed. It was not a nice sound. “I don’t like this,” I said.

“Then why are you doing it?”

“Doing what?” I snapped.

She closed her eyes. “You’ll know when you smell it.”

That afternoon at work I held the old bleach in my hand in my head. My mother’s hands turned it. I remembered the night she’d given me a towel damp with it and told me to scrub the baseboard. “Don’t splash,” she’d said, eyes on the floor, not on me. “It takes color.” The towel burned my fingers where the fabric failed. The smell braided itself into my hair. I looked up and caught my face in the reflection of the microwave door, and it looked like a boy doing a chore because his mother was tired and he was trying to fix the wrong problem.

At lunch, I called the hardware store two towns over. I used the voice I use when I don’t want someone to hear who I am. They had a bottle that looked like what I remembered. The label had changed a little—fonts do that with time—but the blue band across the top and the spiral logo and the square cap were there. I drove after work, two towns over, longer way home. I bought bleach I didn’t need. On the way back I pulled into a car wash even though it was March and dusk and no one washes their car at dusk in March. The man at the register said something about bugs and I laughed and he laughed and I paid in cash. When I got back into the car I put the bottle in the trunk and shut it, and the sound it made was the closest thing to a promise I had.

At home, I took the bottle into the garage. I set it near the wall. I stood there and stared at it until my breath made clouds. I told myself I was being thorough. I told myself I was being prepared. I told myself I was making a list of things that could be used if they needed to be used, and I did not finish the sentence on purpose.

When I opened the kitchen door, she said, “You made too much food again,” and the words felt like a door closing very softly on the other side of the house.

On Sunday morning she didn’t wake up at all.

She breathed. The blanket moved. But when I spoke, there was nothing. When I touched her shoulder, her skin under the fabric was warm but distant, like she was on a train. I stood there with my hand a few inches above the blanket and tried to remember how my life had looked before all the couches and lists. I couldn’t. The house had replaced the old days with these.

By evening I had convinced myself she’d sit up at eight and say something about the way I folded the kitchen towels (badly), or that I had left my work keys on my desk (I had), or that I’d thought about calling someone and hadn’t (true). She didn’t. I lay in bed and counted the space where she should be. I slept a little and dreamed of stairs going down to a room our house didn’t have and the echoing slap of my feet on concrete and the sound of something soft dragged over something hard.

“You won’t forget about me,” a voice said that was my wife’s and wasn’t. I couldn’t tell if I was asleep when I heard it or if I had fallen into the kind of waking that is worse.

I sat up. I was in bed. My breathing sounded too loud in a quiet that had stopped being peaceful weeks ago. I looked to my left. Her spot in the bed looked sunken. I could see the shape of her body; when I reached out, my hand closed on sour air. The aroma of the house had stopped being scented candles and fresh air. It was something else. The first week I called it dread as a joke and the word stuck because my nose needed a handle. Can a smell be a feeling? It must, because that’s the only word that fits.

“You won’t forget about me.”

I swung my legs over the side of the bed and flicked the lamp on, then off—too bright, it would wake her. I blinked into the dark. The hallway mirror caught my motion, a dim slice. I walked but my arms didn’t swing. My eyelids begged to blink but the air felt too thick and the blink didn’t come.

In the living room, the lump on the couch existed in the space where light and dark make treaties. Breathing? Or the floaters in my eyes inventing motion at the edge of vision? I sat at her feet. The blanket was smooth where my hands had been smoothing it for weeks; the pillow yellowed and sour beneath the curve of her skull. The movement I thought I saw was the pillow sighing and the blanket settling. Not her. Not really.

I did not take the blanket off her head.

I don’t know how she knew my intentions. Maybe we’re most awake when we sleep. Maybe whatever had been narrating my days had finally exhausted itself and gone to stand with her on that platform between worlds and wait for a train we don’t get to see arrive.

In truth, I don’t know when she stopped reciting the past and started telling the future. I don’t know if it matters. Premonition or not, this was always going to happen when she started dreaming about things I’ve done.

I smoothed the blanket atop sunken flesh. I had buried so much within the soft dirt of my memory, smoothed over by the fog of adolescence and the polish of adulthood. This was one thing I wanted to remember—to force myself to remember—because forgetting is what makes the drawer open again, the bleach go back on the shelf, the list in your pocket look like someone else wrote it.

My phone buzzed in my pocket and I jerked like a boy caught in a lie. A text from an unknown number, no name. You forgot to get gas. I stared at the screen until the words blurred, then laughed because I had a full tank. The laugh didn’t sound like me. I turned the phone face down on the coffee table beside the remote. The room reflected in the screen looked like a place I could live in if I decided not to ask any more questions.

“I won’t forget about you,” I said to the blanket.

In the kitchen, the utensil drawer clicked open three inches and stopped.

I stood up without meaning to. My feet took me down the hall, past the mirror that did not bother to show my arms moving, past the bedroom where the lamp waited to be turned on, into the garage where the old bottle sat like an idea with a handle.

I picked it up. The cap turned with the sticky complaint of something that had been closed in another era and wasn’t sure the rules were the same now. The smell reached up—sharp and clean and chemical and precise. It braided with the house’s sour, polite menace and made a third smell that was nothing you could buy.

“You’ll know when you smell it,” she’d said.

“I know,” I said to the concrete. “I know.”

Behind me, the door to the kitchen eased itself shut on its hinges. In front of me, the floor waited. Above me, the bulb in its cage haloed dust I didn’t remember raising. The cap clicked under my thumb.

I set the bottle down. I closed my eyes and saw the utensil drawer open and the spatula pointing like a sign that doesn’t tell you where it goes, only that there is a turn and you have to decide whether to take it. I saw the intern’s face, the way his mouth worked around the apology I should have made. I saw my mother’s hands, the bleach, the towel, the baseboard with its scuffed line that only showed in certain light, and me at nine trying to scrub away a mark I hadn’t made because I wanted her to see me doing something good.

When I opened my eyes, the garage looked the same. The bottle looked the same. The air had shifted a fraction. The smell had learned my name.

On the other side of the door, the couch existed, and on it the shape of a body that used to sit up and say things only I knew, and then things only I didn’t know I knew. If the future is only a past with its labels swapped, this was the moment I would remember when someone asked me later When did you know?

I took the bottle into the kitchen and set it beside the sink. I closed the utensil drawer with two fingers and watched the gap disappear. I went back to the couch. I put my hand on the blanket and smoothed it again, an old habit I could not leave behind. I leaned down until my mouth was next to where her ear would be under the fabric and said it again, slower, as if repetition could carve the words into a different shape:

“I won’t forget about you.”

Half the room believed me. The other half was very quiet and listened for the next thing I might do.

—End of Part 1—

Part 2

The bottle sat beside the sink like a dare.

I made coffee I didn’t drink. I put bread in the toaster and forgot it until the smoke alarm cleared its throat and I waved a towel with exaggerated innocence beneath it. I walked back to the couch and stood there, waiting for movement that would mean I had imagined the last week. The blanket rose and fell in the smallest cycle a body can manage without committing to a conversation with the air.

At some point I dozed upright in the armchair—the kind of sleep a person tries to pass off as meditation if anyone walks in. When I came back to myself my neck ached and the coffee had a bitter skin and the light had shifted two hand‑widths along the wall. The bleach waited. The drawer was, miraculously, shut.

On the kitchen table my list lay open where I’d left it the night before, the crease down the middle like a river cutting a state in two. I added a line with a pen that didn’t want to start and had to be bullied with angry circles.

— you’ll know when you smell it

I circled it. I stared at the circle until it looked like a hole cut through to another page.

Her phone chimed from somewhere under the blanket. For weeks she’d used it for nothing but alarms she never dismissed; now the noise felt obscene in a room that had tried so hard to be respectful. I reached under the blanket and groped until my fingers hit glass. The lock screen was a watercolor of a coastline we’d loved, with four red badges blooming at the top corner: Work, Mom, Anita, Dr. Path.

I thumbed it open, half expecting the phone to reject me. My face stared back from the reflected light and decided to accept itself. The messages were from a world where people believed in lunch plans and the liberal application of emojis.

Work: Monday is fine for PTO. We’ll need a doctor’s note after that. Tell Pete to stop cc’ing me, lol.

Mom: Call me when you wake up, baby. I heard there were layoffs?

Anita: Girl, you ghosting me? Spa Saturday or I’m coming over and dragging you out by your hair, and yes I know you don’t have any hair on your legs because you are a goddess.

Dr. Path: —

I tapped Dr. Path like a person selecting the only door in a hallway that might be unlocked.

Dr. Path: Results posted in portal. Call if you want to go over them.

My thumb hovered above the portal link and then I set the phone face‑down without clicking. Not because I am noble, but because there is a difference between seeing a thing and knowing it, and I wasn’t ready to graduate to the second.

A car rolled to a stop outside. The brakes said familiar the way only certain cars can. I froze, the way prey does in the yard when the neighbor’s cat is pretending to be a tiger.

Keys in the lock. A pause. The door opened an inch and hung there, uncertain, like it needed permission to be a door today.

“Hello?” my mother called, too bright, like a woman opening a curtain in a house that has stopped liking windows.

I slid the phone under the pillow and stood. “Mom.”

She came in with her arms already parting from her sides for a hug and then noticed the air. She stopped. The light took a step back from her face. She set her purse on the bench and arranged her mouth into something between compassion and accusation.

“You didn’t answer your phone,” she said.

“It was on silent,” I lied with ease my younger self would have envied.

She looked at the couch without letting her eyes focus. “How is she?”

“Asleep,” I said.

“How long,” she asked, a formality, like asking how far away a storm is after you’ve already been drenched.

“A while,” I said.

She rounded the couch and stopped where the blanket ended. She didn’t touch it. She didn’t touch me. She looked at the coffee on the table like it had been left out by someone she was going to clean up after later. “I brought soup,” she said, as if I’d asked for soup and this was her answering. “And that cereal she likes. The weird one with sticks.”

“She hasn’t been eating much,” I said pointlessly.

My mother smiled in the careful way you smile at skittish animals. “Then you will.”

She moved around me like I was furniture and started to tidy a room that doesn’t become tidy. Newspapers straightened into a shorter stack. Pillows patted to an illusion of plumpness. The blanket smoothed in exactly the places I’d already smoothed it into obedience. When she passed the kitchen doorway her head turned and she said, without looking, “You found the old stuff.”

“The store had it,” I said.

“Uh‑huh,” she said. She reached for the utensil drawer and opened it to prove it wouldn’t bite her and closed it again gently. “You always did like to make things ‘nice’ when you didn’t know what else to do.”

“You taught me,” I said, and then heard the shape of that in my mouth and wished I hadn’t.

She glanced at the couch. “Do we need to…?” She gestured a hand at the sentence she didn’t want to finish.

“No,” I said. The word surprised me with how quickly it left. “She’s… fine.”

My mother’s eyes landed on my face like a bird on a branch, testing for give. “Sweetheart,” she said, and touched my cheek with a hand that used to smell like bleach and now smelled like hand cream and forgetting. “Sometimes ‘fine’ means ‘we haven’t said it out loud yet’.”

I swallowed. I didn’t know which it was. I did know which I wanted it to be.

When she left, the room seemed to inhale as if someone had opened a window a quarter inch. I sat. I stood. I washed a plate that wasn’t dirty. I dipped a cloth into the sink and wiped the counter until the cloth came away as clean as it went in. I started a load of laundry I’d started three times and remembered in the rinse cycle that I hadn’t added soap the first two.

At dusk my phone lit with a text from my boss: Everything okay? He had italicized the okay with an implied tone only a text can pull off—concern lukewarm enough to reheat later.

I didn’t answer immediately. I went into the garage, because there are rooms we assign certain thoughts to, and I wanted to think a thought I knew the kitchen would resent. The garage smelled like dust and rubber and now, undeniably, the faint high clean of bleach, even with the cap tight. I closed my eyes and counted backward from one hundred. At sixty‑one, her voice said calmly from the other side of the door, “You forgot to call in sick to work today.”

I laughed until I coughed. It wasn’t an argument. It was the punchline to a joke only we were still telling.

I went back inside. I texted my boss: She’s not feeling well. I’m taking care of her. The three dots pulsed and stopped and pulsed and then his reply came, brisk: Take the time you need. Keep us posted. A kindness that felt like checking a box.

By eight, the house was dim enough that the mirror could do its favorite thing—turn the hallway into a lake you could fall into. I looked because I always look. The face that looked back had stubble and eyes sunk as if a thumb had pressed there and not let up. The corners of my mouth looked tired of being corners.

“Tell me,” I said to the reflection, because he seemed more likely to answer than the blanket had all day.

Nothing. The mirror has a strict rule about only giving back what you give it.

The next morning, the list had a new line in my handwriting I did not remember writing.

— Anita / noon

I checked her phone again. Anita: Noon? I’m bringing coffee. Try and stop me.

I held the phone, then set it down as if it could go off accidentally and call someone who would require a story I wasn’t equipped to tell.

At eleven fifty‑seven, the doorbell rang in three cheerful bursts that made me hate my own chime. I cracked the door enough to let in a sliver of Anita wearing the kind of leggings you have opinions about and a denim jacket with enamel pins that said things like Nevertheless and Hydrate. She held two coffees like they were evidence in a case she clearly expected to win.

“Don’t panic,” she said, wedging her knee into the door as if there might be a dog. “I’m not going to kiss you. It’s not that kind of intervention.”

“She’s sleeping,” I said, which felt like saying the sky when someone asked about the weather.

“Then I’ll whisper,” she said, and slid past me.

Anita is the kind of friend who fills rooms with a convincing impression of competency. She landed at the edge of the couch, took in the blanket, the pillow, the barely there rise/fall, and rerouted the conversation like a driver ignoring a GPS.

“You’re pale,” she said to me instead. “And you look like you’re sleeping in your car again.”

“I didn’t—” I started.

She held up a hand. “It doesn’t matter. Drink the coffee that will keep your heart from stopping.”

I drank. It tasted like cinnamon and the way strangers’ kindness can embarrass you.

Anita talked for fifteen minutes about very little with the practiced ease of a woman covering for a friend at a party. Then she stood, leaned down, and put the lightest of touches on the blanket a foot from where my wife’s shoulder might have been under it. “Wake up soon,” she said to the pocket of air there. “You have a coupon for a foot massage that expires in May and I’m not wasting it on him.”

On her way out she stopped at the kitchen door, sniffed, and said without turning around, “You can’t mop grief away.”

“I know,” I said.

“You can try anyway,” she said, and shut the door behind her.

Late afternoon, a fly appeared out of nowhere in the hot square of sun on the coffee table and tapped at nothing like a tiny man testing walls for hollows. I watched it until I realized I was. I killed it with the list. When I peeled the paper back the smear looked like a punctuation mark at the end of things I’d written to myself: You forgot to get gas. You made a big decision after work today. You won’t forget about me. The fly made them look like a paragraph instead of a storm.

That evening, a thin, high sound woke me from a position that was terrible for my spine. It took me a quiet, concentrating second to understand it was my phone and then another to gather it from wherever I had set it last. Unknown number. I nearly let it go. I answered.

“Is this Mr. Garrison?” a woman asked, crisp.

“Yes.”

“This is Officer Ramirez with the police department,” she said, and a picture slid whole into my head: a woman with her hair pulled back and eyes that scanned rooms with a scanner that printed answers. “We had a call from your wife’s office expressing concern that she has not—”

“She’s here,” I said.

“—been answering her—”

“She’s asleep,” I said.

Silence. It stretched, then found a formal tone. “Would you be willing to do a welfare check with me on the line? Please try to wake her.”

“I’ve tried,” I said.

“Again, please.”

I put the phone on speaker and set it on the coffee table. I knelt. I put a hand on the blanket. The words felt sacrilegious and silly, like prayer recited by someone who does not want God to be real. “Hey,” I said, softly. “You have to wake up.”

Nothing. The blanket did not answer. The pillow made a sound like resignation.

“Mr. Garrison?” Officer Ramirez said. “Are you comfortable allowing an officer to stop by? Just to make sure—”

“I don’t want lights,” I said, and heard the line I had just drawn in the sand and loathed it.

“We don’t have to,” she said. “A quiet knock. If that’s easier.”

“Give me an hour,” I said. “Please.”

“Okay,” she said after a pause that was heavier than it should have been. “I’ll call you back.”

When the line died, the house had the gall to sound relieved.

I went to the bathroom and splashed water on my face and found a man in the mirror who looks like the understudy who had to go on because the star is sick. I said, to him, “You are going to fix this.” He stared at me until I stopped pretending I knew what that meant.

Back in the living room, the blanket lay in a way that made the shape beneath it undeniable to me in a way it had not been when there were still more days. At some point, the mind stops participating in the lie it wanted to love.

I knelt again. I slid my hand under the edge and found skin. It was not cool. It was not warm in a way the living are. It had the temperature the room gives you when you’ve decided not to argue with it anymore. The smell I’d been refusing to name braided tighter with the bleach waiting in its bottle like an old ghost of a different house. My eyes filled in a way that made my nose want to run, which was an insult on top of everything else.

Under the blanket my wife’s hair lay against the pillow. It was clean. I had washed it four days ago with a tenderness I had not known I remembered how to deploy. The pillow had yellowed around it the way wedding dresses do in attics, admitting the chemistry of time. Her face—when I made myself uncover it—was almost hers. Sleep has a way of making a person look like their best version sometimes, and death tries to copy it and gets the ratios mostly right if you don’t linger. Her mouth had relaxed into a line that could be mistaken for peace from two steps away. One eye had sunk more than the other, a tilt that would have made her furious with a camera.

I covered her again. I sat on the floor. I leaned my head against the edge of the couch the way a kid leans it against a dog.

“You won’t forget about me,” she had said.

I didn’t want to be the kind of man who needed to pour a bottle of something down a drain to make that sentence stop repeating. I didn’t want to be the kind of man who waiting an hour meant waiting until it is easier to lie. I didn’t want to meet the officer at the door with my hands smelling like the past.

I stood. I went into the garage. I picked up the bleach. It was heavier than it looked. I walked back to the kitchen and opened the cabinet under the sink and set the bottle there and shut the door with more ceremony than it deserved. Then I opened it again, took the bottle out, carried it to the trash, lifted the lid, and set the bottle on top of cereal boxes and the husks of vegetables I had let go soft.

From the living room: the faintest whisper of sound. Not a voice. A thready inhale? Or the house shifting into a new stance because I had moved a pawn?

I went back. I sat again. I took my list from the table and flattened it and smoothed the fly smear until it was just a shine. I added a new line.

— Call 911

Then, because I am the kind of man who needs some things to be plain, I wrote now beside it and underlined it three times.

The operator’s voice was the same voice it always is in crises—calm writ so large it looks like indifference if you don’t need it. I told her my address. I told her my wife would not wake up. I told her there was no point in telling her to hurry and she thanked me for not saying it. When I hung up, I put the phone on the coffee table face down beneath the remote as if I were putting a blanket on it, too.

While I waited, I went to the bedroom and did the two things I could: I made the bed, and I took the wedding album from the shelf in the closet where it had lived so long the air had a shallow groove for it. I brought it to the couch. I opened it to the page where we look like two people who have no idea how many versions of each other they are about to meet. I propped it on the armrest where her eyes would be, if eyes did what we wanted after we stop.

The knock came gentle, like a friend. The officer who stepped into our hall had dark hair and tiredness she wore like a belt. She looked at me, then at the couch, then at the mirror which had the decency to show her what she already knew.

“Mr. Garrison?” she said, and it was not really a question.

“Yes,” I said.

“May I?” She glanced at the blanket.

“Please,” I said, and for the first time in a month the word meant what it was supposed to.

She moved to the couch with a gravity that made me like her. She touched the blanket, then the wrist underneath it, then the air above my wife’s mouth. She did the thing with the two fingers on the neck that made me want to cry for reasons I could not explain. She nodded, once, to herself. She set a square of folded cloth on the arm of the couch because ritual is part of the job.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

“I’ve been sorry for a while,” I said.

She looked at the album propped where eyes would go. She allowed herself the smallest smile. “Good,” she said softly.

The paramedics came without the siren. They did their clean, efficient movements and I sat on the floor with my hands clasped between my knees like a student. When they brought in the stretcher I looked away not because I couldn’t bear it but because I wanted to give her the privacy she always hated me to violate. I looked at the wedding photo where I am squinting at the sun and she is laughing at something my uncle shouted from the table and tried to hear the laugh instead of the wheels.

“Do you have someone to call?” Officer Ramirez asked when the room changed shape again.

“I can call Anita,” I said.

“And your mother,” she added, and it landed as a mercy.

“I will,” I said.

She stood like a person at the end of a long shift who is not allowed to go home yet. “Do you have anyone to sit with you tonight?”

“I’ll be okay,” I said, and we both let the lie be gentle.

She nodded at the kitchen. “Smells like you were thinking about cleaning.”

“I was,” I said.

“You can,” she said, “but not the way you were going to.”

I huffed a laugh with no joy in it. “I put it in the trash.”

“Leave it there,” she said.

When they had gone and the door shut and the house did its old trick of trying on silence to see if it still fits, I went to the trash and pressed the lid so the hinge clicked. I took the list and folded it and slid it into the wedding album between the page with the cake and the page with the first dance where my hand on her shoulder looks like it knows what it’s doing because it practiced the night before in the kitchen until the utensil drawer jabbed me twice and she laughed and told me to either close it or admit I liked the bruise.

I made two phone calls. Anita answered on the first ring and cried in a way that made me sit down automatically because other people’s grief is heavier when you can’t hold it for them. My mother let it ring twice and then said hello like a person who already knows. I did not say the word bleach to either of them. I did not say smell. I said she’s gone and it was peaceful and come by in the morning and no, I’m all right and yes, I promise and love you and love you and then hung up and felt like a liar in the smallest, most human way.

I slept on the couch on the side that had not yet remembered the curve of her. I dreamed that she stood in the kitchen in her slippers holding a towel and scolded me for leaving water glasses beside the sink because rings on wood are a kind of sin. I dreamed that she said you made too much food again and took a bite anyway and said this is terrible and ate the rest and licked the fork, and in the morning the fork in the sink had a clean circle where the tines had been and I let the miracle be a miracle even though I know where circles come from.

I didn’t go into the garage for two days. When I finally did, it smelled like rubber and dust and faintly like a decision I had already made. The old bottle sat where I had left it on top of boxes that would go to the curb Thursday. I put it in a paper bag and drove it to the hazardous waste drop‑off like a man disposing of a prop after disbanding the theater company. The man at the gate had a vest and a clipboard and asked me Paints? Solvents? and I said Bleach and he said Left bin and I put it where he said and the lid thumped shut like a sentence.

In the weeks that followed, the house learned new tricks. The utensil drawer still had a taste for my hip, but less often. The mirror became less of a lake and more of a piece of glass. The smell diminished until it was something I could detect only when I let the room be still enough to be honest. It became, finally, what all houses smell like when they have been generously lived in—dust and heat and the underside of bread. Grief receded in the way it does—like a tide that is embarrassed to have been seen at high. It left behind lines on the wall you could trace if you wanted to remember how far it had reached.

I went back to work. I found the intern and said I was sorry in a way you cannot rehearse, not even with a list. He nodded and forgave me and I wanted to demand he make it harder and then realized forgiveness is not a performance for the forgiven. I took Anita to a foot massage place that did not take our coupon because the date had done the thing dates do. She laughed and called the manager and then paid anyway and called me impossible. My mother came on Sundays with soup and let me be the one who washed the bowls afterward. Officer Ramirez stopped by once at dusk, out of uniform, with a paper bag of tomatoes from a garden that had decided to forgive the weather. She looked at the couch and then at the wedding album on the shelf and nodded once like a person who has verified a fact she wanted to believe.

Sometimes, in the afternoons when the house leans its weight toward the west, I nap on the couch. Not the slack, shocked sleep of the first weeks. The kind of nap that is a gentleman’s agreement with the day. I wake to the smell of toast someone isn’t making and the sound of the upstairs neighbor’s door pretending to be mine. I sit up and say you left the utensil drawer open again out loud to no one, and it makes me laugh, and then I go and close it because some sentences need their verbs.

On the night that marked a month, I took the list from between the cake and the dance. I read it in the dim. The fly mark had dried to a dark comma. I found a pen and on the last line, beneath Call 911 now, I wrote Remember. Then, beneath that, Keep remembering. Then, because old habits have cousins, I added, Don’t buy that brand again and underlined it not because the bleach had power over me but because I have power over myself and sometimes that has to be on paper to be believed.

I put the album back. I stood at the window and watched the dark practice being night on our street. I could almost see the reflection of a woman in pajamas telling me something obvious I had done in a tone that was all affection and a little performance. I rolled my eyes and smiled at no one.

At some point, at some hour, I will start walking past the couch without smoothing the blanket. Not yet. I like the way it lays when I’ve touched it last. I like knowing where my hands have been.

On the morning of the second month, I woke to her voice again. Not a whisper from the couch. Not a sound in the wall trying out syllables. It came from a pocket of my head I had not let open for weeks.

“You left the utensil drawer open,” she said, fond as gravity.

I went to the kitchen. The drawer was open three inches. I closed it. I made eggs, badly, and ate all of them, and did the dishes right after like a person who knows you should. When I was done I stood there a long time and smelled nothing but the day.

I went back to the couch and sat with my knees pulled up like a boy. I put my palm on the blanket and felt the dent. It is the shape of goodbye and the shape of wait for me here. Both are true. I said it a last time because the mouth satisfies itself with repetitions the way the hand does with smoothing.

“I won’t forget about you.”

The house listened. The drawer stayed shut.

The smell didn’t come back.

When I dreamed that night, it wasn’t of the garage or the drain. I dreamed of a drawer closing all the way the first time. I dreamed of a list with one line, in her handwriting and mine together:

— Remember me.

In the dream I underlined it twice. When I woke, I did, too.

END!

News

I stole my own identity and I think my family is getting suspicious.

Part 1 It was late September when I came home. The sun was angling low through the sugar maples on…

We tried summoning a demon as a joke. But something answered.

Part 1 I didn’t believe in any of it. Not really. Demons, rituals, salt circles… all that stuff felt like…

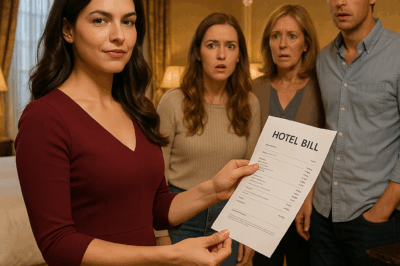

They Mocked My Tiny Apartment—So I Booked Them a Luxury Hotel… Then Left Them the Bill

Part 1 I always thought I was a patient person. Turns out seven years of being married into Thomas’s family…

Parents Took My College Fund for My Brother’s Startup, Then Refused to Pay Me Back

Part 1 I always knew the exact moment I decided to destroy my family. It wasn’t when they drained my…

They Lied About My Illness For 25 Years To Fund My Sister’s Life

Part 1 I haven’t been allowed to drive alone since I was sixteen. Not because I’m a bad driver—no one’s…

Forgotten at Dad’s Birthday—Until I Forwarded That Email

Part 1 I stared at my phone, fingers trembling as I scrolled through the Instagram photos. There they all were—Mom,…

End of content

No more pages to load