My Stepfather Called Me a Maid in My Own Home — So I Made Him Greet Me Every Morning at the Office

Part One

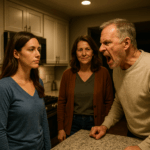

The plates felt heavier the night he said it. I was stacking them at my mother’s Christmas party, balancing a precarious tower of porcelain while laughter and clinking glasses swelled around me. I’d grown good at being invisible in rooms full of people who mattered to other people. I learned to make myself small when attention threatened to expose something I had no language for yet—my hunger, my stubbornness, the ache of being underestimated.

“Get back to the kitchen,” Richard Bennett said, loud enough that half the room turned. He pointed at me with that slow, theatrical smirk like he’d just delivered the evening’s punchline. “The maid doesn’t need to stand here.”

It was a ridiculous thing to say—ridiculous and cruel—but the absurdity didn’t make it less sharp. My cheeks flushed hot, but not from shame. The heat was fury, a small, combustible thing that ignited and refused to die. I could have sunk beneath the insult, folded into the role he assigned: the grateful stepdaughter who scrubbed and smiled. I could have chosen the easy, long-accustomed obedience. Instead the words became an ember I tucked in my pocket.

By the time I was thirty, I’d learned how to let that ember burn into a plan.

Growing up in a small Tennessee town, my earliest memories were of needlepoints and the hum of a Singer sewing machine in my mother’s tiny shop. Susan Mitchell worked her fingers raw to keep a roof over our heads after my father left when I was seven. We paid the bills with hems and hems again, with scarves and small alterations that kept regular customers coming back. Money never sat comfortably with us, but there was pride. There was always the sense that work ought to be honest and visible in the seams.

At fifteen I started taking odd jobs—folding clothes at a thrift store, pouring coffee at a diner, sweeping floors after school. The world I imagined for myself had no room for being owned by anyone. I wanted a future that belonged to me. I concentrated on school like it was a job in itself and earned a scholarship to the University of Tennessee. The scholarship covered some of it. The rest I bankrolled with shifts and freelance web work that began as a hobby and turned into a skill I couldn’t ignore.

When my mother married Richard, it felt like someone had come to fix the roof for once. He arrived with city polish, a tailored coat, and a laugh that filled rooms he bought with business lunches. He brought the promise of stability—paid-off debt, a condo in the city, easy dinners. For my mother, who had worked for decades, it looked like reprieve. For me, it introduced an unfamiliar tension: the stepfather who smiled a lot and demanded more of my patience than he ever gave.

At first I told myself I was lucky. We moved into a nicer life, and my gigs in tech paid off enough that I could afford my own apartment in Chicago later. But “luck” was a thin veneer. Richard’s little jabs—comments about my thrift-store blazer, his casual requests that I fetch his coat—arrived at the joints, undermining quietly. He’d ask me to pour wine when guests came, to clear plates as if this condo had employed a staff whose place I happened to occupy. Jennifer, his daughter, never lifted a finger. She’d amuse the room with curated laughter and disposable jabs at “my cute ambition.” My mother’s silence was the loudest thing of all. She would look down at her hands and pretend none of it mattered.

I promised myself the quiet life of compromise was temporary. During late nights, after double shifts and bars of bad coffee, I coded. Little freelance sites, ad optimization experiments, examples of campaigns that would later pull in real money. Code became a place I could build and be measured for what I produced, not for how well I scrubbed a table.

The breaking point came on a night that should have been ordinary. Richard’s Christmas party was one of those glass-and-candle affairs where his professional friends praised his deals and his house looked like an advertisement for success. I arrived early to help, arranging platters and pouring wine for my mother because she insisted on being hostess without the heart to do the work. I’d been trying—every visit—to be the daughter who kept peace.

He announced it as if he were handing out awards. “The maid doesn’t need to stand here,” he said, pointing at me and laughing. The room held its breath, polite surprise peeking through. I set the plates down carefully. I met his eye. “I’m not your maid, Richard,” I said, and there it was: the line I had spent years rehearsing to myself. He brushed it off as a joke, but his face had already stiffened. I felt something loosen inside me—a strap snapping.

That night I didn’t cry. I drove back to my small apartment and started a new file called Mitchell Analytics. The seed had been there for months—an idea for a personalized ad platform that fundamentally changed how campaigns targeted real people. But anger is a fuel that sharpens focus. I opened a blank editor, started sketching algorithms, writing pseudo-code, sketching a pitch in five bullets: personalization in real-time, machine learning that learned from conversion at scale, easy integration for mid-market brands. It read like a wish list until I started building it into something that worked.

Lisa Morgan, my roommate and my rock, listened without judgment. “You built this life on grit,” she said, pizza grease on her fingers. “Start acting like it.” She became my co-conspirator. We worked nights, pitching small clients and writing code, doubling down on what we did best. I taught myself to speak investor language: TAM, CAC, LTV. It was a new vocabulary for a girl who once counted quarters for bus fare.

Chicago was a hungry place for anyone willing to work. I registered for conferences I couldn’t really afford, wore off-the-rack blazers that cost more than I liked to admit, and clutched my deck while my heart tapped like a nervous animal. I met Karen Walsh at one such event—a venture capitalist with a voice like a bell. She’d started a fund after clawing herself out of a marriage that had boxed her in. She listened to my early prototype, asked brutal questions, and when I left the meeting her card smelled like possibility.

With Karen’s mentorship, Mitchell Analytics began to breathe. She connected me to investors and engineers. I hired Mark, a young data scientist whose algorithms made our system sing. I spent nights debugging and days pitching. We went from scrappy prototypes that pulled in $5,000 ad engagements to a platform that managed millions of impressions. Revenue trickled in and then coursed like a stream. Each milestone was a brick in a wall I was raising around the life I would finally own.

Then Rebecca Hol, a tech journalist digging into the media industry for a piece, gave me a file she’d found through reporting into Bennett Media Solutions—Richard’s company. Their numbers looked like a house of cards. Mismanaged accounts, desperate loans, and internal emails that smelled of panic. If a single piece of that company’s value could be salvaged and restructured, it would be worth more than anything Richard had ever thought to hoard. I showed Karen the documents. She didn’t laugh. She asked for the numbers, for the stress tests, for a plan to execute a takeover with a soft touch. Phoenix Partners, a shell acquisition outfit Karen trusted, could front capital if I could gather matching funds that convinced other investors. Her belief turned the ember into a roaring plan.

We raised the money, shuffled documents through lawyers who had long practiced the art of corporate camouflage, and structured a $35 million acquisition that didn’t carry my name across the front page. Phoenix Partners became the majority owner of Bennett Media Solutions, and I—Sarah Mitchell, the “maid” from the Tennessee shop—hosted the staff meeting for the first time not as a guest but as the strategist meant to save the company. I walked into a boardroom with glass walls and a scent of expensive leather, and Richard was in his element at the head of the table.

For him there was an awkward moment of disbelief. I sat at the back at first, feeling both the tremor of the past and the coolness of the present. “This is a closed session,” he barked. “What are you doing here?” My voice didn’t rise. “I’m here on behalf of Phoenix Partners. We’re the new majority owner.” A silence fell. The board shuffled papers. He stared at the documents while the room rearranged itself around a truth he had not predicted.

I laid out a plan—operational changes, tech integrations, staff augmentations. I wasn’t there to humiliate him; I was there because his failure risked the livelihoods of the people who worked for him. But yes, I’d thought long about what a symbolic gesture would feel like. I wanted him to understand the power dynamic had changed. “He’ll greet me at the office from now on,” I said, and the room inhaled. It was a small, deliberate line that tasted like victory because it was more than petty. It mattered because it made a point: I owned what I had built. He would not be allowed to reduce me again with a joke in front of an audience.

He tried to scoff. Jennifer tried to scoff louder. The board didn’t laugh. They asked about the timelines and the revenue projections instead. Numbers, not slights, forced the room’s attention. Mitchell Analytics had a few clients, yes, but it had precision, and when Karen and I connected it to Bennett’s existing back-catalog, the new offers looked profitable. The board nodded. The acquisition was real.

When the day I had planned for months came—my reveal, my formal stepping into the managers’ circle—I watched the man who once owned my nights and smirked at my mornings shrink into someone who now reported into a system I supervised. The morning after the legal filings were final, I arrived at the office to a staff coffee bar and a humming open-plan layout that felt strangely domestic for a corporate space. Richard was at the doorway, paused, and then did something I had only imagined: he said, “Good morning, Ms. Mitchell.”

It was clipped and formal. His jaw was tight. But he said it. In his voice there was no warmth; there was a careful, measured compliance. I held a mug, smiled politely, and felt a wash of something like relief. The power that had been held over me—public humiliation leveraged as private control—had been reorganized into a professional relationship where the terms were clear. Nothing about the way he’d spoken to me before was excused in an office where someone else held the keys.

That was the immediate, visible victory. But victory itself is only a hinge. The real work was just beginning: changing a company culture that rewarded bluster and punished quiet competence, proving to people inside and outside that a woman from a sewing shop could run an empire’s rescue without breaking her edges. I drank coffee, worked through product rollouts, visited client sites, and in meetings rewired conversations that had once been Richard’s safe turf. The smile I felt was quiet and private. It belonged to the small Tennessee girl who’d learned to sew and later learned to code.

Part Two

Power feels different when you’ve earned it by building instead of by birthright. The months after the takeover were a whirlwind of travel, meetings, hires, and policy rewrites. We stabilized accounts, restructured ad packages, and rescued three clients who had been on the verge of leaving. We retooled Benson’s internal pipeline and introduced a code of conduct that made “respect” a stated business principle. There was pushback from old guard execs who resented a younger woman telling them how to do their jobs, but when the numbers improved, the critiques quieted.

Richard, predictably, resisted. He continued to show up each morning at the office, but his posture was different. He moved through his day with the air of a man twice his age who’d been taught patience the hard way. Sometimes he’d force a “Good morning, Ms. Mitchell.” Other times he’d snarl something under his breath and retreat to his old office, the walls papered with framed headlines of former glory. He had pride enough to keep his mouth closed to the press, but not enough to muster humility.

One of the first big decisions I made was to change how we evaluated success. Bonuses would be tied to team results, not to a single executive’s ability to charm clients. We launched training on communication and bias, making sure junior staffers had a path to rise without being able to be sabotaged by gossip. I’d watched men like Richard practice a certain theatrical dominance for so long it felt institutional. The antidote was building structures that rewarded good work and muting the theatrics that led to abusive workplaces.

Outside the office, life changed in quieter ways. I moved to Seattle with Lisa and Mark. The mist there felt like a new skin. We found a loft that let sunlight in through big windows and planted succulents that stubbornly refused to die. My mother reached out in a slow, crooked way—letters instead of calls—apologizing for the years she’d hidden in silence. The letters asked for forgiveness and offered excuses. I read them carefully, because forgiveness isn’t a single act. It’s a sequence of small, deliberate choices. For now I chose distance, not rejection—a line I drew to keep myself whole.

Jennifer’s presence receded into the background of my life. She tried a phone call once that was more accusation than reconciliation. “You stole Dad’s company,” she hissed. I listened and then said nothing. Hanging up felt like the only answer worth giving. There are fights you don’t win through words, and this was one of them. Her anger was loud but not enduring. Time, as it does, softened her edges in its own way. She faded; Richard remained a professional fixture who performed greetings when PR demanded it.

I channeled my energy into Mitchell Analytics and into the philanthropic thread I’d been nurturing quietly. The Mitchell Foundation began as a small seed of an idea: give entrepreneurs from first-generation backgrounds a leg up. A year after the acquisition, we launched the first cohort funding program, offering not only grants but mentorship, office hours, and a community that could prevent the isolation I’d known for years. Watching founders pitch in a room where I’d once felt out of place was one of those small, sharp satisfactions that leave a warmth rather than a hard pride.

Richard’s world did not crumble dramatically. He kept a title for a while and took his dignity to the boardroom in the mornings, but the moral of the story wasn’t to watch him fall. He paid restitution in professional terms—his legacy re-cast to be less about the man and more about the product he’d once led. I sometimes wonder what occupied his nights: regret, twitchy resentment, the slow unavailability of certain audiences. He might have gone on to reinvention, or he might have stayed trapped in a loop. Either way, my life had moved beyond his rhetoric.

The takeover brought other, unexpected consequences. Reporting on the acquisition drew attention from journalists who wanted to know how a young woman had orchestrated such a coup. Rebecca Hol wrote a piece that handled the event with nuance, noting that this was not just taking power but reshaping it. She interviewed staffers who had seen morale climb and invited critiques from experts about the ethics of acquisitions that remain economically tidy but socially risky. The conversation made our work sharper. It forced me to take responsibility for the outcomes my decisions caused. Power, I learned, looks good on paper, but the real moral test was in the messy details: who gets hired, who gets promoted, who is safe in their workplace.

I found myself returning to Tennessee more than I had expected. The sewing shop was still there in my memory—my mother’s hands, the steady tick of a machine. Visiting my hometown was like walking through a museum of who I had been. I sat in the local diner sometimes, listened to strangers, and found little stories of people trying to start businesses, to keep farms afloat, to send kids to college. Those visits fed the Mitchell Foundation. We started a satellite program that funded scholarships for technology education in rural areas, partnering with community colleges.

Building a philanthropic wing was less glamorous than the acquisition and more fulfilling in a way that grounded me. At the first Mitchell Foundation cohort showcase, a woman from a town with a population of two thousand pitched an app that connected elderly neighbors with young volunteers. She won a grant and cried. I did too, quietly. Those moments healed something the boardroom could not.

Love arrived neither as a rescue nor as drama, but as something patient. Jonathan—no, he was not the romantic fairy-tale the movies promise; that part of my life had been messy and human long before the acquisition. Instead, my closest relationships bore the marks of steady companionship: Lisa, who’d been there when code crashed and when funding called; Mark, who’d learned to be a leader in an office that asked him to be humble; Karen, who lent not only capital but an unflinching clarity that became a model for how I made deals. These were the people who formed the soft skeleton of my life.

Sometimes, in a quiet office late at night, I’d find a folded note from my grandfather in a drawer, a scrap where he’d written in his careful hand about how money should be used to make people’s lives better, not to prop up one man’s ego. I kept those notes as a counterweight to the ledger books and trademark filings. They reminded me of a ledger that truly mattered—the one that recorded the difference you made in people’s lives.

Years after that Christmas party, someone asked me at a talk: was it revenge? I considered the word and answered that revenge is narrow and hungry, an act that seeks satisfaction through another’s pain. What I did was different. I built. I reshaped. I turned humiliation into a blueprint for something that didn’t simply push him down — it raised a structure that others could rest in. If he learned to greet me properly in a morning meeting, that was a visible sign of changing norms; if he learned to check his assumptions at the door and treat a colleague—myself—with professional courtesy, that was better for the people working under him. Bringing dignity into a workplace can be radical.

Of course the old scripts don’t vanish. On some mornings Richard still looked at me as if I were an irritant he had to tolerate. Sometimes he was mean in ways that didn’t make the press—sharp emails, passive aggressiveness, attempts to undermine ideas he hadn’t understood. I handled those not with theatricality but with policy: escalation protocols, HR training, transparent processes that made personal vendettas irrelevant. Structure is a kind of kindness in a place where people’s livelihoods depend on not being bullied.

There were times I missed simple things: the ease of being invisible, or the lack of responsibility for other people’s livelihoods. But the trade-off felt right. Responsibility gives you the chance to change the course of a few lives. I remember the first Thanksgiving when members of my old hometown came into the Seattle office, new hires and grantees and a few investors who had become allies from small towns themselves. We passed dishes on long tables and told stories about small shops and the perils of city lights. The conversation was richer than any boardroom victory.

The Mitchell Foundation’s impact scaled, and so did the company. We innovated ad algorithms responsibly, woven with privacy protections by design—because the same technology that targets can also respect. As we grew, I thought about the little girl who stitched hems beside her mother and wondered how many small towns had girls bending over machines, dreaming quietly. The foundation’s role wasn’t to fix every inequity, but to stitch together opportunities where none had been available before.

When people ask how it felt the first time Richard actually smiled—real warmth, not a publicist’s mouth-shape—at a company milestone I remember shrugging. It wasn’t about him. It was about me watching a system shift. I noticed small changes over the years: staff that once whispered in corners now spoke up at meetings; junior employees who had once exited jobs with a bitter taste were retained with clear career paths. The ripple effects mattered. It became less about the man who had called me a maid and more about the people who could now work in a space that had a different memory.

And yet, the past had its way of visiting in odd ways. A man who had once prided himself on being self-made—on his ruthless deals and cutthroat reputation—was a quieter figure now. He called once to ask advice, as if humility had finally wrapped around him like a surprising coat. I answered with a boundary. Advice without apology felt untenable. If he wanted to be part of the new culture, he would have to step into it with respect, not demands.

The years folded into routines: investor meetings, product demos, foundation applications. I learned how to be a public figure without letting it define me. I accepted invitations to speak at conferences and used those platforms to talk about ethical modeling, about how power behaves in boardrooms, and how technology could be a lever for justice when built with care.

A decade after that brutal Christmas remark, I sat on a small stage at a university event, the kind of place that made me remember my first classrooms. A young woman came up after the talk and handed me a hand-lettered note. “My boss told me I should accept being small,” she whispered. “I found your talk, and I quit the next week.” We cried together in the greenroom. Those were the moments I saved up for, not headlines and not morning greetings, but the quiet, stubborn acts of someone choosing themselves.

If you ask whether I hold anger, I’m honest: for a while, yes. Anger is energy and a clarifying force when directed at rebuilding. But it had to turn into something else: strategy, policy, funding. I built courses to teach financial literacy in Rust Belt towns and created scholarships for women who wanted to learn to code. I invested in people and in protocols that made abuse less profitable and resistance more possible.

There is a quiet joy in the life I made. I grow plants that live now, not succumbing to neglect. I have friends who keep each other honest and celebrate without measuring returns. I put my mother’s old Singer sewing machine in a window at the foundation office as a reminder that everything meaningful is made stitch by stitch. Susan calls sometimes. Her voice is softer now. I meet her for coffee on neutral ground when it feels right. Our relationship is a work in progress—like every important thing I’ve built, it takes attention.

And Richard? He still greets me sometimes. He still sits in an office he helped create. He’s not the villain of a melodrama; he’s a man who had power and let it shape him poorly. The message I gave the room that night years ago has been rewritten: power without accountability is fragile. Accountability without cruelty is powerful.

So when people ask whether I wanted him to bow, or to choke on his smirk, I answer that I wanted something better: a change that would ripple beyond our awkward family dinners. I wanted a world where girls in small towns could build products without being reduced to their station at a table. I wanted a culture where “maid” was never a term used to diminish a person’s worth.

That morning in the Bennett office, his greeting was a formality. He said, “Good morning, Ms. Mitchell,” and I watched him choose a word that acknowledged my place at the table. The rest was work. I trained teams, rewired incentives, and mentored founders. I taught people how to use technology without losing their humanity. Every time a junior employee told me they could finally breathe at work, I felt the old ember bloom into something warm and lasting.

My life is not a tidy triumph, it’s a long resourceful poem. I still remember making the plans at midnight in a small apartment. I remember the taste of cheap coffee and the feeling of being underestimated. Those memories are not wounds; they are textbooks. They taught me a lesson I try to pass on to every entrepreneur who walks through the Mitchell Foundation doors: the world will underestimate you—let it. Use the energy that misjudgment gives you to build something honest. Build structures that protect others from the way you were treated.

In the end, it wasn’t about making him bow to me in the petty way I once imagined. It was about changing the conditions in which those words had power. I made him greet me every morning not so he would feel small, but so he would feel the weight of his choices in a place where respect had been redefined by action, not by a title. The hardest part was not the takeover or the negotiations. The hardest part was remaining kind enough to use the power I’d fought for to create space for others.

If the girl who threaded needles in my mother’s shop could look at the woman I am now, she’d see a table where everyone can sit—if they’ve earned the seat through work and humanity. That is the closure I wanted: not the humiliation of a stepfather, but the creation of a world where humiliation does not decide who gets to speak first. I still drink too much coffee sometimes, and I still knock the occasional pot off the stove, but when I walk into an office or a classroom or a small-town diner now, I carry a quieter confidence. It doesn’t need a greeting to validate it.

And sometimes, on early mornings when the city is still drifting awake and the light hits the Puget Sound in a forgiving way, I smile at the memory of a Christmas party and the ember I tucked in my pocket. It lit not just my life, but the lives of people I will never meet. The greeting at the office became a metonym for a larger change: one woman’s refusal to be small, built into policy and funding and the slow work of remaking a culture. That change, finally, feels like the kind of answer worth giving.

My Stepfather Called Me a Maid in My Own Home — So I Made Him Greet Me Every Morning at the Office

Part Three

The first time protesters gathered outside our glass building, I watched from the sixth-floor window and felt a familiar heat crawl up my spine. Different city, different room, same sensation: a crowd, a judgment, my name in someone else’s mouth.

They held cardboard signs with sharp black letters.

STOP PREDATORY TARGETING

YOU SOLD OUR PAIN FOR CLICKS

MITCHELL ANALYTICS = SURVEILLANCE

At street level, they looked small. On social media, they were enormous.

It started with an investigative podcast. A young journalist, hungry and relentless, traced how one of our mid-tier clients had used our platform to target ads for high-interest loans at neighborhoods already drowning in debt. The client had done it by exploiting a feature we’d built for “hyperlocal personalization.” Technically, they hadn’t broken our terms. Morally, they’d ripped them to shreds.

They named us. Not Richard’s old company. Not Bennett Media. Me.

Mitchell Analytics.

In the episode, the journalist described an older woman in Cleveland who’d clicked on one of those ads after her hours were cut at the grocery store. She took a loan to cover rent. The fine print ate her alive. She cried on tape, voice cracking on my morning commute as I sat parked in the garage, hands frozen on the steering wheel.

“I thought they were helping me,” she said.

Her words carved straight through the armor I’d built.

Mark knocked on my car window as the episode faded into an ad read. I jumped. He opened the passenger door and slid in, his expression tight.

“Listened?” he asked.

“Yeah.” My voice sounded thin.

“We flagged that client last quarter,” he said. “Compliance sent a warning. They danced just inside the lines.”

“Lines we drew,” I said.

He didn’t argue. He didn’t flinch. That’s why I trusted him.

We took the elevator up together, the two of us reflected in polished metal: me in a navy blazer and scuffed boots, him in his eternal hoodies. On the sixth floor, Lisa was already in my office, eyes on a tablet, jaw clenched.

“They’re calling,” she said. “Press, board, three senators’ offices. And Karen.”

“Of course Karen,” I murmured, shrugging out of my coat. “Let’s get ahead of it.”

We spent the next eight hours in a war room we hadn’t planned to need. Legal sat in one corner, HR in another. PR occupied the space between, like nervous connective tissue.

“There’s no legal liability if we can prove we acted in good faith,” the general counsel, Eugene, said. “Our policy doesn’t explicitly permit this kind of targeting, but it doesn’t explicitly forbid it either.”

“That’s the problem,” I said. “We built something abusable and trusted people not to abuse it.”

“Sarah,” the PR head, Ari, said carefully, “if we start from a place of self-flagellation, we’ll be eaten alive. The board is already on edge. They want to know we’re defending the company, not throwing it under the bus.”

I thought of the woman in Cleveland, of her voice shaking over my car speakers. I thought of my mother staring at late notices on the kitchen table, running her thumb over numbers that did not add up. The anger I used to carry like a stone in my pocket stirred.

“We are not under the bus,” I said. “We are driving. If we hit someone, we don’t blame the road.”

The room went quiet.

“Okay, then,” Lisa said, stepping in smoothly. “We need a plan that actually aligns with that. Not just a statement. A course correction.”

We drafted until my eyes blurred: a moratorium on certain types of hyperlocal targeting, an immediate termination of the contract with the loan client, a commitment to build a new ethics review board with outside voices, not just our own. We argued over verbs and clauses and then over the actual substance behind them.

In the middle of it all, my phone buzzed silently on the table, over and over. Finally, between calls, I glanced down.

Three missed calls from “Mom.”

A text, short and uneven: honey call me please. hospital.

The room blurred at the edges. Sound drained down to a thin whistle.

“Lisa,” I said, and she knew from my voice. “I need to go. Now.”

Her eyes flicked to my screen and then back to me. “We’ve got this for a few hours,” she said. “I’ll loop Karen in, keep the board from combusting. Go. Planes exist.”

An hour later, I was buckled into a narrow seat, fingers digging crescents into the armrests as the plane shuddered up through clouds. Reports and drafts lay abandoned in my email. The only thing that mattered was the hospital name my mother had typed with trembling fingers.

Tennessee air felt thicker when I stepped out of the airport. Humid, familiar. It smelled like honeysuckle and asphalt and a childhood I’d spent trying to claw my way out of.

At the hospital’s front desk, I barely remembered my own name. “Susan Mitchell,” I said to the nurse, too loudly. “She texted. She said hospital. I’m her daughter.”

They pointed me to the cardiac floor.

I walked down a corridor lined with pale blue walls and antiseptic shadow. Fluorescent lights hummed overhead like tired insects. My heart hammered so hard I felt it in my ears.

When I reached my mother’s room, I stopped.

Through the glass, I saw her—smaller than I remembered, hair thinned, wires trailing from her chest to a monitor that beeped a slow, stubborn rhythm. And sitting in the visitor’s chair, elbows on his knees, gray at the temples and hollow-eyed, was Richard.

He looked old.

Not in the way people joke about feeling old after a long week, but in the way a tree looks after too many winters. His shoulders sagged under a jacket that no longer fit right. The lines around his mouth had deepened into canyons. On his face was something I’d never seen there before: unvarnished worry.

For a moment I just watched them. My mother’s hand lay limp in his. His thumb brushed her knuckles with a tenderness that startled me.

A part of me wanted to turn around, to slip back into the hallway and never let him see how my stomach twisted. But that was the girl who learned to make herself invisible. The woman who ran companies did not retreat because someone occupied a chair.

I opened the door.

His head jerked up at the sound.

“Sarah,” he said, standing so fast the chair scraped the floor. Two syllables, naked and startled.

“Hi,” I said. My voice came out thin. “How is she?”

He glanced at my mother, then back at me. “They say it was a mild heart attack,” he said. “Stents. Monitoring. She keeps scolding the nurses for fussing over her.”

That sounded like her. Relief hit so suddenly my knees almost gave.

I moved to the other side of the bed and took her free hand. It was warm, thank God. Her eyes fluttered open.

“There you are,” she murmured. “I told him not to bother you. You’re always so busy. Saving the world.”

Even in half-consciousness, she found a way to minimize her own crisis.

“There’s Wi-Fi in Tennessee,” I said softly. “And planes.” My throat closed. “You scared me, Mom.”

She squeezed my fingers weakly. “You always were dramatic,” she whispered, and a faint smile tugged at the corner of her mouth.

A nurse came in and shooed us gently. Rest, she said. Come back in the morning. As we stepped into the hallway, the door clicked softly behind us, leaving me alone with the man who had once called me a maid in front of a roomful of people.

The silence between us was thick.

He cleared his throat. “Thank you for coming,” he said.

“Of course I came,” I replied. “She’s my mother.”

“I meant…” He stopped, rubbed a hand over his jaw. “Never mind.”

We stood side by side, watching the rhythm of strangers’ lives through the open doors along the hall. Machines beeped. Nurses moved like practiced ghosts.

“How bad is it?” I asked.

“Bad enough that they’re talking about lifestyle changes,” he said. “Medication. No more sixteen-hour shifts at the shop. Not that she listens.”

Somewhere under the worn sarcasm, I heard fear.

A memory flickered: my mother pressing a cold washcloth to my forehead when I had the flu at eight, insisting she was fine while she swayed on her feet; Richard at the head of a Christmas table, telling me to get back to the kitchen. Two different versions of care and control, tangled together.

“Do you need help with anything?” I asked, the words surprising me.

He looked at me sharply, as if I’d set a test in front of him without warning.

“I…” He faltered. “Your foundation. The travel. The… scandal.” The last word tasted bitter in his mouth. “You’ve got your hands full.”

“You still read the business pages, I see,” I said.

He gave a humorless huff. “Hard to avoid, when your stepdaughter’s face is on them.”

There it was: the old barb, dulled by exhaustion but still sharp.

“I’m handling it,” I said. “We made mistakes. I’m fixing them.”

He stared at me for a long moment, eyes glittering in the harsh hospital light. “I heard your statement,” he said finally. “On TV. You took responsibility. I never saw anyone in my generation do that unless the lawyers made them.” He paused. “You did it anyway.”

I shrugged, uncomfortable. Praise from him felt like a jacket borrowed from a stranger: ill-fitting, hard to wear.

“It’s my company,” I said. “My name. I don’t get to pretend I’m just the help.”

The words hung between us like a challenge. His jaw tightened.

“You never were,” he said quietly.

I almost missed it. Almost.

“What?” I asked.

He looked away, down the hallway, as if he could slip the confession past me without eye contact. “You were never just ‘the help,’” he repeated. “I was… an ass. Back then.”

An apology, crooked and incomplete, but more than I’d ever gotten.

“Back then?” I said slowly. “Richard, you called me a maid in my own mother’s house. In front of your friends.”

He winced, as if the sentence itself hurt. “Yeah,” he murmured. “I remember.”

“Do you remember how old I was?” I pressed. “How much I depended on that roof?”

He flinched again. “Old enough to talk back,” he said, but there was no heat in it.

I took a breath, forced steel into my voice. “I built an entire career out of that night,” I said. “Out of what you said. You don’t get to round it down to ‘back then’ like it was a bad haircut.”

He nodded once, slowly. “You’re right,” he said. The confession scraped on the way out. “I was cruel. I thought… if I made you small, it would make me bigger. It’s what men like me were taught.”

I stared at him. The hallway hummed. Somewhere a monitor beeped faster, then slower again.

“Is this you asking for forgiveness?” I asked.

He swallowed. “This is me telling you I know I don’t deserve it,” he said quietly. “But I’m… sorry. For the maid comment. For all of it.”

The words were not dramatic, not accompanied by tears or sweeping gestures. They were small and plain and heavy. The kind of words you say when your wife is behind a door with machines making sure her heart keeps beating.

For a long moment, I said nothing. The girl inside me who’d waited years to hear those words paced like a caged animal. The woman I’d become knew better than to mistake apology for transformation.

“I hear you,” I said finally.

He exhaled, shoulders dropping a fraction.

“That doesn’t make it okay,” I added. “It doesn’t erase anything. But I hear you.”

He nodded.

“That’s more than I deserve,” he said.

We both looked back at my mother’s door then, as if the woman in the bed could somehow arbitrate between us. Maybe she was the only one who ever really could.

“I have to get back to Seattle tomorrow,” I said. “The company—”

“Of course,” he said quickly. “Of course. I’ll stay. I’ll make sure she doesn’t bully the nurses into discharging her early.”

We shared the faintest ghost of a smile. For the first time, we laughed at the same truth instead of at each other.

“I’ll send someone down to help with the shop,” I said. “We have grantees who’d kill for retail experience and a chance to live somewhere quieter for a while. They can keep the place open while she recovers. No one gets to tell her she has to close if she doesn’t want to.”

“You’d do that?” he asked, surprised.

“Of course I would,” I said. “I owe that Singer machine more than most investors in my cap table.”

He chuckled, the sound rusty.

“Your mother will fight you on it,” he warned.

“She can shout at me with a healthy heart,” I replied. “That’s a fight I’ll take.”

He nodded, and for the first time in our long, twisted history, we stood together for a moment on the same side of something: wanting Susan Mitchell to live.

On the flight back home the next day, I listened to the podcast episode again. This time, when the woman in Cleveland spoke, I didn’t just hear her as a victim of my product. I heard her as my mother, as any person trying to catch their breath in a world built to keep them gasping.

By the time the plane landed, I knew what I had to do.

Part Four

The emergency board meeting was already in full swing when I walked in, duffel bag still slung over my shoulder. Sleep clung to my eyes like a bad decision. My blazer smelled faintly of hospital disinfectant.

“We were just discussing your statement,” one board member said as I took my seat. His name was Michael, one of the old guard holdovers from the Bennett era, his tie as tight as his jaw. “Some of us feel it was… overly self-incriminating.”

“Some of us,” another board member—Amira, a newer addition I’d personally vetted—countered, “think it was the first honest CEO statement we’ve seen in years.”

Karen sat at the far end of the table, fingers steepled, watching me with that calm, assessing gaze that had once felt like an interrogation and now felt like an anchor.

“Welcome back,” she said.

“Thanks,” I said. “Update on my mother: she’s stable. Angry, which is probably the best sign.” A ripple of polite chuckles eased the tension. I let it pass, then leaned forward.

“I listened to the podcast again on the way here,” I said. “Our platform made their targeting possible. The client made the choice to exploit people. Both are true. Here’s what I propose.”

We spent the next hour hitting the bones of the plan I’d sketched on the plane: independent ethics board, profit-sharing with communities harmed by exploitative campaigns, a new set of hardcoded constraints in our product that would make certain kinds of targeting impossible, even if a client begged.

“It will cost us,” Michael said flatly. “That loan company alone accounted for eight percent of last quarter’s revenue.”

“If our business model depends on squeezing people in crisis, it’s a bad business,” I said.

“We’re not a charity,” he snapped.

“No,” I agreed. “We’re not. But neither are we a loan shark’s favorite knife.”

A low murmur ran around the table.

“You’re talking about reorienting the entire company around a moral stance,” another board member said cautiously. “That’s… ambitious.”

“Building this company was ambitious,” I said. “So was the acquisition. We did those. We can do this.”

“And if we don’t?” Michael pressed. “If we continue as is, with improved messaging and a few cosmetic changes?”

“Then we become the story every investigative journalist salivates over,” I said. “We lose talent. We lose trust. In ten years, we’re a case study in what not to do.”

Silence, again. For a moment, the only sound was the soft whir of the HVAC and the muted city beyond the glass.

Karen finally spoke.

“Mitchell is right,” she said, and the room shifted almost imperceptibly toward her. “Markets change. Consumers are not as blind as they used to be. Regulation is coming, whether we like it or not. Getting ahead of it is not just ethical—it’s strategic.”

She turned to me, eyes sharp. “But,” she added, “you know there will be blowback. From investors who want quarterly gains over long-term resilience. From clients who will threaten to leave.”

“I know,” I said quietly. “I’m prepared.”

“Are you prepared,” Michael interjected, “for us to have to consider new leadership if this goes badly?”

The threat hung there, sticky and real.

I thought of my mother in her hospital bed, of Richard’s bowed shoulders in the hallway, of the Cleveland woman’s voice cracking on tape.

“Yes,” I said. “If I lose my job because I refused to profit off pain, I can live with that. If I keep it by looking the other way, I can’t.”

Karen stared at me for a beat and then smiled, a small, fierce thing. “Well,” she said, “I know which headline I’d rather be associated with.”

We held the vote two days later. It wasn’t unanimous. It was enough.

The ethics overhaul rolled out over the next year like an internal earthquake. Some clients left. Others stayed and adjusted. New clients came specifically because of the stance we’d taken, attracted by the combination of sharp tech and clear guardrails. Revenue dipped, then rose again, steadier this time, less volatile. We survived.

In the midst of all that, Tennessee pulled me back again and again.

My mother’s recovery was slow, halting. She fought rehab with a stubbornness that made her doctors sigh and me secretly proud.

“I don’t need a walker,” she protested one afternoon as I walked beside her down the hospital corridor.

“You don’t need another heart attack either,” I said.

She glared, then grudgingly accepted the metal frame again. The click of its legs on the floor echoed the rhythm of sewing machine feet in my memory.

At night, after the nurses changed her IV lines and the machines settled into their sleepy beeping, we talked. Not always about the big things. Sometimes about recipes. About Mrs. Patterson’s grandson, who’d finally gone to college. About the new pastor at church.

But eventually, inevitably, the past crept in.

“Richard told me he apologized,” she said one evening, eyes on the window where the sunset painted the parking lot orange. “For that Christmas.”

I let out a slow breath. “He said… something like an apology,” I replied.

“He told me what he said to you that night,” she murmured. “I didn’t know, not really. I was in the kitchen. I heard laughter. I thought—” Her voice cracked, and she swallowed. “I thought it was a joke.”

“It wasn’t,” I said.

“I know that now.” Her hand, veined and thin, gripped the blanket. “I should have asked. I should have stopped the party. Made him apologize right then, in front of everyone.”

“You didn’t,” I said. “You looked at your hands and pretended nothing was wrong.”

She flinched as if I’d slapped her.

“I know,” she whispered. “I have replayed that night more than you will ever understand.” Tears slid silently down her cheeks. “My mother never stood up for me. Not once. I told myself that was why I couldn’t stand up to him. Habit. Fear. Call it what you want. It was still… cowardice.”

The word hung in the room like smoke.

I’d waited a lifetime to hear her name it. When it came, it didn’t feel as satisfying as I’d imagined. It just felt sad.

“You were scared,” I said quietly.

She shook her head. “I was tired,” she replied. “Scared, yes. But more than that, I was… tired of fighting. Your father leaving, the bills, the shop, the nights I lay awake wondering if we’d eat next week. When Richard came along, I thought—” She laughed bitterly. “I thought I could finally rest. Let someone else drive. So I swallowed his comments, his temper, his pride. I told myself it was the price of not being alone.”

“And the price,” I said slowly, “was me.”

She closed her eyes. “Yes,” she whispered. “It was you. And I am so sorry, baby. I don’t expect you to forgive me. I just… needed you to know I see it now.”

I reached for her hand, my throat tight.

“Forgiveness isn’t a light switch,” I said. “It’s… a dimmer. Some days I can turn it up. Some days I can’t.”

She opened her eyes, wet and hopeful. “Is today one of the days you can?”

I thought of the years of silence, of my own therapy sessions, of the notes she’d sent after the acquisition, clumsy and earnest. I thought of her heart, mended and fragile.

Today, something in me softened.

“Yeah,” I said. “Today, I think it is.”

She rested her head back against the pillow, eyes closing again. Relief reshaped her features.

“Good,” she murmured. “Because if I had to stand before God still carrying that, I’d never hear the end of it.”

I laughed through my tears. “You think God’s that petty?” I asked.

“I think God’s a mother,” she said. “We don’t forget much.”

She got better, slowly. Went home. Let the walker go. Let us hire one of the foundation’s grantees—a shy, brilliant girl named Tasha from rural Kentucky—to help in the shop. Tasha was the one who convinced her to start selling her designs online, to ship handmade quilts to people in cities Susan had only seen on TV.

“Do you know how many orders we’ve gotten from Seattle?” my mother marveled on a call one day. “I think your friends are buying up my inventory.”

“I plead the fifth,” I said, leaning back in my office chair, watching my team through the glass wall. One of our junior engineers waved at me; I waved back.

In the middle of all this fragile newness, another blow landed.

Richard was diagnosed with prostate cancer two years after my mother’s heart attack.

He told me himself, surprisingly. Called my cell while I was in an Uber between meetings.

“I don’t want you hearing it from your mother,” he said. “She’ll make it sound like I’ve flatlined already.”

“Have you?” I asked, trying to make my voice light.

He snorted. “Not yet. But it’s… not nothing. They say it’s treatable. Radiation. Hormone therapy. All that fun stuff.”

“How are you?” I asked, and I meant it.

“I’m…” He hesitated. “More scared than I thought I’d be. Less invincible than I’ve always acted. Turns out mortality is not just for other people.”

He laughed, a brittle sound.

“I’ll come down,” I said. “For the first round of treatment. If you want.”

Silence crackled on the line. When he spoke again, his voice was softer than I’d ever heard it.

“I’d like that,” he said.

Sitting in the hospital waiting room months later, watching him shuffle back from radiation with a blanket around his shoulders, I felt an odd mixture of grief and clarity. This was the man who’d humiliated me. This was also the man my mother loved, the man who now grimaced through pain and still cracked jokes to make the nurses smile.

People do not come in simple categories. They arrive in layers.

During one long afternoon, he dozed in the chair beside me, the TV on mute in the corner. News crawls scrolled across the bottom of the screen: updates on regulations, some of which my public testimony had helped shape; headlines about tech layoffs we’d narrowly avoided by diversifying early.

He opened his eyes suddenly and turned to me.

“Do you ever regret it?” he asked.

“Regret what?” I replied.

“Making me greet you,” he said. “At the office. Making it… formal.”

I thought of all those mornings, of his tight jaw, of staffers watching the exchange like a weather report.

“No,” I said honestly. “Do you?”

He considered.

“At first, I thought it was petty,” he admitted. “Humiliating. I told myself you were just a kid on a power trip.”

“I wasn’t a kid,” I said.

“I know,” he said quickly. “I know. That’s what I’m saying. I refused to see you as anything but the girl carrying plates. Making me say ‘Ms. Mitchell’ every morning…” He shook his head. “It made me feel small.”

“Good,” I said reflexively, then winced.

He chuckled weakly. “Yeah. Good, I suppose. I deserved to feel small. I’d spent my life making other people feel that way.” He shifted in his seat, wincing as the movement pulled at tender places. “But somewhere along the line, it became… normal. Less of a punishment and more of a reminder. Of the fact that I worked in a company you saved. That I was speaking to a person whose name the sign on the building actually matched.”

He gazed at me steadily. “I don’t think I ever told you I got to be proud of you,” he said. “Not in any way that counted.”

I swallowed hard. “You told plenty of reporters you ‘worked closely’ with me,” I said. “That counts for something.”

He rolled his eyes. “I’m serious,” he said. “Watching you change that company… change me, at least a little… It’s the one part of my legacy that doesn’t make me cringe.”

The confession sat there, raw in the antiseptic light.

“Thank you,” I said quietly.

We didn’t hug. We didn’t have some cinematic reconciliation. But we sat side by side, two flawed people bound by shared history and an aging woman whose laughter we both loved, and let the old script loosen its grip.

When he finally retired from the company a year later, after his cancer went into remission, he stopped by my office on his last day. The staff gathered for cake and awkward speeches. He thanked everyone, made one last joke about expense reports, shook hands.

Then he turned to me, in front of everyone.

“Sarah,” he said. “Working for you has been the most humbling experience of my career. And the most important.”

There was a ripple of surprised murmurs. He gave a little bow—half mockery, half sincerity—and added, “Thank you for not firing me when you had every right to.”

Laughter eased the moment. I responded with a few carefully chosen words about continuity and growth and the complicated blessing of long histories. But inside, the girl who’d once wanted him to choke on his smirk sat down quietly and let the woman at the podium speak.

After the party, as he left, he paused in my doorway.

“Goodbye, Ms. Mitchell,” he said.

“Goodbye, Richard,” I replied.

For the first time, the greeting felt less like a power play and more like a nod between equals.

Part Five

I was forty-five when I finally sold my majority stake in the company.

It wasn’t a dramatic exit. No splashy IPO, no nervous ringing of bells at a stock exchange. We’d had our growth spurts and our scares. We’d weathered the scandal, the ethics overhaul, the shifting winds of regulation. I’d watched younger founders spin themselves to exhaustion chasing valuations; I no longer needed that kind of adrenaline.

Instead, we negotiated a quiet sale to a consortium of firms that had proved, over years, they understood why our ethical constraints were non-negotiable. I kept a board seat. Mark became CTO. Lisa, after much arm-twisting, agreed to step into the CEO role.

“You realize this means I get to make you come in and say ‘Good morning, Ms. Morgan’ now, right?” she joked as we signed the final documents.

“In your dreams,” I said. “You’ll be lucky if I’m awake before nine.”

The sale freed me in a way I hadn’t expected. Time stretched out, unfamiliar and full. I poured most of the proceeds into the Mitchell Foundation, turning what had been a small, scrappy operation into something with real backbone: staff, campuses, online courses, microgrants.

We opened our first physical campus in Seattle—a glass-and-brick building overlooking the water. In the lobby, under high ceilings and warm lights, we placed my mother’s old Singer sewing machine on a pedestal. People touched the metal casing reverently, not knowing the nights it had whirred to keep my childhood afloat.

A plaque beneath it read:

Out of this machine, a girl learned that work could be both survival and art. This foundation exists so no one is ever told their labor makes them less.

My mother cried when she saw it.

“This is too much,” she said, dabbing at her eyes with a tissue. “It’s just a machine.”

“It’s not,” I said. “It’s a symbol.”

She snorted. “You and your symbols,” she said. “You always did take words too seriously.”

“Wonder where I got that from,” I replied.

Richard came to the campus opening too. He walked slowly, leaning on a cane, hair more silver than gray now. A decade of illness and age had softened him around the edges. Jennifer was with him, surprisingly, her arm linked through his.

Jennifer and I had found our way back to something like civility over the years. Therapy had helped both of us. So had time and shared worry over our parents’ health. She’d married, divorced, started her own small marketing boutique that consciously refused to work with clients who peddled shame. People evolve in the strangest ways.

“Nice place,” she said, looking around the lobby. “Very… not Tennessee.”

“Wait until you see the workshop rooms,” I said. “We’re teaching high-schoolers how to read term sheets and spot predatory loans in the small print.”

“Tearing up the old playbook, huh?” she said.

“That’s the plan.”

During the ceremony, one of our newest grantees spoke: a young nonbinary founder from a tiny town in West Virginia, building a platform to help gig workers organize for fair pay. Their hands shook as they held the mic.

“I didn’t think people like me got to stand in rooms like this,” they said. “I thought we were supposed to say thank you for whatever scraps we were given and stay quiet.”

I felt that sentence in my bones.

After the speeches, as people mingled and I moved through the crowd with a practiced smile, I caught sight of Richard standing alone near the sewing machine. He was reading the plaque, lips moving slightly as he traced the words.

I walked over.

“You never told me you were putting this here,” he said, gesturing at the pedestal.

“I wanted to surprise Mom,” I said. “And you, I guess.”

He nodded slowly. “It’s good,” he said. “It’s… right.”

We stood there in silence, two people staring at a machine that had outlived more than one marriage, more than one job, more than one version of me.

“Do you ever miss it?” he asked suddenly.

“Miss what?”

“The company. The… chase.” He smiled faintly. “The mornings where you made me say ‘Good morning, Ms. Mitchell’ with half the office watching.”

I laughed. “Every time I wake up without twenty unread crisis emails, I miss it less,” I said. “But yeah. Sometimes I miss the puzzle of it. The feeling of… fixing something broken.”

I glanced at him. “What about you? Do you miss being the man with his name on the door?”

He considered.

“Sometimes,” he admitted. “Then I remember how much weight that name had to carry. And how easy it was to hide inside it.” He looked at me. “These days, I mostly try to be someone my grandkids don’t have to heal from.”

“You’re a grandfather now,” I said. “That still freaks me out.”

“Join the club,” he said wryly. “You know what my eldest asked me the other day? She said, ‘Grandpa, were you always nice?’”

“And what did you say?” I asked.

“I told her no,” he said plainly. “I told her I used to be very good at being mean. At making people feel small so I could feel big. And that I’d spent the last decade learning how to do the opposite.” He glanced at me. “She asked me who taught me. I told her a very stubborn woman named Sarah Mitchell.”

Heat flushed my cheeks. “You could have just said ‘life,’” I said lightly.

“I could have,” he agreed. “But it wouldn’t have been true.”

At the end of the evening, when most of the guests had drifted out and the staff was stacking chairs, he approached me one last time.

“I’ve been thinking about that night,” he said without preamble.

“Which one?” I asked, though I knew.

“The party. The plates. The maid comment.” Even now, the word sounded sour in his mouth.

“We’ve… covered that ground,” I said gently.

“We have,” he said. “But you once told me you built your whole life off that night. I wanted you to know that I’ve tried to build the rest of mine off the morning I first had to call you Ms. Mitchell.”

I frowned, confused.

“What do you mean?”

He smiled sadly.

“That was the first time I realized my words had come back to haunt me,” he said. “Not as a ghost, but as a witness. Every time I said ‘Good morning, Ms. Mitchell,’ I had to look at the woman I’d tried to shrink and see how badly I’d misjudged her. It was like… penance with coffee.” His eyes gleamed. “And if I could change one thing, it wouldn’t be that you made me greet you. It would be that you had to ask.”

I looked at him for a long moment.

“Richard,” I said quietly, “when you first made me say ‘good morning’ to you in our old house—because that’s what it was, not words but expectation—I learned that greetings can be weapons. You taught me that. I weaponized it back. Maybe that wasn’t noble. But it got your attention.”

He nodded. “It did,” he said. “And then, slowly, it became… habit. Respect, even. I guess that’s how change feels. Awkward, then normal.”

We stood there, two people bound by a shared sentence that had echoed through years in different forms.

“Good night, Richard,” I said.

He smiled. “Good night, Ms. Mitchell,” he replied.

This time, the words felt clean.

Years slid by.

I taught more. Traveled less. Wrote a book I never thought I’d write, about power and work and the strange, crooked roads that lead us to the seats we occupy. I taught a seminar at my old university once a year, standing in front of students who reminded me painfully of myself. Some of them had stepfathers. Some had bosses who called them names in front of colleagues. Some had their own embers tucked into pockets, waiting.

“If someone calls you small,” I told them, “you don’t have to prove them wrong to their face. You can prove them wrong by building a life where their words don’t decide your size.”

One semester, after a lecture, a lanky young man with nervous hands hovered at the edge of the stage.

“My mom remarried when I was ten,” he said when I walked over. “My stepfather tells me I should be grateful he puts a roof over my head. He says my grades don’t matter, that I’ll end up ‘changing tires like the rest of us.’”

He looked at me, eyes shining with a familiar mix of anger and shame.

“I got a scholarship,” he said. “I’m here. But every time I go home, I feel… small again. Like I’m pretending to be someone I’m not allowed to be.”

I thought of Tennessee, of silverware clinking, of my mother’s bowed head.

“I know that feeling,” I said. “Better than I’d like.”

“What did you do?” he asked.

I smiled.

“I built something he couldn’t ignore,” I said. “Not to spite him. Not in the long run. For myself. For the people coming after me. And I made him greet me every morning in the one place he’d always assumed he’d outrank me.”

He blinked. “You… made him say hi?”

“It wasn’t about the ‘hi,’” I said. “It was about making him say my name with respect. About reminding both of us, daily, who I had become.”

I rested a hand on the podium.

“You may never get that from your stepfather,” I continued. “He may never see you clearly. But you can still build a life where his version of you doesn’t hold the microphone.”

He nodded slowly, jaw setting.

“I want that,” he said.

“Good,” I replied. “Start small. Start with the work in front of you. Let your anger be fuel, not fire that burns you from the inside.”

He smiled a little. “You sound like my therapist,” he said.

“Pay her extra,” I said. “She’s doing good work.”

When the young man left, I sat alone in the empty lecture hall for a few minutes, listening to the echo of my own footsteps as I gathered my notes. The room smelled of dust and old ambition.

On my phone, a text lit up from my mother: Richard’s at the shop again, flirting with death by sugar cookies. Call when you’re done pretending to be famous.

Another from Lisa: Board meeting went great. They approved the new apprenticeship program. You’d have been proud. Also, I figure out a way to make interns say “Good morning, Ms. Morgan” without HR getting mad. Kidding. Mostly.

I laughed, the sound bouncing off the seats.

Walking out into the evening light, I felt that familiar ember in my chest—not the sharp, furious coal it had once been, but a steady warmth. A pilot light that no longer needed an enemy to stay lit.

My life had become a series of greetings: to clients, to students, to founders walking for the first time into rooms they’d been told they didn’t belong in. To my mother, who called me by my full name when she was proud. To Richard, whose “Ms. Mitchell” had gone from bitter to bemused to genuinely fond over the years.

For a long time, I thought the story started and ended with a single sentence at a Christmas party and another at an office door. But standing there outside the university, backpack slung over one shoulder like a student again, I realized the truth was bigger.

The story wasn’t just that my stepfather once called me a maid in my own home.

The story was that I refused to stay a character in his version of my life. I rewrote the script, line by line, until the woman he dragged toward the kitchen was the same woman he had to greet, every morning, in a lobby where my name was on the wall.

And then, crucially, I kept writing. Beyond him. Beyond us.

I built structures where no one’s dignity hinged on someone else’s mood. I helped people I’d never meet step out of roles they’d been assigned—maid, assistant, background noise—and into their own names.

On some mornings, at the foundation’s Seattle campus, I arrive early. The sun creeps over the water, turning the windows gold. Staff trickle in, calling out to each other, carrying coffee and laptops and stories. They greet me in a dozen different ways.

“Morning, Sarah!”

“Hey, boss!”

“You’re in early. Who are you and what have you done with our founder?”

No one calls me “Ms. Mitchell” unless they’re teasing. I don’t need the formality anymore to feel the shift in power. The respect is there in other forms: in the way people argue with me without fear, in the way junior staffers suggest changes and know they’ll be heard, in the way no one ever tells the intern to “get back to the kitchen.”

Sometimes, when the building is quiet, I walk over to the Singer in the lobby and rest my fingers on the worn metal. The plaque catches the light. The story beneath it continues in the footsteps that cross this floor every day.

I think of every girl and boy and nonbinary kid in every small town who is called a maid, a nobody, a burden. I imagine them, years from now, walking into offices they built themselves. I hope they’ll remember that respect doesn’t start in someone else’s mouth. It starts in the way you greet yourself when you look in the mirror.

Good morning, I tell my reflection now, not Ms. Mitchell, not maid, just Sarah.

And for the first time in a long, long time, the greeting feels simple.

Not a battle cry. Not a ledger. Just an acknowledgment that I am here, in a life I refused to shrink for anyone.

A life I built, stitch by stubborn stitch, exactly my size.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Sister Hired Private Investigators to Prove I Was Lying And Accidentally Exposed Her Own Fraud…

My Sister Hired Private Investigators to Prove I Was Lying And Accidentally Exposed Her Own Fraud… My sister hired private…

AT MY SISTER’S CELEBRATIONPARTY, MY OWN BROTHER-IN-LAW POINTED AT ME AND SPAT: “TRASH. GO SERVE!

At My Sister’s Celebration Party, My Own Brother-in-Law Pointed At Me And Spat: “Trash. Go Serve!” My Parents Just Watched….

Brother Crashed My Car And Left Me Injured—Parents Begged Me To Lie. The EMT Had Other Plans…

Brother Crashed My Car And Left Me Injured—Parents Begged Me To Lie. The EMT Had Other Plans… Part 1…

My Sister Slapped My Daughter In Front Of Everyone For Being “Too Messy” My Parents Laughed…

My Sister Slapped My Daughter In Front Of Everyone For Being “Too Messy” My Parents Laughed… Part 1 My…

My Whole Family Skipped My Wedding — And Pretended They “Never Got The Invite.”

My Whole Family Skipped My Wedding — And Pretended They “Never Got The Invite.” Part 1 I stopped telling…

My Dad Threw me Out Over a Secret, 15 years later, They Came to My Door and…

My Dad Threw Me Out Over a Secret, 15 Years Later, They Came to My Door and… Part 1:…

End of content

No more pages to load