My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing

Part One

Stop. Stop, stop—you’re hurting me.

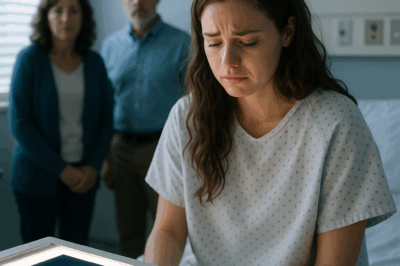

The words came out raw, thin as the thread of a stitch pulling under pressure. Brad’s fingers tightened in my hair and the world narrowed to that single, burning point. The room tilted and I felt my scalp tear like paper as he dragged me across the bedroom floor. “Get up, you lazy piece of trash,” he barked, voice booming. Behind him my mother laughed, the small, cruel camera-light of her phone making her face look flatter, smugger.

“Maybe next time you’ll think twice before disrespecting us,” she said, still filming. “This is hilarious.”

There are three small moments seared into me from that morning that became a kind of map for the rest of my life. The first: the precise hot flare of pain when his hand twisted a fistful of my hair. The second: my mother’s laughter, bright and light and delighted, echoing off white plaster. The third: the cold, steady arrival of a decision inside me that yearned to be freedom.

I was seventeen that week, two semesters away from graduating high school, one frantic scholarship essay from the exit door I’d been circling since I was a kid. My father had died when I was twelve. The accident left a raw place in our lives that married on, as such heartbreaks do, into lack and trying. For a while my mother kept the house like a frightened animal; she took two jobs, waited tables and folded linens, swallowed pride and exhaustion alike. Money was scraped thin, but we were together. I thought our small miseries were the kind that teachers could give us pep talks about and friends could taste to make light. I thought—childish, hopeful—that things might get better.

Then my mother met Brad.

He was a different kind of rescue: a man who owned auto shops, whose laugh was confident enough to be contagious, whose drink offered expensive reassurance. He bought my mother dinners and chose a tight, glittering dress for the courthouse wedding six months later. He promised security, a big house, someone to take the strain off. My mother, exhausted and dazzled, said yes. I wanted to be happy for her; I wanted to be grateful. Instead I landed in a house that felt like a prison.

From the very first day there were rules. Wake at five. Clean before school. No friends over without permission. No phone past eight, grades must be flawless. Brad called it “respect.” He said it with the kind of force that made the word feel like a weapon. “In my house everyone contributes,” he declared, as if ownership of space justified ownership of people.

The first bruise appeared four months after the wedding. I had simply forgotten to take out the trash—late-night AP homework had become my life—and he grabbed my arm in the kitchen hard enough to leave a crescent blossom of purple. When I showed my mother, she looked at it like a minor weather event and said, “Don’t be dramatic.” She did not file a report. She did not panic. She did not, in the only way that mattered, stop him.

The abuse escalated slowly, carefully—measured so that it could be explained away. Shoves tucked behind the façade of a parental reprimand; slaps hidden under the excuse of discipline; words sharpened into humiliation. He read my diary at the dinner table, laughed at the shape of my handwriting. He threw my drawings into the garbage as if they were trash. He deleted my social media accounts, then blamed me for not keeping connections. When he called me “chunky” at a meal, my mother would chuckle and say, “Maybe skip dessert tonight.” A shrug, a dismissal. A complicity as simple as a look that shifted allegiance.

You learn to live in the narrow spaces—at school, at the library, in the art room late after practice—places where light makes sense and bodies can breathe. My art teacher, Ms. Chen, saw me. She had a quiet way of anchoring people; once, she left a sketchbook on my desk, a small encouragement like a lifeline. My best friend Emma tried to help—meal offers and whispered rescue plans—but Brad read friendship as disobedience. He forbid me from seeing Emma. He forbade me from accepting calls from my aunt Julie—my father’s sister—who had been my childhood ally. He intercepted letters, hid phone numbers, built an administrative prison around me.

The house had rules, yes—but the rules never read my bones. The consequences were standardized, surgical. If I were late to the kitchen, he would humiliate the entire morning by assigning extra chores. If I wore a shirt he disliked, he would stand in the doorway and call me “showy.” He calculated shame like an accountant. My mother, who had once taught me how to braid her hair, learned instead how to laugh at my mishaps and step over me on the floor. Her phone captured my pain for strangers in Facebook groups that praised “strict parenting.”

That morning—when he yanked me by the hair and she laughed—was the culmination of months, years of little choices that became something monstrous. They filmed the incident and posted it to a private group celebrated for cruel parenting tactics. The reaction of the group surprised no one in the room; the video collected likes and comments that encouraged harsher discipline. “Brings a tear to my eye,” someone wrote, as if creation only counted when it included cruelty.

But the brutality did one useful thing: it made evidence. When Ms. Chen found me that day, tangled and bruised, she did not avert her eyes. She pressed her hands to my shoulder and said, in that precise steady way of conscientious adults, “You don’t have to do this alone.” She took me to the nurse, who filled forms and circled injuries on a sheet. She ushered me to the counselor.

It takes a certain kind of courage to list the pattern of violence out loud. It takes a different kind of bravery to hand over the one thing abusers treasure: control. I told them dates, details; the diary that had been read aloud at dinner; the messages that threatened punishment if I spoke; the video my mother had filmed like evidence of my delinquency. My voice shook, but not as much as the relief that followed.

Once the school filed reports, things moved with an efficiency that felt unfamiliar. People who had been gathering details for a living—lawyers, detectives—arrived at a different cadence than the household. Child Protective Services placed me in a foster plan. My aunt Julie, who had never stopped trying to reach me, came to the school and brought a hug that smelled like cinnamon and reframing. “You’re safe now,” she said, and the words fell into me like water.

They arrested them that night. It happened while I sat in Julie’s small living room and drank hot chocolate, the warmth of it a tribute to a world that had human hands. The detective showed me screenshots of the Facebook group: comments reveling in pain, strangers urging harsher punishments. It made my skin crawl. The prosecutor—grim and professional—said the recorded video was the damning piece: premeditation, conspiracy to abuse, endangerment. When the police took Brad and Patricia away in cuffs, the neighborhood watched with the curious hush that follows the unexpected disappearance of an ordinary monster.

The legal process that followed was a raw slice of public exposure. My mother tried to play the manipulative card: “Brad was a strong personality. He manipulated me.” The footage on her phone had no ambiguity, however. Her laughter could not be argued into kindness. The jury saw that. They heard the unfunny jokes. The prosecutor played the school nurse’s statements, the counselor’s notes, the records of bruising, the testimony from classmates who had seen Brad yell. People who had once believed in private indignities now saw how wide the harm reached. Brad was sentenced. Patricia was sentenced. Their sentences were a measure of what they’d done; they did not automatically provide comfort for what I had lost.

After the trial, life was a complicated patchwork. I moved in with Aunt Julie, who became my legal guardian for the final months of high school. She sat with me during therapy sessions, pinned my resume for college scholarships to a cork board like a talisman. The healing was gradual, allergic, interrupted by nightmares and reacquaintance with normal food. I gained weight back; my body remembered that food could be kindness, not control. I learned to sleep without panic attacks puncturing the night.

The court, the social workers, the hospital visits—they were all signs that I was not invisible. People came forward in ways that felt like stitches: grandparents who had been cut off by Brad’s lies finally embraced me, guilt saturated by relief. The world that had been my home had become a cautionary tale: Brad’s empire of garages crumbled as employees testified to his temper and his control. Patricia’s social circle fractured. The cover-ups unraveled like cheap thread.

Still, the aftershocks arrived in unexpected guises. There were relatives who told me to forgive, to understand, to bring the family together because “blood is thicker than water.” There were the nights when guilt would trail me like a shadow: the thought that the police had taken my mother to jail because of me. But the legal work had nothing to do with me personally; it had to do with the choice they had made to abuse and to celebrate that abuse publicly.

When I look back at that time, the most important thing I remember is not the abuse itself but what followed—what I did with the chance to leave. It would have been so easy to let rage calcify into bitterness. Instead, I chose to tell the truth to the people who could help, to accept the messy process of healing and to walk away from a family that had not kept me safe. I embraced the idea that a family can be chosen.

Aunt Julie stitched my life in small, steady patterns. She helped me gather college forms, she drove me to therapy, she opened the door to a world where people fixed things because it was right, not because it made for good social media. Under her roof I began to understand that abuse is not a private manner—it’s a public violation—and that survivors can reclaim themselves.

The cameras that had filmed me as an object of ridicule later filmed me as a witness. They showed my voice, my testimony in court. My mother’s laughter—the sound I once wanted to erase from the world—became evidence for my safety. The same devices that had been twisted into tools of humiliation were, ironically, what allowed the truth to surface. The irony was not poetic; it was practical.

After graduation, I took full advantage of scholarship offers. My artwork—sometimes abstract, sometimes raw—became a language I used to explain what words could not. One of my pieces, a portfolio called Surviving, put the map of these years onto paper. It was dark at first, then slowly luminous: charcoal forms breaking into line, an arm emerging from shadow toward light. The admissions committee at an art school found it honest and brave in a way that felt like being understood by strangers.

I would learn, over the next several years, that healing is not a straight line. You never completely unlearn flinches or the heat that flashes when a hand moves too quickly. But you learn that those reactions are not the whole of you. You learn also that the people who stood up for you—your aunt, your art teacher, a few dedicated counselors—can be the cores of new families formed not by DNA but by choice. That idea steadied me as I rebuilt.

Part Two

The years after the trial felt like walking through a city you had once loved and now scanned for danger at every corner. I graduated, I left my small hometown, I made a home that was mine: small, with sun on the kitchen counter and an over-eager spider plant in the window. I painted. I sat in classes. I slept when I wanted. I ate when I was hungry. I dated a man who learned my triggers before he learned my favorite color. His name was Marcus, and he was patient as spring rain.

Healing, for me, involved a hard apprenticeship at normalcy. The therapist’s office with Dr. Williams became a place where I translated survival instincts into healthy habits. “Your body kept you alive by going into survival,” she told me in the first months. “Now we need to teach it that you are allowed to be safe.” That teaching involved confronting things that felt small but were actually enormous: eating when I wanted, refusing to apologize for existing, sleeping on the side of the bed farthest from the door. We practiced breathing exercises in the morning, made a plan for nightmares, rewired the little frays that terror had left in my wiring.

I found work as a graphic designer. My art reached people; my journey became material rather than purely private trauma. I started volunteering for organizations that helped survivors tell their stories in ways that were empowering rather than voyeuristic. I spoke at a conference once, nerves alive in my throat like a hundred bees. But when I finished the talk and teens came forward to tell me their own truths, the words came back to me as a kind of payback: this was how you give the gift you never received—by standing up in public and making a room safer for others.

Brad and my mother were released on parole at different times years later. Brad’s release triggered a protective mechanism in me—I filed for and obtained long-term restraining orders. The state made the restraining order comprehensive; any contact would result in immediate arrest. Patricia’s release was quieter. She landed in a halfway house out of state. Sometimes the news feeds held fragments—her name appeared in a social services docket, as if the machinery of consequence never forgot.

When they were out, my life had already moved. I married Marcus. Aunt Julie walked me down the aisle. In the warm afternoon light of the garden where we married, I felt a kind of completion that had nothing to do with vindication and everything to do with choice: choosing a partner who knew and sheltered my fragility, choosing to create a domestic life differently. Julie took a photo as I hugged Marcus and I kept the image near the cork board where my scholarship letters had once lived.

That’s not to say all wounds healed. Some scars rewrote themselves into stories I carried to the kitchen table, to the gallery, to the conference. I still flinched. I still woke some nights and sat bolt upright, the body remembering the rules like a language I had once spoken fluently. Sleep, after years of being rationed and scheduled by someone else, took practice.

Yet there was meaning in the way the legal system had recognized my claim. They had not arrested my mother and stepfather only because of a moment of rage; the indictment had recognized a pattern of calculated behavior and the public cheering that had amplified that cruelty. The prosecution had pulled at threads of community—those private Facebook groups, the network of cheering disciplinarians—and exposed an ugly filter underneath. When the judge sadly read the sentence, “conspiracy to abuse,” perhaps no one in the courtroom felt triumph. There was grief in the room for the wasted choices, for the multiplicity of harms beyond me.

My life acquired a public dimension I had never asked for. I gave interviews, agreed to be a face for organizations, maintained boundaries about what details I would share and which I would guard. For every person who wrote me a private message to say “thank you,” there were others who assumed my life must be folded into constant heroics. The truth was more banal and human: I had learned to live. I had learned to fight bureaucracy and to accept help. I had learned to trust again.

The legal closure did not erase the fact that the man who had raped my domestic life had once stood in the doorway promising kindness. People said things like “how could she have been fooled?” as if the script of abuse were a simple story. But the pattern of coercion is subtle and patient: it lives in the rearrangement of money, the cutting off of support, the insistence that people outside the family be dismissed as meddlesome. It’s the slow freezing of a person’s world until the only voice left is the abuser’s.

That, perhaps, is why I decided to take some of my hours and give them away. I began, with a small stipend from a gallery commission, a program to help teens in similar circumstances—an art residency that combined therapy with technical training. We called the program Sketching Safety. There is something about creating with one’s hands that teaches a body how to trust its touch again. I taught them the basic gestures, the vocabulary of composition. We did not demand art be confessional; we asked only that they explore. Some did produce images that were shadowed with pain. Others found solace in absurdity. All of them learned that it was okay to be seen without being judged.

It changed me, too. When a teenager walked up to me at a community center and said, “I saw your talk and it made me not feel so crazy,” I remembered the feeling of being nineteen and alone with bruises. I used that memory not to feel righteous but to be useful. It’s a small philosophy but a durable one: harm can be countered by presence. If we show up for the young people who are drowning, fewer of them will be left to fight the undertow alone.

There were personal reckonings that came later. My mother wrote letters from her halfway house. At first, they were mostly apology without action—cheap emotional currency. In the second year, she started mailing me articles on parenting and therapy workbooks with clumsy notes. She wrote about the panic she felt the day she realized she had filmed her child being harmed. She wrote about how the cheers on the Facebook group quieted into a thin, shameful background noise. She wrote, finally, about regret.

Forgiveness is not a simple thing. It cannot be commanded or purchased. It requires honest labor—work in the open to make reparations, to show up again and again, and to accept consequences. My mother engaged in some of that work slowly. She began to hold a job that paid little and taught her the value of a steady schedule. She started group therapy and would sometimes mention details about what she had learned, the small rituals she was attempting to unlearn. She sent gifts—useful things, not expensive ones. She asked about my life in a way that was measured rather than demanding.

We met in the middle, sometimes like two strangers waiting at the same train. I did not invite her back into my home right away. I did, however, sit with her in a public place a handful of times. I listened more than I spoke. I set firm boundaries: no references to what she had filmed, no excuses, no gaslighting. She honored those terms. The threads between us were frayed but not irreparably severed; they could be rewoven, slowly, with the kind of patience that admits failure without denying effort.

Daphne’s release was later and complicated. Prison is a place that can be clarifying, but it isn’t always redemptive. She came out thin and quiet, the bright theatricality drained from her face. The children—my nieces and nephews—had been cared for by fathers, grandparents, and a neighborhood that had once turned away. Life after prison is a focused negotiation of trust. She attended counseling and parenting classes as a condition of parole and, slowly, the court records and restitution regimes guided some parts of her life into repair. Whether she could regain a social footing beyond that was less a matter of justice and more of practical rebuilding: steady work, financial accountability, and an insistence from the family that anything else must be earned.

People asked me, early on, whether I felt satisfaction at seeing the offenses judged. My answer was always complicated: there was relief that law had recognized harm and an intense, sorrowful pity that a life could be so misdirected. The public punishment did not come with a tidy redemption. Punishment rarely carries answers. It simply marks a line and asks society to step over it.

When I married, I invited my biological grandparents and Aunt Julie, and a small circle of friends who had been witness to my rebuilding. I did not invite anyone who had been part of the abuse. There were choices there, of course, that some people said were cold. But protection is also an act of love. A marriage is not only about celebration; it is also a vow to create a safe environment for the future I wanted.

Sometimes I’m asked if the video my mother made was what saved me. In a literal legal sense, yes—the footage was decisive; she had filmed her own role in the harm. In a moral sense, it is more complicated. The recording legitimized evidence, turned private cruelty into public knowledge. But the rescue came from adults who saw the truth and acted: Ms. Chen, the school nurse, the counselor, Aunt Julie, the detective—people who recognized that children’s suffering is not a family secret to be tolerated. The infrastructure of care moved with the urgency that the law allows when a child’s safety is in question.

There are days when I dream of being able to sit at my mother’s kitchen table and have a normal conversation about nothing. Those days are less common than I once hoped. Mostly I have adjusted to the reality that family is a choice. I have chosen people who show up consistently. I have chosen to provide places where children can be heard. It’s not heroic. It’s simply right.

In the work that followed, I met other survivors. I heard stories that were similar and others that were wildly different, but each held the same fragile core: someone was supposed to protect them and did not. Hearing dozens of such stories taught me two things. First: isolation is the abuser’s greatest weapon. Cut off help and the person becomes a house of sand. Second: the smallest interventions can be the most transformative. A teacher who notices and acts, a neighbor who refuses to look away, a social worker who pushes the case forward—these are the repairs.

One afternoon, at a gallery showing of Surviving, a young woman came up to me, trembling, and said, “I think my stepdad is like yours.” She had a piece of paper with a note about a local shelter. I held her hand and sat with her, and we called a hotline in the next hour. She told me later that the call was the first step of a chain that led to safety. Those connections kept me going—evidence, finally, that my ordeal had gained some utility beyond my own survival.

Years passed. Brad moved into the margins of the news and then out of it. Patricia remained distant, her life smaller and stripped of the codes of authority she once wore. They did not holler at me from the street or bomb my mailbox. The court’s restraining orders worked as fences. I do not relish their absence. I do not wish harm. I simply live my life with guards of realism and measures of care.

Sometimes I imagine the life that could have been—one without the bruise, the humiliation, the film. The image is tempting and spare: a kitchen where my mother stood protecting me, not filming. But history was written and the choices were made. The only control I have is over how I respond to the pages that came after.

The last line of this story is not grand. There were no cinematic reconciliations, no public confessions that fixed everything. My mother and I did not become carbon copies of how families are sold in holiday cards. We became, instead, two people who had weathered collapse and who were trying, haltingly, to be better in small ways.

At my daughter’s—my niece’s—college graduation, my mother sat in the audience and clapped with hands that had once been instruments of cruelty. She wore a small, earnest smile as if each clap cost her. I did not storm the stage. I stood up and hugged my niece in public, the movement natural and discreet; then I lifted my face and the eyes that found me were not the accusatory ones from years back but tired, human, and perhaps learning. That was the clearest ending I could imagine: not annihilation of the past, but a continued insistence that the present could be kinder than it had to be.

So if you see a parent filming abuse and smiling, don’t assume it’s merely strict parenting. Don’t walk away. Speak up. A single call, a single voice, can tilt the arc of a life that is sliding toward harm. And if you are the one who was harmed, know this: your story does not end in the room where you were violated. It extends outward into rooms you choose, into galleries and conferences, into listening ears and hands that will guide you through paperwork and therapy and sleepless nights. It ends not with punishment, but with the slow, steady rebuilding of a life you can wake to without fear.

I still have nightmares sometimes. I still flinch. Some mornings I wake and remind my body: this is your house, now. This is your bed. This is your life. The rest I stack up in small victories—an exhibition, a speech, a friend who understands silence. The final truth I carry is not an annihilating vengeance but a quieter certainty: I survived, and from that survival I chose to build a life that would protect others from drowning.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Parents Said My Headaches Were ‘Attention Seeking ‘ The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden. CH2

Parents Said My Headaches Were “Attention Seeking.” The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden PART 1 The migraines started…

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything. CH2

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything Part One The slap arrived with…

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career. CH2

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career Part One They…

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour… CH2

I had just bought the country house when my daughter called: “Mom, get ready! In an hour, I’ll be there…

MY BROTHER BROKE MY RIBS. MOM WHISPERED, “STAY QUIET -HE HAS A FUTURE.” BUT MY DOCTOR DIDN’T… CH2

My brother broke my ribs. Mom whispered, “Stay quiet – he has a future.” But my doctor didn’t blink. She…

MY BROTHER-IN-LAW ASSAULTED ΜΕ- BLOODY FACE, DISLOCATED SHOULDER MY SISTER JUST SAID”YOU SHOULD… CH2

My brother-in-law assaulted me — bloody face, dislocated shoulder; my sister just said “You should’ve signed the mortgage.” All because…

End of content

No more pages to load