My Son’s Bride Slapped Me at the Wedding, But My Son’s Reaction Made Her Face Pale

Part I

The sound of crystal on marble can sound like a lullaby in the right room—soft, expensive music—but not when it’s a dozen champagne flutes skittering across a museum’s floor and a mother’s hand flying to her mouth too late. The quartet stopped mid-bow. A laugh stalled in someone’s throat. You can hear a silence take a breath if you’ve spent enough nights listening for the coal trucks that no longer come.

“You stupid, clumsy country woman. You ruined my dress. Do you have any idea what you’ve just destroyed?”

I dropped to my knees because that is what my hands have always done—reach, save, gather, sweep. I reached into the angry sparkle of glass as if I could unbreak it. “I’m sorry,” I managed, thin as a thread.

“Don’t touch me.”

The slap landed before the shame did. It cracked the air, turned my cheek to heat, turned the hall into a canyon. I stared at the floor I’d been trying to rescue from my mistake and felt the shape of her fingers bloom in my skin like a cruel flower.

“Victoria, what did you just do?” my son said.

I am Connie Lawrence. I am sixty-eight years old. When people ask what I did with my life, I could say waitress, housecleaner, seamstress. I could say widow. I could say mother and be finished.

Thomas, my husband, died when our boy was fourteen. Not all at once, the way men in good stories die. The mine started it—a cave-in that left his leg not quite right and his cough louder than any radio. The black lung finished him slowly, one dusty inch at a time. Doctors called it pneumoconiosis. I called it a mountain swallowing a man I loved.

By then our town in West Virginia sounded like a clock that had forgotten how to tick. The mine closed. The young left. The old stayed because the dead can spend years standing up, and staying put is easier than leaving when everywhere else is a rumor.

Bills stacked. The hospital, the pharmacy, the funeral home—all sending their names on envelopes that might as well have been tombstones. I had a boy who learned faster than hunger, whose teachers said college like it was a life preserver. “Advanced placement,” they said, and the words cost a fee. Everything cost a fee.

I wore my navy funeral dress to the principal’s office and tried to make it look like dignity instead of survival. “An extension,” I said. “I’ll pay in installments. I won’t miss.” Mr. Brennan leaned back with the look of a man who’s never been surprised by a bill. “We have rules,” he said, the way men say no without ruining their lunch. He granted me the extension at last and made me sign a paper like I’d borrowed his firstborn.

I learned years later that Liam had stood outside that office, coat in hand, hearing my voice bend but not break. He never told me he’d heard. He didn’t have to; I saw the fire it left in him glow hotter each winter.

I worked. Diner on Main—coffee that tasted like it had been brewed in a nail tin, eggs that slid like apologies, men who left change they needed more than I did. I smiled anyway. Nights I drove to the next town and cleaned the places of the people who still had “later” in their voices. I scrubbed until my hands were raw, then hid them in my apron when I walked through our door because boys shouldn’t know how much their mothers bleed. When there were hours left, I sewed for neighbors—patches, hems, buttons that refused to obey.

When Liam needed the last dollars to start community college, I told him I’d saved. I did not tell him I had sold Thomas’s stamp album and his grandfather’s watch, the one engraved Time is the only wealth that matters. I put the cash in an envelope and placed it in our boy’s palm and said his father would be proud. I put my hands in dishwater and swallowed my tears with the suds.

He made it out. He made it further than out. Years later he climbed out of a car so black it reflected the sky and smiled like he was still the boy who did algebra under the yellow kitchen light. But he was someone the papers called Founder and CEO now. He built an app to keep people like us from the grip of men who smell desperation and call it opportunity. “Fintech,” he said, and I nodded as if I understood.

“Do you remember the man who came every Friday to collect?” he asked once, voice low. I remembered the slick hair and the punctual knock and the interest that grew like mold in the damp. I remembered.

The first thing he did with his fortune was open the sky and put me in it. A private plane, then a penthouse with windows that taught me the size of the world. Floors that looked like water and chairs that looked like no one had ever dared to sit. Hands appeared to do the jobs my hands had always done. I woke at five anyway, made coffee because my muscles didn’t know about “staff,” folded laundry before a woman with a perfect mouth told me, gently, that it was her job. “Keeping my hands busy is how I breathe,” I said, and my son kissed my forehead like I was something fragile and left for work in a suit I could have financed a semester with.

Victoria came into the room like a draft under a door—felt before seen. She was tall and sharp and beautiful in the way museums are beautiful: expensive, curated, chilly. An art critic. Old money, people said, like money can age into nobility if you just keep it long enough. In rooms with other people she was charming about my story, saying rags-to-riches like a ribbon. When Liam left, she corrected the way I said museum and suggested stores with quiet lighting where dresses cost more than cars do when they’re honest. “You’d love it,” she’d say, smiling with her eyes turned off.

At a dinner with her friends, I misunderstood the forks. I picked up the wrong one and set off an orchestra of looks. The fork clanged and the room went still, and Victoria laughed, tinkling and cruel. “Oh, Connie, darling,” she said. “We’re using the Tiffany silver, not the tin forks from the diner.”

Liam chuckled with the rest because he doesn’t hear poison when it’s wrapped in lace. I heard it. I placed the fork where it belonged and placed the moment somewhere I would find later, after dishes, after guests, after the ache.

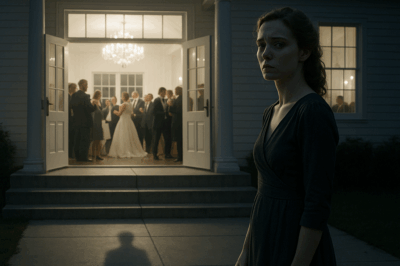

When the wedding came, I let him buy me a dress. Plain blue, the color of sunrise before the world decides what it will be. The hall was a museum pretending to be a chapel, marble floors and ceilings high enough to echo a man’s doubt. People wore money like perfume. Photographers flashed. The air tasted like wealth and canapés.

My son stood with a glass on a stage and I stood in the back where mothers stand when they don’t want to block anyone’s view. A boy—not a guest, a worker—shouldered a tray too heavy for his arms. His hands were white from the strain. I moved the way I always have. “Here, son,” I said. “Let me steady it.” Relief washed his face. I guided the weight a moment, then stepped back. My heel found the rug’s edge like a trap. I stumbled. The tray tilted. Twelve flutes became birds with broken wings.

The champagne found silk. The silk screamed.

“What the hell did you do, you stupid, clumsy backwater woman?” Victoria spat. “Do you have any idea what this dress costs? You’ve ruined my wedding.”

“I—I’m sorry,” I said, and meant it all the way to the years behind me.

Her hand flew. The sound cracked. The room held its breath, and I held my cheek and remembered every time my hands had saved something small and how this time they had failed.

“Victoria, what did you just do?” Liam’s voice came through the quiet like a knife through fabric.

She turned, panic a flicker, then chose performance. “She ruined my dress, Liam. I don’t even know how she got in here. She must be staff. Get her out.”

He didn’t look at her. He knelt beside me, lifted his jacket—tailored and perfect and irrelevant—and draped it over my shoulders like a blessing. He stood. “She is not the staff,” he said. “She is my mother.”

The room gasped the way crowds do when they realize the hero has been here the whole time and they were pointing at the wrong light. Flash. Whisper. A rustle like a field of corn in a storm.

Liam walked to the microphone. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, calm and steady, “thank you for coming. The reception is over.” He turned to Victoria, and his voice did not change. “And so is my marriage.”

Part II

News moves faster than shame and slower than justice. Someone filmed the whole thing—hands always rise when there’s a story to steal—and within minutes the slap had a name and a loop and a hashtag. Weeks later, tired morning shows would still be pretending to be surprised by the same thirty-second clip. Websites with names like gossip and words like exclusive judged it from every angle. There are a thousand ways to be wrong about a story you were never in.

Brands she had loved for their weight and names that made other women nod pulled their names away from hers. Charity boards untied their knots. Magazines that had printed her adjectives pretended they had never met her verbs. You can’t sue the internet. You can’t even ask it to be quiet.

They dug into me too, like miners who’d forgotten what treasure looks like when it isn’t shiny. They found the town. They found Thomas’s death certificate and the note from the principal who suddenly remembered that he’d always been on my side. They called me a symbol—for dignity, humility, motherhood—as if a woman can be reduced to a poster even when the poster is kind. Liam said, “I can’t stop it, Mom,” and I believed him because nothing can stop a story that makes strangers feel like they’re good for choosing the right side.

I asked him not to sue Victoria. He wanted to. A son’s fury is a hot thing, and he’s a man who likes solutions you can hold in court. “She’s already lost enough,” I said. His jaw worked. He nodded. He didn’t need a lawsuit; he had four words that had already done the work: I choose my mother.

We went north, to a house where trees are the only paparazzi. The quiet there had weight. We cooked food that had more comfort than elegance. He came home earlier. He fell asleep on me during old movies, black-and-white men saying lines that sounded better because a world had given them to us as proof that sense used to be common.

But my hands don’t know how to be idle. They itch if they aren’t holding something that needs doing. I found a soup kitchen in Brooklyn—church basement, big pots, small budget, holy hunger. I chopped onions and carrots until the kitchen smelled like home and made bread rolls that reminded my palms of what dough feels like when it’s risen right. People came—some without addresses, some without hope, some with both—and said thank you like a prayer and sometimes not at all. I didn’t need the words. I needed the work.

One afternoon she stood in the line, thin under a cheap coat, hair pulled back like a thought she couldn’t finish. Without the war paint of money, Victoria looked like a girl who had stayed up too late and believed too many lies. She froze when our eyes met. I thought she would turn away. She didn’t.

“I…” she began, and then tears fell the way they do when you aren’t performing. “I don’t know why I did it. I thought… I was so sure I knew the shape of the world. I wanted to be seen so badly I forgot how to see.” She swallowed. “I hurt you. I hurt him. I don’t know how to fix what I broke.”

I held a ladle like it was a gavel and looked at the woman who had slapped me in a room that smelled like money and orchids. The woman in front of me was not that woman. She was less and somehow more. You can tell when a person’s story has cracked them open in a way that light can use.

I didn’t hug her. Forgiveness offered too easily is a lie people use to keep their hands clean. I filled a bowl with soup, placed a piece of bread on the tray, and put it into her shaking hands. “Everyone makes mistakes,” I said. “Forgiveness is easy. Living in a way that doesn’t require it—that’s the hard part. Eat. You look too thin.”

She nodded and sat at a metal table where men mended with spoons. She ate. I turned back to the line. Service is a kind of prayer; you say amen with every ladle.

The noise around us dimmed over months, the way summer always gives up eventually to a season that minds its own business. We went back to the city. A new quiet moved into the penthouse—not the expensive kind, the earned kind. Liam came home with less heat in his shoulders. He stopped structuring his sentences like pitches and started telling me small things again: the funny noise in the elevator, the man in the park who walked his cat, the app’s latest update that fixed a bug most people didn’t know existed.

He asked once, almost shy, “Do you regret it?”

“What—working myself into old hands?” I teased. “Raising a boy on beans and grit?”

“No.” He smiled. “Coming to New York.”

I looked at the city like it might answer for me. The skyline does that thing at dusk—turns into a confession of light and steel. “No,” I said. “I regret the times I mistook pride for strength. I regret the years I thought asking for help was the same as failing. But this? Watching you stand up in a room that worships money and choose a person over a performance? No, Liam. That’s not the kind of thing a mother regrets.”

He nodded like a man who had been waiting for permission he didn’t need.

The soup kitchen asked if I’d help on Thursdays too. The dishwasher had quit and the machine was old and screaming for retirement. I rolled up my sleeves and found the rhythm again—rinse, rack, push, steam, dry. I started bringing in the muffins I used to bake for miners when paydays came and men remembered to splurge on sugar. “We’ll call them Connie Cakes,” one of the volunteers joked, and everybody liked the name except me. “Call them muffins,” I said. “I’m not a brand.”

We got a new volunteer one day—a college kid with a shy smile and a tattoo of a mountain on his wrist. “My dad worked the mines,” he said when he noticed I’d noticed. We traded stories while chopping celery. People think coal is just a rock. It’s also a community. He’d never been to West Virginia, but the way he said “Dad” made the miles between his mountain and mine smaller than a map suggests.

Part III

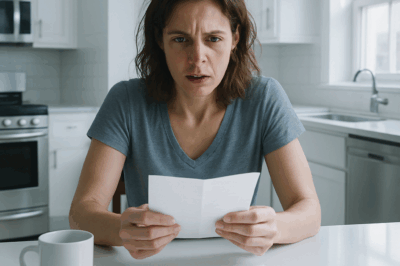

The phone rings differently when it’s the past calling. Sometimes it uses your own voice. Sometimes it uses the voice of an old friend. Sometimes it uses no voice at all, just a letter with a state crest and the question Do you wish to renew? The restraining order expired after a year. Mark had not come close to me, not called, not breathed in my direction. I held the paper in a beam of kitchen light and felt calm. “No,” I wrote. “I do not wish to renew.” Some doors you lock forever. Some you simply stop needing.

He didn’t resurface for us. He did for a few creditors, I heard, the way a shark fin resurfaces for a second and then remembers its nature. There are men who lean so hard on lies that the truth makes them fall over. I put his name in a drawer labeled Not My Problem and closed it.

The museum called months later—different museum, different room, different reason. They wanted to host a fundraiser for my son’s nonprofit arm, the part of his company that offered free financial coaching and small, kind loans to people the banks call too risky and my heart calls familiar. “We’d be honored if you’d say a few words,” the director said. “Just… tell your story.”

“I already did,” I said before I could stop myself.

“Not the slap,” she said, soft. “The other one.”

So I stood in a room with a floor polished enough to confess every scuff and told a story about a kitchen light and a boy with a pencil and a girl behind a diner counter learning how to make coffee that didn’t taste like defeat. I talked about loans with sharks in them and a son who decided to build a raft. I forgot to be nervous. When you have nothing to sell, speeches are easy.

After, a woman with pearls smiled at me the way people smile when they’ve just remembered their own mother’s hands. “You must be so proud,” she said. I thought about the morning Liam had walked to a microphone and said what needed saying. I thought about the night he fell asleep on my shoulder like a boy who carries too much and finally put it down. “Pride is too small a word,” I said.

The next Sunday I went back to the soup kitchen and Victoria was there again, this time not in line but behind the counter, hair tied back in a way that looked intentional, sleeves rolled. She washed pots like a woman who has made friends with a bruise. She looked up, met my eyes, and nodded—the plain, honest nod of a person who is choosing the long version of repair. We did not speak beyond the practical: more salt, please; where’s the ladle; can you hand me that tray; careful, hot. Work is a language that forgives accent.

I sent a letter to the high school in West Virginia with a check that would cover “rules” for a long time. I asked them to call it the Thomas and Connie Fund. Mr. Brennan had retired; the new principal wrote back and said she’d taught Liam and always knew he would set something on fire—in a good way. “We’ll post it in the office,” she said. “We’ll make sure every kid sees it.” I pictured a boy standing with a coat in his hand, listening, and I prayed that no one like me would need to wear their funeral dress to ask for mercy again.

One afternoon, Liam took me back to the museum where the wedding had been. It was closed to the public. “I wanted to see the room,” he said. I didn’t want to. I went anyway. The space echoed the way it had that night; marble remembers. We stood together. “I can’t stop thinking,” he said, “about how you apologized before anyone asked you to. About how your first instinct is always to help. I’m trying to build a company that does that. I don’t want to forget why.”

“Then don’t,” I said. “Let your hands get dirty sometimes. Sit with the ones who don’t have anyone to introduce them to a room. Money’s loud. Kindness whispers. Make sure you can still hear the whisper.”

He swallowed hard. In the reflection of the glass case nearby I saw us—gray hair and good suit, old hands and new. People like to pretend legacy is money that walks. Legacy is how your children use their hands.

We left by a side door. Outside, the city did its relentless glitter. A woman passed walking a dog that looked like a small rug. A man yelled at a taxi the way you yell at weather. Liam laughed, and the sound was so clean I had to look away.

At church the next month, the pastor preached about the prodigal son and the older brother who never left home. “We spend so much time on the leaving,” he said, “we forget the staying is work too.” I thought of myself at that kitchen table making lists, of my hands in dishwater, of nights that lasted longer than the dark. I thought of Victoria, washing pots with her head down. I thought about how forgiveness is not a door you open once but a path you keep sweeping.

After the service, a young man—tattoos, nervous—stopped me just outside the heavy wooden doors. “Ms. Lawrence,” he said. “My mom… she worked like you. I wasn’t… good.” He forced a laugh that hurt. “I watched that video. I called her. I’m trying.”

“Good,” I said, and put my hand on his shoulder the way mothers do when they mean You can. “Keep trying. Call her again.”

Part IV

On an ordinary evening, the city lights stitched themselves across the sky and I stood on the balcony with a photograph that had traveled rolled in a drawer since West Virginia. Me and Thomas—black dust in our hair, smiles like we hadn’t learned to be careful of them yet. “What are you thinking about, Mom?” Liam asked, stepping out into the chill.

“These hands,” I said, holding them up to the light so the years could show—the spots, the lines, the softened calluses that never quite let go. “They were once black with coal. Then raw from lye. Now they cut onions and hold grand ideas they don’t quite understand. But they built a good man.”

He lifted my hands to his face and kissed both palms, as if sanctifying an altar. We sat. The city hummed like a distant river. He talked about nothing important and everything that mattered—the neighbor’s baby who cried with gusto, the elderly doorman who knew everyone’s name, the way the app had been translated into a language that would reach a village his investors couldn’t find on a map.

“I want to tell you something,” he said at last. He looked like a boy trying to thread a needle. “When I said—when I ended it—that wasn’t a performance. I didn’t think about the press, or the money in the room. I thought about listening outside a principal’s office. I thought about you selling stamps and a watch you loved. I thought about you making coffee at dawn. I thought… I thought about your hands.” He took a breath. “I want to live in a way that doesn’t require forgiveness. I won’t always succeed. But I want that.”

I laughed softly. “Then eat your vegetables and be on time,” I said, because mothers must dilute profundity with practicality or the world topples.

We didn’t speak of Victoria again that night. We didn’t need to. Some stories don’t end with courtrooms or grand apologies. They end with a woman serving soup and a nod over a steaming pot, with a son who has learned the names of the quiet things.

If there is a moral, it isn’t complicated enough for a museum wall. Hands build many kinds of empires. I’ve seen men build ones of steel and stone and numbers so big they require new words. I’ve seen women build children out of biscuits and bedtime, out of yes ma’ams and not yet, baby. The world throws parades for the first and forgets to clap for the second. That’s fine. Bread rises in the dark. So do boys.

When I go back to West Virginia now, the mountain looks smaller. It’s not. I’ve just learned which parts of it are mine to climb. I visit Thomas’s grave and leave him a pebble from a city he never saw and a story about his son that he always knew. I drive past the diner and the laundromat and the house with the azaleas that refuse to die. I sit with the women who still work the early shift and we trade recipes and history and the kind of news that fits in a palm.

Before I leave, I stop at the high school and look at the Thomas and Connie Fund posted in the office window. A mother reads it while her boy shifts his backpack from one shoulder to the other and tries to look like he isn’t listening. I catch his eye and smile. He smiles back, quick, like a secret. “We have rules,” the world says, and sometimes the world also says, quietly, “We can bend them for mercy.” Teach the world to like that second voice better.

On the way home, my phone buzzes. A text from Liam: Soup tonight? It’s not a request. It’s a ridiculous, extravagant blessing. I type back: On my way.

In the kitchen, I take the heavy pot down. I chop onions. My eyes water the way they always have. I stir. I taste. I add a pinch more salt. Steam curls into the air like a prayer. The door opens. My son steps in. He kisses my cheek where, long ago, a hand once tried to write a different story. It didn’t take.

We sit. We eat. The city outside keeps being itself. Inside, we keep being ourselves. That’s the ending, if you need one: not a headline, not a looped video, not a marble hall echoing with other people’s money. Just a kitchen, a son, a mother, and two sets of hands that remember what they’re for.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Karen Banned Kids from Trick-or-Treating on HALLOWEEN — So the Neighborhood Turned Against Her!

Karen Banned Kids from Trick-or-Treating on HALLOWEEN — So the Neighborhood Turned Against Her! Part 1 I never thought…

My Son Got Married Without Telling Me — His Wife Said “Only Special People Were Invited,” So I…

My Son Got Married Without Telling Me — His Wife Said “Only Special People Were Invited,” So I… Part…

MY SON ORDERED ME: OBEY HIS WIFE OR LEAVE I SMILED, TOOK MY SUITCASE, AND WALKED AWAY…

MY SON ORDERED ME: OBEY HIS WIFE OR LEAVE I SMILED, TOOK MY SUITCASE, AND WALKED AWAY… Part I…

After Three Years of Silence, I Received a Letter from My Dad. But When I Looked Closer…

After three years of silence, I finally received a letter from my dad. At first, I thought it was the…

Mom Said We’re Doing Thanksgiving With Just The Well-Behaved Kids Yours Can Skip This Year.My Child

Mom Said, “We’re Doing Thanksgiving With Just The Well-Behaved Kids — Yours Can Skip This Year.” My Daughter Started Crying….

My Parents Chose Dinner With My Brother’s Girlfriend Over My Life — Then My Letter …

My Parents Chose Dinner With My Brother’s Girlfriend Over My Life — Then My Letter … Imagine lying in a…

End of content

No more pages to load