My Son Said Find Your Own Place After 50 Years — So I Sold the House and Moved to Monaco

Part One

I was halfway through folding the napkins when Isabelle, my daughter-in-law, stepped into the doorway of my sewing room and announced—in the same bright voice she used to ask a server for sparkling water—that she and Marcus had been “talking about the living arrangement.”

She didn’t say your home. She said the living arrangement, like the three of us were items on a spreadsheet whose cells needed better alignment.

“It’s his childhood home,” she added, tilting her head toward the hallway where the growth marks still climbed the doorframe. “His inheritance, technically. We’ve had such a good run here. But maybe it’s time you found your own little place—something more…appropriate.”

The word landed with a soft thud and an iron heel.

I didn’t argue. I didn’t list the gutters I’d paid to have cleaned in October, or the deck boards I’d resealed in May, or the wrinkled article from the local paper framing my garden under the headline A Living Quilt. I didn’t mention the thirty Christmas trees I had stood in our bay window or the five pies I could make without looking at a recipe or the sound of little feet thundering to the table when I sang “Grilled cheese!” I didn’t tell her that putting a woman in a box called “age” tells you less about the woman than it does about the person holding the lid.

I asked one question: “Where is Marcus?”

“In the shower,” she said. “We’ve already talked about this. He agrees.”

When he appeared, hair damp and strange in expensive athletic clothes, he used the same voice he’d used at fifteen to negotiate curfew: overly reasonable, allergic to detail.

“We’re adults, Mom,” he said. “We need our own space. You can’t live with me forever. There are great senior places. Sunrise Manor has an art studio and movie nights. It’s…independence.”

“Independence?” I said. “For whom?”

He winced. “Please don’t make this harder than it has to be. The house is in my name.”

It was. After David’s heart attack five years earlier, when grief made everything look like fog, I had signed transfer papers “to make things easier.” Marcus had held my elbow as we walked out of the attorney’s office, and I had tried to believe that what he wanted and what David would have wanted were the same.

“End of the month,” he said now. “We’ve already booked an interior designer.”

It was January fifteenth.

“Well,” I said, “we’d better move quickly then.”

He beamed. “I knew you’d understand.”

When they left for pilates and golf—modern life’s version of church—I put away the napkins, made a cup of coffee, and sat alone in the kitchen where I’d lived a life. I looked at the herb pots lined beneath the window—basil, rosemary, thyme—the leaves turning toward winter light they didn’t ask permission to love. I heard David in my head say, as he always did when we were about to do something impractical but necessary, Tie down what you can. Don’t build a gazebo in a storm.

So I tied something down. I opened my laptop and typed housing market analysis into the search bar. Then best time to sell in a seller’s market. Then, because sometimes you let an idea out just to see whether it will come back to you, cost of living Monaco.

Three hours later, I had Jennifer Morrison, the best agent in our county, scheduled for a walk-through. By that evening, I had met the face in the mirror I had been missing: Geneva Walsh (Genie since age seven, when I informed my brothers I granted wishes to the polite), home owner, widow, grandmother, pianist, gardener, and absolute fool no longer.

“Mrs. Walsh,” Jennifer said when she walked through my front door and took in the crown molding, the tiger oak floors and the way light poured like honey through the windows, “you have a gem. If you’ll let me stage it lightly and photograph it properly, we’ll have multiple offers by Monday.”

“Friday,” I said. “List it Friday.”

She blinked, did quick mental arithmetic, then nodded. “Friday it is.”

On the second day of showings, the Hendersons walked in—a couple in their fifties with warm eyes and careful hands. They paused in my kitchen like it was a chapel. “Someone loved here,” the wife said, tracing the doorframe where pencil lines marked Marcus—6, Marcus—10, Marcus—12.

“We did,” I said, and meant it. “I hope you will, too.”

Their offer came with a letter. They promised to bring life to the garden I had spent thirty years coaxing and reviving. They promised to host big Sunday dinners and make the rooms ring with grandchildren’s laughter. They promised that if they renovated, they would keep the wainscoting in the dining room because it felt like a hug. They were not the highest bidders, but they were the right ones. Jennifer’s eyes met mine; she didn’t have to sell me. The papers were signed at noon on a Thursday. The funds—four hundred sixty-five thousand dollars of fond farewell—were wired into the account Richard Chen had managed since David and I chose prudence early and curiosity always.

In the corner of my kitchen, two envelopes waited under a mug that read Grant Your Own Wishes. In Marcus’s letter, I wrote facts. The house has sold. The closing is complete. You and Isabelle asked me to find my own place. I have. My flight leaves at three. In Isabelle’s, I wrote gratitude. Thank you for teaching me that “appropriate” is a word only cowards use to stay comfortable. I won’t use it again.

At one in the morning, with the house quiet and my suitcases locked, I sat with Richard looking at a number I had never seen assigned to my name: $2.1 million. David’s caution. David’s trust. David’s parting gift. “You could live well anywhere,” Richard said. “Pick joy.”

Monaco, I almost said aloud, tasting the word like champagne. I booked a furnished apartment on Avenue Saint-Charles the way other women buy a pair of shoes they know will change how they walk. Celeste at Riviera Properties sent videos of sunlit rooms and an impossible terrace that wrapped a view of sea and palace like ribbon around a gift.

“Why Monaco?” Helen from next door asked over lunch when I told her. “Because when I was twenty-four, David and I ate spaghetti from the pot and promised that if we ever could, we’d watch the sun rise over a harbor that didn’t smell like low tide,” I said. “Because my son thinks ‘appropriate’ is a fence. Because I am sixty-eight and I want my last years to look like a love letter to the girl who never once made the top of her own list.”

Helen raised a glass of Sauvignon Blanc. “To love letters,” she said.

On January thirty-first, while the movers loaded my grandmother’s china cabinet and the threadbare armchair David had loved but I did not, Marcus padded downstairs and stared at the empty outlines on the floor. “Mom,” he said, bewildered, “where’s all your stuff?”

“Gone,” I said.

“Gone where?”

“My new place.”

He looked at his watch, at Isabelle, at me—searching for the version of this story he had been told he would be in charge of telling. He had been given a script in which I cried and clung and he graciously allowed me to stay; I had tossed the script in the trash next to the expired coupons and taken the lead. “Marcus,” I said, holding his face the way I had the first time a nurse placed him slippery and furious in my arms, “you told me to find my own place. I did.”

Isabelle’s mouth opened and closed like a trout’s. “But—Sunrise Manor—Monday—tour—”

“No tour,” I said. “No Manor.”

“Then… where?”

“Monaco.”

Silence. You could have dusted the hallway with it and not missed a mote.

“You’re joking,” Isabelle said finally.

“I am sixty-eight years old,” I said, “and done making jokes that make other people’s lives easier to hear.”

The taxi driver, a woman with a braid like a rope, loaded my suitcase, asked “Airport?” and, when I said “International terminal,” gave me a thumbs-up the size of a promise. I hugged my son. He cried. I cried. The house did not. Houses watch a lot and learn patience; it understood it was being loved forward.

On the plane, a flight attendant in a polished chignon and red lipstick handed me a glass of champagne and asked, “Celebrating something?”

“Freedom,” I said, and drank.

By mid-morning, I was walking into a lobby with marble floors and a concierge named Henri who said, “Welcome home, Madame Walsh,” like he meant it. And when Celeste let me into 4B and the terrace wrapped me and the harbor in the same breath, I thought, Appropriate, at last.

For three months, I built routines like scaffolding around a new self. I learned to order coffee in French and to ask for fennel at the market without pointing. I walked the coastal path until the view from Cap-d’Ail to the Prince’s Palace felt like a hymn I could sing from memory. I learned people’s names—Madame Dubois from 3A who hosted a salon on Thursday nights where a Moroccan poet and a Welsh violinist argued kindly about whether beauty requires truth; Michel who ran the bistro on the corner and served only the four dishes he could make flawlessly; Sarah from London who had left accounting at seventy-one to sculpt, and when I said at seventy-one?, laughed and said, “Darling, I intend to make up time.”

My first birthday in Monaco, a man at watercolor class painted me as a map of bright colors and called it “Woman Beginning.” I framed it and hung it over the small desk where I wrote to David every evening in my head and to Marcus once a week by email. He did not answer at first. Then he did. Then he called.

“Mom,” he said, thin across the ocean, “Isabelle left.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, because compassion is free even when it isn’t owed.

“I’m in a one-bedroom. I never learned how to budget for real. I thought—” He didn’t finish. He didn’t need to.

“We can talk,” I said. “We can always talk.”

We did. He told me the truth for the first time. I told him mine. He said he was in therapy. I told him I was in watercolor. He apologized without asking for anything. I forgave him without sacrificing anything. We learned to be a mother and a son on equal footing, where love did not require either of us to be smaller than we were.

By summer, when he came to visit, I had a favorite table at a restaurant where the owner scolded me for ordering a dish that wasn’t perfect today and then brought me something else that was. We stood on my terrace and counted yachts and I said, “I want you to know: if I ever move back, it won’t be to take care of you. It will be because I want to.”

“I know,” he said. “I don’t want to be a son who asks his mother to be smaller so he doesn’t have to be bigger.”

He told me he had been offered a job in Atlanta and that he wanted to say yes because it would be his and not a favor attached to a Christmas invitation. He said he was proud of me. I said I was proud of us.

One afternoon, an email arrived from Carol Henderson with photos: my climbing roses blooming over the back fence like audacity, the herb garden green and obedient, the kitchen windows catching morning as well as they always had. “If you ever come back,” she wrote, “we’d love to have you for coffee in the garden you planted.”

“Perhaps next spring,” I replied, attaching a picture of a Mediterranean dawn so blue it hurt. “Bring cuttings. I’ll start a Walsh rose in Monaco.”

Part Two

I would love to tell you that leaving solved everything and that Monaco washed me clean and that no one ever asked for anything again. But life is knotted more intricately than that. People do not become new by moving zip codes. Some people double down.

Three weeks after I arrived, a call came from a number that began with +1 and the three digits I knew as home. “Mrs. Walsh?” a nervous voice said. “This is Andrew from Oak & Maple Financial. I’m calling about a past-due amount on the home equity line of credit attached to your property at 14 Orchard Lane.”

“My property?” I said. “I sold 14 Orchard Lane three weeks ago.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he said, papers rustling. “Our records show payoffs received from closing for the primary mortgage, but the HELOC tied to your son’s company was not included. We sent notice to the address on record. There’s a thirty-day acceleration clause in the event of transfer. If we don’t receive payment, we’ll have to file a notice of foreclosure against the property. I—sorry—I know this is not what you want to hear.”

“Nor,” I said, looking past Henri arranging flowers in the lobby to the harbor full of boats that did not have patience for wind, “what the Hendersons deserve to receive.”

I made three calls: one to Jennifer, who said “Absolutely not,” with a ferocity that reminded me why she’d sold half the county; one to the title company, who escalated my call with the haste reserved for actual emergencies; and one to Marcus, whose voice when he answered was already half apology.

“It’s mine,” he said before I could ask. “The line of credit is under my company. I didn’t tell you because—well, there’s no good reason. I thought you’d overreact. I thought it would be fine. I thought—”

“That thinking is expired,” I said. “The notice is in your name. The Hendersons are protected by the title insurance, and the bank is going to accelerate the note and come after you. Call a lawyer who specializes in these things. Not Thomas. This is your problem, not mine and certainly not the Hendersons’. And Marcus? Do not let this touch them. Fix it.”

He did. Perhaps because he had learned that consequences have a schedule louder than denial. Perhaps because he had stood in a one-bedroom apartment looking at a bank statement and finally understood the math of pride. He paid the line off with money he did not have to spare. He wrote the Hendersons a letter so heartfelt that Carol sent me a photo of it with a line that said, “He is learning.” He did not ask me for help. He did not blame me. He sent me a text that read, Due-on-sale clauses should be spelled in neon, and I replied with an emoji wearing sunglasses because sometimes love looks like sarcasm.

After that, the calls turned less frantic. The grandchildren’s voices filled my phone at odd hours with the sound of new science projects and pirouettes done toward the sea, with the telling of a joke that did not translate but made me laugh because laughter is bilingual. Olivia’s voice was steadier. She told me small things she was proud of: balancing a budget that used to terrify her, enrolling in night classes in lighting design, saying no to a dinner she didn’t want to attend without apologizing five times. “Sometimes I stand in the grocery store,” she confessed, “and choose the cheaper bread and feel as triumphant as if I had climbed a mountain.”

“You have,” I told her. “You just can’t see the altitude from inside your own chest.”

Diane called me exactly once. “We are hosting Max’s birthday,” she said. “Olivia tells me you will not fly back. It would mean a great deal to him.”

“You don’t get to use the children to triangulate,” I said. “If Max wants to FaceTime me to blow out candles, he can. I am not flying back to admire a boy you taught to believe that money is love. He knows better now, and that must be very inconvenient.”

“People our age,” she began.

“Don’t,” I said, and hung up.

In Monaco, I sat on the terrace at ten o’clock at night and watched the lights across the harbor make a necklace of the hills. I went to the opera in a black dress that made me feel taller. I cried during the overture because David should have been there to whisper pretentious things about tempo and then get choked up, too. I met a man at the bookshop who asked me to coffee and did not mention golf once in two hours. He was a widower named Luca with a laugh like a handclap and a careful way of placing his mug on the table. We went walking the next week and I did not tell anyone, not because I was ashamed, but because it felt like a beginning I wanted to belong to only me for a while.

Spring came. The bougainvillea on the building rose from a polite blush to a riot. Henri began bringing roses from his sister’s garden on Saturdays “for Madame’s vases.” A postcard arrived from Carol with the first fully opened ‘Eden’ rose in my old side yard taking up the whole frame. For your new terrace, she wrote, as if bloodlines could be coaxed across oceans.

On my birthday, Olivia sent me a photo of a small cake with two candles shaped like a six and an eight. “Not age,” she wrote, “miles traveled.” Marcus FaceTimed from a kitchen with appliances that matched but didn’t brag: white cabinets, a coffee maker thank God, and a calendar with “Grandma call” written twice a week. Sophie showed me a painting of a woman in blues and golds. “It’s you on your balcony,” she said. “I’m calling it ‘Appropriate.’”

In June, the Hendersons hosted their first garden party and texted pictures that made me homesick and happy: my peonies—no, their peonies—exploding like fireworks; a platter of deviled eggs on my old blue plate; a child—one of theirs? a neighbor’s?—holding a frog like a secret. I sent back a photo of my terrace with pots of rosemary and thyme and a small pot of basil learning the language of Mediterranean sun. We share a garden now, I wrote to Carol. It is long and narrow and reaches across the water.

By September, the apartment I had rented the way people try on hats was too small for how large my life had become. I stood in a new place with a real estate agent named Simone who spoke with her hands and told me the story of every tile. “You see?” she said, opening the shutters to a sweep of sea so shocking it made me whisper. “Here, the light arrives before you wake and waits on the terrace until you have finished your coffee. It is a faithful friend.”

I bought it.

“Permanent, then?” Helen said on the phone when I told her. “Permanent enough,” I said. “I have learned the only permanent thing is the way I have finally begun to belong to myself.”

Olivia and the children came in October for ten days that smelled like salt and bread. We ate mussels and frites and said yes to dessert more often than is reasonable. Max insisted on trying to tell jokes in French—badly, bravely—and delighted the man at the next table who told him he had excellent comedic timing and should practice his r’s. Sophie painted the harbor and then insisted we take the painting down to the concierge desk for Henri to admire. “Tell him it’s a rose,” she said solemnly. “Tell him it came from a house that is not a house anymore but is still a garden.”

On their last day, Olivia and I sat on my terrace with coffee and the kind of silence that is not empty. “Do you ever regret it?” she asked, looking out at the line where sea meets sky.

“Leaving?” I said. “Yes. No. I regret that I had to.”

“I regret that I made you feel like you had to,” she said. “And I am grateful you did. Because if you could do this at sixty-eight, I can do anything at thirty-six.”

We watched a yacht try to moor in too much wind. It bumped once, twice, and then, with adjustments and advice shouted in three languages, came to rest alongside a dock that had seen enough boats to know the difference between panic and patience.

“Do you think Marcus will ever move here?” she asked next, smiling.

“Monaco?”

“No. To…whatever this is. Choosing himself without borrowing someone else’s life to do it.”

“Maybe,” I said. “He’s learning to make dinners that don’t come from a number on a speed dial and to buy bread that’s enough and to apologize without asking for anything. That’s graduate work.”

She laughed, wiped the corner of her eye, then said, “Diane invited herself to dinner last week and said, ‘People our age.’ I told her nothing useful happens after that phrase.”

“She will hate me,” I said, and we laughed in unison long and wicked.

On the day Marcus called to say his divorce was final, I sent him a photo of the sea and a line from a poet Madame Dubois loved: Peut-être que le vrai courage est de renaître. Maybe true courage is to be born again. He responded with a picture of him holding a wooden spoon. Dinner, he wrote. Edible. I sent back clapping hands. He sent back a picture of a calendar with “Call Mom” written in ink.

On the anniversary of the day Marcus told me to find my own place, I put on a navy dress and my pearls and walked down to the market to buy exactly six peaches because Madame Dubois had taught me never to buy fruit you cannot carry home in your own two hands. I stopped at the florist and bought a single rose and told Henri, “For the desk, s’il vous plaît,” and he said “Bien sûr, Madame,” like he had been expecting exactly that.

Back on my terrace, I lifted a glass toward the harbor.

To the boy who learned that houses are not love and that love does not live in houses.

To the girl who grew up to be me, who believed other people when they told her she was convenient, and then moved to a place where the only person she had to convince was the one in her mirror.

To David, who filled our bank accounts with safety and our days with foolishness so I could fill my mornings with this.

To Isabelle, who taught me what happens when you hand someone your permission; may she learn to write her own.

To gardens that bloom in two countries and to the women who cross pollinate them.

To appropriate, at last.

That night, I dreamed of my old kitchen. The butcher block island was scrubbed clean, the windows open. The morning light came through the glass like mercy. Voices drifted in from the garden. Somewhere in the dream, I was holding coffee and a set of keys that did not unlock anything but myself.

In the morning—my morning, the one I chose—the sea was exactly as blue as it had been the day I arrived. The sky had the nerve to be even bluer. I picked up the phone and called Marcus because it was Tuesday and we call on Tuesdays and because sometimes family is the calendar you make after you stop living by other people’s.

“Mom!” he said, and I could hear a pot boiling on his stove and the radio playing a song he used to hate and now loved and the sound of a life which was not what he had planned, which is to say perhaps it was finally his.

“I had a dream about soup,” I said.

“Me too,” he said. “I’m making some now.”

“Appropriate,” I said.

We laughed, and then we talked about nothing, which is the richest subject I have ever earned.

Outside, the Mediterranean went on doing what it does best: reminding anyone paying attention that all horizons are fictional until you walk toward them.

END!

News

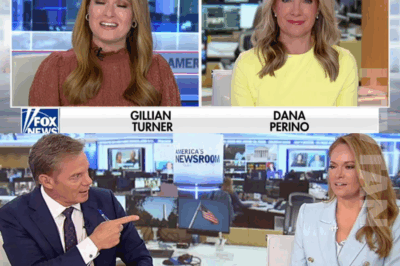

“She doesn’t deserve this kind of baseless criticism.” Dana Perino steps up for Gillian Turner after the America’s Newsroom fill-in host faced harsh backlash. Expressing full confidence in Turner’s journalistic integrity, Perino gently encouraged the mother of two to rise stronger next time. But what touched viewers most wasn’t just her words—it was the heartfelt gift Perino gave Turner, something far greater than any pep talk. A powerful reminder that at Fox News, real support runs deep. CH2

In the fast-paced world of cable news, where every word is scrutinized and every gesture analyzed, the recent controversy surrounding…

My husband to mistress: “Can’t wait to ditch the child support and run away with you”. CH2

My husband to mistress: “Can’t wait to ditch the child support and run away with you” Part One I didn’t…

My Sister-In-Law Banned Me From Family Dinner—Where My Husband Planned To Announce Our Divorce. CH2

My Sister-In-Law Banned Me From Family Dinner—Where My Husband Planned To Announce Our Divorce Part One The hostess’s sympathetic smile…

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call. CH2

I Gave My Daughter Our Family Home, Her Husband Made Me Sleep In The Garage—Until I Made One Call …

BREAKING: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in America had dared to ask to do before. CH2

LATEST NEWS: Kayleigh McEnany gave birth to her third daughter, she asked the doctor to do something no mother in…

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour. CH2

After My Children Put Me In A Nursing Home—I Purchased The Facility And Changed Their Visiting Hour Part One I…

End of content

No more pages to load