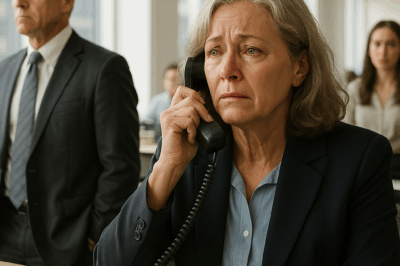

My Son Pushed Me at the Mother’s Day Dinner: “That Seat’s for My Mother-in-Law—Get Out.” So I Did…

Part 1

I arrived five minutes early, cradling the pecan pie with both hands so it wouldn’t tilt. I’d wrapped the edges in foil the way I always did to keep the crust crisp and the filling glossy. Everett loved the way I made it—just enough salt to wake the caramel, just enough sweetness to coax out the butter. His favorite since he was ten, when he’d sit on the counter, toes tapping the cabinet, waiting to lick the spoon. I stepped into the house without knocking.

It used to be mine, too.

Roast and wine and perfume hit me first. The dining room’s laughter lifted and folded back down like a blanket I wasn’t under. Clarissa’s in-laws—Rosa and her clan—filled the space like they had paid the mortgage themselves. Clarissa stood by the buffet with her father, leaning in, a flute of something sparkling between her fingers. Rosa, her mother, was already seated, smiling into a glass of red. I looked around for my boy.

No one looked back.

At the head of the table sat an empty chair—its tall back carved with the same leaf pattern Everett used to trace with a cereal spoon as a child. I took a slow step toward it, balancing the pie, already wondering if they’d remembered dessert plates, if the whipped cream had been thawed enough to spoon.

Everett moved fast. Too fast for it to be casual. He stepped between me and the chair, a smile stitched sloppily onto his face, one that didn’t reach his eyes.

“That’s for Rosa,” he said quietly. “You can sit in the kitchen.”

I blinked. “What?” I knew what. I just wanted the question to slow time enough for him to hear himself.

He didn’t repeat himself. He didn’t need to. I didn’t move. So he did.

It wasn’t a shove hard enough to bruise, only a deliberate push, like redirecting a shopping cart. My hip clipped the hutch; the pie box bobbled; my knee kissed the wall with a crack I felt in my teeth. I caught the pie.

No one gasped. No one reached for me. Clarissa said something about the roast drying. Rosa sipped. Someone laughed at a story about a golf course. I steadied my breath, both hands still holding the pie. He didn’t look at me again.

So I turned and walked out.

Down the hall, through the door, past the porch swing I’d sanded and stained in 2004 while Everett studied for algebra. Past the bush I planted for Mother’s Day the year he’d made me a card from printer paper and green crayon. I walked into the driveway I’d helped him pay for with the second job he never liked hearing about.

I didn’t slam the door. I didn’t cry. I put the pie on the passenger seat and sat behind the wheel until the heat of the foil cooled against my palms. That old porch light flickered across the lawn—the bulb I’d mentioned needed changing the last time Everett dropped by and nodded, already halfway back to his car. I pressed my hand to my knee. I wasn’t trying to ease the ache. I was making sure I could still feel anything at all.

It wasn’t always like this.

When Everett was five, I worked nights in oncology and days cleaning the school so he could stay in a better district. I napped in my car between shifts, head tipped back, mouth open, dreaming of nothing but making it to payday. At fifteen, he wanted the early-college prep program that cost more than we had. I sold my engagement ring—the last thing of Franklin’s with shine left in it. Everett never knew. He only beamed when the acceptance letter arrived and said, “Told you I’d get in, Mom.”

At high school graduation, cap crooked, cheeks wet, he pulled me in tight. “You’ll always live with me,” he said into my hair. “You’re the reason I made it.” I didn’t ask for that promise. He gave it as if he had invented the idea of devotion.

And now, twenty years later, the same boy told me without flinching that I wasn’t welcome at his table. It wasn’t the push that hurt most. It was the ease of erasing.

I took the pie home and slid it into my refrigerator between a jar of pickles and a Tupperware of Sunday stew I’d made for myself. The quiet in my kitchen was honest the way silence sometimes is after a storm. I turned off the light, then turned it back on. Instead of going to bed, I opened the hallway cabinet and reached for the fireproof lockbox where I keep what matters: birth certificates, Franklin’s discharge papers, the deed.

The box wasn’t locked.

Inside, the envelope labeled “Home: Title & Deed” was gone. So were the notarized letters Franklin and I signed when we refinanced in 2001. I sat on the floor, the lockbox tipped into my lap, and tried to reason with myself. Maybe I’d moved them during spring cleaning. Maybe I’d given them to a tax preparer. Then my memory lit up like a match.

Three weeks ago, Everett had shown up at noon with a Starbucks and a manila folder. “It’s just a tax form,” he’d said. “Routine. You know how the county flags old records.” I was on my knees cleaning baseboards, and the smell of lemon cleaner always makes me generous. I signed in a dozen neat places. He kissed my cheek and left before the ink dried.

I wanted to be a woman who didn’t need to suspect her own child. But wanting doesn’t make any of us safer.

The county recorder’s office the next morning was cool and beige and efficient. The clerk printed the updated records in under two minutes. When she slid them under the glass, I scanned each line twice, then again, as if seeing could undo what had been done.

There it was. A new deed, recorded, stamped in a blue that looked almost cheerful. Co-owner: Everett Moure. Co-owner: Rosa Martinez. My name was still there, but no longer primary. A new clause, deliberate as a bruise: any changes to the property require signatures of all parties.

My throat tightened, but my hands didn’t shake. I folded the papers as if they were a dress I’d wear again, thanked the clerk, and stepped out into the white slap of noon. The hood of my car was hot. I pressed my palm to it and breathed until the air went back to being air.

Then I took out my phone and dialed a number I hadn’t used in years.

Thomas Greer handled Franklin’s will when we were young and poor and trying so hard to do something right. He handled the mortgage title transfer when we finally paid the house off. He joked once that it isn’t paranoia if the wolves are real. I’d kept his card behind an old photo of Franklin in my wallet like a charm.

He answered on the second ring, voice lower than I remembered.

“I need help,” I said. I didn’t explain everything. I offered enough for him to hear the shape of it.

“Monday,” he said. “Ten o’clock. Quiet. No fee—for Franklin.” His little wheeze of a laugh softened the words. “And for you.”

Back home, I opened the cedar chest in my bedroom. Beneath quilts, letters, and one Easter card Everett had scrawled in crayon—“I love you Mommy”—was a sealed brown envelope. Inside lay the original deed, not a copy, not a scan. The original, drafted and notarized in 1998, with a clause Franklin had insisted on in his messy hand: No transfer of ownership permitted without written, signed, and witnessed consent by the primary title holder, Kalista Moure.

People forget ink is a witness.

I had more than paper. Two years ago, on a spring morning that smelled like coffee and cut grass, Everett and I sat on the porch. He bragged about a loan deal, hands carving the air. I’d teased: “Don’t you sell this house out from under me one day.”

“Mom, come on,” he’d laughed. “This house is yours. It’ll always be in your name.”

I’d saved the audio—just testing the voice-memo feature then. I called the file “Morning Coffee.” I hadn’t listened since. I played it that night. The sound of his voice made my stomach turn—not because of the promise, but because I no longer believed he knew what promises were for.

Sunday blurred into Monday the way time does when you hold your fear still. Thomas’s office hadn’t changed: dark wood, diplomas, a potted plant astonishingly alive. He greeted me with a nod and a file already open. No small talk. I slid the envelope across the desk and the flash drive with the recording.

He listened to one earbud, eyes flicking between the deed, the county printouts, and my face. After a few minutes, he sat back.

“We have more than enough,” he said. “They won’t see it coming.”

The process wasn’t loud. It was signatures and notarizations. It was Latin phrases that still do their job. It was reinstating the original deed and voiding the revised one on the basis of fraud and lack of consent from the primary title holder. It was filing with the county and getting a clockwork confirmation. It was a new clause I’d thought of for years but never written: upon my passing, the property transfers in full to the Eastbrook Single Mothers’ Scholarship Fund. No cousins to argue, no son to barter, no in-law to renovate my history into someone else’s nursery.

After we filed, I walked two blocks to the city office and declared change of occupancy. No shared living. No joint tenancy. “I live alone,” I said. The woman behind the glass nodded like she’d been waiting all day to hear someone say something simple and certain.

When I got home, the front door flew open so hard it whacked the wall. Everett stormed in, red-faced, fists tight at his sides, the way little boys do right before they learn what their hands are for.

“What did you do?” His voice snapped like a twig. “The bank froze the refinance. Rosa’s parents were going to invest. Now they’re—what did you do?”

I didn’t stand. I didn’t raise my voice. “I protected my home,” I said. “You gave it away too easily.”

“You went behind my back,” he spat.

I looked at him for a long moment. “No, son. You went behind mine.”

Rosa clicked in on high heels that announced a queen to a court. She held a plastic folder like it was a clutch. “This isn’t legal,” she said to the room, to the air, to the version of me she had invented. “You can’t erase people from property like that. We’ll take you to court.”

I reached for a plain manila folder on the side table and handed it to Everett. “Original deed,” I said. “Voice recording. The ‘tax’ papers you tricked me into signing, plus a sworn statement of the conditions under which you obtained them.”

He didn’t touch it. Rosa grabbed it, flipping, and froze when she saw the notary stamp, his signature, the dates. The silence between the three of us pooled in the doorway.

“You didn’t have to do this,” Everett said, like we were discussing a late RSVP.

I stood. My knee ached and my heart was steady. “And you didn’t have to lie.”

I walked them to the door. Rosa’s phone blazed with texts. Everett’s shoulders made a shape I didn’t recognize from the boy who once stood on his toes to put his kindergarten smock on its hook. I opened the door. They stepped out. I closed it quietly and locked it once.

They didn’t come back.

But the consequences did. In a town this size, people talk because it helps them understand the weather. Everett had lived too publicly to hide the changes. The business deal Rosa’s family had propped up fell apart without the house as collateral. Investment without leverage is faith, and faith without family is rare. Rosa moved into her parents’ condo “for a while.” Everett stayed in the house he rented, making calls that went nowhere. I didn’t ask. I just kept my coffee warm and my porch quiet.

Two weeks later, an envelope arrived from the Eastbrook Single Mothers’ Scholarship Fund. Inside: a letter on crisp paper. Because of your designation and contribution, we are renaming our annual housing grant the Kalista Moure Legacy Award. I sat on the edge of my bed with the letter in both hands until the feeling of it traveled through my skin and informed my bones: there are endings that are not defeat.

That afternoon, I began volunteering at the center—two mornings a week, then three. Mostly I listened. Sometimes I looked over paperwork that snarled when it should have smoothed. When someone asked how I kept my home, I said, “I didn’t let anyone else write the ending,” and then I taught them how to read the beginnings.

A Thursday later, Rosa appeared on my porch in oversized sunglasses, clutching a folder like a handbag. She rang once and let herself in with the old ease of a person used to being welcomed.

“Everett said you’d want to get a head start,” she chirped, laying papers on the entry table. “You know, before the move-in. We’re planning for July. It’ll be easier for the kids before school starts. Everett said you’d shift into the guest room. We’ll convert the master to a nursery eventually.”

I didn’t answer. She drifted into the study, her fingers grazing the spines of photo albums like she was shopping.

“We’ll need this space, of course. Hope you’re okay giving it up. It’s too dark for a bedroom, but we can knock down that side wall to open it up.” She tapped a frame. “These old photos—so sweet—but we’ll probably pack them up. Keep it minimal. Clean lines.”

The fake sweetness in her voice scraped every nerve. She wasn’t being cruel. She was being efficient. Logistics. Paint colors. Timelines. Not a life.

“I’ll let you process,” she said, walking out. “We’ll send a painter next week. Neutral tones. Don’t worry.”

The door closed behind her.

I went to the study and opened the bottom drawer. The folders slid open under my fingers: LEGAL; EVERETT; SCHOOL; FRANKLIN—PENSION. That night, I boxed every photo, letter, certificate, toddler drawing, and taped cardboard diorama of a rainforest that had once spilled glitter into the carpet. I set them in the hallway, not for storage, but for defense. I was done being surprised in my own home.

I slept for the first time in a week without dreaming of tables that had no chair for me.

Part 2

The first note came in careful slanted letters I hadn’t seen in too long: Sorry I didn’t say anything. I love you, Grandma. No return address, just a slip of notebook paper tucked into my screen door behind a flake of paint. I stood in the kitchen with it pressed to the fridge by the same magnet that used to hold her stick-figure families—Daddy, Mommy, Baby, and a dog we never had. I read those eight words twice. It wasn’t an apology for action. It was an apology for silence. The difference mattered less than I thought it would. Love is sometimes exactly the size of a sentence.

Days braided into something steady. I made lists and crossed off items I used to let linger. I planted herbs where Everett and I once stomped puddles. Basil took the sun like a compliment. Mint misbehaved, spilling over brick with joyful invasion. Something red I couldn’t pronounce stood upright like courage. I replaced the porch bulb myself and laughed at the tiny victory of light.

Marsha came by on a Thursday with a bag of oranges and that look best friends wear when they’ve learned enough to stop pretending they don’t worry about you.

“You going to let him back in?” she asked finally, stirring sugar into coffee strong enough to wake regrets.

The wind lifted the chimes Franklin had hung a lifetime ago. The space between notes seemed louder than the notes themselves.

“Not until he sees me as someone worth inviting to the table,” I said.

She nodded and didn’t press. That’s why we’d made it three decades—some wounds don’t ask for wrapping, just air.

At the shelter, the women started coming to my house on Saturdays to make lunch together. It wasn’t a plan. It happened the way yeast happens to warm water: slow, then inevitable. We traded recipes and stories and sunscreen for the kids. We peeled, chopped, kneaded. We taught each other the magic of a dish that tastes like home even when you’re two buses away from everything you’ve known.

One noon, the front door opened to laughter and the shuffle-thud of small sneakers. Three women came in carrying salads, casseroles, and one toddler half-asleep on a shoulder. The older kids ran for the couch and the crayons; the littlest climbed into my lap as if I’d been saving the seat for him his whole life. We set the table with mismatched plates and cloth napkins I’d sewn during a winter I can no longer place by year, only by the way the snow made the windows glow. We ate until the bowls went to clink and clatter and scrape. A cup spilled, hands moved, the moment closed without fuss.

I cut the pie last. Same recipe, same pan, same crimped edge that remembers my fingers. I waited until every plate had a slice before I took mine. Someone slid me the final piece with a grin. “You made it,” she said.

“I did,” I said. “And this seat is mine.”

I meant the chair and the room and the life that held them both.

News trickled in the way it does in towns where once a month you still run into the kindergarten teacher who slipped you graham crackers when your mother was late. Everett’s refinancing collapsed. The deal with Rosa’s family dissolved once the house left the table. Rosa’s parents expected only sure things wearing a suit and tie. Everett had never made stability more fashionable than risk. He changed his phone number. Or maybe he just stopped answering mine.

One afternoon, an envelope arrived without a stamp. Inside was a formal invitation embossed with a gold seal: Eastbrook Single Mothers’ Scholarship Fund—annual luncheon and awards. Below, in ordinary type, a line that knocked breath sideways: Presentation of the first Kalista Moure Legacy Award.

At the banquet, the ballroom smelled like coffee and orchids—expensive and kind at once. I wore the navy dress I kept for weddings and funerals and sat between a nurse who’d gone back to school at forty and a woman who had left a man who didn’t know what promises were for. When they said my name, I stood to a sound I wasn’t used to hearing anymore: applause tilted toward one person’s courage. I didn’t give a speech. I just said thank you and meant it. On the way out, a young girl in patent leather shoes tugged my sleeve. “My mama got the scholarship,” she said. “She says we can stay near our school now.” I knelt to her height. “That’s the best kind of staying,” I said. She nodded like she’d just learned the word for a thing she’d always wanted.

A week later, Everett knocked.

It had been three months. Shame takes its time choosing shoes. He stood on the porch in a wrinkled dress shirt and a tie that looked like a habit, not a choice. He held nothing in his hands. For a second, in the tilt of his head, I saw the boy who used to holler from the driveway, Mom, look! hands stained with marker, knees green with grass, joy he hadn’t learned to measure yet. Then the second passed.

“Can I come in?” he asked.

“This is my home,” I said, and the sentence was a key I’d cut myself. “You can come in if you can sit at my table and speak to me with respect.”

He swallowed. His eyes were red-rimmed, but not from drinking. There are other ways to ruin a body. “I—” He had always been good with words. The right ones didn’t come easy now. “I’m sorry,” he said finally. “Not just for dinner. For… for everything else.”

“For lying,” I said. “For using me. For thinking I was something you could move like a lamp.”

He winced. “Yes.”

I stepped aside. He walked to the dining room and paused as if waiting for someone to assign him a chair. I nodded at the head of the table—the same one he’d saved for Rosa without asking, the same one my husband had taken the night before his diagnosis, the same one Everett had promised to save me when he was eighteen. He didn’t sit there. He chose the side, halfway down. Good.

We didn’t talk about Rosa. We didn’t inventory losses or tally blame like accountants with different ledgers. He told me about the silence that followed his mistakes, the way his phone felt heavier in his pocket each day it didn’t ring. He told me his hands didn’t know what to do without a plan to wave around. He told me he was tired of the sound of his own ambition and the way it always needed someone else’s oxygen.

“I thought I was building a future,” he said. “I was just pawning my present.”

“You thought love was leverage,” I said. “You thought family was collateral.” I said it without bitterness. Truth doesn’t need a blade. It is one.

He nodded. “I can’t ask you to forgive me.”

“You can,” I said. “You just can’t expect me to owe you my yes.”

He pressed his lips together. “What can I do?”

“Learn to be the kind of man who doesn’t need to be forgiven to be good,” I said. “Start there.”

He ate pie at my table. He asked for the recipe. He laughed once, a small sound like a pilot light catching. When he stood to leave, he looked at the porch light overhead. “I meant to fix that,” he said.

“I know,” I said. “I fixed it.”

He nodded, then reached into his pocket and pulled out a key. The brass had the shine of overuse. He placed it on the entry table—the same place Rosa had laid her folder, the same place I’d keep mail and grocery lists and notes from the center.

“I don’t live here,” he said. It wasn’t a question. It was a sentence written on purpose. “I shouldn’t have kept this.”

“Thank you,” I said. I didn’t pick it up.

After he left, I stood in the doorway until the evening settled. The house didn’t feel lighter. It felt right. There’s a difference you can’t explain to anyone who hasn’t felt it.

He called on Sundays after that. Not every Sunday. Some. He told me about work at a warehouse he’d taken because pride doesn’t pay rent. He told me about the way his back learned the honest ache of lifting and stacking. He didn’t tell me about Rosa, and I didn’t ask. Sometimes he brought my granddaughter, whose note was still on my fridge. She watched me make pie and asked if the crimped edge had a trick. “Only practice,” I said. “And hands that don’t rush.”

The scholarship house, as the women at the center called me when they forgot I could hear, became what I wanted it to be. On Tuesdays, we practiced reading leases like stories that might have better endings if we noticed the villains early. On Thursdays, we hosted a pot of something cheap and good—beans with a ham bone when someone donated one, pasta with tomatoes and basil when the garden was in a mood. On Saturdays, the kids dragged blankets onto the living room rug and fell asleep in a heap that reminded me of puppies, all breathing the same gentle rhythm.

On Mother’s Day the following year, I woke to sunlight arranged on my wall like generosity. I brewed strong coffee and set out plates. I didn’t plan to go anywhere. I didn’t expect anything. I didn’t rehearse speeches for guests who might not come.

A knock at the door. Not a push, not the tiptoe of assumption. A knock. I opened it to find three of the women from the center, grinning, with arms full of groceries and a cardboard sign that read YOU ARE INVITED in purple crayon. A step behind them, shy and tall and carrying nothing but himself, was Everett.

“Dinner’s at your table,” one of the women said, laughing. “We thought you might like to be the one who didn’t cook everything for once.”

“You’ll need to supervise the pie,” another said. “We don’t argue with legends.”

I stepped aside. They flowed in. Everett lingered.

“May I?” he asked, gesturing toward the dining room.

“This is my home,” I said. “And I am the one who invites.” I held his eyes for the space of a breath, then added, “Come in, Everett.”

We seated Rosa’s empty ghost nowhere. We put my granddaughter between me and the window where the light makes her hair look like sugar. We filled the table. No one fought for the best chair. No one told me to sit in the kitchen. Everyone made room.

At dessert, I set the pie on the table and handed the knife to the girl with purple crayon on her fingers. “You can cut,” I said.

“I’ll mess it up,” she whispered.

“That’s okay,” I said. “We’ll eat it anyway.”

She made uneven slices. We applauded like she’d performed a symphony. We ate the pie. It tasted like butter and pecans and the kind of salt you can only taste after you’ve cried and slept and woken up better.

Later, after the dishes and the hugs, I walked into the front yard and watched the sky turn the color of forgiveness. The porch light didn’t flicker. The basil was already plotting how to take over the corner. The house hummed with the sound of a dishwasher and a life.

My phone buzzed—a text from an unknown number. It was a photo: my granddaughter’s drawing from that afternoon. Me, a table, a crooked heart, and the words Grandma’s Seat. Below it, Everett’s message: I know now. Love is a chair you build, not one you take. Thank you for letting me earn a place again—someday.

I typed back only: Keep showing up.

I went inside and set one plate at the head of the table, because I can save a place for myself without asking anyone’s permission. I poured one more cup of coffee, sat down, and did the quiet work of living in a house that was mine by law and by labor and by love.

Last year, my son pushed me and said, “That seat’s for my mother-in-law—get out.” So I did. I left that table and set another, one made of paper and clauses and the stubborn wood of a woman who learned you don’t hand your life to anyone who hasn’t earned a place at it.

This is the table I keep. This is the table I share. And this seat—this seat is mine.

The End.

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS. CH2

Father banned me from my own FIVE-STAR HOTEL, So I told SECURITY to REVOKE their VIP ACCESS Part 1…

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call. CH2

Boss Fired Me 3 Days Before My Pension Vested After 29 Years With The Company. I Made A Phone Call….

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant. CH2

My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant, i…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I Was… CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I…

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… CH2

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… …

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner. CH2

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner …

End of content

No more pages to load