MY SON ORDERED ME: OBEY HIS WIFE OR LEAVE I SMILED, TOOK MY SUITCASE, AND WALKED AWAY…

Part I

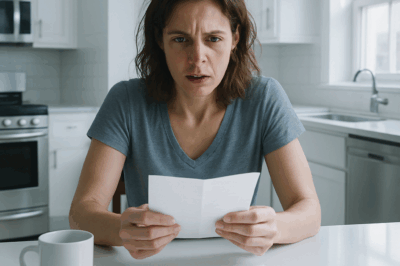

“So that’s your final answer. You won’t cosign.”

Mark’s voice had that tight, tinny whine I’d come to associate with his rare attempts at authority. A wire stretched between us like something a trapeze artist would cross—a wire of entitlement he believed could hold a man twice his age and the weight of a house he’d never paid for.

He stood in my kitchen with his arms folded, chest puffed, chin set high as if the posture alone could make him a provider. Behind him, my daughter Clara traced the gray-and-white veins of the marble island I’d installed for their anniversary. She had picked the stone herself, running her palms across it while a salesman spoke in jargon about Carrara versus Calacatta. I’d told her to choose what she loved. She chose beauty. I paid for both.

“The answer is no, Mark,” I said, steady. My reusable grocery bags sagged by the door, the milk warming, the bananas freckling. “Your boutique coffee-roasting venture is a hobby, not a business plan. The bank sees it, and so do I. I will not secure a $200,000 loan against this house for it.”

He scoffed. “It’s not your house anymore, old man. It’s our house. We live here. We’re building a life here.”

Clara’s eyes flinched at “old man,” but she didn’t correct him. She looked at me, a pleading brightness in her gaze. “Dad, please. It’s important to him—to us.”

“What’s important,” I said, letting my lawyer’s cadence return like muscle memory, “is fiscal responsibility. Something he’s yet to demonstrate.”

I saw it then—the wire snap. Mark’s face mottled with red. He took one step closer, dropped his voice low as if menace were gravitas. “You live under our roof. You follow our rules. Clara is my wife. This is my family. You will either do as you’re told and support us, or you can get out. It’s that simple. Co-sign the loan or pack your things.”

He flicked his eyes toward her, a silent command in the air. I’d seen that small flick before, in depositions when a weak witness looked to counsel for a lifeline. Clara straightened. Her voice was a pale echo. “He’s right, Dad. You have to choose. It’s us… or it’s you.”

There are moments when a life clarifies with the cool efficiency of a contract coming into focus—definitions, terms, a termination clause. The old ache—five years old now since losing Elellaner—quieted. The hum of worry I’d carried for them for so long ceased. I saw the last decade as columns on a spreadsheet: on one side, words like love, duty, grief; on the other, outflows with no return.

I’d paid $412,000 for Clara’s medical school—the loan statements still lived in a file I could retrieve by feel in the dark. I’d paid $78,000 for a country club wedding that looked like a magazine spread and felt like an unpaid balance. I’d given $60,000 for a down payment on a condo they sold at a loss when the HOA fees finally outpaced their optimism. For three years, I’d paid my own mortgage, utilities, and taxes—$3,800 a month—so they could “get on their feet” beneath my roof. That roof I had built with a woman whose name still lived on the underside of the rafters in pencil, written there one summer when we were giddy with paint.

I had been an investor with no prospectus, a bank with no terms. Nothing about that was love; it was negligence dressed as generosity.

“What an elegant contract,” the attorney in me observed, even as the father felt his ribs ache. “Offer. Acceptance. Consideration. Breach.”

I smiled. Not the brittle politeness that had kept us functioning for three years, but the small, precise smile of a man who’s found the clause that will set him free.

“I see,” I said. “That certainly simplifies things.”

I lifted the warm groceries onto the counter—bread, milk, fruit. “You’ll need these.”

Then I walked past them, up the stairs, and into the room with the mahogany bed that had held a marriage, a widowhood, and—more recently—nights of bad sleep interrupted by the rhythm of Mark’s gaming through the floorboards. I packed. Three changes of clothes. Toiletries. The framed photo of Elellaner from my nightstand, her grin halfway to laughter. My laptop. The thick leather folio of account numbers, deeds, wills, insurance policies—the bones of a life I’d kept in order while letting my heart run wild with hope like an untrained dog.

I carried the suitcase down the stairs. They had moved into the living room, their eyes following me like cats watching a bird inside the house. I didn’t offer a speech. Men who talk too much before they leave are asking to be convinced to stay. I set the suitcase in the trunk of the car we all pretended was Clara’s, because I had once believed in fictions that made other people feel grown.

Driving, I waited for grief and felt analysis instead. The neighborhood rolled past like footnotes to the life I’d edited for them: the neighbor who shoveled our walk without asking; the retired cop across the street who pretended not to see when Mark stumbled home at three a.m.; the maple tree whose roots had spidered into the sidewalk like a warning.

I found a motel twenty miles down the interstate. Beige walls, a faint disinfectant smell, a bolt that slid smoothly, a desk that would just fit the laptop. I paid for a week in cash—old habit, not paranoia. I slept like a man who’s finally invoked a clause that was always there.

The morning was for work. My career had trained me to act before feelings had a chance to muddy intention. I opened the folio.

The bank first. I was the sole name on the mortgage. “I’d like to cancel all automatic payments effective immediately,” I told the representative. Authorization codes. Two security questions. Ninety seconds. A soft internal click.

Insurance next. I owned the two cars they drove. “I’m selling a 2022 SUV and a 2021 sedan,” I told my broker. “Remove them from the policy. Remove Clara and Mark as listed drivers.” Jim, who’d known us for years, asked gently if everything was all right. “Everything is becoming all right,” I said. Email confirmation arrived before I hung up.

American Express. Clara had been an authorized user on my Platinum card since her third year of med school; at some point, that privilege had extended to Mark as naturally as mold. “I’m reporting a card lost,” I said, reading the number. “And I want to remove an authorized user permanently.” The customer service agent read from a script that was both apology and relief. Another lock clicked.

My estate lawyer. “Richard, I need to come in and make significant changes to my will and the beneficiaries on my life insurance.”

“How’s tomorrow morning?” he asked. His voice was a harbor.

By day three, the organisms in the petri dish discovered their nutrient supply had been cut off. I let calls roll to voicemail and listened in the quiet with an objectivity that surprised me. Clara’s voice progressed from buoyant problem-solving to plea to panic. Mark’s texts came as single-line commands and then profanities, language I’d heard in courtrooms when men realized their leverage had been imaginary.

On day five, the motel’s sun-bleached curtains cast light like a stage across the bed as their SUV screeched into the lot. Mark hammered on my door. “What the hell is this?” he demanded when I opened it. “You can’t just cut us off. The mortgage is due. The car insurance—what are you playing at?”

“I’m not playing at anything,” I said. “I’m following your instructions. You gave me an ultimatum: support your family under your rules, or get out. I got out. The financial arrangements existed because I lived in the home and chose to subsidize the household. Since I am no longer in the home, the arrangements are concluded.”

Clara’s eyes were red-rimmed. “Daddy, please. This is insane. We didn’t mean for you to actually leave. We were just upset. You know how Mark gets. Come home. We can talk about the loan.”

“There’s nothing to talk about,” I said, and I made myself stand still, the way you learn to in mediation when movement looks like weakness. “You confirmed the terms. You chose ‘us.’ Now you and Mark get to be ‘us.’”

“Respect?” Mark laughed, but it broke in the middle. “You’re an old man living off his pension. We were doing you a favor—letting you stay.”

“Letting me stay?” I let silence do my cross-examination. “Mark, the deed to that house is in my name. The mortgage is in my name. The taxes are paid from my bank. You are, in the legal sense, tenants at sufferance. And your tenancy is over.”

The color in his face drained as if I’d pulled a plug. Clara sobbed, the sound of a person finally hearing the echo of her own choices.

“You can’t do this to your own daughter,” she said. “Where will we go?”

“You’re both adults,” I said, gentler for her than for him. “You’ll figure it out. The way you were so confident you could figure out a boutique roasting business.”

I glanced at my watch. “I have a meeting to get to.” I closed the door on their stunned faces with a click that matched the phone calls I’d made: soft, final, clean.

In the lobby of Richard’s building, I ran into George, an old colleague who’d left our firm to run risk assessment at a major bank. We shook hands. He tilted his head. “Arthur, funny coincidence. Your son-in-law—Mark, right?—came to us last month. Tried to secure a line of credit. Used your property as potential collateral.”

My ribcage went quiet. “I didn’t authorize that.”

“Thought not,” he said. “The paperwork was… creative. A forged power of attorney. We flagged it, denied it, and didn’t file an official report—out of respect for you. But he’s leveraged to the hilt. Heavy online gambling. He’s desperate.”

The coffee business unmasked itself in a breath: not ambition, camouflage. A hole, not a plan. And there it was, too, the long game I should have seen and had only suspected: three years living in my home without paying a dime—a man who knows how adverse possession works and thinks time will hand him what hustle won’t.

Richard slid a folder across his desk, and I put my palm on it like a man swearing in. “We need to file a formal eviction,” I said. “Thirty-day notice to quit. Served by a sheriff’s deputy. I want it official, documented, undeniable.”

“That’s aggressive,” he said mildly.

“His actions were fraudulent and predatory,” I said. “I’m responding proportionally and legally.”

The notice was served two days later. The explosion traveled its usual paths: cousins who forwarded me messages that began, “We’re so worried about Arthur,” as if worry were a hand-shovel that could bury the facts. A teary call to a notorious aunt: “We think I might be pregnant.” The rumor reached me before Clara realized how many people had learned to copy-paste. A baby as a human shield. A pawn, not a person.

They had chosen the court of public opinion. I answered there. When I learned from a neighbor that Mark was holding a “community support barbecue” on my front lawn, grilling meat on the shiny gas contraption I’d bought him last Father’s Day just to keep a truce from collapsing, I drove over. I didn’t walk into the yard. I stood on the sidewalk with a knot of neighbors and greeted Bob—the retired cop across the street—like we were catching up in line at the deli.

“I’m sure you’ve heard Mark’s version,” I said, conversationally loud as he stalked toward us, spatula still in his hand like a prop. “Here’s mine—the one with facts. Two months ago, he attempted to forge my signature on a power of attorney to secure a loan against my house. Not for coffee beans, but to cover over $80,000 in online gambling debts.”

A murmur moved through the crowd. Mark stopped mid-stride.

“Did he tell you my daughter—an M.D.—has not contributed a dollar toward mortgage, taxes, or utilities in three years? Did he mention I’m the sole legal owner of the property he’s currently trespassing on?”

I held up a folded paper. “This is a copy of the eviction notice. This isn’t a family squabble. It’s a legal matter. I gave them a home. They tried to steal it.”

“He’s lying,” Mark sputtered. “He’s confused. He’s—”

“Confused enough to have the bank’s fraud report?” I asked. “Confused enough to have your credit report? Shall we discuss the websites by name? Or should we skip to your plan to assert adverse possession in four more years?”

He shut his mouth. You can’t outrun verifiable facts; they’re faster than shame.

People looked from me to him, back again. I saw sympathy turn, like a school of fish suddenly deciding all at once to swim in a different direction. Mark retreated, screen door slamming. The barbecue deflated like a raft with a slow leak.

That night, my motel landline rang. No one had that number. “You think you’re so smart,” he hissed. “Old men have accidents. Old men fall.”

I didn’t dignify it with 911. I called Bob. “Get a restraining order,” he said. “And be careful.” He also offered everything neighbors offer when they’re who they say they are: his son’s name on the force, a promise to keep eyes open, and a piece of news—there’d been shouting at the house. A wellness check. Clara was seen packing a bag.

The affidavit from the bank, the threat on the phone, and my age earned me a temporary restraining order. Mark was now legally barred from coming within five hundred feet of me or my residence—motel rooms count. The sheriff who served it had the same calm in his voice as the nurses who had spoken to me after Elellaner died: firm, practiced, a little tired. “Call if he breathes wrong in your direction,” he said.

The eviction date arrived. They weren’t out. The sheriff was. The law moved on its slow, heavy feet; it moved enough. Mark and Clara left with boxes in the back of Clara’s compact. The SUV I’d been paying for was repossessed two weeks later. When the restraining order made Mark’s temper too expensive, employers and creditors began to take notice. Losing access to my name is a solvent; it dissolves the residue of a man like him fast.

Then Clara called me. Not from the number I knew. A pay-as-you-go line. Her voice was ruined by crying, but quieter, a hollowing I recognized from my own first year without her mother.

“I left him,” she said. “He ran. The pregnancy was a lie. I let him talk me into… everything. I was wrong. I was weak. I chose him over you.”

I listened until she ran out of words. You learn, in grief groups, to save advice for later. When she fell silent, I held my silence a moment longer. Then I told her my terms—the most difficult contract I’ve ever drafted.

“You betrayed me publicly,” I said. “With family. With neighbors. Your apology must be equally public. You will write a letter to the editor of the local paper. You will post a full and honest accounting of your actions on your social media. You will stand in front of our church congregation and tell the truth—what Mark did, what you allowed, what lies you told. You will spare no detail. You will take full responsibility.”

She breathed into the phone like a swimmer who has come up too far from shore. “And if I do all that,” she asked, small, “can I come home?”

“No,” I said, gently. “The home is the poison. It represents money and entitlement—what he wanted, what you were willing to sacrifice me for. I’m taking it off the table. I will donate the house, fully paid off, to a foundation that provides housing for wounded veterans. It will be called ‘Elellaner’s House.’”

She made a sound I couldn’t name—grief and relief and something like awe. She didn’t argue. Somewhere under the wreckage, the daughter I’d raised could read a clean clause when she heard one.

“I want a relationship with my daughter,” I said. “But I will not have a dependent. If you do this—if you reclaim your integrity publicly—we can talk about what a new beginning looks like. The choice is yours.”

Two Sundays later, I sat in the back pew of the small church where we’d dedicated Clara as a baby, where the casseroles had been stacked high when we buried her mother, where I had stood alone so often the past five years and tried to convince God to learn contracts. Clara walked to the lectern. She looked thinner, older. She put her hands on either side of the wood and she told the truth.

She did not embellish. She did not blame fatigue, hormones, or stress. She named the theft in her own heart before she named Mark’s. She confessed the lie about a child. She apologized to me without asking me to absolve her, to the congregation without asking them to co-sign.

People stared, then looked down. Some shook their heads. Some nodded once and folded their hands like men waiting for the verdict in a small-town trial. When she finished, she walked out without looking left or right. No one followed her. A good confession is not a performance; it’s a demolition.

Part II

Mark vanished the way men who are ashamed and addicted do: overnight and into a version of America where there is always another couch, another online account, another lie that works until it doesn’t. The sheriff’s office filed a report when we didn’t know his address. The restraining order sat on a clipboard labeled “Pending.” I slept well for the first time in months.

I signed the donation papers for the house and watched the deed transfer under my hand. The director of the foundation—a woman whose brother had been wounded in a war I had signed petitions against—walked through the rooms with the reverence of a person being granted stewardship. “We’ll name it after your wife,” she said. “Elellaner’s House.” She tested the name in her mouth and smiled. The place began to lift in my imagination, as if the ghosts of entitlement were leaving through the eaves.

Neighbors watched moving trucks bring in beds that were needed, cribs that would be used, a ramp for a front step that had been an annoyance to Mark and a barrier to the men now carrying a new life over it. There should be a word for what it feels like to see a space that betrayed you made holy by helping someone else. I don’t know that word. I know the feeling.

I found a small apartment overlooking a park. It had generous morning light and a kitchen that would not tolerate a dinner for ten, which is to say it fit me exactly. I kept books and the framed photograph and the folio. I let go of the rest with the calm of a man who has decided he will no longer inventory what was taken and will instead count what he has.

Richard and I rewrote my will. We adjusted beneficiaries. We set up a scholarship fund in Elellaner’s name at the clinic where she had volunteered, a place where nurses spoke in the tone that saves lives and fixes grief with coffee and good sense. We inserted clauses that would make it impossible for any future Mark to try what this one had. We created a trust that required service, not sentimentality, to receive anything from me.

The calls from family slowed, then stopped. The aunts found new gossip. The cousins discovered a sale. People want scandal to be simple. Mine wasn’t. That makes it boring to anyone who isn’t living it.

Clara took a job across the country, in a clinic that served people who don’t get press releases when their lives get better. She sent me letters. Not texts. Not emails. Letters written by hand in a script that had always leaned a little to the right, as if it were eager to arrive. The first ones apologized again—different words on different paper, griefs cataloged like receipts. I read them and did not reply. Contrition has to exhaust itself before you can begin.

Then her letters changed. She wrote about a patient who’d arrived with a blood pressure that would have frightened a stone, and how they sat together in a tiny room while Clara explained salt like it was a miracle and the woman laughed until they both cried. She wrote about a boy who learned to breathe into a paper bag and then taught his mother how to do it. She wrote about loneliness in a town where the sky was so big you could stop pretending you mattered to the stars.

“I finally understand,” she wrote, months later, on a night when the postmark said snow. “You didn’t just teach Mark a lesson. You taught me one. Respect isn’t given. Dignity isn’t inherited. They’re built, day by day. Thank you for making me start my own construction.”

I folded that one carefully and slipped it inside the journal where I’d written the totals that first night, the numbers of a life I’d miscounted until I stopped pretending math was heartless. Numbers don’t lie. Love shouldn’t either.

We did not see each other. Not at first. People imagine reunion as a movie scene: running, tears, the camera spinning. For some, maybe. For us, the new relationship was going to be a bridge we built from both ends, plank by plank, wave by wave. Connections that had been strained by money and myths needed weight-bearing tests: ordinary phone calls; a photograph of a sunset texting me at 6:03 a.m.; a recipe for the soup her mother had made when colds ran through the house like rumors. We started there.

One morning, a picture came through: three children on the porch of Elellaner’s House, coloring while their parents fixed a squeaky bedroom door. The ramp gleamed. Someone had planted a garden with more hope than horticulture. “I thought you’d want to see,” the director texted. I sat at my little table and cried with my napkin, not my sleeve, the way my wife had insisted. “You are still a person,” she’d say when grief made me sloppy. “Act like it.” So I did.

On a Wednesday, the restraining order hearing was scheduled to become permanent. Mark didn’t show. The judge looked over his glasses at me and frowned gently as if to say, “I see you. I’m sorry.” The order became a stack of papers, stapled. I put it in the folio with the deed donation and the scholarship paperwork. The folio was looking less like a record of my life and more like a map.

Bob knocked on my door one afternoon with a small cardboard box. “Found this between the hedges,” he said. “Old mail.” Inside were postcards I’d forgotten—I’d sent them to myself during a trip with Elellaner to places we could pronounce with more enthusiasm than accuracy. “Wish you were here,” I’d written to a future version of me who’d needed reminders that I had been happy. I stuck them to the fridge like a teenager.

Grief has a way of quieting you into attention. I noticed the park more: the woman who jogged with knees that argued; the man who sat every morning on the same bench, counted to one hundred under his breath, and then stood; the teenagers who practiced a dance routine badly and then better and then grinning. I bought a notebook not for legal notes, not for budgets, but for a list of things I had learned too late. At the top: People who love you do not make you trade your dignity for their comfort.

I saw Clara one year after the eviction. We planned it like an operation—public place, daylit, a table between us. She walked in wearing scrubs that had lost their starch and found their purpose. We hugged like careful carpenters, measuring twice. We talked about nothing as if it were a lavish meal. When the check came, we argued about it, because arguing about the check is how families confess they are trying.

“Come see the clinic,” she said, tentative, later. I did. I watched her put her hand on a patient’s shoulder and explain a pathology in plain language. I watched a woman cry and then laugh and then cry again. I watched my daughter be a doctor, not a dependent. In the parking lot, under a sky that looked like it had been ironed, I said, “I’m proud.” The words felt like weather. Not necessary to breathe, but good to notice.

We visited Elellaner’s grave. We brought flowers that she would have declared gaudy and then arranged anyway. We stood there and said nothing, because what is there to say? Love is a contract you honor when your partner can no longer sign.

Sometimes guilt tried to come back, like smoke through a vent you thought you’d sealed. “You could have stayed,” it said. “You could have spared her all that public shame.” I answered it the way I answer a clause that pretends to mean something and doesn’t: “Then I’d still be in that house, paying for lies. And she’d still be there, living them.” The smoke dissipated.

The veterans’ kids learned to ride tricycles on the driveway. The roses revived. The neighbors started using the name without stumbling—“You coming over to the cookout at Elellaner’s House?”—and it fit like shoes that had finally been broken in. Once, a little boy dropped a can of paint on the ramp and we all laughed and then cleaned it and then laughed again because the white smear made the ramp look like it had survived a storm. Which it had.

Mark never resurfaced in any way that mattered to me. A creditor called once and asked if I had a forwarding address. “No,” I said, then added—which felt like laying a brick right where it needed to go—“and he is not my problem.” I hung up and wrote it down in the notebook: You can decide who is not your problem.

Part III

On the second anniversary of my leaving, I hosted dinner for the director of the foundation and the three families living at Elellaner’s House. We ate outdoors on borrowed tables. Children ran fast and fell and cried and then were fine. Someone brought potato salad that could win a war. I grilled with the kind of focus that makes men feel useful. When the sun dropped behind the maple, a man missing half a leg told a story about a medic who had kept him alive by yelling at him for an hour. We all laughed the way people laugh when they recognize a tone.

In the quiet after, I thought about the kitchen where Mark had tried to make me choose. I thought about the word “family” as if it were a contract that had needed amendment. I thought about love as equity, about duty as due diligence. The metaphors should have made me tired. They didn’t. They felt like the correct shape of things.

Clara called that night. “How was it?” she asked.

“Messy and perfect,” I said. “Like most good things.”

“I got offered a permanent position,” she said. “They want me to run a program for teen mental health.”

“Then do it,” I said, and heard myself sound like a father whose love has nothing to do with money.

“Dad?” she said, softer. “Can I ask something… impractical?”

“Of course.”

“Will you come to church with me next month? Not to make a point. Just… because.”

I did. We sat in the back again because that’s where people sit when they’ve learned to be humble without forgetting their names. The pastor preached about Zacchaeus, the tax collector who climbed up into a tree for a better view of Jesus and then climbed down when called. I thought about climbing, about descending, about the honesty of height. We took communion. Bread. Cup. Old bones of faith.

Afterward, a woman I hadn’t seen in years came up to me. She had been part of the choir during the worst of it. She looked at me with the specific tenderness of someone who’d once believed the wrong narrative and then learned to be embarrassed about it. “I’m sorry,” she said, and I believed her. I didn’t say, “It’s fine.” I said, “Thank you.” We stood in a small silence that felt like healing.

On a Tuesday afternoon, I got an envelope in the mail with the crest of the state on it. Inside, a letter informed me that the restraining order had expired and there’d been no contact. “Do you wish to renew?” it asked. I held the paper and felt nothing—no fear, no petty desire to keep the paper just to prove a point. I didn’t renew. Not because I trusted Mark or the future, but because some contracts serve their purpose and then, like scaffolding, can be taken down.

I added another page to my notebook: “A boundary is not a wall; it is a door with a lock and a key you are allowed to keep.”

Clara’s letters tapered into phone calls, which tapered into something that looked—if you squinted—like a routine. We didn’t resurrect the old intimacy. We made a new one. Sometimes she called to ask about a recipe and then cooked it badly and sent me a photo anyway. Sometimes I called to tell her about a book and she ordered it and we read it simultaneously and then set a time to argue about the ending as if we were in a club. We were. It had two members. That was enough.

A boy at the clinic asked Clara if she had a dad. “Yes,” she said. “He’s stubborn and he makes good soup.” The boy laughed and said, “So… like a dad.” When she told me, I wrote another line in the notebook: Sometimes redemption is a joke made by a child you’ll never meet.

On a morning when the park was full of dogs and men who admired them, I took the folio out and replaced the old will with the new one. I held the paper and thought of all the contracts I had drafted, negotiated, enforced. So many clauses. So many signatures. The best one, I decided, had been the simplest: I smiled, took a suitcase, and walked away. I wish I could tell my younger self that “no” is a complete sentence, that “leave” is an act of love when staying is a kind of theft—from the self, from the future.

Part IV

If there is a final act, it is not epic. It is quiet, made of small things done consistently. I wake early. I make coffee that would offend Mark’s imaginary customers and delight me. I walk. I cook for people who need to be cooked for. I answer letters with letters, texts with texts, silence with the kind of waiting that is not a threat.

Elellaner’s House had its first wedding in the backyard: two people who had met in a VA support group and learned to believe that statistics don’t always get to write the ending. The girl wore a dress she’d bought on the internet for forty dollars and the boy wore his uniform because he said he wanted to look like himself. I stood with the rest of the neighborhood and cried like a man who has been allowed to live to see a reversal. I heard someone say the name on the banner attached to the fence and it sounded like a blessing.

Clara visited for Thanksgiving. We cooked in my miniature kitchen like criminals. We burned the rolls and called it rustic. We ate on plates I’d bought at a thrift store because I didn’t trust myself with my old china yet. After pie, she went to the bookshelf and took down the photo of her mother without asking permission because she didn’t need to. “I think she’d approve,” Clara said. “Of all of it.”

“She always wanted you to be brave,” I said. “She never said brave meant obedient.”

Clara looked at me, and the girl who had once traced marble veins with a nervous finger turned into a woman who could meet a gaze and not look away. “Thank you for leaving,” she said. “I hate what it took. But thank you.”

Later, I walked her to her car. We hugged in the crisp air and said goodbye the way people do who plan to see each other again soon. When I came back upstairs, I stood for a long time in the doorway and realized the room felt like it belonged to me more than it had in ten years.

A week after Christmas, a postcard arrived from a place with mesas and sky. Clara had found a tourist shop that still sold them. On the back, in her slanted print, she wrote, “Dad, a kid told me today, ‘Grown-ups are only good when they admit when they’re bad.’ You did that. I’m trying, too.”

I put the card on the fridge next to the old ones I had mailed to myself. The collection looked like evidence—of travel, yes, but more of return.

Sometimes, walking past the old block, I slow down and look without stopping. The house is louder now in the right ways: children arguing over turns, laughter, a door slamming with the abandon of people who are not afraid they’re slamming an ego. The roses are pruned almost comically well. A flag hangs, not because anyone thinks patriotism is a performance, but because someone inside earned the right to hang it without explanation.

I am not a saint, and this is not a sermon. There are nights when I still feel the tug of the years I lost—to grief, to hoping, to funding the lie that love and money are synonyms. But the tug grows weaker each year. And when it comes, I answer it with action: I send a check to the clinic. I take soup to a neighbor. I write to a friend who is in the middle of a leaving and does not yet know that the first step also counts as progress.

When people ask why I gave away the house, I shrug. They expect sacrificial language. I tell them the simpler truth: it wasn’t mine anymore. Not the way that mattered. I needed to live somewhere that couldn’t be stolen either by law or by love misapplied. The apartment suits me. It holds a chair that fits my back and a lamp that flatters my books. The window shows me a slice of the world that is manageable and beautiful.

If you are looking for a grand declaration, here it is: I loved my daughter more than I loved being needed. I loved my wife more than I loved our furniture. I loved my integrity more than I loved my role in other people’s stories. These are decisions you make one morning when you put grocery bags on the counter and decide the milk can spoil if it has to. You invoke the termination clause. You sign here. You date there. You close the folio. You walk away.

And then—this is the part people don’t tell you—you don’t spend the rest of your life walking. You stop. You turn. You build.

On a spring afternoon, sitting on my bench in the park, a child on a scooter barrels toward me, wobbles, and pulls up just short. “Sorry!” he shouts, fearless and sincere. His father jogs after him, winded and smiling. “We’re working on the brake,” he says.

“Aren’t we all,” I reply.

On the way home, I buy a loaf of bread and a bottle of decent wine and two apples that taste like September no matter the month. I climb the stairs that are exactly the number my knees still tolerate. I unlock my door. My small place receives me with the gentle indifference that means safety. I set the bread down. I open the journal where Clara had written, months ago, the sentence that undid me: Respect isn’t given. Dignity isn’t inherited. You build them, daily.

I add one line beneath it: And when someone orders you to trade them away, you smile, take your suitcase, and walk toward the life big enough for both.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

After Three Years of Silence, I Received a Letter from My Dad. But When I Looked Closer…

After three years of silence, I finally received a letter from my dad. At first, I thought it was the…

Mom Said We’re Doing Thanksgiving With Just The Well-Behaved Kids Yours Can Skip This Year.My Child

Mom Said, “We’re Doing Thanksgiving With Just The Well-Behaved Kids — Yours Can Skip This Year.” My Daughter Started Crying….

My Parents Chose Dinner With My Brother’s Girlfriend Over My Life — Then My Letter …

My Parents Chose Dinner With My Brother’s Girlfriend Over My Life — Then My Letter … Imagine lying in a…

My Parents Laughed When I Walked Alone To My Wedding, But Their Faces Changed When The Doors Opened

My Parents Laughed When I Walked Alone To My Wedding, But Their Faces Changed When The Doors Opened. My Parents…

On My 30th Birthday, My Parents Withdrew $2.3 Million That I Saved – But They Fell Into My TRAP

On My 30th Birthday, My Parents Withdrew $2.3 Million That I Saved – But They Fell Into My TRAP My…

My Nephew Mouthed, “Trash Belongs Outside.” Everyone Smirked. I Nodded, Took My Son’s Hand, and Left

My Nephew Mouthed, “Trash Belongs Outside.” Everyone Smirked. I Nodded, Took My Son’s Hand, and Left Part I Sunday…

End of content

No more pages to load