My son beat me up just because the soup wasn’t salted. The next morning he said “my wife is coming for lunch, cover everything up and smile!” then he went to the office and when he entered his boss’s room, he turned as pale as chalk…

Part One

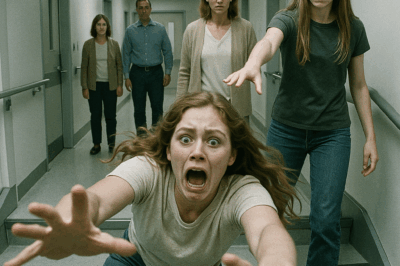

My name is Monica, I’m sixty-one, and last night my only son hit me until I bled over a bowl of unsalted soup.

I didn’t cry then. Not because it didn’t hurt—my cheek burned, my lip split, and a hot slick of broth and shame ran down my neck—but because there’s a kind of crying that takes place in the bones and makes no sound. I cleaned the floor, collected the porcelain shards like I was gathering pieces of myself, and went to bed with a towel against my mouth so I wouldn’t stain the pillow he despises when I “make things messy.”

This morning I woke stiff, the bruises blossoming like violets under my thin skin. Ethan sat at the kitchen table already dressed, scrolling his phone with the indifference of a man who believes the world exists to meet his needs. He didn’t look up when I came in.

“Breakfast,” he said. “I have an important meeting.”

I made his eggs exactly as he likes them. Three spoonfuls of shredded cheese folded in at the end, two slices of toast—one slightly darker because he says it “releases the aroma”—and black coffee, no sugar. He ate without speaking. When the front door opened, Savannah swept in on a cloud of perfume and sunlight.

“Good morning, Mrs. Davis,” she sang. She calls me that when Ethan is around. When he isn’t, she acts like I am an appliance. She kissed his cheek, slid into a chair, and asked for a “light coffee, artificial sweetener, please,” like a queen playing at humility. If she noticed my swollen lip under the makeup Ethan had wordlessly handed me, she said nothing. Her eyes flicked over me, then away, as if she’d glanced into a cupboard.

“Mom,” Ethan said, loud enough for Savannah to hear. “I bought you that foundation to cover those little scrapes from last night. Be more careful when you walk.”

He smiled when he said it. A polite smile, the one he uses at parties, the one that never touches his eyes. My son can lie like breathing.

After breakfast, he adjusted his red tie and leaned near my ear while Savannah reapplied her lipstick in her phone’s camera.

“Remember what we talked about,” he murmured. “Savannah’s bringing friends to lunch. Cover everything up and smile.”

“I understand,” I said.

He kissed the top of my head as if he were generous, as if he hadn’t threatened to throw me out of my own house if I ever opened my mouth. Then he and Savannah left holding hands, the perfect couple, leaving behind the faint peppermint of his toothpaste and the severe hush of a house pretending to be a home.

The quiet almost undid me. I sat at the table and let the rage settle the way oil separates from broth. If I stayed still, I thought, perhaps it wouldn’t burn. But rage doesn’t settle; it searches for edges.

The life that led me to this kitchen began three years earlier when Ethan appeared on my doorstep with a suitcase and a story. “The divorce cleaned me out,” he said. “Just until I get back on my feet.”

I had been a secretary for forty years—Sullivan & Associates, downtown, fourth floor. I could type ninety words per minute on a clattering IBM, later on keyboards that felt like spring water under my fingertips. I organized men who thought they organized the world. When Ethan asked to move in, I saw not a man in his thirties who had never paid a bill on time but the little boy whose father left us when he was eight, the boy I bought designer sneakers for because the cool kids had them, the boy I stayed up with past midnight when he was sick. I opened my door. I didn’t know I was opening a cage.

At first, he cleaned his plate and said “thanks.” He took out the trash without a sigh. He left his shoes by the door like a promise. Then came the comments. The food is too salty. The bathroom’s not clean enough. Your clothes are wrinkled; it’s embarrassing. He offered to “help” with my pension because “at your age, Mom, the internet’s full of scams.” I let him. The auto-deposit switched from my account to his. He gave me twenty dollars a week for “incidentals” and told me not to “waste” it on brand cereal when store brands were fine. When I asked him about the rest, he said he was investing it. “I’ll make it grow for you.”

Then came Savannah. Younger than Ethan by twenty-five years, all gloss and angles and the kind of ambition you can hear in heels on tile. She worked in his office in marketing. Within six months, they were married in a glass-walled restaurant where the waiters pronounced the wine like poetry. He paid for it with my money. I know because he told me I should be grateful to be part of something beautiful.

After the wedding, the pushes turned into pinches and the pinches into slaps. Always in the places covered by clothing at first. “You make me crazy,” he would say afterwards, calmly, as if diagnosing me. “You move too slow; you make me late.” Last night he threw scalding soup. When he sleeps, he makes little growls in his throat like a boy having a nightmare. My heart betrays me and wants to cover him with a blanket.

At ten that morning, as I scrubbed the wine glasses Savannah likes because “they ring when you touch them,” my phone rang. A number I didn’t know.

“Mrs. Davis?” a man said. “This is Adrian Castillo, general accountant for Northern Business Corporation. Could you come to the office this afternoon? There are some… discrepancies… we need to discuss regarding your bank account.”

“My… bank account?” My hand went cold around the phone. Ethan has my account. All of it.

“I’d prefer not to discuss the details over the phone,” he said. “Three o’clock?”

I glanced at the clock. It was half past eleven. Savannah’s lunch would start at noon. There was shrimp to thaw, a salad to dress, tiramisu to unmold. I said yes anyway. Fear and hunger sound the same when they growl.

The bell rang. Savannah and three women swept in smelling like expensive soap. “This is Beatrice from HR, Brenda from marketing, and Evelyn from legal,” she said. “Isn’t it funny that we all work at the same company? Small world!”

When I looked at Evelyn, the room tilted of its own accord. I hadn’t seen my younger sister in two years. She was the calm kind of beautiful that comes from not needing to be looked at to believe you exist. Her eyes widened a fraction; then she smiled the professional smile of a woman who knows how to act in a room full of men and ghosts.

“It’s a pleasure to meet you, Mrs. Davis,” she said politely, and then, under her breath when she hugged me in the hall on the way to the kitchen, “I’ll see you soon.”

We ate. They praised the pasta. Savannah complimented my salad the way one compliments a machine. When I went to the kitchen to retrieve the tiramisu, Evelyn followed with an empty water glass.

“Do you need help?” she said out loud. Then, whispering, “Do you want help?”

“I’m fine,” I lied.

I wasn’t.

Ethan came home early in a good suit, the one he wears on days he expects applause. He pressed his fingers into my shoulder when he said nice things about me. His hands are so clever. They can signal affection and bruise through a blouse in the same instant.

When the door closed behind Savannah’s friends, we cleaned dishes together, which is to say I cleaned and he dried the one wineglass he likes as if that were a favor. “You did well,” he said. “For once.”

At two forty-five, I took a bus downtown to Northern Business Corporation. The lobby was all glass and confidence. The receptionist told me to have a seat. I chose the chair closest to the wall. Old secretaries know to keep their back covered.

Adrian was in his fifties with gray at his temples and eyes that had seen numbers lie and tell the truth. He showed me a neat folder of transfers. Company funds moved to Ethan’s account. From there, to my account. From there, cash withdrawals at the ATM near my house.

“I didn’t know,” I said. “He manages my bank account. He gives me twenty dollars a week.”

“I know,” Adrian said gently. “We didn’t call you to accuse you. We called you to protect you. But we need a formal complaint to clear your name. The company will cooperate fully.”

By the time I left, the afternoon light was going gold on the glass buildings. I walked home slowly. It is astonishing how long you can live in fear and still be surprised by it.

Ethan was waiting at the door. “Where were you?” he demanded. He likes to pretend it is about logistics. It is always about control.

“At your office,” I said.

The moment the words were out, I saw something I had not seen since he was eight and asked why his father wasn’t coming to the school play. Fear. Just a flicker. Then the mask clicked into place.

“You stupid old woman,” he said softly. “You don’t know what you’ve done.”

He raised his hand. The bell rang again.

It was Clarice, my neighbor, holding a casserole. The woman has made casseroles her entire life and knows that love can disguise itself as beef and noodles. Behind her was my sister, hair up, no makeup, the uniform of a soldier on leave.

“We thought you might want something warm,” Clarice said, loud enough for whoever was listening to hear. Then, softly in my ear, “I put a camera in the bushes. It caught him last night. Everything. Come to my house later. We’ll watch the thing together.”

Ethan smiled his public smile. “Isn’t that sweet,” he said, and then, when the door was closed, “Tomorrow we’re going to the bank. You’re going to fix what you broke. You’re going to tell Adrian you authorized everything. And you’re going to put on that makeup I bought and smile while you do it.”

“I’m not going,” I said.

He stared at me like I was a mosquito he had never before considered swatting. For a moment, I thought he might laugh. He didn’t. He leaned so close I could count the pores on his nose. “We’ll see,” he said.

I didn’t sleep. At dawn, I made coffee, not for him but because I needed something to hold. At eight thirty, Clarice knocked at the back door. “The DA’s office,” she said. “Now. My friend Brenda is waiting. And—” She raised her eyebrows. “Bring your phone. The one with the voicemails he left you. And the makeup. You don’t need it, but bring it anyway. I’m funny that way.”

Brenda looked like every attorney who has ever had to argue with a man in a good suit about right and wrong: pressed blouse, sensible shoes, eyes that measured rooms. She listened to Clarice’s recording. She read the transfers Adrian had given me. She asked me, “Are you ready to file a complaint? Today?”

“Yes,” I said, and there was no air left for fear because all the space inside me was taken up by decision.

At ten thirty, a patrol car rolled up to my house just as Ethan pulled into the driveway. I watched it on the DA’s office TV. There is a special mercy in watching your son be arrested from two miles away. You can cry without anyone needing to be brave for. They took him out in cuffs. He shouted my name. The officer, a woman with a ponytail and a look of practiced neutrality that reminded me of myself at thirty, guided him gently but firmly into the back of the car. His face, when the neighbor across the street raised her phone, went the color of old chalk.

“Book him on domestic assault, witness intimidation, and corporate fraud,” Brenda told the arresting officer on the phone. “No bail recommendation.”

I went home that afternoon with Clarice and Brenda. The house looked like a storm had thrown a tantrum. Cushions gutted, picture frames smashed, the portrait of me and Ethan at his high school graduation face-down on the rug with a boot print across it. Brenda took photographs for evidence.

My voicemail had five messages from the jail. They all started with “Mom.” I listened to one. He cried. I did not. That is something we don’t say about violence: sometimes it doesn’t end when they are handcuffed; it ends when you decide not to pick up.

The next morning, I put on my gray dress and went to the courthouse for the bail hearing. Ethan sat at the defense table in orange. He looked at me, then past me, as if there might be a son-shaped door in the wall he could walk through. He promised the judge he was a “respectable citizen” and “a good employee” and that this was “a family matter blown out of proportion.” The judge listened to Clarice’s recording and Adrian’s transfer list and my testimony. Then he denied bail.

“Mr. Davis,” the judge said, “your mother is not your housekeeper. She is not your bank. She is not your property. You are a danger to her and to the integrity of the judicial process.”

Savannah was in the back row, hair immaculate, eyes red. After court, she approached me in the hallway. “Mrs. Davis,” she said. “I’m—” She swallowed. “I’m so sorry. He took money from me too. I’m filing for divorce. If you need me to testify, I will.”

I nodded. When we shook hands, I felt the tiniest tremor pass from her to me—as if she were returning, without knowing it, the piece of fear she’d taken from me every time she had looked away.

At home, I slept on Clarice’s couch the way a person sleeps after fire. The embers inside me hissed but did not burn.

In the morning, I woke ready to become someone I hadn’t permitted myself to be in years.

On Mondays at Sullivan & Associates, Mr. Sullivan used to say, “Confession is the first draft of defense.” He meant it as a joke about witnesses. I think about it now as a survival strategy.

Two days after the bail hearing, another letter came from the jail. This time Ethan threatened to expose mistakes I’d made at the firm fifteen years earlier—alterations to document packets I’d made at a partner’s direction, a few cash “holiday gifts” I’d never reported because I thought of them as thank-yous. He called it “evidence.” He called me a “criminal.”

Brenda read the letter. “He’s trying to drag you back into his control,” she said. “The legal risk is real. So is the psychological trap.”

“What do I do?” I asked.

“You tell the truth before he does,” she said. “On your terms.”

At two o’clock the next afternoon, I sat in front of a row of cameras at the municipal press room and said my name and my age and the fact that for three years my son abused me. I said: “I also made mistakes in my forties at a firm whose lawyers should have known better than to ask a secretary to do what I was asked to do. I did not know then how serious it was; I know now. I will cooperate fully with any inquiry. My son has been using those mistakes to blackmail me. That ends today.”

It is a scary thing to take off your own armor in public. It is also a way of learning you can still stand without it.

That night, the DA’s office announced they were not pursuing charges against me. “Her voluntary disclosure and cooperation are powerful mitigating factors,” the statement said. “We will focus our resources on the violent offender.”

The next morning, a man in a charcoal suit and kind eyes came to see me at Brenda’s office. “I’m Rafael Miller,” he said, holding out his hand. “I run Northern Business Corporation.”

“I’m not in trouble, am I?” I blurted out, stupid with the habit of fear.

He laughed softly. “No, ma’am. I’m here to apologize. Ethan’s thefts started two years ago. That’s on me. And I’m here to ask: would you consider helping us rebuild the systems he broke? Your references from Sullivan & Associates are stellar. My HR director nearly fell over when she saw your name. We’d be honored to have you.”

I stared at him. “You’re offering me a job?”

“A real one,” he said. “With real pay. And benefits. And respect.”

I’m sixty-one. We aren’t supposed to start over at sixty-one. And yet.

“You should know,” he added, as if he wanted to make me laugh (he did), “your son marched into my office this morning in cuffs for a pretrial meeting, saw me sitting with Adrian and the DA, turned as pale as chalk, and nearly sat on the floor.”

I pictured it. My son, who thinks rooms are made of mirrors, faced finally with a window.

I smiled for the first time in a long time, not the smile of a woman saying “I’m fine” when she is not, but the smile of a woman pulling breath deep into lungs that had been tight for too long.

“Director Miller,” I said, “I accept.”

“Rafael,” he corrected gently. “And welcome.”

Savannah filed for divorce that week. She sent me a letter—three polite paragraphs and a scripture verse I had to look up. She said: “I will testify, if you want me to. I am ashamed I did not do more sooner. I am ashamed I did not do anything at all.” I wrote back and told her shame is a useful tool only if it builds something.

For the first time in three years, I slept in my own bed. Clarice stayed in the guest room with a novel and a mug of tea and a baseball bat. We laughed when she showed it to me, then we both cried a little because women keep each other alive all the time in ways nobody writes down.

I thought that might be the end of the story. I was wrong. It was only the end of the part where I didn’t know my strength.

Part Two

Ethan’s trial date was set for early autumn. Summer unspooled itself in the small ways that make a life: I learned the bus route to my job at Northern. Adrian insisted on showing me the cafeterias that had the good coffee. The young analysts learned to bring their documents to me with tabs and post-its because I have no patience for piles that pretend to be organized. Once, Rafael left a sticky note on my desk that said simply, “We are lucky you said yes.”

At home, I changed the locks. I painted the kitchen. I took down the heavy curtains Ethan said kept the sun out of his eyes and put up white ones that move when the window is open. The first time the light moved across the floor and there was nobody telling me it was “too bright,” I sat on the tile and cried. Clarice sat with me and handed me a dish towel that smelled like lemon cleaner and cinnamon, which is to say, like safety.

The DA’s office called to say that Savannah had given a deposition that could have been taught in law school: precise, remorseful, unflinching. She handed over receipts, text messages, dumb love notes from Ethan that made my stomach twist and my head shake at how charming abusers can be when they want to sound like poets.

Two weeks before trial, Brenda received a call that made her eyebrows climb. “You’re not going to believe this,” she told me. “Your sister wants to talk to the DA as a witness.”

“Evelyn?”

“She works in legal at Northern,” Brenda said. “She was in the lunch crowd the day you served shrimp pasta. Fast reflexes, that one. She’s kept her distance because she didn’t want to tip Ethan off, but she’s been working behind the scenes with Rafael for months. She’ll testify about his forged reports and confidential data leaks.”

That image from my kitchen—the way Evelyn’s eyes had held mine for a split second while she said, “It was lovely to meet you, Mrs. Davis”—reddened and spread into something new: respect layered over the old tenderness that being sisters can survive nearly anything.

The day before trial, I went to the DA’s office to rehearse. Clarice came and ate my peanut butter crackers when I was too nervous to swallow. In the hallway, I saw Savannah sitting on a bench with her bolt-upright posture. She stood when she saw me, then sat, then stood again and finally just walked over and took my hands.

“Thank you,” she said, her voice rough. “I know I don’t deserve it, but thank you for not being cruel.”

“I’m too tired to be cruel,” I said. “Tired and busy. That’s what gets us through.”

The trial itself felt like living inside a documentary narrated by a woman with a voice you trust. I sat behind Brenda. Ethan was there in a suit that fought with his orange jumpsuit for attention. He looked thinner. Part of me wanted to pull a blanket over his knees. That part of me is stubborn. It is also not in charge anymore.

The prosecutor called Adrian first. He walked the jury through charts that made even my old secretary’s eyes water. Then they called me. I told the jury about the soup and the slap and the nights I slept with a towel against my mouth so I wouldn’t stain the pillow he says I am lucky to use. I told them the foundation shade number, because humiliation attaches itself to details, and sometimes details can set you free.

The defense attorney tried to push me into the corner he’d decided I belonged in. “Isn’t it true,” he said, “that you once altered evidence in a court case?” He said it with triumph, like someone revealing a family heirloom that proves he is the rightful owner.

“Yes,” I said. The jurors flinched. Nobody expects confession. “And I confessed that mistake before my son could use it to hurt me further. The DA decided not to prosecute. I’m not proud of it. But I am proud that I told the truth.”

“Isn’t it true you received cash gifts you did not report to the IRS?”

“Yes.”

The attorney looked confused. He expected a fight and got a woman telling him where her scars were. Brenda smiled with two teeth.

Savannah testified, her hair pulled back, no jewelry, like a woman entering a convent of accountability. Evelyn testified. Ethan wouldn’t look at her. He spent her entire testimony cracking the knuckles of his right hand with his left and staring at the table as if numbers might come to his rescue. The judge finally said, “Mr. Davis, knock it off,” and the sound stopped but the feeling of it stayed in the room like a tuned fork.

On the third day, Rafael testified. He told the jury how Ethan had stolen not just money but trust. He told them how he’d walked into his boss’s office once and found me sitting there with Adrian and the DA, and how Ethan’s face had gone “white as stone.” The jurors laughed quietly. The judge smiled with her eyes.

The defense put Ethan on the stand. He said, “I’m under immense pressure,” and “Everyone takes cash,” and “She’s my mother.” He said, “She hits herself.” That last one made the woman in the front row cover her mouth and the man in the second row shake his head and roll his eyes like a person who watches football and cannot believe the quarterback doesn’t see the open receiver.

The jury took four hours. They found him guilty on all counts: domestic violence, witness intimidation, corporate fraud, unlawful access to his mother’s bank account, and attempted obstruction of justice. The judge scheduled sentencing for a month later.

Meantime, life insisted on being lived. Northern threw a small welcome party for me in the break room with a sheet cake that said, “Monica: Order of Operations,” because Adrian makes dad jokes. Savannah moved into a one-bedroom apartment and texted me a photo of a plant on her windowsill with the caption, “Learning to keep things alive that don’t hurt me.” Clarice crocheted me a throw blanket the color of spilled sunlight and left it on my porch with a note that said, “For afternoon naps and evening courage.”

The day of sentencing, Ethan’s public defender tried for leniency. He talked about a rough childhood—he couldn’t find one, of course, because I gave him everything, so he talked about the absence of his father like it explained the presence of his fists. He asked for mercy. Brenda asked for justice.

When the judge spoke, the air shivered. “Mr. Davis,” she said, “you didn’t just steal money. You stole safety. You didn’t just threaten your mother. You colonized her house like a despot and attempted to annex her mind. You used legal language like a cudgel and familial language like a leash. This court believes in rehabilitation. It also believes in accountability.”

She sentenced him to twelve years for the corporate crimes and three consecutive years for the domestic charges, with a no-contact order that would ring like a bell if he ever came near me again. He said nothing. I wondered if it was because he didn’t have anything to say or because he had finally learned that silence sometimes makes a kind of cage.

After court, Savannah squeezed my hand. “Thank you,” she said again. “I want to go to the DA’s support group for victims. Would you…?”

“Go with you?” I said, and she nodded. We went. We sat in a circle of women who made casseroles and confessions and new lives. We learned to accept free pencils during budget cuts and to call one another when the late-night terrors came back. Human beings will rescue each other with rope or recipes. We do what is necessary with what we have.

That fall, Northern hosted a small luncheon to celebrate a new initiative: a partnership with the DA’s office and a local shelter to provide jobs for survivors reentering the workforce. Someone asked me to say a few words. I said:

“I don’t have a speech. I have a kitchen to go home to and a neighbor who knocks when my dishes pile up and a sister who shows up at lunches pretending not to know me when it keeps me safe. I have a job where my skills are valued in a way that makes me want to iron my blouse. I have a plant Savannah gave me that I have not killed. I have a son in prison who used to be a boy I loved and a woman I am becoming who can hold both those truths without breaking.”

They clapped. We ate sheet cake.

On a Sunday afternoon that winter, Clarice and I put up a pre-lit tree because I don’t want to fight with lights anymore. We hung ornaments that had survived the years in a box in my garage, plus a new one: a tiny figure of a woman holding a briefcase. We drank cocoa. Evelyn came by with a scarf she’d knitted and Rafael came by with a bag of oranges because his mother believes in vitamin C like a religion.

We sat around my table and told the truth. We told it like people tell jokes at funerals and bedtime stories to toddlers: with softness and timing and the knowledge that company is part of the medicine.

When they left, I stood in the kitchen—the site of so many humiliations, the place where soup became a weapon and then, later, a meal again—and ran my hand along the counter. I looked at the cabinet where I keep the fancy wine glasses Savannah liked. I took one down and poured two inches of the cheap stuff. I am not sentimental about wine. I drank it and didn’t flinch.

Before bed, I listened to one of the voicemails Ethan left the morning after his arrest. I do that sometimes—to remind myself the fear had a voice and that voice is now on the other side of a bar and a law and a decision. He cries in the voicemail. I suppose I could delete them. I suppose I will.

I turned off the kitchen light and climbed the stairs. The house made the small settling noises of a body falling safely asleep. I passed the mirror in the hall and did not look away from myself.

When Ethan walked into his boss’s office that day and turned as pale as chalk, a part of this story ended. What I do not want to forget is this: the day began in my kitchen. It began with eggs and coffee and a woman deciding she would spend the rest of her life naming things correctly.

My name is Monica. I am sixty-one. And while my son is in prison, I am not defined by that. I am defined by the neighbor who hid a camera in a bush and by a sister who came to lunch in a yellow dress pretending not to know me until the right moment, by a CPA who called me Mrs. Davis and meant it, by a lawyer who said, “Confess on your terms,” by a boss who apologized even when it wasn’t his fault, by a woman I once disliked who now sits next to me in a circle on Tuesday nights, and by the version of myself who discovered that courage can arrive late and still be in time.

People ask me sometimes if I’ve forgiven Ethan. The answer is complicated. I forgive the boy who was eight and cried in my lap when his father left. I do not forgive the man who used his hands and my bank account like weapons. Maybe someday I will. Forgiveness is an act of self-respect, not an absolution. For now, I wish him the help he refused to take when it could have saved us both.

I salted my soup tonight. I salted it exactly the way I like it. I sat at my table with the cheap wine in the fancy glass and the throw blanket on my shoulders and I ate without hurrying and without apology. On the counter, my phone buzzed. It was a text from Evelyn: Brenda says you were brilliant on the stand. Dinner Friday? I’ll bring dessert. I typed back: Yes. Always.

In the morning, I’ll ride the bus to work. Adrian will make a joke about semicolons. Rafael will hand me a file and call me “the backbone of this floor.” I will hang up my coat, straighten the stack of folders on my desk (I cannot help it) and get to work rebuilding systems and people and a life. And if I ever again forget the taste of my own strength, I will open the drawer where the foundation sits and remember that I covered bruises once to keep someone else’s story alive. Tonight, the only thing I cover is the pot on the stove to keep the soup warm for tomorrow.

The salt is just right. The silence is kind. And for the first time in years, when I turn out the kitchen light, the dark is mine.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My daughter-in-law slapped me in the face and demanded my house keys! CH2

My Daughter-in-Law Slapped Me in the Face and Demanded My House Keys! Part One The slap landed before I…

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing. CH2

My Husband Thought I Faked My Pregnancy, Then Pushed Me Down The Stairs To Test — My Sister Laughing …

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down The Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything. CH2

My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down the Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything Part One My…

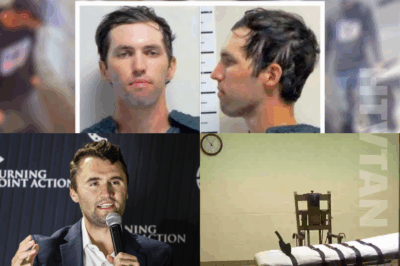

Suspect In Charlie Kirk Killing Could Face The DEATH PENALTY — Utah Signals An AGGRAVATED Murder Case

Prosecutors booked 22-year-old Tyler Robinson on aggravated murder, a charge that opens the door to capital punishment under state law….

“We will find you, we will try you and we will hold you accountable to the furthest extent of the law. And I just want to remind people we still have the death penalty here in the state of Utah.”

Utah Governor Spencer Cox Issues STARK WARNING — State STILL Has The DEATH PENALTY As The Charlie Kirk Case IntensifiesHours…

SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME “YOUR CHILDREN ARE MINE.”

“SIGN THE DIVORCE PAPERS OR I’LL BREAK YOUR NOSE” MY WIFE’S NEW BOYFRIEND, A GANGSTER, THREW THE PEN AT ME—‘YOUR…

End of content

No more pages to load