My Sister’s Prank Left Me Paralyzed—Parents Called Me Dramatic. The MRI Results Made Them Criminals

Part One

My name is Cynthia. I am thirty-two years old, and I can still hear the sound of my skull meeting stone—the obscene, hollow clack—like a cruel punctuation mark to a sentence I didn’t know was ending. I remember the string lights wobbling above the new patio, the blur of faces swarming and then receding, my sister’s laugh cutting through everything pure and mean. For a few stunned seconds my body forgot how to breathe; then the pain raged up my spine and vanished somewhere around my waist, as if my legs had been erased.

“Get up,” my father barked, as if he could scold gravity into reversing itself. “Quit making a fuss.”

My mother, more practiced with the veneer of civility, leaned down and hissed, “Enough. Not today, Cynthia. Don’t ruin Thanksgiving.”

The thing about being dismissed when you most need help is that it changes the shape of the room. The faces around you bend into masks; the ceiling becomes a lid. I lay there on the polished Italian travertine my father had bragged about all afternoon and felt nothing below the place my back had hit the stone lip of the fire pit. I lifted my head, and the world swam.

“I can’t feel my legs,” I said, and my voice wasn’t mine anymore. It belonged to someone younger and terrified—someone who had spent a childhood saying some version of this and learning it did not matter.

We looked good from the sidewalk. That was how it always worked with my family. Our San Jose house was the kind you imagine when you think of a certain American promise—sprinklers timed to pretend the drought didn’t matter, lawn as precise as a haircut, a door that always looked recently painted. Inside, the rules were simple and so strict it felt like you could hear them humming. Father: Harold—software engineer, mid-level manager, wall of a man who preferred performance reviews to feelings. Mother: Shirley—neighbor-friendly, casserole-carrying, nerves tuned to Harold’s temper and Angela’s moods.

And Angela: four years older, a honey trap of a person whose sweetness always came with teeth. She learned early how to play perfect: report cards lined up on the mantel like flags from conquered lands, a smile wide enough to reflect the room back at itself. She had a talent for pranks that crossed into cruelty and parents who called it “spirited.” I was seven when she told me the beehive in the eaves was empty and dared me to touch it: five stings later, Harold lectured me about curiosity while Shirley sighed about co-payments. At ten she hid my stuffed mouse and said Mom had thrown it away; at fourteen she swapped my finished art project with a blank canvas just before I left for school, and when I failed the assignment, Harold talked to me about “personal accountability.”

The lesson was relentless and tidy: if I got hurt, it was my fault for bleeding where people could see it.

At nineteen, I moved out and built a life with the kind of friends who do the showing up your family doesn’t. I found clients and pride as a graphic designer, learned to breathe in rooms without Angela’s gravity. Therapy gave me vocabulary for the weather inside our house. Still, guilt and habit have their own magnetism. When Shirley called in early November—“It’s important we’re all together; your father redid the patio; Angela will be here with Logan”—I felt the old tug and said yes before I remembered I could say no.

I told myself I would sequence the day like a professional: arrive after the crowd assembled so I wouldn’t be a spectacle; stay just long enough to prove I showed up; leave before Angela remembered how to laugh in ways that unscrewed me. I packed a bag and booked a room at a hotel because sleeping in my old bed felt like losing ground. I chose black jeans, a gray sweater, flats. It was the compromise Shirley had trained me into—presentable enough for Harold, mine enough for me.

By the time I stepped into the backyard the party had ripened. Thirty people clustered under a canopy of warm lights; wine tilted everyone’s posture toward careless. Harold held court at the grill, flipping steaks the way some men drive: with unnecessary authority. Angela stood near the new fire pit, gold hair pinned up to catch compliments, arm threaded through Logan’s. When she spotted me, her smile tightened on one side.

“Cynthia, you actually came?” she sang, pulling me into a hug with a grip like a dare.

“Happy Thanksgiving,” I said, already wishing for the cool quiet of the hotel. “The patio looks great.”

“Custom travertine,” she said, lazy wave at the stone. “Cost twenty grand. Daddy didn’t even blink.”

It is a special kind of skill, to weaponize price tags as if they were personality traits. I smiled at no one and drifted to the edge of things, into the safe zone populated by spouses and people who had wandered in because they love someone who loves someone who loves Angela. We talked weather and parking and where to get good coffee that wasn’t a chain. I stayed sober and watchful. If you grow up as the designated problem, you learn to manage variables.

As the afternoon bloomed into early dark the tone shifted. Angela’s cluster got louder, their stories grew meaner, and the old sport reappeared: Remember when we… “Cynthia,” she called, too bright. “Remember when we convinced you the backyard was haunted?” Laughter. Heat in my face like a sunburn from a long time ago. Logan, eager: “Or when we hid her sketchbook? God, you cried.”

With the kind of clarity that comes from humiliation followed by maturity, I decided to leave. I found the sliding door with my eyes and said to nobody in particular, “Heading out,” because some goodbyes don’t deserve a speech.

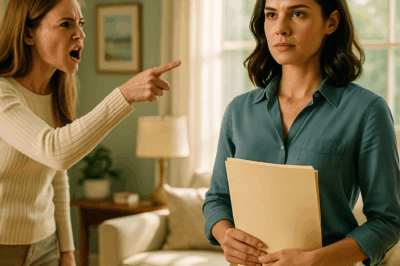

Angela stepped in front of me, smile sharpened into something you could cut yourself on. “Leaving already? Stay for dessert. Don’t be boring, Cynthia. Lighten up.”

“I have a long drive,” I said, careful on the edge of polite. I shifted to step around her. She moved with me.

The instant my foot hit the travertine I understood, then too quickly to save myself: it was slick—wrong slick. Not water; not a spilled drink; an oil-shine that made the stone perform like ice. My right foot slid forward; my left tried to compensate and failed. The rest of me followed physics and loyalty to pain. I fell backwards, quick and heavy. My spine slammed into the stone lip of the fire pit; the back of my skull met the corner with a thud that made the string lights twitch. Pain lit my back like a fuse and then extinguished everything below my waist. Sound shot out of me, primal and ugly.

For a breath I thought: Oh. So this is the kind of thing that happens to other people. Then the world rushed back in.

“Nice fall, Cynthia,” Angela said above me, smirking. “Really going for it.”

“I can’t feel my legs,” I managed. “I can’t—please—call—”

“Get up,” Harold barked from the grill, without turning. “You’re not a child.”

“She’s probably drunk,” Angela said to Logan. “Classic Cynthia.”

The sky, obliging and obscene, remained beautiful. I turned my head and vomited on travertine that had not asked for that kind of baptism. Panic flooded my limbs and found no purchase.

“Step back, please,” a voice said. Calm and competent. “I’m a nurse.” The crowd parted; a woman knelt beside me. “Hi, I’m Lauren,” she said, eyes level with mine. “I work in the ER at Stanford Health. Don’t try to move. Can you tell me what happened?”

“Slipped,” I said. “Hit the pit. My legs—”

She palpated along my shins and thighs, watched my face, watched my feet. “Can you wiggle your toes?” I stared at my feet—traitors at the end of my body—and thought them into motion. Nothing. Her jaw tightened the quietest amount. “I’m calling an ambulance,” she said, already dialing.

Shirley appeared, breath tight like she’d run from the kitchen. “That won’t be necessary,” she said. “She’s… having a moment.”

Lauren didn’t even look up. “Ma’am, your daughter has signs of a spinal cord injury. Moving her could cause permanent damage. She needs a trauma team.”

The part of me still attached to old habits noticed the way Shirley’s hand fluttered to her bracelet. “A spinal injury? Don’t be dramatic,” she whispered, as if I had staged it.

Harold arrived, his irritation now threaded with unease. “What’s this ambulance business?”

“Sir,” Lauren said, voice a scalpel sheathed in velvet, “your daughter likely has a serious spinal injury.”

He glared at the patio like it had betrayed him. “The stone isn’t slippery. I had it sealed last week—”

Lauren rubbed two fingers together where she had pressed the travertine by my fall. She held them up: sheen visible in the string lights. “This isn’t water,” she said, tone sharpening. “It’s some kind of lubricant.”

A silence spread out from those words the way a stain spreads on a tablecloth. People who had laughed leaned back and rebalanced themselves against their morals. Eyes slid to Angela, who, for the first time that afternoon, looked small. “It was just a dumb joke,” she muttered to the stone. “I put some of Dad’s deck sealant on a few spots. I thought she’d slip. Everyone would laugh. I didn’t think—”

“That,” Lauren said, “was not a joke.”

Sirens grew out of the street. They sounded like sanity.

Two paramedics and a captain moved through the backyard like a tide with purpose. The lead—Emma—knelt where Lauren had been, her face attentive but not yet concerned enough to frighten me more. “Hi, Cynthia,” she said. “I’m Emma. We’re going to put a collar on your neck, then roll you onto a backboard. Don’t move unless we tell you to, okay?” I nodded because I had learned early how to obey orders that felt like safety.

“Was the patio wet?” she asked Lauren while fitting the collar. “Or slick with something?”

“Lubricant,” Lauren said. “Sister admitted to applying deck sealant so someone would slip.”

Emma’s gaze flicked to Angela and back. “Mark,” she said to one of her team, “document the surface and take sample.” He pulled out a camera and evidence kit as if their presence had conjured a new layer of reality. Emma counted the roll. Pain shot through me so clean it felt like truth. They secured me, started fluids, oxygen. “BP’s low,” the second paramedic—Jared—said to Emma. “Let’s move.”

“Will she be okay?” Shirley asked, and for the first time I heard true fear.

“We’re doing everything we can,” Emma said. “But spinal injuries are time-sensitive.”

“Police,” Emma added into her radio, “please respond to a potential criminal negligence.”

Harold stiffened. “Criminal? This is my house.”

“This is someone’s spine,” Emma said evenly.

They lifted me. The world tilted; the lights streaked; I stared straight up and watched the faces of the people I’d known my whole life rearrange themselves into reflections of who they actually were. Angela’s mouth opened and closed as if she’d lost the line; Logan stood behind her, unhelpful for the first time in his life. Harold moved toward the front yard fast, perhaps to talk the sirens into something more reasonable. Shirley wrapped her arms around herself like a sweater.

As the stretcher cleared the doorway, the first flashing lights reached the house. For the first time since I fell, I felt something like relief. Not in my legs. In the part of me that had longed for anyone in authority to say, I see it. It’s real.

I woke up twelve hours later in the bright cleanliness of an ICU room at Stanford Health. “Hey, Cynthia,” a nurse said. Badge: Javier. Tone: gentle. “You’re safe. You’re in the hospital.”

I saw two rods on the whiteboard under my name drawn in squeaky black marker like exclamation points. A woman in a white coat entered with the kind of gravity that is earned, not performed. “I’m Dr. Patel,” she said, sitting so her eyes were level with mine. “Your neurosurgeon.”

“What,” I said, because that was the only word left, “happened?”

She showed me MRI images: white-and-gray cross-sections that looked like weather maps. T12–L1: the spine’s hinge between middle and lower back. “You sustained an incomplete spinal cord injury,” she said, pointing to the grainy place where bone should have been clean. “The fall fractured two vertebrae and compressed the cord. We took you to surgery to remove bone fragments and stabilize the spine with rods and screws.”

“Will I…?” I swallowed because this was where denial thinned into truth. “Walk?”

“With incomplete injuries,” she said, “there’s potential for recovery. Some regain a great deal; others less. Early immobilization and early care make a difference.” A shadow crossed her face, a flicker of anger she couldn’t prevent and didn’t explain yet. “We’ll know more as swelling decreases. We’ll start rehab soon.”

“Police will want to speak with you,” she added, almost gently. “When you’re ready.”

I was ready because I had waited for decades to tell someone the whole story who could not afford to pretend it wasn’t what it was.

Detective Ramirez and Officer Lee came in with notepads and eyes that did not flinch. I told them everything: the taunts, the slick stone, the fall, the gasping plea, the fifteen minutes of being told I was ruining a holiday. “Paramedics documented the substance,” Officer Lee said. “A sample’s in the lab. Neighbors’ cameras picked up some audio; we have witness statements. We arrested Angela for reckless endangerment causing serious injury. We’re recommending charges against your parents for negligence and failure to provide aid.”

“Charges,” I repeated, not because I doubted them but because the sound of the word in connection with my parents defied the logic my bones were built on. “They could—go to jail?”

“Maybe,” Ramirez said. “Legal consequences take time. Your job now is recovery.”

Recovery, it turned out, was work that changed definition every week. First recovery was breathing without my throat hating me. Then it was learning how to sit up without feeling like my spine would shatter again. Then it was a daily pilgrimage to the rehab gym in a wheelchair that forced me to understand the world’s secrets: which doors claim to be accessible and are not, which halls are too narrow for grace, which people lower their eyes when they see you because disability scares their stories.

My physical therapist, Ryan, was the kind of encouraging that borders on aggressive in the best way. “We’ll fight for everything,” he said, clapping his hands. “Your body will surprise you. Trust it. Also, curse it when it earns it.” In occupational therapy I learned how to transfer into a car with hand controls and how to cook without standing and how to ask for help without swallowing glass. In group I met Mia, who fell from a ladder changing a light bulb last year and spent four months angry. “It’s a lot,” she said, sipping terrible coffee. “It won’t always be everything.”

Dr. Patel explained my injury in terms that left room for hope and boundaries. “Some sensation is back,” she told me three weeks in. “A good sign.” Sometimes my thighs tingled like they had fallen asleep and were waking into a life that felt unfamiliar. Sometimes pain radiated in invented places. The human body is a strange house; getting to know mine again felt like re-acquainting with a childhood home after it had been remodeled by someone with different taste.

A social worker named Ethan walked me through logistics. “We’ll modify your apartment,” he said. “Ramps, bathroom, counters. There are grants. There’s help. You’ll be okay.”

The county issued a temporary restraining order against Angela after she tried to send flowers and a card through a friend from her book club: It was a joke gone wrong. Please forgive me. The DA—Karen Lopez—met me with what the movies never get right: kindness with teeth. “We’ll take a plea if it’s real,” she said, “but we’re not here to rescue anyone from consequences.”

In a meeting room that smelled like lemon cleaner, my civil attorney, Steven Harris, spread out my future like blueprints: medical bills, lost wages, home modifications, care. “Spinal injuries are expensive,” he said. “Your case is strong. Their insurance will fight. We’ll win.” He didn’t ask if I wanted to sue my family. He said, “This isn’t revenge. It’s survival.”

The MRI images made my family criminals in the eyes of the state; the memory of “get up” made me a plaintiff in the eyes of my hard-won adulthood.

Part Two

By spring the law had done what the law does at its best: transmuted denial into tidy paragraphs. Angela pled to a felony count of reckless endangerment causing serious injury. Four years, the judge said; eighteen months inside, the remainder on probation with counseling and community service and a restraining order that held its boundary better than my parents ever had. Harold and Shirley pled guilty to misdemeanor negligence: probation, 300 hours of community service, mandated classes on first aid and caregiver responsibilities. There was no jail for them. There was, perhaps for the first time in their lives, a lesson delivered by someone they could not shout down.

The civil suit took longer and cost energy I had to borrow from myself. Steven deposed my family in a conference room with a window onto a parking lot and a coffee machine that never worked. Angela cried, then did not; Logan said I didn’t think more times than I imagined possible and always as if it were a defense. Harold tried to be angry into eloquence and came up with nothing but bristle. Shirley said, “We thought she was being dramatic,” and then the part of me that had once wanted her to take my temperature with her palm went and sat in a different chair.

We settled five months after filing. Their insurer wrote a number with both weight and apology: $1,000,000 toward my past and present medical bills. Their assets—house on a street they’d described as “nice enough,” savings they had once called “for our future”—went into a trust established in my name for $1,500,000. It wasn’t a windfall. It was a lifeline. It bought ramps and rods and attendants and quiet. It turned revenge into resources, which is the only worthwhile alchemy I believe in now.

When I left rehab and rolled into my apartment, it felt like a new country with my furniture in it. The bathroom had grab bars like punctuation you could hold. The stove cooperated with a seated cook. The car in the lot had hand controls that made independence feel like a verb I could still conjugate. My company reconfigured my role to remote; I learned to fall in love with outputs more than the posturing in rooms I couldn’t enter easily anymore.

Therapy with Olivia was a different kind of rehab. We took apart the story of a family that had called me dramatic until the MRI tried to eradicate me. We looked at a father who had told his utilitarian version of love; a mother who had kept her house and lost her daughters; a sister who had never told the truth about what fun cost her. Olivia said, “You were dismissed so long you learned to audition for empathy. You don’t have to anymore.” Some days that sentence was a key. Some days it was a mirror. On hard afternoons when grief laid out all its parts like a mechanic who didn’t plan to put anything back together, Olivia kept me company.

A year after the fall, Angela sent a letter from prison. My hands shook opening it and I hated that they did. She wrote that therapy had cracked her open, that she had a name for the way she thought bored was a problem other people should have to solve; that she understood now harm is not erased by intention. She apologized without using the word if. “I don’t expect forgiveness,” she wrote. “You deserved better. I am sorry.” I put the envelope in a drawer next to childhood drawings. Maybe someday the letter will become a bridge. Maybe it will stay a map of how we got here.

Harold and Shirley moved to Arizona. Ava heard from someone at church that they tell people I had a tragic accident and that they supported me through it with every resource. In their version I am a lesson without a history. In mine they are a cautionary tale with a forwarding address. We have not spoken. Sometimes my phone remembers their ringtone and my heart races for a second like a muscle being tested by a trainer who doesn’t know your limits. Then it passes.

Some things got easier. I found a support group of people with bodies that had transfigured in an afternoon and spirits that had learned to bend without breaking. I started mentoring new arrivals on the ward, which felt like time travel: “You won’t always feel like a problem,” I told a nineteen-year-old who kept apologizing for crying. “You’re allowed to be a person.”

Some things got lovely. Nathan, a physical therapist who made me laugh by accident and on purpose, sat with me in the hospital cafeteria one day and said, “I like who you are more than I like the story about what happened to you.” It was the sentence that made me brave enough to have a life again that contained a person who could disappoint me without breaking me. We are something that takes turns: when I stand, he doesn’t hover; when I fall, he doesn’t call it destiny. He has seen me angry and made me tea anyway. He knows where I keep my humor and how to fetch it.

Some things got big. Six months ago I finished a master’s degree in user experience design with a focus on accessibility. It felt like an audacious way to tell the world: make room. Next spring I’ll consult with companies building tech that wants to include bodies like mine and always misses until someone at the table tells them where the door is.

Recovery is not an adjective. It is a practice. Some mornings my legs tingle awake and let me stand with braces, and I can move through the apartment with crutches like a person reclaiming ground. Some afternoons pain bolts through me like weather and I ride it out. Some nights guilt still finds me in the shape of if I hadn’t gone to dinner; some dawns anger strides in with if they had listened. I meet them both on the porch of my mind and let them talk until they are tired. Then I roll back inside and make breakfast.

I still think about the day under the string lights on the travertine my father loved more than my voice. Not because I want to. Because my body insists upon it. I think about Lauren’s calm hands and Emma’s decisive voice; about a universe in which a stranger’s training mattered more than a family’s myth. I make gratitude a daily verb in their names.

Last week I wheeled into the rehab gym with a bag of cookies from a bakery that had finally learned how to design their counter so a seated person could reach their own pastry. Mia waved. A new guy—Evan—watched me transfer to the mat without help and said, “How do you keep doing it?” I told him the truth that feels like a lie until it fits: “Pain shapes you. But it doesn’t have to own you.”

On the second anniversary of the fall I went back to therapy and told Olivia I was happy. It felt like sacrilege. She asked me to list the ways. I did: coffee with neighbors who learned how to slow their gait to mine without practicing pity; work that remembered me when I had disappeared into a hospital bed; a body that surprised me with its ability to adapt; a man who sees me and not my fear; a future that includes stairs that do not defeat me because there will be ramps and friends and stubbornness.

If your hurt has been called drama and your pain has been told to be quiet until it learned to whisper in your bones, hear me: you do not need permission to insist on your reality. You do not have to audition for your own life. Find your Lauren. Learn your Emma’s name. Call Dr. Patel when people tell you to get up. File the report. Hire the lawyer. Take the settlement. Buy the ramp.

And then—when the sirens fade and the house is sold and the letter sits in a drawer and the world resumes its ugly-beautiful, ridiculous-compassionate spin—make something with it. A degree. A garden. A joke. A morning where you remember to choose the mug you like best because you get to.

The MRI images made my family criminals. My spine made me a plaintiff. Neither of those will ever be the whole story. The whole story is this: I have built a life that keeps loving me back. I get to decide where my home is now. And I am not dramatic. I am alive.

END!

News

I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” ch2

I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” — So I… …

After I Caught My Husband With His Mistress, My Mother-in-Law Threw Me Out of the House. ch2

After I Caught My Husband With His Mistress, My Mother-in-Law Threw Me Out of the House—But… I grew up in…

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… CH2

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… Part One I…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited me Over Just to Tell me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited Me Over Just to Tell Me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her …

At My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. CH2

My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. Part One…

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And then.. CH2

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And…

End of content

No more pages to load