My sister’s husband made her sleep outside under a tree with nothing during a storm while she was pregnant, i took my sister to a five-star hotel. The next morning, i showed up at her husband’s firm. His boss had called an emergency meeting. They turned pale when i walked in.

Part 1

The storm had already passed by the time my phone rang, but it still sounded like weather inside the call—wind snagging on the line, rain strafing whatever the microphone could catch, branches making their dry, brittle protests. It was midnight and the number on my screen was unknown, yet my bones recognized the call before my eyes could. My sister. The one who never asked for anything. The one who had been taught by the wrong man that asking was the same as failing.

She tried to speak and made a sob instead. Not the loud kind that wants rescuing—this was the shivering sob of someone who has run out of the energy required for dignity.

“Where are you?” I asked.

A pause that felt like glass pressed to my ear. “Under the tree,” she whispered.

Three words. They shouldn’t be enough to rewire a life. They were.

“He said I didn’t deserve a roof tonight.” Her voice faltered. “I’m okay… the baby’s okay… I think.” The call dropped. The sound that followed wasn’t silence but a roar in my head, the single hot rush of having your purpose chosen for you.

I didn’t put on proper shoes. I didn’t tell anyone where I was going. There are nights when titles—sister, aunt-to-be, problem-solver, woman-who-has-had-enough—don’t need a phone tree. I drove through streets that shone like peeled fruit, the storm’s last threads flicking across the windshield, and found her exactly where she said she was: curled under a bone-pale maple like a cast-off, hair slicked to her cheeks, jacket soaked through, one arm wrapped around her belly as if arms could bargain with lightning.

She looked at me and tried to smile like she was the one who needed to reassure me.

“Up,” I said, and between us—my jacket over her shoulders, a blanket from my trunk around her knees—we made the shape of leaving. I didn’t knock on the door to the house thirty yards away where warm light pooled in a living room he wouldn’t let her enter. I didn’t give him the dignity of knowing I was there. We got into the car, heat full blast, my hand on the back of her head the way I did when she was five and morning was difficult. Ten minutes later the storm was an anecdote behind us; fifteen minutes after that, a porter in a gold-trimmed jacket was showing us into a room whose air smelled like money and citrus.

“Just one night,” she whispered, already apologizing to a ledger she hadn’t seen. “I’ll pay you back. I’m sorry.”

“Stop,” I said. She did. Not because my word is magic but because sometimes the body knows when to be commanded. I called down for chamomile, extra blankets, dry clothes from the boutique. When the bath ran I left her with steam and closed the door, sat on the carpet with my back against the bed, and made a list on the hotel notepad because lists are the only ritual I trust.

- Doctor.

- Lawyer.

- Locks.

- Phone records.

- The quiet part.

The quiet part: let him think the storm ended.

At dawn, she slept, finally, hair fanned across a pillow that had held people who believed they’d earned their comfort. I watched the line of her breath under a borrowed robe, one hand splayed protectively over the swell that made everything urgent. She murmured, the small jobs the mind does to ease itself. I didn’t wake her. I took the second phone I rarely use and began to dial.

The obstetrician answered like mercy. “No bleeding is good,” she said. “But bring her in. Storms cause stress; stress causes cascades.” We went before breakfast; the ultrasound screen filled with the insistent rhythm of a heartbeat performing indifference to adult stupidity. “Baby looks strong,” the doctor said. “You did the right thing.”

Lawyers answer differently. Karen Lee was all clipped syllables and steady hands. She listened. She didn’t interrupt. When I finished, she named what had happened in words that could live in a court transcript: coercive control, financial abuse, endangerment. “If she wants out,” Karen said, “we can make out happen. Quietly if possible, loudly if required.”

I asked for quiet. Not because loud frightens me. Because quiet has better aim.

When we returned to the hotel, room service had set out eggs that steamed and fruit that glittered with a ridiculous shine. My sister barely looked at the tray. “I didn’t wake you?” she asked, and then she saw I had shoes on. “Where did you go?”

“Doctor. Lawyer,” I said. She touched her belly; we smiled the kind of smile women make when the most important thing is still okay. She ate a forkful of eggs like a person who had been told she was allowed to.

“I should text him,” she said after, hating the sentence and still trained to test a leash. “He’ll be furious.”

“He’s already furious,” I said. “That’s his hobby. Let him practice it alone.”

While she showered, I opened my laptop and wrote emails I’ve practiced in other lives: one to HR at her job asking for emergency leave; one to a locksmith; one to a friend who runs a charity’s storage unit that contains, among other necessities, the basics a woman needs when she leaves with only her phone and her courage. The friend wrote back with a list of available boxes and a final line that made the back of my eyes sting: I’ll be downstairs in fifteen with coffee. I brought biscotti because biscotti feel like hope.

By noon the car was a Tetris of supplies—maternity leggings, two pairs of decent shoes, toiletries, a winter coat that didn’t make her feel like a tarp. I drove to their house again because I needed to see it in daylight. The lawn shone in that arrogant way lawns do after rain. A ceramic welcome sign hung by the door as if irony were a design choice. Curtains closed. Mailbox open-mouthed with junk mail. The maple tree was not a metaphor anymore; it was a witness.

The locksmith met me at the back gate. He changed what could be changed and scheduled what needed approvals. “Are you sure?” he asked, because even men who know how to make doors answer to new keys sometimes prefer a scene where peacekeepers mediate, hands on everyone’s shoulders.

“Yes,” I said, and the word didn’t echo.

The quiet part required patience and a browser history that could stand up in court. I am good at both. I took the phone records first: late-night calls to the same unlisted number tagged Work B in his contacts. (Men like him understand that the trick is not to hide, but to rename.) A second phone—registered under a cousin’s name—pinging from hotels his expense reports would call “client dinners.” Bank activity that sang in the particular key of contempt: cash withdrawals near jewelry stores; payments to a baby boutique in a city my sister had never visited; a lease for a storage unit three exits off the freeway in a direction that led nowhere she would ever go on purpose.

I didn’t tell her. She slept, and I fed the machine that would change her life.

Storms pass; hangovers arrive. At nine the next morning, his firm called me back. My message the night before hadn’t said much—my name, a request for a short meeting with the managing partner, a note that I might be bringing information that could affect client trust. The kind of vague that eats an executive from the inside.

“Emergency meeting,” the receptionist said. “Ten-thirty.”

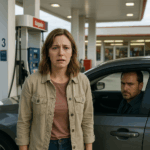

The lobby of his firm looks like money learned how to levitate. White stone, silhouettes of men who think the right to speak is a birthright, a receptionist whose smile knows how to become a shield. My heels sounded the way I needed them to sound. When the partner—Alec Beaumont, gray at the temples, skin the color of polished mahogany—saw my face, he stood. “We received your message,” he said. “Let’s go to the boardroom.”

Between us, the table could have been an airstrip. He sat. I remained standing until the door opened again and my brother-in-law—Daniel, calling himself Dan to clients and “provider” to my sister—slid into a chair two from the end. He went paler when he saw me. Another partner took the seat between us. Associates filed in like they’d been summoned to witness the lesson that keeps a firm’s name shiny.

“We’re here because Ms. Rao”—Alec flicked his hand to me—“requested an audience regarding a matter that may affect the firm.”

I set the envelope on the table. No theatrics. Just paper. His name on the tab. A second envelope, thinner, with a Post-it on top: For HR. A third, with another Post-it: For the managing partner only.

He tried to talk first. Of course he did. “This is a private matter,” he said, reaching for a tone that had always worked on waiters and wives. “My wife is unwell. She left the house last night against medical advice. My sister-in-law is… overreacting.”

“No,” I said, and that was all. The room tilted toward me as if the HVAC had changed direction. I slid the main envelope to the center of the table and untied the string. The first page was a photocopy of a text: Under the tree. He said I don’t deserve a roof. The second page, a timestamped photo of the maple and the woman beneath it. The third, the obstetrician’s note: Patient reporting exposure to inclement weather. Fetal heart rate WNL. Recommend safe housing. Words that know how to keep a judge awake.

Then the rest. Transactions. Call logs. An invoice with a bottled-water brand’s logo on the top from a hotel that sells privacy by the hour. A lease document for the storage unit with a photo of his signature—careless, arrogant, matching checks the firm had on file. A printout of a group chat where he performed intimacy for a woman whose name wasn’t my sister: my wife is such a martyr lol. thinks pregnancy means she’s fragile. A screenshot of a delivery confirmation for a bracelet my sister had cut a picture of from a magazine and taped to their fridge—a hint, a hope—sent instead to an address in a luxury building downtown.

He reached, metaphorically, for a match. “This is a misunderstanding. She’s hormonal. We argued; she wanted fresh air—”

“Don’t,” Alec said, not looking at him.

I placed the HR envelope atop the stack. “There’s a second phone registered to a false identity,” I said, “and a pattern of charging… extracurricular hospitality… to client entertainment accounts.” I didn’t elaborate. I didn’t need to.

“Who gave you this?” he asked finally, and though his voice was steady, his hands had found the table’s edge the way drowning men find a log.

I sat. I crossed one leg over the other. I folded my hands. “Your wife,” I said, because truth doesn’t need weaponry. “You left a pregnant woman under a tree in a storm. You forgot what a witness is.”

The managing partner looked like a man doing math faster than he was designed for. Liability. Press. Governance. “This firm does not tolerate the misuse of client funds,” he said, the way you say a line from a handbook when you’re deciding which chapter to turn to next. “Nor behavior that endangers vulnerable people, especially when it intersects with reputational risk.”

“I’ll… make it right,” Dan said, that male vow that assumes the world will continue to let him put out fires he started by paying for the water and sending a bill. “We’ll handle it. In private.”

“Your idea of private is what got you here,” I said.

The thing about a room full of people who manage risk is that they can smell a burn. Their eyes were already leaving him, already trying not to look at me like I was something to be feared. I’m not. I’m something to be believed.

I slid the final envelope—For the managing partner only—across to Alec. Inside: a simple summary, lawyer-ready, of the worst of it. I gave him the courtesy of being the first to read, the first to react, the first to decide whether the words immediate suspension pending investigation would be said in public or behind a closed door and then leaked.

“Leave your badge with HR,” he said after a minute. “And your firm phone. We’ll be in touch this afternoon.” He didn’t say you’re done. He didn’t need to.

When I stood, Dan stood too. “You can’t do this,” he said, but he wasn’t looking at Alec anymore. He was looking at me, as if I’d moved the sky.

“You did this,” I said, and walked out.

Back at the hotel, my sister was at the window in a robe too plush to be real, looking at the city like it might be a place that wanted her. I poured tea. I brought her honey. She touched the faint bruise the hotel’s makeup artist hadn’t fully hidden and smiled at me the way wounded people do when the morphine hits. “What did you do?” she asked.

“Only enough,” I said. She nodded. She didn’t need details. Safety makes explanation optional.

Night found us in the lounge where carpet hushes voices. A woman at the piano played the kind of song most people call jazz. My sister had two sips of a pear mocktail and looked less like a person who had slept in a storm. I checked my phone once. A single email from Karen: Temporary protection order granted. Hearing in ten days. I’ll be there. A second from the locksmith: Back door complete. Front scheduled for Friday. New codes set.

I watched my sister watch the piano player’s hands. Somewhere in a conference room, a man who believed cruelty proved power was learning that paperwork can make a person choke. Revenge is too strong a word for a night that ends with a lullaby and a court document. Precision is better. And silence, deployed correctly, is an instrument.

“I don’t feel sorry for him,” my sister said, not quite a question.

“Good,” I said. “We’re fresh out of pity.”

When she slept, I stood at the window and watched a ribbon of taillights wind along the freeway. The storm had scoured the air. Seattle glowed like it had been washed and put back on a hanger. I breathed. My phone buzzed once more, a late email from Alec’s assistant—formal, chilly, grateful. Thank you for bringing this to our attention. The firm takes these matters seriously. They always do once the receipts are printed.

I turned off the lamp. In the dark, I could hear my sister’s breath and the soft hum of a city pretending it never hurts anyone on purpose. I am not a violent woman. I am a woman with a list and a printer and a memory. Sometimes that’s the sharpest thing in the room.

Part 2

The morning after the boardroom, the sky was an expensive blue, the kind you see in brochures for people who believe they can buy their way out of weather. A tray appeared with pancakes and strawberries and a carafe of something that called itself coffee because it was served in a silver pot. My sister ate like someone converting hope into tissue. Her phone buzzed twice on the nightstand. She didn’t move. The temporary order comes with a gift: the knowledge that you owe no one your attention.

“Walk?” I asked after breakfast. We did, a slow circuit around the block with a scarf wrapped high and a hat pulled low, two women who looked like sisters who had recently cried for different reasons. In the hotel’s florist window a woman arranged white flowers into a logic I couldn’t parse; outside a cafe, two men argued like the world would end if they agreed. The planet continued to spin, unbothered by the way our private wars escalate.

Back upstairs, I called Karen from the bathroom so my voice would be small and tiled. “Proceed with filing for separation,” I said. “He’ll predictably propose therapy. He’ll send flowers. He’ll write emails that would sound reasonable to anyone who didn’t read the forensics. Ignore him. File.”

“Already on my desk,” she said. “We’ll also petition for exclusive occupancy. Given the endangerment, judges don’t like poetic defences about trees.”

“Thank you,” I said, and when I ended the call I looked at my face in the mirror and saw my mother’s eyes. I did not love that. I took one breath and turned the water on and washed.

By afternoon, the firm’s public-relations response had made its way through the feeds: an anodyne sentence about values and stewardship. Internally, a memo with teeth. Externally, silence toward anyone who didn’t have a subpoena. Dan texted from numbers we blocked as quickly as they arrived: Let’s talk. Then, We owe it to the baby. Then, the one abusers use when every other door is locked: You’re overreacting. I sent them all to a folder named EVIDENCE with the date on it.

The third day, the storage unit cracked open like a confession. The manager didn’t blink when Karen’s paralegal handed over the order; he’d seen worse secrets stacked floor to ceiling. Inside: boxes labeled in a handwriting I didn’t recognize—her name, but as if a stranger had practiced it. Two garment bags with suits a size she couldn’t wear, receipts pinned to the zipper with a binder clip. A velvet box with a bracelet that matched the magazine cutout on my sister’s fridge, only not for her. A shoebox with a second phone, the kind of burner used by people who still believe in clichés. A photograph of a woman who wasn’t my sister wearing a maternity dress my sister had pointed to in a store three months ago and then put back on the rack with a laugh that sounded like surrender.

I could have vomited. I didn’t. I cataloged. I photographed. I sealed and initialed. I sent copies to Karen. I returned the rest to the unit and changed the lock. I am not a petty person. I am meticulous.

That night, my sister asked again. “What did you do?”

“I put paper in front of a man who likes to pretend paper is just paper,” I said.

“And he—”

“Is learning how heavy paper can be.”

We moved her from the hotel to a short-term apartment that smelled like new paint and possibility. The charity boxes arrived—the tidy generosity of strangers: kitchen basics, sheets, a lamp that didn’t look like a compromise. I stocked the fridge with food that was hers simply because she wanted it. The baby kicked like a metronome under her sweater. The apartment made the sound empty spaces make when they are about to become story.

Day five, the firm called to say Dan had been suspended pending investigation. Day seven, HR called my sister directly and asked if she needed connections to resources—shockingly humane, likely transactional, not unwelcome. Day eight, his lawyer sent the first volley: We propose reconciliation therapy. We answered with a reference to a statute and a line that was almost a poem: No therapy cures contempt. Day nine, the court set the hearing date for a full protective order. Day ten, my sister’s doctor wrote a letter in the kind of language judges love: Continued exposure to psychological stress may endanger maternal and fetal health.

In the middle of all that, my sister laughed once in a way I hadn’t heard since she was nineteen—head back, eyes closed, unafraid of what would fall into her open mouth. We were at a thrift store buying a ridiculous lamp shaped like a flamingo because sometimes freedom looks like bad taste. A child tugged at his mother’s sleeve and pointed at my sister’s belly with the grave wonder children save for eclipses and pregnant women. Is there a moon in there? he asked. We laughed so hard we couldn’t talk. I put the lamp in the cart. The world kept not ending.

I did not tell her everything. I did not tell her about the other woman—pregnant too, due a month after my sister, believing a different set of lies. When we eventually told her, it would be with Karen in a room with Kleenex and water and a plan. But for now, my sister deserved the gift of building before the next demolition.

When the hearing day arrived, she wore a dress the color of new leaves and shoes that made sense. The judge was a woman whose hair had decided it had better things to do than perform. She listened. She asked the right questions. She read the right documents. She didn’t say I believe you in so many words; she didn’t need to. The order became permanent enough to breathe in.

Dan spoke once, words threaded through with an apology that had no verbs. The other woman didn’t show. His lawyer tried to sell a future where he learned from his mistakes, and the judge asked the one question men like him aren’t trained to answer: What will you do differently that isn’t a sentence that begins with “I feel”? He looked at his hands. The order stands.

After, in the courthouse hallway that smelled like floor cleaner and history, my sister sank onto a bench and put one hand over her belly and one on my wrist. “I’m tired,” she said. It was not a complaint. It was a measurement.

“I know,” I said. We sat there long enough to learn the bench’s squeak. Then we went home and I made pasta with more garlic than any reasonable person uses, and we ate it standing at the counter because chairs felt like ceremony and we weren’t in that mood.

The firm’s investigation finished in the way corporate investigations do—two paragraphs emailed at 4:57 p.m. on a Friday. Behavior inconsistent with company values. Termination effective immediately. Severance withheld pending resolution of expense irregularities. In kinder words: you are not special; you are not above a spreadsheet.

He moved out of the house he had treated as a stage and into a rental whose windows faced a wall. The other woman’s baby arrived early. He posted nothing. My sister’s belly grew into a geography that made complete strangers kind to her in grocery store lines. I painted a dresser yellow because babies like color and because a person can love a color so much it feels like a decision.

Sometimes violence is grand; mostly it is boring, a series of small arrogances. He violated the order once—showed up at the apartment door with a face tuned for contrition and a scarf held like an offering and a phrase he believed belonged to him, we owe it to the baby. I called the police without stopping to feel polite. They arrived and taught him about numbers printed on paper. He left learning what it feels like to be told no by someone who means it.

My sister started sleeping through the night again around the time the cherry trees in the park near her place forgot December. She had a ritual now: tea at nine, the book with the dog on the cover that makes her laugh without failing, a lotion that smells like the good part of summer. I wrote code for a client who didn’t care about my life; I watered a plant that will never feel guilty; I ran a finger along the sharp edge of a picture frame to remind myself that objects have the decency to be exactly what they are.

Two months later, at three in the morning, I woke to the text that changes a life twice: at the hospital. it’s time. I broke three small traffic laws getting there and arrived in time to hold a cup for her and call the nurse when her breath went lava and tell her that yes, the world is ridiculous but also beautiful, and also, you’re a god. A baby made a noise like a bird learning itself. My sister cried the precise number of tears required. I cried more. We held a person who didn’t know anything about storms and made promises we have every intention of keeping.

When the nurse left us alone, my sister looked at the tiny pink hat and then at me. “I keep thinking about that night,” she said. “Under the tree. How cold it was. How loud the world felt. I keep thinking… how is this the same planet?”

“Same planet,” I said. “Better story.”

We named the baby after Dorothy, the woman who taught me how to find a problem’s true size and then bring it the right tool. We went home two days later to an apartment that smelled like warmed milk and laundry. I built a bassinet by following instructions written for someone with less stubbornness. My sister slept like a person whose body had finally recieved the memo that she was safe.

The other woman reached out six weeks after her baby came. A message arrived that began with you don’t know me and ended with I think you might know what I should do. Karen and I met her in a coffee shop with bad scones and good towels in the bathroom and we did what women have always done: we spread paperwork on a table and told a stranger the parts of our story she needed to borrow.

By summer, my sister had a lawyer who spoke only when it helped, a pediatrician who takes her calls, a court order that keeps working when sleep doesn’t, a job she can do three days a week without someone calling it a luxury. By fall, a judge had approved a parenting plan that does not indulge men who want to be fathers on alternate Tuesdays. By winter, the house had been sold, the proceeds split accord to law rather than expectation, the maple tree standing like a witness who finally got to rest.

I don’t believe in cosmic math. But there is a kind of justice in watching a woman you love sit on a couch that belongs to her in a room that feels like a decision and feed a child who only knows softness while a dryer murmurs and something in the oven goes golden. There is a kind of justice in walking into a roomful of men in breathable suits and letting paper do the talking. There is a kind of justice in revenge that doesn’t call itself revenge, only enough.

A year after the storm, we went to the park with a blanket and pretended the geese weren’t plotting anything. Dorothy—the small one—stood on the grass with a wobble that looked like a speech about to happen. My sister kissed her head. The wind lifted the edge of the blanket and then thought better of it. The sky minded its business.

“I never asked,” my sister said suddenly, eyes on the baby. “Why his boss was pale when you walked in.”

“He’d already called an emergency meeting,” I said. “Someone had forwarded my message. Men who run things can smell fire through glass.” I looked at my niece, at her cheeks performing the comedy of cheeks. “And because they know exactly where their reputations live.”

My sister nodded. “Sometimes I think I should have… shouted more,” she said. “To make it count.”

“You made the only noise that mattered,” I said. “You called.”

She laced her fingers through mine. The baby gurgled like a brook deciding to be a river. A cloud crossed the sun and the world dimmed and then brightened like a hotel room light on a dimmer the first time you figure out how to use it. We breathed. We were the kind of quiet that doesn’t beg to be forgiven. We were the kind of women who have sharpened their silence into a tool.

Men like him don’t stop until someone makes them. Sometimes that someone is a woman who orders chamomile at midnight and carries a blanket and knows how to print the right page. Sometimes it’s a judge with good posture. Sometimes it’s a managing partner who remembers he has a soul. If you’re lucky, it’s all three.

The storm passed. The tree kept its leaves as long as it could. The hotel wrote “welcome back” in a calligraphy that made us laugh. The firm learned to check expense reports with a little more interest. And my sister—my only—sleeps with her window cracked to hear rain when it is kind, and her baby learns, as we all do if the world cooperates, the difference between water you can stand in and water that tries to take your name.

I don’t feel pity for him. Pity is wasted on men who mistake cruelty for power. What I feel is clarity. A quiet certainty that his ruin didn’t need me after a point; I only had to give it a nudge and a name. I will never need to lift a hand again.

Because sometimes the most devastating revenge isn’t spectacle. It’s the envelope. It’s the knock you don’t answer. It’s the calm. It’s the way a woman walks into a room and lets the air do the math.

And sometimes it’s this: a woman at a window with a child on her hip, looking out at a sky that no longer pretends not to see her.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I Was… CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Hit Me, Pushed Me Out, and Said “Get Out of My House” — and I…

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… CH2

My Dad Yelled, “Pay Rent Or Get Out!” At Christmas Dinner, So I Left And Cut Off Every Expense… …

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner. CH2

After My Car Crash, I Crawled to the Door My Parents Laughed Stepped Over Me to Leave for Dinner …

At The Bank, My Dad Tried To Make Me Sign Everything Away, But Manager Read The Note I Hide. CH2

At The Bank, My Dad Tried To Make Me Sign Everything Away, But Manager Read The Note I Hide …

My Son Pushed Me at the Mother’s Day Dinner: “That Seat’s for My Mother-in-Law—Get Out.” So I Did… CH2

My Son Pushed Me at the Mother’s Day Dinner: “That Seat’s for My Mother-in-Law—Get Out.” So I Did… Part…

Dad Gave My College Fund to My Stepbrother’s Startup – The Email I Forwarded Changed Everything. CH2

Dad Gave My College Fund to My Stepbrother’s Startup – The Email I Forwarded Changed Everything Part 1 “Your…

End of content

No more pages to load