My Sister Smirked at My Birthday Brunch: “Oh, I Had Lunch with Your Fiancé Yesterday!”

Part One

I used to joke that my sister, Ivy, could turn a sunrise into a spotlight if you gave her five minutes and the hint of an audience. I should have known better than to schedule my birthday at 10 a.m. in a café with floor-to-ceiling windows.

The server had just set down my cortado when Ivy pitched forward with a gasp that would’ve rated a standing ovation on Broadway. She clutched her ankle and went sprawling so dramatically a woman at the next table reached out as if she could catch her mid-fall.

“Ivy!” Mom was up in a heartbeat, napkin in one hand, alarm ringing in her voice. “Those delicate ankles—ever since your dancing days—”

Her “dancing days” were three months of ballet lessons when we were twelve and fourteen, which Dad had paid for by selling a fishing reel he loved. The story had been lacquered and displayed ever since.

“I didn’t even touch her,” I said, too quickly and too quiet and exactly how a guilty person would sound, which made it worse.

“Girls,” Dad said without looking up from his phone, “not today.”

He had been saying not today for 28 years.

The server hurried over with an ice pack; Ivy took it with a tight little smile and a whimper, and then—like a magician who has drawn enough eyes with the first trick—sat up, crossed ankles under her as if she’d learned the fall from a manual, and looked around to be sure everyone had seen.

“It’s okay,” she said to the room. “I’m okay. I just wanted to hug my birthday girl and—” here she winced and put a hand to her throat “—she’s stronger than she looks.”

“She tripped,” I said. “On the rug.”

Mom shot me the kind of look that had made me stop talking when I was five and had nothing to do with rugs. “Eden,” she murmured, “you know your sister’s ankles.”

Grandma Mabel, seated next to me, reached under the table and wrapped her fingers around mine. She didn’t say anything. She didn’t need to. Her squeeze meant I saw.

“Let’s order?” she said out loud, in her I-run-a-community-garden voice that makes grown men put down hedge trimmers. “I hear the blueberry pancakes here are transported down from heaven between two angels.”

We ordered. The crisis turned into a story. The gifts on the windowsill remained wrapped. My best friend, Naomi, who had driven two hours to be here and wore boots that said unapologetic, leaned in. “You want me to accidentally drop my mimosa on her white dress?” she whispered. “I can do a very sincere sorry face.”

“Don’t tempt me,” I whispered back, and found my smile in the bottom of my cup.

When the server left with our order, Ivy straightened, dabbed at an imaginary tear in her mascara, and glanced at each of us in turn as if checking for the lights, camera, action. Then she clapped her hands very softly and said, “Oh! I almost forgot.”

It was the tone you use when you “forget” to bring a celebrity to your office.

“I had lunch with Ethan yesterday.”

The café dropped four degrees. She looked at me while she said it and smiled. Not the world-facing smile. The one that meant checkmate.

My fiancé had texted me yesterday that he was working late. “What,” I said, and it came out never-mind light. “What did you two talk about?”

“Oh, wedding things,” she said, twirling her hair and studying her reflection in a spoon. “He had some concerns. But this is your day.” She lifted her cup to me. “Happy birthday, baby sister.”

Mabel’s hand tightened on mine. I was suddenly aware of everyone in the room touching something—a napkin, a cup, a phone, a person—like we needed proof we were still there.

“Want me to key his car?” Naomi whispered. “I have a fork and poor impulse control.”

“Not yet,” I said, and it surprised me how steady I sounded. “Let me see if there are any keys worth hitting.”

Christmas at the Hale house always looked like a catalog if you squinted. If you looked closely, you saw glue and tape and me holding the corners.

This year, the ceramic reindeer Mom insisted on dusting individually every December stood in their flock on the sideboard. Ivy wore a red sweater with a bow on one shoulder big enough to have its own address. Dad sat in his classic armchair scrolling with his thumb doing that thing men do where they pretend their posture is rest.

“Eden?” Mom leaned into the kitchen doorway, flour on one cheek like a sacrament. Ivy stood behind her, matching apron and mission. “Can you stir the caramel? Ivy and I are handling the cookies.”

“Actually,” I said without moving, “I still need to wrap a few things.”

Her disappointment was polite and weaponized. “Oh. Well. We’ll manage.”

I retreated to the guest room—the one that used to be mine before everything I owned was boxed up so Ivy could have a “meditation room” she never used because silence made her nervous. The lavender candle on her altar had gone from calming to cloying.

A knock tapped the door. “Still have that sixth sense,” Grandma said when I opened it. She came in with a half smile and a whole hug. “Want help with anything that’s not caramel?”

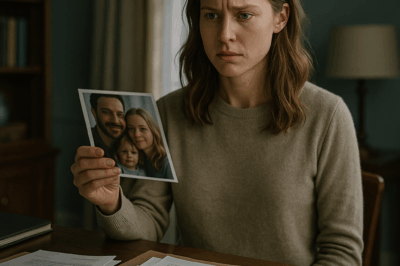

“Can you help me not throw up?” I asked, and showed her the Instagram post I’d been staring at so hard I had memorized the water stains on the table behind it. Ethan at a restaurant I couldn’t afford, timestamped during his “late night.” In the blurry background, a red coat I would have recognized in a blackout.

Grandma’s eyes sharpened the way they did when a squirrel got too interested in the baby lettuces. “Have you asked him?”

“He said he was working. Christmas shopping,” I added, because I didn’t want to sound delusional and I did anyway.

“That boy never could lie worth a bean,” she said, and sat on the bed as if we had all the time in the world. After a moment, she reached into her purse and pulled out an envelope. “I was going to wait until tomorrow,” she murmured. “But I think you need this now.”

The check made my chest lurch. “You can’t—”

“I can, and you will,” she said in the tone that made city council members straighten their ties. “I’ve watched you dim and smooth yourself into a nice flat surface for years so nobody has to see their own reflection. Peace bought with yourself isn’t peace.”

“I—” I began. A shout floated up the stairs. “Present time!”

We walked downstairs to find Ivy cross-legged by the tree among precisely coordinated boxes like an Instagram fairy had been paid overtime. “Mom, Dad, these are for you,” she sang.

Mom unwrapped a bag she had mentioned in passing so many times I had named it in my head. Dad unwrapped a first edition of his favorite book. The handmade photo album and vintage fishing lure I had hunted down with love and luck felt shabby in my lap. This is what war looks like within a family: the receipts are lovely.

“Eden’s turn,” Ivy trilled, handing me a small box with a bow that had more personality than some people we’re related to.

Inside: Finding Your Path: A Guide for Lost Souls.

“I thought you could use it,” she said sweetly. “With all the wedding stress.”

“I—thanks,” I said, just as Ethan checked his phone like it might tell him who he was.

“Oh!” Ivy clapped her hands again. “That reminds me—Ethan and I had lunch yesterday. Centerpieces, Mom. You’ll love this—a cascade of baby’s breath like a cloud—”

“Our lunch?” Mom asked, too casually. “Yesterday?”

“When we ran into each other downtown,” Ivy said smoothly.

On Ethan’s screen, his reflection stared back. Pale.

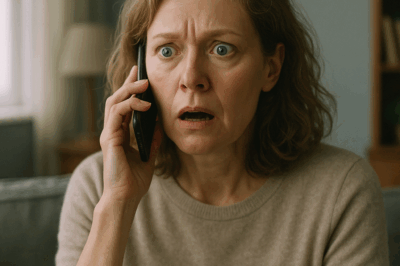

My phone buzzed. Noah: Call me now. You need to see something.

“Excuse me,” I said to the room and walked out. In the hallway, I answered like the house was my body and this was my heart admitting it was bleeding.

“Eden,” Noah said over café clatter, “I shouldn’t have done it, but I did it anyway. Ethan has a rewards account at the Rosewood. He’s been there three times in a month. There’s more—my friend at the desk says he’s been meeting a woman with long red hair.”

The breath I took tasted chemical.

“Do you want me to—”

“No,” I said. “Thank you.”

The bathroom door opened a crack. Ivy slipped in like a gossip had invented a door for her. “You’ve been up here a long time. Everything okay, sis?”

“How long,” I asked, “have you been sleeping with my fiancé?”

She blinked and then smiled like a cat that had discovered how satisfying it is to knock a glass from a counter. “I don’t know what you mean. Is this about lunch? You always had such… trust issues.”

“Stop,” I said. “Stop lying. Just for once. For once in your life.”

A heartbeat where her eyes were a different person’s. Then the smile again, the one with a knife in it. “You want the truth? Fine. Yes. He came to me. He said he was tired of being known as ‘Eden’s fiancé.’ Poor man. We have energy, you and I. Only one of us knows how to use it.”

“You couldn’t let me have one thing,” I said. “You have taken my birthdays, my space, my—”

“One thing?” She laughed, brittle. “You got everything. Grandma’s attention. Dad’s pride when you got into college. Mom’s worry when you moved away. I stood here and learned to rearrange myself around whatever version of you they applauded.”

“Truth has feet,” Grandma likes to say. “It stands up when it’s ready.” Her footsteps might have been what broke us from that interval. “Girls?” she called from the bottom of the stairs. “Cookie’s done!”

Ethan’s knock—soft, uncertain—came at the bathroom door. “Your mom wants you both. Dinner’s ready.”

Ivy put her hand on the knob and her mouth near my ear. “Don’t make a scene. It’s Christmas.”

I opened the door. “Oh, I’m done making scenes,” I said. “I’m going to make an announcement.”

We went down into the light together and took different sides.

“Before we sit,” I said to the table, and looked at each of them in turn. Mom. Dad. Ivy. Ethan. Grandma, her hands folded as if prayer might finally be answered by the right verb. “I have news.”

The words I wanted to say—my sister has been sleeping with my fiancé—were right there. I didn’t say them. There are laws and then there is timing. I swallowed the blood back into my mouth.

“I’m going back to school,” I said. “And I’m going alone.”

Ivy’s smile sputtered. Ethan blinked. Mom’s hand tightened in the crisp cloth beside her plate. Dad’s phone slid, face down, sound off.

Grandma’s eyes creased at the corners with something that might have been pride.

This wasn’t revenge. Not yet. It was the first fence I’d put around myself in years. It would hold long enough to plant something.

Part Two

Three months into my return to campus—business law, coffee, a roommate who studied while she slept because she was twenty and wrong about what her body could do—I learned Ivy and Ethan were engaged from a local magazine that called them “a power couple with flair.” I learned it from the paper rather than the family group text. The headline might as well have read: We devised this to be seen by you.

I did not throw the magazine in the recycling. I put it in a folder labeled Evidence. Later, I would have to make peace with what that said about me. For now, it kept my hands from doing other things.

A push notification pinged on my bus ride home: City announces possible sale of community garden land for development. The photo was of the place Grandma had built with volunteers and stubbornness: rows of vegetables, a greenhouse we’d patched three times after storms, a picnic table she pretended not to cry on once when a grant came through. The quote below the picture was Ivy’s.

“This development will bring jobs and modern housing to our neighborhood,” she said. “The garden is… charming. But it serves a small number of people.”

I got off at the next stop and walked the rest of the way with my hands in fists. When I got to the garden, Grandma was already there—the slow careful steps of someone after a diagnosis. She perched on the bench near the herbs. Her breath was a little winded. When she looked up at me, resolve steadied it.

“The council will listen if we’re loud,” she said. “I have papers. I have people. I have a letter of the law and worse things, if we need them.”

“Define ‘worse things,’” I said, and she handed me a folder in her spidery hand. Some of it was tax stuff. Some of it was volunteer logs and numbers. Some of it were printed screenshots: Ivy’s emails to council members with subject lines like a friend and a favor.

“Remember,” Grandma said, patting the folder, “we plant in rows. We weed in order. We harvest together.”

The council meeting was full of men in good jackets and women with their keys on the table, ready. Ivy had her hair down and her red coat draped beside her chair like an illusionist’s cape.

She said her lines. I said mine. Someone clapped in the wrong place. The chair of the council looked at the paperwork and then looked at Grandma, who looked back like a woman who had eaten respectable men for breakfast twice a year for fifty years.

When it ended, the garden was zoned as protected space with a clause so sharp anyone who tried to argue with it later cut their tongue.

“Not bad,” Noah said next to me, and I realised I’d been holding his sleeve like a UK plug in a US outlet.

I smiled for the first time that day. “Not done.”

Two weeks later, Ivy mailed invitations. The wedding was scheduled for the same weekend as the Festival and the resolution that had dried the ink on our protection. She asked me to be her maid of honor because she is a comedian who only sometimes knows it. “It will prove to people we are not ridiculous,” she wrote in a card shaped like a champagne bottle. “Family First.”

I threw up, then I accepted. Never let someone tell your story for you.

Grandma was worse by then. She had taken to liking ice cream at two a.m. and watching me sleep in a chair beside her. “You’ll need this,” she said one night, handing me a letter with the lawyer’s name at the top. “Not for the garden. For you.”

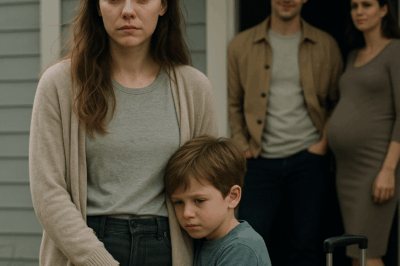

When she died, three days after the council meeting, it felt like the ground had tilted on a hinge I hadn’t realized existed. The morning of the will reading, people hugged me with their eyes and made casseroles I didn’t eat and looked at Ivy like she had ever done anything differently than she had done before. They didn’t know the power in a story until you let it lift something heavy.

Grandma’s recorded message began with a joke, because of course it did. Then it turned to the thing she had always cared about more than manners. “My garden wasn’t carrots,” she said on the screen. “It was choices.”

She left me the trust. Not money that you can spend until it turns into something else. Money with obligation attached. Money that says: this is not yours, this is ours. Ivy sputtered standing up—“You can’t—” and the lawyer handed her a packet with time-stamped photos of her in the greenhouse at midnight with a shredder. I had picked up the pieces she’d left behind and taped them together with law and love. I did not smile because this was not a smile moment.

“Ivy,” the lawyer said with a professional kindness that made me want to hire him for all things forever, “there is photo and video evidence of you attempting to fabricate mental incompetence. If you say another word, it will be to a judge with a very dull pen.”

She sat. I stood with the papers heavy in my hand and the garden heavier in my head and said the thing that wanted to be said.

“Grandma left something to you too,” I told my sister. “Not the garden. A job. The education program needs a director. It needs someone with charisma who knows how to hold kids’ attention and funders’ checkbooks. Someone who understands that being seen isn’t the same as being loved. The pay is honest. The hours are many. The power is different than the one you know.”

“You’re offering me a job?” she whispered, incredulous and outraged and terrified and, somewhere behind all that, moved.

“You wanted to stand where people could see you,” I said. “Stand where it matters.”

She looked out the window as if she’d never seen outside. The garden volunteers were setting up straw bales and banners. The greenhouse had a new pane of glass. For the first time in thirty years, our family was in a room while something larger than us happened outside that had nothing to do with us and everything to do with us.

“Ethan left,” she said abruptly, not turning back. “After the wedding. He said I was willing to betray anyone.”

“You are,” I said. “So was he. You make a good pair. You could both learn a different verb.”

She laughed through her nose and wiped her eyes and took the folder from my hand with a grip steadier than mine had been when I first touched it.

The Harvest Festival that weekend felt like a balm. Mabel’s picture hung on the side of the greenhouse with a frame around it made of dried lavender with tied string. Children ran in the rows where she had once taught me to deadhead marigolds because they protect tomatoes if you let them. The face painting line made its own rules. Someone’s dog taught itself to dig up carrots.

Ivy stood at the education table and showed a group of small hands how to hold a trowel. She didn’t do a voice. She didn’t do a laugh. The kids looked at her like she had something to say and she said it. That’s when I believed this might not just be a plot twist. It might be a different story.

A year later, the garden looked like it had always looked and more. The greenhouse roof gleamed with new dismissible of ice storms. The sign out front said “Mabel’s” now, and before anyone could argue that it was too sentimental, the city council named the street after her and then we all had to rest.

I stood with a clipboard in the education shed while the Tuesday homeschoolers learned that seeds are designed to come apart and hold together and if that doesn’t teach you something about life, you’re not listening.

Mom hovered near the herb bed like it might collapse without her approval. She had come a long way. So had Dad. So had the cat he pretended not to like that still followed him to the car every time.

“We wanted to ask you something,” she said, twisting her wedding ring and not trying to manipulate me, which was the earliest miracle I had learned to trust. “If… if Sunday dinners were here… would you come?”

“This is always open,” I said. “That’s the point.”

She nodded. She didn’t cry. She looked at the lemon balm with the expression of someone about to cultivate humility.

Ivy came out of the greenhouse wiping soil from her hands. “We need more glitter,” she announced. “The butterflies aren’t reading the memo.”

“You don’t need glitter for butterflies,” I said.

“I do,” she said, then looked embarrassed. “For the posters.”

A lot had changed. Some things hadn’t.

That afternoon we planted a cherry tree in the patch Grandma had always pretended was too shady for anything. “For weddings,” someone said, and ten people looked at me. I rolled my eyes and then smiled at nothing. “For graduations,” I said, and it turned out we could let a moment have more than one meaning.

Before I left, I went into the greenhouse alone and pressed my palm against the pane Grandma had changed the most. It was the one by the potting bench where she had made me plant marigolds when I was sullen and seventeen and thought everything had already happened. My hand print looked like the size it had been then. That pleased me more than it should have.

Noah came in with two thermoses and a look on his face like hope is heavy and good. “Tea,” he said. “No literal shovels to give you this time.”

“I think she’d approve,” I said. “Of the tea. Of the tree. Of the way we define family now.”

“Of you,” he said.

It was raining.

We stood under glass.

Seeds remember, Grandma used to say, long after the wind is done. They know what they are when you give them ground.

END!

News

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted ‘I’m pregnant with his child!’. CH2

My husband suddenly passed away. During his funeral, a woman shouted “I’m pregnant with his child!” Part One It was…

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”. CH2

My husband and I divorced 10 years ago. One day, he called me and said, “Get out of the house!”…

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kick me and our child out. Little did he know… CH2

My ex-husband who got his affair partner pregnant kicked me and our child out. Little did he know… Part One…

My husband’s study shocked me – pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately. CH2

My husband’s study shocked me — pictures of mistress & child, divorce papers! I filed it immediately Part One My…

They warned me not to go out after dark. Now I understand why.. CH2

Part 1 Growing up, I always heard the same warning: “Don’t go out late, it’s not safe.” Especially if you’re…

My Brother’s Wedding Was Perfect, Until My “Lost” Invitation Led to an Unexpected Surprise. CH2

Part 1 The worst part about being forgotten is pretending it doesn’t hurt. I stared at my phone, reading the…

End of content

No more pages to load