On my birthday, my sister smashed the cake into my face—and everyone said it was just a joke. I tried to believe them, until the ER doctor saw my X-ray and uncovered a shocking truth.

Part 1

I knew birthdays could be messy, but I never expected mine to end with my sister’s hands on the back of my head and a cake smashing into my face hard enough to tilt the world sideways.

One moment, I was leaning toward the candles, the room glowing with warm, flattering light, everyone’s phones out, counting down. The next, something slammed into the base of my skull, my face plunged forward, and frosting, sugar, and pain exploded all at once.

Laughter erupted. Not the warm, affectionate kind that wraps around you on cue. Sharper. Meaner. More amused than concerned.

“Oh my God, Rowan!” someone gasped, but it sounded delighted, not horrified.

I tried to lift my head. Buttercream clogged my nose. My eyes stung. Underneath the sweetness, I tasted something metallic, copper and salt.

Blood.

The edges of the cake pan dug into my ribs as I slid sideways off the chair. The floor rushed up, and my left temple bounced off it, a second, smaller impact that sent bright white sparks racing across my vision.

Somewhere above me, my sister’s laugh pealed out, bright and crisp, the sound of someone who’d nailed the punchline exactly the way she’d wanted to.

“Relax,” she said between giggles. “It’s a TikTok trend, Mom. Cake smash! She’s fine. Aren’t you, Ave?”

Hands hovered near me but didn’t touch. Camera flashes continued, phones still recording. Everyone wanted content. No one wanted responsibility.

I wiped at my eyes, smearing frosting and tears. The room throbbed in blue and white pulses. My head felt like it had been cracked open and then stuffed with cotton.

“I’m fine,” I tried to say, but it came out thick.

“You’re such a good sport,” Mom cooed, relief already edging into annoyance. “Come on, Avery, get up. You’re making everyone nervous.”

Of course I was the problem.

Of course.

I pushed myself upright. The room tilted. For a second, I thought I might throw up on the centerpiece. The headache that had started as a dull throb in the back of my skull sharpened into something mean, spiking behind my left eye.

Rowan thrust a napkin at me, grinning. “Lighten up,” she said, dabbing at my cheek while making sure everyone could see her being so helpful. “You should’ve seen your face.”

I had. From behind my own eyes.

Shock. Then humiliation. Then that familiar, heavy resignation.

Avery is strong. She can handle herself.

Mom’s favorite line echoed in my head, even as my neck screamed when I turned it.

I was not strong.

I was thirty-six years old, bleeding into a birthday cake in my mother’s dining room while my little sister performed.

From the outside, we looked like a normal family.

There were fairy lights strung along the mantle. A banner that read HAPPY BIRTHDAY, AVERY in glittery letters hung above the sliding glass door. The long oak table was set with the good dishes. A candle in the shape of the number 3 and another in the shape of the number 6 stood lopsided on the ruined cake, their flames flickering bravely above the frosting crater my face had left.

If you didn’t know us, you’d think: how sweet. They really went all out.

If you grew up inside these walls, you’d see the truth.

My sister Rowan, two chairs down, basking in the attention. My mother, Marlene, occupying the “Queen’s seat” at the head of the table, tight smile smoothing over any awkwardness before it could fully form. Her husband—my stepfather—Gerald, laughing a little too loudly, eyes darting to Mom for cues.

And me.

Avery. The quiet one. The reliable one. The daughter who didn’t “need” attention because, as Mom liked to remind everyone, “Avery is strong. She can handle herself.”

What she meant was simpler: Rowan needed the spotlight. I needed to get out of the way of it.

Rowan was born eighteen months after me, but you would never know I came first. In our house, she was the sun, and we were all expected to orbit just right to avoid flares.

She had a kind of presence that swallowed space. Loud, funny, dramatic. A natural performer. Teachers adored her. Boys lined up for her. Mom glowed when she walked into a room.

When I walked in, Mom’s face softened politely, like she’d just remembered there was a second daughter and it would be rude not to acknowledge her.

I learned early that Rowan’s moods dictated the temperature of the entire house. If she was happy, Mom baked cookies and hummed along to the radio. If she was sulking, everyone got quiet, careful, bent around her.

And me? I learned to fit myself into whatever cracks were left.

I swallowed small hurts. The way Rowan “accidentally” bumped me into the coffee table when we were ten, then laughed when I cried. The way she whispered “clumsy” when I tripped down the stairs in high school. The way she insisted on taking my gym bag “to help” and somehow my clothes ended up all over the locker room.

“Avery, don’t be dramatic,” Mom would say every time. “Your sister loves you. You know how she is. She didn’t mean it.”

If I protested too much, Mom’s eyes would go cold. “Don’t start,” she’d say. “You’re the older one. Set an example.”

So I stopped asking for help.

I got a job in high school. Saved for college on my own. Studied late while Rowan hosted impromptu parties in the living room. I moved out the week after graduation, renting a tiny studio in Seattle, trading one kind of noise for another.

I built a life—small but mine. I worked my way up from receptionist to project manager to operations director at a digital marketing firm. I bought secondhand furniture and proudly paid my own bills.

I also kept answering my phone whenever “Mom” lit up the screen.

Rowan’s car payment was late. Could I help?

Rowan needed a place to stay “just for a few weeks” after a breakup. Could she crash with me?

Rowan was upset because I hadn’t come home for Easter. Could I smooth things over?

“Avery is strong,” Mom would say, voice threaded with guilt and expectation. “She can handle it.”

So I handled it.

Until I didn’t.

The night of my thirty-sixth birthday, even as sugar crusted on my skin and blood trickled warm down the back of my neck, part of me still tried to rewrite reality.

Maybe Rowan had pushed too hard by accident.

Maybe the angle of my chair had been wrong.

Maybe the ringing in my ears and the white flares eating at the edges of my vision were just… adrenaline.

“It’s just a joke,” Gerald said from somewhere behind me, his chuckle shaky. “You girls and your pranks. You’ll laugh about this someday.”

The room wobbled around the edges. I pushed my chair back, the legs scraping loudly. A smear of red and white marked the hardwood where my head had been.

My aunt Elise, Mom’s younger sister, stood in the doorway to the kitchen, dish towel in hand. For a moment, her face looked wrong—eyes wide, lips pressed together, knuckles white on the towel.

Then she caught Mom’s gaze, and her expression smoothed out.

“Maybe Avery should sit down,” she suggested.

“I am sitting,” I muttered, blinking hard.

Rowan rolled her eyes. “Oh my God, you’re fine,” she said. “Seriously, you barely hit the floor. Don’t make this weird.”

Don’t make this weird.

Translation: Don’t make us look at what we just saw.

I dabbed at my neck with a napkin. It came away pink.

“It’s fine,” I echoed. Because that was my line. My role. The quiet one. The steady one. The daughter who didn’t need attention.

We went through the rest of dinner on autopilot. Gifts. Small talk. Cake salvaged around the crater and scooped into bowls.

By the time I pulled my coat on, the pounding in my head had settled into a steady, vicious throb, like someone had set up a construction crew at the base of my skull and told them to get to work.

“Text me when you get home,” Mom said in the doorway, hugging Rowan from behind, not me. “You know how she worries,” she added to my sister, as if I weren’t standing right there.

Rowan smirked. “You gonna sue me if you find a crumb up your nose later?” she teased.

I forced a smile. “I’ll send you the bill,” I said.

The night air hit my face like a slap. I walked to my car, keys digging into my palm, the world swimming slightly with each step.

I drove home anyway.

Calling anyone felt worse.

I could already hear Mom’s voice if I asked for a ride to the ER.

You don’t need a doctor. You bruise easily. Stop making a scene.

And Rowan would laugh. That light, dismissive sound that always made me feel smaller than I already did.

So I went alone.

Back in my small apartment, I peeled off my frosting-stiff shirt and stood under the shower until the water ran clear. The hot spray beat against the sore spot behind my left ear; pain flared, hot and sharp.

I stumbled out, wrapped myself in a towel, and caught sight of my reflection.

A bruised shadow bloomed behind my ear, ugly and dark. My eyes looked too bright. My skin looked too pale.

I crawled into bed and lay staring at the ceiling, the room slowly spinning.

Every heartbeat was a hammer against my skull. Light from the streetlamps outside seeped through the blinds, slicing my vision into painful stripes.

It’s fine, I told myself. You just hit the floor weird. Concussions happen. People rest. They get better.

Somewhere beneath that, a smaller voice whispered: Something is wrong.

I fell asleep in fragments, waking in short jolts when a wave of nausea rolled over me or when my head pounded hard enough to punch through whatever thin layer of sleep I’d managed.

By morning, the headache hadn’t eased. It had sharpened into something vicious.

When I swung my legs out of bed, the world lurched. The floor seemed to tilt away from me. My stomach heaved. Bright light knifed behind my eyes.

I pressed my fingers to the tender spot behind my ear.

They came away sticky with dried blood.

That was the moment fear finally made itself impossible to ignore.

I pulled on jeans and a sweatshirt, moving slowly, gripping the wall when the room swayed. I slid my keys into my pocket.

Driving felt reckless.

Not driving felt worse.

The ER was fifteen minutes away.

I’d gone years without needing a hospital.

I had no words for why it felt like walking into a confession booth.

Part 2

Seattle’s ER on a Saturday morning was a symphony of misery.

Coughs. Crying kids. The hiss of oxygen. The sharp scent of antiseptic layered over something sour and human.

I squinted against the overhead lights as I stepped up to the check-in desk.

The nurse glanced up, professional smile already in place. It faltered when she saw me flinch at the brightness.

“What brings you in?” she asked, her voice gentler than her tired eyes.

“I hit my head,” I said. “Last night.”

“How?” she asked, fingers poised over the keyboard.

“My sister… shoved my face into a cake,” I said.

Her eyebrows lifted, just a fraction. “You passed out?” she asked.

“I don’t think so,” I said. “But everything went… fuzzy. And my head’s been pounding ever since. The light hurts. I feel… off.”

She studied me for a moment, then nodded. “Let’s get you triaged,” she said. “Have a seat. Don’t look at your phone if you can help it. We’ll call you soon.”

Soon turned out to be five minutes.

The triage nurse darkened the lights in the small exam cubicle for me. “On a scale of one to ten, how bad is the pain?” she asked.

“Seven,” I said. “Sometimes eight.”

“Any vomiting?”

“Not yet,” I said. “Just… waves.”

She checked my vitals, then frowned slightly. “You’re a little tachy,” she murmured. “I’ll flag you for imaging.”

She handed me a paper bracelet with my name on it: AVEY DALTON. They had misspelled it. I didn’t correct them.

I sat on a gurney in a curtained-off bay, listening to the ER orchestra around me.

A child down the hall sobbed hiccuping cries. Somewhere, a monitor beeped steadily. A man cursed softly under his breath as someone wrapped his wrist.

I replayed last night in my mind like a movie I was suddenly watching on a bigger screen.

Rowan behind me.

Rowan’s fingers pressing into the back of my head.

Rowan’s eyes, wide and bright and almost… satisfied.

I’d spent years downgrading that look to “playful” or “competitive.”

Now, under fluorescent lights that left nothing soft, the memory didn’t feel like sibling teasing.

It felt like something uglier.

“Ms. Dalton?”

I looked up.

A man in his late forties stood at the foot of the bed, white coat, ID badge, tired but kind eyes. DR. HANLEY, Emergency Medicine.

“Hi,” he said, pulling a stool close. “I’m Dr. Hanley. I hear you had a rough birthday.”

I tried to smile. It came out crooked.

“You could say that,” I murmured.

He went through the motions I’d expected: asking me to follow his finger with my eyes, to squeeze his hands, to touch my nose. He shined a light in each pupil. With every movement, my head throbbed.

“You’re a bit unsteady,” he said. “We’re going to get a CT of your head. Just to be safe.”

The words made my stomach knot.

“Do you think it’s a concussion?” I asked.

He met my gaze. “At minimum,” he said. “Head injuries can be tricky. Sometimes what seems like a minor incident can cause more damage than we’d like. I’d rather be overly cautious than miss something.”

Safe.

It struck me, hearing that word directed at me by someone who wasn’t trying to talk me out of my own concerns.

“When was your last serious injury?” he asked, flipping through the electronic chart.

I hesitated.

“Three years ago,” I said. “I fell down the stairs at my mom’s house. Bruised my ribs. I didn’t go to the hospital.”

“Any other injuries?” he asked. “Broken bones as a kid? Car accidents?”

“Just… normal stuff,” I said. “Lots of ‘clumsy Avery’ moments.”

His eyes flicked up at that.

“Clumsy,” he repeated. “That your word or someone else’s?”

“My sister’s,” I said, before I could stop myself.

He didn’t comment. “Let’s get that scan,” he said.

The imaging room was colder than the ER, the air humming with the low buzz of machinery. I lay flat on the narrow table, the headrest cradling my skull in a way that somehow made it throb more.

“Stay still,” the tech said. “This will be quick.”

I stared at the ceiling, blank and off-white, while the machine slid around my head.

Images of last night flickered.

Rowan’s nails digging into my scalp.

The world flipping.

Mom’s tight smile.

You’re too sensitive. Don’t be dramatic. Your sister loves you.

I thought of three years ago—the staircase, the tumble, the way my ribs had screamed for weeks every time I breathed deeply.

I’d tripped, I’d told myself. That’s all.

Back in the ER bay, I curled onto my side, careful to keep my head still. The curtain rustled. Dr. Hanley reappeared, a tablet in hand.

His face looked different.

Less neutral. More… focused.

“Avery,” he said, pulling the stool close again. “I’ve got your scans.”

He turned the tablet so I could see.

I didn’t understand the grayscale images. Loops and shadows and shapes. But I understood his tone.

“You have a small hairline fracture here,” he said, tapping a faint line along the left side of my skull, just behind the ear. “It’s not displaced, which is good. But it’s real. This wasn’t just a bump. You also have signs of a concussion.”

Fear flared, hot.

“Okay,” I said, throat tight. “So… rest? Painkillers?”

“We’ll talk about management,” he said. “But there’s something else.”

He swiped to another image.

“This,” he said, “is your left ribcage. The scan for your head captured enough of your upper body to notice something I didn’t expect.”

He zoomed in on a curved white bone.

“See this?” he asked. “This slightly rough area here? That’s a healed fracture. Old, but not ancient. Based on the healing pattern, I’d estimate… three years ago.”

My mouth went dry.

“Three years,” I repeated.

Stairs. Eleanor’s funeral. Rowan behind me. My feet slipping, or being pushed—it had always been a blur.

“I–I fell down the stairs,” I said. “They were… steep. I’m clumsy.”

The word sounded wrong in my mouth.

Dr. Hanley watched me.

“Avery,” he said quietly. “Head fracture. Old rib fracture. Multiple reported falls. You say you’re clumsy. Do you drink heavily?”

“No,” I said.

“Any balance disorders? Neurological diagnoses?” he asked.

“No,” I said again.

“Does anyone ever push you?” he asked.

The question landed like a punch.

Images crashed into each other. The coffee table when we were ten. The stairs in high school. The stairs three years ago. The parking lot last year, when Rowan had “jokingly” bumped my shoulder and I’d slipped on gravel, ripping my jeans open at the knee.

The cake.

Her hands.

Her laughter.

“I…” My voice broke. “My sister and I… we joke around. She doesn’t mean—”

He held up a hand. Not to silence me. To slow me down.

“Injuries like this, combined with what you’ve told me, raise concerns,” he said gently. “As your physician, I am a mandated reporter. That means if I suspect someone may be hurting you—especially someone close to you—I am required to report it.”

Report.

A word I’d associated with school bullies and tax fraud.

Not with my family.

He stood, stepping over to the wall phone. He lifted the receiver, punched in a code, his voice low but firm.

“This is Dr. Hanley in the ER,” he said. “I need to initiate a 911 call and an in-hospital report for suspected domestic assault.”

My ears rang.

For me.

When he hung up, he turned back to me, eyes steady.

“Avery,” he said, “someone did this to you.”

For a second, everything inside me revolted.

No. I did this. I’m clumsy. I slip. I bruise easily. I—

Memories shoved back, louder.

Rowan whispering “You’re so dramatic” after every fall.

Mom telling me not to seek medical help because “we can’t afford another bill.”

My own voice minimizing every injury so no one had to feel uncomfortable about the fact that the common denominator was always my sister’s proximity.

“Are you okay?” Dr. Hanley asked.

I shook my head, then regretted it as pain flared. Tears blurred my vision.

“I don’t know,” I whispered. “I don’t know what’s normal anymore.”

He didn’t rush to fill the silence.

“You’re not alone in this,” he said, after a beat. “Someone from law enforcement will come talk to you. You get to decide how much you share. But I want you to hear me clearly: what happened to your head is not ‘just a joke.’”

A soft knock came at the curtain.

A woman stepped in, badge at her hip, hair pulled back, expression composed but kind.

“Avery?” she said. “I’m Detective Carver. Mind if I sit?”

My family was about to become an official police matter.

Part 3

Detective Carver pulled a plastic chair closer to the gurney, sitting so we were at eye level.

“I know this is a lot,” she said. “We can go as slow as you need.”

I nodded, the motion small.

“I’m going to ask some questions,” she continued. “If you don’t want to answer anything, that’s okay. Just tell me. Ready?”

No, I thought.

“Yes,” I said.

“Your doctor told me your head injury happened at a birthday party,” she said. “Tell me about that.”

The story came out in fits and starts.

The candles. The countdown. Rowan behind me. The push. The floor. The laughter.

“So your sister shoved your head into the cake?” Carver clarified.

“Yes,” I said. “She said it was a… trend. A joke.”

“Did she warn you?” Carver asked.

“No,” I said. “I didn’t even know she was behind me until… she was.”

“Did you hit the table or the floor first?” she asked.

“The cake pan,” I said. “Then the floor. My head bounced.”

She scribbled in her notebook.

“Has your sister ever… done anything like this before?” she asked.

The word “like” did a lot of heavy lifting.

“There were accidents,” I said. “Falls. Bumps. We roughhoused as kids.”

“Can you give me examples?” she asked.

The coffee table. The stairs. The parking lot.

I told her about being ten, about playing tag in the living room, about Rowan “misjudging” a shove and sending me flying into the table edge. About Mom scolding me for crying loud enough to “make a scene.”

I told her about the staircase fall in high school, Rowan directly behind me, hand flat against my back as I suddenly lost my footing.

“You never saw her push you?” Carver asked.

“It happened fast,” I said. “She was close. Then I was falling.”

I told her about the fall three years ago, after my great-aunt Eleanor’s funeral. The Victorian house I’d inherited—unexpected, undeserved, according to Mom. The way Rowan’s face had gone cold when the will was read.

“A Victorian house?” Carver asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “My aunt didn’t have kids. She left it to me. Rowan was… not thrilled.”

Understatement of the decade.

That night, walking up the stairs at Mom’s, still in my black dress, my mind full of probate logistics, I’d felt fingers on my back. A little harder than a nudge. More like a jab.

Then my foot slipped.

I’d tumbled down half a flight, slamming my side into the railing. The pain in my ribs had stolen my breath.

“You’re so dramatic,” Rowan had laughed afterward, pressing a bag of frozen peas to my bruised skin. “You tripped. Don’t go making it into some Lifetime movie.”

“She insisted I didn’t need a hospital,” I told Carver. “Said medical bills would just stress Mom out more. I believed her.”

“Has anyone ever told you not to seek medical care after getting hurt?” Carver asked.

“Every time,” I said. “Rowan. Sometimes Mom. They said I bruise easily. That I’m sensitive. That I overreact.”

I heard how it sounded as I said it.

Carver’s eyes softened.

“Avery,” she said quietly, “has your sister ever hurt anyone else? Broken things? Lost control?”

On some level I knew the answer.

I thought of Rowan’s boyfriends, all of whom seemed dazzled and drained in equal measure. The smashed picture frame after one of her breakups, the dent in Mom’s car door that had appeared after Rowan “misjudged the garage.”

“I’ve seen her throw things,” I said. “She gets… intense. But she’s very good at apologizing. At making it sound like… passion.”

“And your mother?” Carver asked. “How does she react?”

“She… smooths it over,” I said. “She always has. ‘Rowan’s just expressive.’ ‘Rowan doesn’t mean it.’ ‘Don’t provoke your sister, Avery.’”

Carver wrote for a moment, then looked up.

“The pattern your doctor and I are seeing,” she said, “combined with what you’re telling me, suggests something called coercive control and physical abuse. It doesn’t always look like what people picture when they hear those words. It can look exactly like what you’re describing—one person repeatedly ‘joking’ or ‘accidentally’ hurting another, then controlling the narrative around it.”

Abuse.

The word sat on the air between us.

“For what it’s worth,” Carver added, “I’ve worked a lot of these cases. You’re not overreacting. You’re not crazy. You’ve been conditioned to doubt your own experience.”

A lump formed in my throat.

Before I could respond, the curtain jerked open.

“Avery Lynn Dalton, what on earth are you telling these people?”

My mother swept in like a storm in heels and perfume, Gerald right behind her, his expression a mix of worry and irritation.

Her lipstick was perfect. Her hair was set. She’d had time to get ready before coming here.

“Mrs. Dalton,” Carver said, standing. “I’m Detective Carver. We’re in the middle of—”

“I don’t care what you’re in the middle of,” Mom snapped. “My daughter hit her head during a birthday joke, and now you’re making it into some criminal investigation? This is absurd.”

She turned to me, eyes blazing.

“A fracture?” she demanded. “From frosting? Avery, tell them you’re confused. You bruise easily. You’ve always been sensitive.”

Sensitive. Dramatic. Overreacting.

My greatest hits.

Dr. Hanley appeared at the edge of the curtain, posture calm but firm. “Mrs. Dalton,” he said, “your daughter has a hairline skull fracture and a documented older rib fracture. These aren’t bruises. This is serious.”

Mom’s eyes slid past him like he hadn’t spoken.

“Avery,” she said again, voice dropping into the dangerous softness I recognized from childhood. “Look at me. This is getting out of hand.”

I did look at her.

For the first time, I didn’t see the woman I spent my life trying to impress. I saw the woman who had spent decades choosing one daughter’s version of events over the other’s, because one was easier to adore.

“I’m not confused,” I said.

Silence dropped like a curtain.

Mom blinked. “Excuse me?”

“I’m not confused,” I repeated. My voice shook, but the words themselves felt solid. “I’m hurt. I’m scared. And I’m not going to pretend it’s fine so you can feel comfortable.”

Her face hardened.

“You are turning on your own sister,” she hissed. “After all she’s done for you—”

“What she’s done is push me down stairs and into furniture and last night into a cake hard enough to fracture my skull,” I cut in. “You just never wanted to see it.”

Gerald shifted, eyes flicking between us. “Marlene,” he started, “maybe we should—”

“Don’t,” she snapped at him, then whirled on Carver. “This is a family matter. We’ll handle it. You’ve got addicts and criminals out there; you don’t need to waste resources on a clumsy woman and a sister who plays too rough.”

Carver’s jaw tightened.

“Mrs. Dalton,” she said evenly, “head fractures and coerced medical avoidance are not ‘family matters.’ They are crimes.”

Mom went pale, then flushed.

“Avery,” she said, her voice trembling with outrage and something almost like fear. “Tell them to stop. Right now.”

For thirty-six years, my reflex had been to make her feel better.

To soothe. To soften. To swallow my own pain so hers wouldn’t spike.

For the first time, I didn’t.

“I want to continue,” I told Carver, not breaking eye contact with my mother.

Mom stared at me like she’d never seen me before.

Carver nodded once. “Mrs. Dalton, Mr. Dalton,” she said. “I need you to step outside while I finish speaking with Avery. This is standard.”

Mom opened her mouth.

“You can wait in the family room,” Dr. Hanley added, his tone leaving no room for argument. “We’ll update you when we’re done.”

For a moment, I thought Mom might refuse. That she’d dig in her heels and demand to stay.

Then she spun on her heel, hair swinging, and stalked out, Gerald trailing behind, his shoulders slumped.

The curtain fell back into place. The room felt bigger.

Lighter.

Like someone had cracked a window in a house that had been sealed for years.

Carver sat again.

“Avery,” she said quietly. “Thank you.”

“For what?” I asked, dazed.

“For not backing down,” she said. “That was… brave.”

It didn’t feel brave. It felt like jumping off a cliff with no guarantee there was water below.

A figure hovered at the curtain, then cleared her throat softly.

“Um… Detective? Avery?”

My aunt Elise peeked in, eyes red, shoulders hunched as if she expected to be yelled at for stepping into the wrong room.

“Come in,” Carver said.

Elise moved closer, wringing her hands.

“I should have come sooner,” she whispered to me. “I tried calling you last night, but your phone went to voicemail, and I… I had this feeling.”

She glanced at Carver. “I have information,” she said. “About Rowan. About… this.”

Carver gestured to the chair beside her. “Please,” she said. “Sit.”

Elise lowered herself into the seat like her knees might give out.

“When the girls were little,” she began, “there were… moments. Things I saw that didn’t sit right.”

I gripped the blanket tighter.

“I told myself it was sibling rivalry,” she went on. “Kids being kids. But as they got older, it changed. Rowan changed. She got… sharper.”

She swallowed.

“I saw her push Avery on the stairs once,” she said. “Avery was twelve. Everyone thought she slipped. But I was at the top of the landing. Rowan’s hand was flat on her back. It wasn’t a nudge. It was a shove.”

My stomach dropped.

No one had ever said that out loud before. Not like that. Not as fact.

“I tried to say something,” Elise whispered. “Marlene shut me down. She said I was overreacting, that I was trying to cause drama. She threatened to stop inviting me over if I ‘kept stirring things up.’”

She stared at her hands.

“I backed off,” she said. “I told myself I’d imagined it.”

Her voice broke. “I’m so sorry, Avery.”

A lump rose in my throat.

“That’s not all,” she added. “Three years ago, after Eleanor’s funeral… I overheard Rowan on the phone. She was furious about the Victorian house. She said something like, ‘If Avery wasn’t so damn competent, she’d be the one needing help and I’d be the one managing everything.’ Then… she said, ‘Accidents happen. Maybe she’ll get a reality check.’”

The room went very still.

Carver’s pen stopped moving.

“Do you remember the staircase fall?” Elise asked me, eyes shining. “That same night?”

I nodded slowly, the memory suddenly shoving its way to the front of my mind. Rowan behind me. A jab between my shoulder blades. The air disappearing from my lungs as I went down.

“Yeah,” I said. My voice sounded like it belonged to someone else. “I remember.”

Elise covered her mouth with her hand. “I should have put it together sooner,” she said. “I was scared of what Marlene would do if I accused Rowan of… anything. But after last night… I can’t stay quiet anymore.”

Carver exhaled.

“Thank you,” she said. “This helps us a lot. It establishes a pattern.”

“A pattern of what?” I asked, though I knew.

“Of deliberate harm,” Carver said. “Of intent. We’ve already requested the restaurant’s security footage. We’ll be interviewing everyone who was at your birthday. We’re also petitioning for access to Rowan’s phone. The content your aunt overheard suggests we may find more planning.”

Planning.

The room tilted again. This time, it wasn’t the concussion.

Rowan hadn’t just been impulsive.

She might have been incubating this.

For years.

Carver stood.

“For now,” she said, “the most important thing is that you’re not alone. Elise has offered to stay with you?”

“I’m not leaving her,” Elise said fiercely, surprising us both. “Not again.”

I let out a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding.

“Okay,” I said.

Carver gave me a small, real smile. “We’ll be in touch,” she said. “And Avery? Whatever happens next, what’s unfolding here is not your fault.”

I wasn’t sure I believed her.

But for the first time, I wanted to.

Part 4

The next forty-eight hours passed in a blur of ice packs, painkillers, and silence broken only by the soft buzz of my phone.

Aunt Elise settled onto my couch like she’d been rehearsing for it her whole life. She made tea. She reheated soup. She sat with me through the waves of nausea and the pounding behind my eye.

She didn’t ask for details unless I offered them.

She didn’t say, You’re overreacting.

She didn’t say, Your sister loves you.

The absence of those words felt like oxygen.

On the second evening, Detective Carver called.

“We got the footage,” she said.

My hand tightened around the phone.

“And?” I asked.

There was a pause.

“Avery,” she said, “it was deliberate.”

The room seemed to recede a little.

“We watched it several times,” she went on. “Rowan positions herself behind you. She looks over her shoulder, checks where the table is, then puts both hands on the back of your head and pushes—hard. When you hit the floor, there’s a moment—barely a second—where she smiles. Then she starts acting panicked.”

A cold wave washed through me.

I heard my own voice, days earlier, saying Maybe I just slipped. Maybe she didn’t realize how hard she pushed. Maybe—

“Okay,” I said, my voice thin.

“We also have her phone,” Carver continued. “With a warrant. We found notes.”

“Notes?” I repeated.

“Dates and descriptions,” Carver said. “Incidents that line up with what you’ve told us. The coffee table when you were ten. The high school stairs. The fall three years ago. They’re labeled things like ‘Avery stair fall—blame clumsiness’ or ‘Parking lot trip—everyone laughed.’”

Revulsion crawled up my spine.

“In another folder,” Carver added, “we found something labeled ‘Future.’”

My chest tightened.

“What’s in it?” I asked, barely above a whisper.

“Projected opportunities,” she said. “Times she expected you to be vulnerable. Holidays. Family events. Situations where an ‘accident’ would be plausible.”

I closed my eyes.

“So this wasn’t…” My voice failed.

“It wasn’t spontaneous,” Carver said gently. “It was a pattern.”

Elise sat down beside me, her hand finding the middle of my back, steady.

“We’re moving forward with charges,” Carver said. “Assault causing bodily harm. Possibly more, depending on how the DA wants to frame it.”

I swallowed.

“What about… my family?” I asked. “My mom. Gerald.”

“There will be a meeting,” Carver said. “We’re calling everyone together Sunday evening at your parents’ house to formally inform them and serve paperwork. With your consent, we’d like you there.”

“Why?” I asked, my stomach clenching. “Isn’t this about Rowan?”

“It is,” she said. “But it’s also about a dynamic. We want the family to hear the facts all at once. No room for spin. No whispers behind your back about what you did or didn’t say. That transparency can prevent a lot of… rewriting.”

I knew exactly what she meant. I’d grown up in rewrites.

“You won’t have to speak,” she added. “Just… be present. If that feels like too much, say no. But I think having you there, seeing Rowan’s reaction when the evidence is laid out, may give your mother less space to pretend this is all in your head.”

The thought of stepping back into that house made my skin prickle.

But the thought of them having that meeting without me—of Mom hearing only Rowan’s version of events, of my absence being spun as guilt—felt worse.

“I’ll come,” I said.

Sunday arrived faster than it had any right to.

I stood in my childhood bedroom—still intact, still painted the same pale blue Mom had chosen when I was eleven—and stared at myself in the mirror.

The bruise behind my ear had spread into a sickly yellow halo, fading slowly. The headache had dulled but still pulsed faintly, a ghost of itself.

“You don’t have to do this,” Elise said from the doorway.

“I know,” I said. “That’s why I’m doing it.”

She nodded, eyes shining with something like pride.

When we entered the dining room, everyone was already there.

Gerald stood near the sideboard, hands stuffed in his pockets, face drawn. Mom sat at the head of the table, lips pressed into a thin line, eyes flicking over everything like she might rearrange the scene into something more aesthetically pleasing.

Rowan leaned against the far wall, phone in hand, scrolling. She looked up as I walked in.

A slow smirk curved her mouth.

“Oh, look,” she said. “The guest of honor returns. How’s your delicate little head, Ave? Still milking it?”

“Avery,” Mom snapped. “Don’t start anything.”

The deja vu made my chest tighten.

As if I had ever started anything in this house.

A knock sounded at the front door. Three sharp raps.

Everyone froze.

“I’ll get it,” Gerald muttered, gratefully escaping.

Detective Carver stepped into the dining room a moment later, two uniformed officers at her back.

“Ms. Dalton,” she said, nodding to me. “Mr. and Mrs. Dalton. Rowan.”

Mom shot to her feet. “What is this?” she demanded. “I thought you were just… taking statements. This is my home.”

“We’re here as part of an ongoing investigation,” Carver said calmly. “We’ve completed our initial review of the evidence.”

“Evidence?” Rowan scoffed. “Of what? Cake abuse?”

Her laugh sounded brittle.

Carver’s expression didn’t change.

“Rowan Dalton,” she said clearly, “you’re under arrest for assault causing bodily harm and related charges. You have the right to remain silent—”

The room exploded.

“What?” Mom shrieked. “You can’t be serious! This is insane. Say something, Gerald!”

Gerald’s mouth opened and closed, but no sound came out. He sank into a chair, color draining from his face.

Elise stayed beside me, her hand slipping into mine, squeezing once.

Rowan’s mask cracked.

The easy smile evaporated. Her eyes went sharp, darting between me and Carver.

“You’re kidding,” she said, laugh high and strange. “For what? A birthday prank? Avery is just trying to get attention. She’s always been jealous.”

“We have medical imaging showing a skull fracture,” Carver said. “We have video footage clearly showing you pushing her head with enough force to cause that injury. We have notes from your phone documenting previous incidents, including the staircase fall three years ago. And we have evidence you were planning future ‘accidents.’”

She recited it calmly, like a list. Like this was just another Tuesday.

Rowan’s gaze snapped to me, all pretense gone.

“You went through my phone,” she spat.

“I didn’t,” I said quietly. “The police did. With a warrant.”

“You think you’re so perfect,” she hissed. “You think you deserve everything. The job. The house. Eleanor’s stupid Victorian. You think she loved you more? She only picked you because you’re pathetic. Because you needed it more.”

“Rowan,” Mom gasped. “Stop—”

Rowan barreled on, unraveling in real time.

“I’ve cleaned up after her my whole life,” she snarled. “Any time she tripped, any time she made a mess, I was the one who had to make sure she didn’t ruin everything. And everyone acted like I was the difficult one.”

“You shoved her down the stairs,” Elise said, voice shaking. “I saw you.”

Rowan whirled on her. “You keep out of this,” she snapped. “You were never part of this family, no matter how many times you showed up with your sad little store-bought pies—”

“Enough,” Carver said sharply. She nodded to the officers. “Cuff her.”

The uniforms stepped forward.

“Mom!” Rowan screamed as cold metal closed around her wrists. “Tell them! Tell them Avery is exaggerating. Tell them she’s always been dramatic. Tell them I didn’t do anything!”

Mom didn’t move.

Her face had gone the color of copy paper. Her hands trembled on the back of her chair.

“Mom!” Rowan shrieked again, panic rising. “Say it!”

Mom’s lips parted.

For a moment, I thought she might. That she’d slide into her lifelong role, smoothing, denying, rewriting.

Instead, a sound I’d never heard before emerged.

A small, broken whisper.

“Rowan,” she said. “Stop.”

Two syllables.

Stop.

Not Avery, don’t.

Not You’re overreacting.

Just… stop.

Rowan stared at her, stunned.

“Are you seriously—?” she began.

The officers guided her toward the door.

She twisted once more to glare at me.

“You ruined everything the day you were born,” she spat. “You know that? I should’ve—”

The door closed on the rest of whatever she was going to say.

Silence flooded the dining room.

The house felt like it had been shifted onto new foundations in real time.

Mom sank into her chair as if her legs had given out. Gerald put a hand on her shoulder. She didn’t shake it off.

“I’ll be in touch about court dates and protective orders,” Carver said quietly to me. “For now, you’re not to have any contact with Rowan. If she reaches out, let us know.”

I nodded.

Elise squeezed my hand again. Hard enough to hurt, but in a way that made me feel more anchored than damaged.

When the police left, the house exhaled.

Mom stared at the tablecloth, tracing the pattern with shaking fingers.

“I didn’t know,” she whispered.

No one spoke.

“I didn’t want to know,” she corrected herself, voice cracking. “That’s worse.”

I didn’t answer.

Because for once, fixing her feelings wasn’t my job.

Part 5

The legal process was less dramatic than I’d imagined.

There were no packed courtrooms, no weeping juries. No TV-movie speeches.

Just a series of hearings in beige rooms with scuffed floors and buzzing lights, where terms like “assault,” “coercive control,” and “pattern of harm” were said out loud about my sister.

Rowan took a plea deal.

Mandatory therapy. Supervised probation. A five-year protective order preventing her from coming near me, my home, or my workplace. An agreement that any violation would mean jail time.

It wasn’t a grand slam of punishment.

It was quiet. Firm. Real.

Mom barely spoke during the hearings. When the prosecutor described the security footage—Rowan’s angle, her timing, her smile—Mom flinched.

When screenshots of Rowan’s phone notes were entered into evidence, Mom covered her mouth with her hand.

On the third hearing day, during a recess, she approached me in the hallway outside the courtroom.

“Avery,” she said, voice shaking. “Can we… talk?”

We stood by the water fountain, people streaming past, the murmur of other cases echoing down the corridor.

“I spent years telling myself my job was to keep the peace,” she said. “To protect the family. I thought that meant… smoothing things over. Explaining away the ugly parts. I didn’t see that I was protecting Rowan at your expense.”

Tears filled her eyes.

“I’m so sorry,” she said. “I know ‘sorry’ doesn’t fix what happened. I know I helped her hurt you by refusing to see what was right in front of me.”

I leaned against the wall, the coolness pressing between my shoulder blades.

“I wish you’d believed me sooner,” I said.

“Me too,” she whispered.

“I wish you’d believed Elise,” I added.

She winced.

“Me too,” she repeated.

We stood in silence for a long moment.

“I’m starting therapy,” she said finally. “Real therapy. Not the kind where you complain about other people and leave. The kind where they tell you the truth even when you don’t like it.”

“I hope it helps,” I said.

I meant it.

I didn’t hug her.

I didn’t tell her it was okay.

I let the apology exist without rushing to soothe it away.

The Victorian house—Eleanor’s house—became both refuge and project.

It sat two neighborhoods away from downtown, a three-story blue-grey home with peeling paint, crooked shutters, and a front porch that sagged a little at the left corner.

Growing up, we’d only visited a few times. Eleanor had been the “odd” aunt, the one who never married, who read thick books and wore black turtlenecks even in summer.

“She loved you,” Elise told me once, eyes soft. “You reminded her of herself.”

The will had stunned everyone.

“To my niece Avery,” it had read, “I leave the house. Because she will know what to do with it when she’s ready.”

At the time, Mom had called it impractical. Rowan had called it unfair.

Now, as I scraped old wallpaper and sanded down banisters, I started to understand what Eleanor might have meant.

Restoring the house was like restoring myself.

Room by room, I peeled back layers of other people’s choices.

In the parlor, I tore down floral paper Mom had insisted on when Eleanor was too frail to argue. Underneath, I found the original plaster, cracked but solid.

In the smallest bedroom, tucked under the eaves, I found a box of Eleanor’s journals. Pages and pages of neat handwriting about books she’d loved, protests she’d attended, students she’d mentored quietly from her position as a librarian.

One entry, written when I was ten, stopped me.

“Took Avery to the museum today,” she’d written. “She asked a question about every painting. She sees more than they give her credit for. I worry about that. In families like hers, the one who sees is often the one who is asked to close her eyes.”

I sat on the bare floor and cried for a long time.

When the house was finally structurally sound and habitable, I made a decision that surprised even me.

I didn’t move in.

I turned it into a place I wished I’d had the first time I thought maybe “clumsy” wasn’t the whole story.

We called it The Eleanor Center.

At first, it was just a name on paper, a non-profit form filed with the state, a bare website.

Then, slowly, it became something real.

A resource hub for people trying to untangle family-made wounds.

We offered support groups for adult children of emotionally abusive parents. Workshops on identifying coercive control. Legal clinics run by volunteer attorneys who explained things like restraining orders and tenant rights in plain language. A lending library of books I wished someone had handed Mom thirty years ago.

We didn’t call it a “shelter.” That wasn’t our lane. But we knew the number of every shelter in the city.

We weren’t therapists, but we built a directory of those who understood that “family drama” can be a mask for something far more dangerous.

Some nights, I sat in the front room—once Eleanor’s study, now filled with mismatched chairs and secondhand rugs—and listened to people tell stories that sounded like mine in different costumes.

“My sister always ‘joked’ about how I shouldn’t have been born.”

“My mom says I’m ungrateful whenever I bring up the past.”

“My family calls me dramatic because I don’t want my kids around my brother.”

Every time, I said the words no one had said to me at twelve, at eighteen, at twenty-nine, at thirty-six.

“I believe you.”

Five years after Rowan’s arrest, the protective order still hung like an invisible fence between our lives.

She’d completed her mandated therapy. Probation had ended without incident. As far as I knew, she’d moved to another city.

We didn’t speak.

Occasionally, Mom would mention her in emails.

“Rowan started a new job,” she wrote once. “She seems… calmer. Her therapist says she’s making progress.”

Another time: “Rowan asked if you’ve forgiven her. I told her forgiveness is not a right. It’s a possibility.”

Reading that, I realized Mom really was changing.

We were not close. Not in the Hallmark-movie sense.

But the distance between us now felt chosen, not imposed.

We met for coffee once a month in a neutral cafe. We talked about books. About Gerald’s retirement. About Elise’s gardening obsession. Sometimes about the past, carefully, like handling a box of glass ornaments.

“I won’t ask you to pretend it wasn’t bad,” Mom said once, staring into her tea. “Or that I wasn’t part of the problem. I just… hope there’s still room for me in your life somewhere. Even if it looks different.”

“There is,” I said. “But it’ll never look like it did. That’s… a good thing.”

She nodded, accepting that.

One rainy Saturday, as I was locking up The Eleanor Center, a woman stepped in, damp hair curling around her face, eyes rimmed red.

“Sorry,” she said, voice shaking. “Are you… closed?”

I hesitated, then smiled.

“We were,” I said. “But come in. It’s okay.”

She stepped over the threshold slowly, like crossing some invisible line.

“I don’t know if I’m in the right place,” she said. “It’s just… my sister and I had this… incident. Everyone says I’m overreacting. That it was just a joke. But my ribs still hurt, and she’s laughing about it, and my mom says I bruise easily, and I just… I don’t know anymore.”

She stopped, choking on the words.

I gestured to a chair.

“You’re in exactly the right place,” I said.

As she sat and began to talk, I felt something settle inside me.

Not a happy ending, exactly.

But a right one.

Some people say family loyalty means sticking it out, no matter what. Enduring anything. Swallowing everything.

I’ve learned that real loyalty—real love—doesn’t demand silence in the face of harm. It doesn’t ask you to trade your safety for someone else’s comfort. It doesn’t call you dramatic when you’re bleeding.

Sometimes, loyalty to yourself means stepping away from the table where you’ve always been the punchline.

Sometimes, it means listening when a doctor looks at your X-ray and says, “Someone did this to you,” and letting that truth rearrange everything you thought you knew.

Sometimes, it means watching your sister get handcuffed in front of the family that never believed you—and choosing, afterward, not to build your whole life around that moment, but around what came next.

The bruise behind my ear has faded.

The hairline fracture has healed.

The old rib aches sometimes when the weather changes, a quiet reminder.

But the deepest healing isn’t in the bones.

It’s in the way I can now walk into a birthday party, blow out candles in my own kitchen, surrounded by people who don’t think “love” and “hurt” are synonyms—and know, in the marrow of me, that I’m not there to be the joke.

I’m there because I belong.

Because I chose them, and they chose me.

And because this time, if anyone ever tried to push my head toward a cake, there would be a dozen hands ready to catch me.

Including my own.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

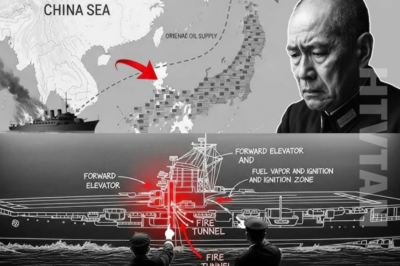

CH2. The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight

The Day Japan’s Oil Lifeline Died — And Its War Machine Collapsed Overnight The convoy moved like a wounded animal…

CH2. How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster

How One Girl’s “CRAZY” Chalk Trick Made German U-Boats Sink 3 TIMES Faster Liverpool, England. January 1942. The wind off…

CH2. She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors

She decoded ENIGMA – How a 19-Year-Old Girl’s Missing Letter Killed 2,303 Italian Sailors The Mediterranean that night looked harmless….

CH2. Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming

Why Patton Alone Saw the Battle of the Bulge Coming December 4th, 1944. Third Army Headquarters, Luxembourg. Rain whispered against…

CH2. They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass

They Mocked His P-51 “Suicide Dive” — Until He Shredded 12 Enemy Trucks in a Single Pass The Mustang dropped…

CH2. How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat

How 1 British Boarding Party Stole Germany’s Enigma Machine From a Sinking U Boat The North Atlantic in May was…

End of content

No more pages to load