My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And then..

Part One

I was already awake when her fist hit the door.

It was the way Lisa knocked when she wanted to be heard by the whole block—three hard bangs, a beat, then three more. I lay there watching the pale square of El Paso morning creep up my wall and listened to the house catch her mood: the rattle in the hallway vent, the kitchen chair she always dragged out too far, the cupboard she closed like it had wronged her.

“Karen,” she hollered through wood. “Up. I’m not running a charity.”

I could hear Liam too, his voice lower, blurred by the wall. “Deadbeats always sleep in.”

I swung my legs over the side of the bed and let my heels rest on the cool spot on the floor where Dad used to drop his work boots. If I kept breathing slow, I could almost pretend it was any other morning in the house Juan Alvarez had built with a stubbornness that showed itself in straight rooflines and a porch that didn’t sag under laughter. Mom, Donna, had been gone five years; Dad followed two later, leaving the rooms quieter and the house heavier in the way houses get when they’re carrying memories nobody dusts.

There are polite ways to ask for rent from a person. Screaming isn’t one of them. But screaming had always been Lisa’s idiom. She’d been good at it since we were kids—voice big enough to fill a grocery store aisle so everyone saw her choose the cereal, dramatic enough to make teachers stop picking on both of us when she failed to turn in homework because she’d forgotten to bring it home.

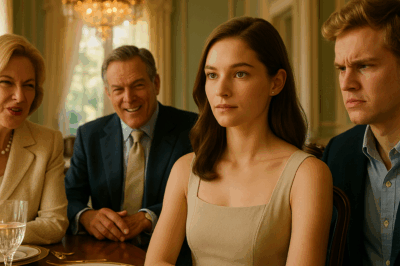

In the kitchen she stood with her hands on her hips, chin tipped high like she could will a crown onto her head. Liam lurked by the stove in an expensive t-shirt with a logo too discreet to be anything but loud.

“There’s your coffee,” Lisa said, pointing her chin at a mug on the counter like I should curtsy with gratitude. She’d poured it black, no sugar. I drank it that way anyway, not because she remembered, but because caffeine didn’t need help and I didn’t need sweetness from her.

“You’re up early,” she added in a voice that tried for casual and landed on sharp. “Big day.”

I looked at the steam curling from my mug instead of at her. “For you?”

“For all of us,” she said. “This house is too much for you to handle alone. We’re thinking it’s time to sell. Get you something smaller. Maybe a condo downtown. Less… responsibility.”

Liam finally looked up from his phone, thumbs still moving. “Market’s hot,” he said, like he was saying happy birthday. “We’ve got buyers ready.”

I held my mug and counted to ten the way Mom taught me when I was ten and Lisa had jammed my favorite pencil into the pencil sharpener and twisted until the eraser screamed. I didn’t look at the porch or the wall with the tiny nick from the day Dad, laughing, tossed me the tape measure and missed. I didn’t look at the dent at the base of the hallway where Lisa slammed her suitcase into the corner the night she moved back in after her first attempt at moving out didn’t stick.

“What happens if I don’t agree?” I asked.

They shared one of those glances people share when they’re sure they’re in the same sentence. “We’ll handle it,” Liam said. “Paperwork. Buyers like this house.”

Buyers. Like the place where Dad taught me to check oil in the driveway. Like the kitchen where Mom taught me to pinch empanadas closed with fingers that learned it faster than I did. Like the bedroom I had painted pale yellow in a weekend because I needed the light.

I took a slow sip and smiled like I was slow too. “I’ll think about it.”

They left for work—Lisa for her job staging other people’s houses, arranging furniture into poses that suggested lives nobody lived; Liam for… whatever Liam called what he did. Insurance? Investments? Some job with a title that sounded like money.

When they were gone, the house exhaled. I rinsed my mug and went to the garage where Dad’s bench sat under a pegboard that still held tools he had labeled in Sharpie in a handwriting that never learned to be careful. Behind a panel he’d taught me to move with a pull and lift—I was six the first time, and it felt like magic—was the safe Lisa didn’t know existed. Some people lock up cash. Dad locked up faith. The envelope with Sophia’s letter was right where I left it. Dad’s will, the deed, the bank statements. Karen, you’re the one who keeps things steady, he’d said in a voice sandpapery with chemo months. This house is yours to hold.

I ran my hand over paper the way you do to make sure it doesn’t disappear like the people who signed it. Lisa had always been the hungry one. Dad had always been the one who saw the hunger and fed what he could. That’s love when you’re a parent. It’s less noble when you’re a sister. He left Lisa things too—pieces of Mom’s jewelry with notes saying, for the dress you loved, for the day you need to remember where you come from. He left the house to me. He’d known it would need someone who understood what a promise looks like when it’s wrapped in walls.

Through the garage window I watched Lisa in the yard, pacing with her phone to her ear, nodding the way she does when she’s already decided to agree but wants the person on the other end to feel like they earned it. It could have been a client. It could have been the woman who sells Layne Street bungalows to men who grew up in neighborhoods without mesquite and think land smells like water. I locked the safe. I wasn’t moving yet. But moving was coming.

Dinner that night was quiet enough to hear the knife hit the cutting board. Lisa scrolled while she ate. Liam pushed rice around his plate like it owed him something. I talked to the house in my head—porch swing’s got a sliver loose, faucet needs the good plumbing tape, front door sticks when the heat gets ahead of itself. When I mentioned the swing, Lisa waved a hand without looking up. “We’ll see, Karen. You’ve got enough on your plate.” I nodded. I did.

The next morning came with another knock and a sweeter voice, which is how you know a person thinks you’re not just wrong but also useful. “Karen,” she sang through the door. “Errands today. We’re busy.”

“No,” I said to the ceiling. Then I went to the kitchen and listened without answering.

“We’ve got a showing today,” Liam said as if we were a we and showing was a blessing.

“Do they know it’s not for sale?” I asked.

He grinned. “Not yet.”

I fixed the porch swing that afternoon because objects keep their promises if you keep yours to them. It helps to do something, sometimes. The rhythm of the hammer made my arms heavier and my head lighter. Sun burned the part in my hair. In the slant of late afternoon I checked the safe again. Mom’s pearls were still in the pouch at the back. Lisa had asked to borrow them for a gala, once, and I told her they had a clasp that needed fixing because I knew she’d pawn them when rent came due on a party. She didn’t know about the second compartment, and I didn’t remind her.

At dinner she complimented the swing. “Nice,” she said, as if she’d thought it up. On the way to bed she said, “By the way, what’s Sophia’s number?” and I said, “Which Sophia?” and she said, “Never mind,” because she’d forgotten Dad’s lawyer’s last name but wanted to remind me she was thinking about lawyers.

The week went like that. Lisa got nice. Liam got practical. I got patient.

I baited the hook at breakfast on Saturday. “Carla at the hardware store,” I said, stirring my coffee, “is thinking of selling her place up near Las Cruces.” I’d said it Los Cusus, on purpose. Lisa’s ears perked. “Las Cruces,” she corrected, and for a second the girl who won the spelling bee in fourth grade glowed through. “It’s a gold mine for short-term rentals. Hiking. Balloons. Karen, you’d love it up there. Imagine. Mountains. Sunsets. Less… yard.”

“Sounds like a fit,” Liam said, buttering another slice of toast like he was trying to fill himself with carbs and chutzpah. “We’ll find you a place. You settle in. We handle the heavy lift.”

I walked the neighborhood that afternoon, slow, like I was measuring it. Carmela waved from her porch. “Your roses need water,” she called. “The whole city needs water,” I said back. I stood at the corner and watched the house from across the street and tried to see it the way a person who didn’t grow up under its roof would see it. Big lot. Good street. Good bones. Enough elbow room to raise a kid with bark under their nails. Enough sky to remember your place.

On Sunday I found a note under my door in Lisa’s handwriting. The house is for both of us. I burned it in the grill because dramatic gestures satisfy something in the body and the smell of smoke can cover a lot of sins.

On Thursday a man with a clipboard knocked. “Here for the appraisal,” he said. He had a tie too wide for the decade and a smile too ready for this address. “For what?” I asked. He blinked like I was the one being rude. “The sale.” I closed the door gently without giving him a name to write down. Then I called Lisa.

“Oh,” she said. “Mix-up. I’ll handle it.”

On the security feed I installed the next week—one camera tucked into the porch light, one watching the garage through a knot hole—Lisa tried her keys in the garage door while Liam stood under his truck’s raised hood pretending to fine-tune something. Mrs. Torres walked by, stopped, planted her feet. When Liam said whatever he said, she pointed at the porch camera like she could see it and at the Beware of Dog sign that we kept mostly for nostalgia since Dad’s Labrador has been gone ten years, and tugged her Chihuahua down the sidewalk with a little snort. They went inside, Hampton Bays bravado wilted.

I didn’t call them on it. I called Sophia.

“I want a meeting,” I said when she picked up. I could hear legal pads in her voice. “Bring everything.”

Sophia had known Dad since he was twenty and a dream and a bank teller. She set three files in front of me in her office, each fat with the kind of authority people like Lisa confuse with magic. “Juan’s will names you sole owner,” she said. “The deed transferred clean when he passed. Taxes are current. Title’s yours. There is no scenario in which this house moves without your signature. You understand.”

“I do,” I said. “But we’re going to move it.”

She smiled. “Good. It’s easier when the person who knows what’s right also knows what she wants.”

I moved papers into a safe deposit box—Dad’s letter, Mom’s pearls, a copy of the will with a sticky note in Sophia’s hand with her office number and the words, Call me if anyone tries anything cute. I moved cash from the back-up account Dad had taught me to use as a safety net—for tires and tuition and trouble, he’d said—into another bank across town, one with a lobby that still smelled like citrus because the teller liked to wipe fingerprints off glass the second someone left them.

At home, I built the thing that would make their plan matter less: a skeleton of a trust that would take effect when the house sold, naming not me but the idea that felt most like justice—scholarships under Dad’s name for kids who wanted to learn with their hands at the community college he’d taught me to treat like a good toolbox. “Juan’s Fund,” I wrote in the margin and felt something in my chest ease.

At dinner that night Lisa slid a folder across the table. “Just paperwork,” she said. “To make things easier.”

Liam leaned forward, elbows on wood like he was in a barfight. “You stay here as long as you want,” he said. “We take on maintenance. We handle taxes. You sign. We’re all happy.”

I opened to the first page. Legal language laid back and smiled at me like a dog that bites. On page two the word QUITCLAIM shouted in twelve point font.

“No,” I said, and it was easier than I thought. “I’m not signing anything you drew up while I was in the shower.”

Lisa’s mouth kicked. “You’re being ridiculous, Karen. This is family.”

“Family shows up to funerals,” I said, and for a second she looked like I had slapped her. Then she shrugged it off like water.

Liam tried sober menace. “We’ve talked to a lawyer,” he said. He was lying; I could see the place where the truth would have sat on his face if he had meant it. “Guardianship is an option if you can’t handle the house. It’s a lot—”

I laughed, not loud and not kind. “Call me incompetent,” I said. “Take my house. Call it help. Record yourself saying it so the judge can hear you.”

The fighting that followed couldn’t be called a conversation, so I won’t recount it. The threats were old; the leverage was not. They left me with our silence and their folder. I put the folder in the drawer under the silverware because I come from people who hide important things in obvious places and tell themselves nobody is that smart or that stupid. Then I copied the letter Dad wrote me before the hospital took his handwriting and put one copy in my jacket pocket and one in the safe deposit box and one in the back of the photo of us on the porch the day we hung the swing.

Lisa’s next big move came wrapped in tickets. “San Diego,” she announced one evening, dropping an itinerary on the table. “First week of April. Beaches. Tacos. Recharge.”

“You should go,” Liam said, slick as new oil. “You need a break.”

“I thought you had a showing that week,” I said, and watched Lisa blink.

She smiled fast. “We rescheduled.”

“You booked Mrs. Torres to check on the house while we’re gone.” I watched her blink again. “That’s considerate.”

The click when their plan landed in my head was satisfying in a way that should make any adult suspicious of their own brain. I let it settle there, under my tongue, while I called Sophia about the last thing we needed to do to make sure the house did what Dad wanted it to when it flew this nest: sell it before Lisa and Liam could find a man who would tell them theft looked good in a sport coat.

The trip looked like a trip. Coronado made at least three attempts daily to make me forget I was mad, and I let it succeed for the length of a fish taco. Lisa tried for sister; I gave her cousin. Liam tried for chill; I let him. On day two I checked the camera feed during one of Lisa’s blessedly long showers. The front porch empty. The garage closed. On day three the feed showed Liam’s truck in the driveway, Lisa’s sedan behind it. She tried the front door first—one, two, three in a false rhythm—and when that failed, Liam crouched by the garage like a man practicing how to explain a bruise to a woman with a flashlight.

Mrs. Torres, my Mrs. Torres, walked by with her tiny dog and stood at the end of my driveway like an oak. On the feed I watched her point to the porch light with the camera in it and then point to her own eyes. I watched Lisa spread her hands and reshape her mouth around a plea. I watched Mrs. Torres shake her head and go on her way, dog feet making little waggles of indignation.

On our last morning in California, Lisa was quiet in the hotel breakfast room. She cut a piece of cantaloupe into perfect squares and didn’t eat them. Liam scrolled and scrolled like his phone could act as a time machine. I ate pancakes and thought about signatures.

Back in El Paso, the first thing I did was stand in the living room and breathe. The second was call the agent Sophia recommended—the one who understood that some houses require particular hands. He met me there two days later in a collared shirt that said he knew how to say ma’am without condescension and told me what I already knew. “Good bones,” he said. “Good lot.” I nodded. He took photos that made the rooms look like themselves. We signed a listing I had asked Sophia to read three times before I let my pen touch it. The price was fair. The offers came fast.

Lisa and Liam didn’t know until the “For Sale” sign went up in the yard the day the listing went live and the couple in a sensible Subaru came to see if the back bedroom caught morning light. Lisa saw them from the kitchen while she pretended to wipe the clean counter. “What is that?” she asked, as if pointing at a stain. The agent smiled. “Showing,” he said. “House is on the market.”

“Whose market?” Liam said from the doorway.

“Karen’s,” Sophia said when she walked in with a stack of papers thicker than a Bible and thinner than a novel. “She’s the only seller here.”

It took them a beat to realize what that meant. It took exactly one more for their voices to sharpen. “You can’t,” Lisa told Sophia, then told me. “We live here.”

“You occupied it,” I said. “You don’t own it.”

“You’re keeping the money?” Liam asked, the ask burning off before the second word.

“I’m keeping a promise,” I said. “And building a fund in Dad’s name for kids who want to learn how to fix things with their hands and their heads.” I didn’t owe them the information but it felt good to say it aloud.

They moved out the day before closing. No long speeches. No apology. No plates left dirty in the sink for me to wash. El Paso light flooded rooms I hadn’t seen empty in years, and we all looked different in it.

Once the last signature dried, I stood on the porch with the keys warm in my palm. Then I handed them to a woman who had stood on the grass with her wife and told me they loved the tree out front because their twelve-year-old likes to climb, and the old swing made her imagine flying. I said, “Watch for splinters,” and she said, “We’ve got Band-Aids,” and that is how some promises are kept.

I didn’t cry until I loaded the last box into my car and looked up to see Mrs. Torres on her porch with her dog and a thumbs up. Carmela waved from her yard. “Good girl,” she called. “Good girl.”

A week later, in Lisa’s old closet in the room that looked wrong without her loudness, I found a small box with Mom’s pearl earrings tucked into tissue and a note written in Lisa’s slanted hand. Karen, I know you hate me. I couldn’t sell these. They’re Mom’s. And yours. I’m sorry. It wasn’t redemption. But it was a crack in a wall that had seemed to grow itself out of concrete.

I moved into a smaller place a few blocks away because I wanted my feet to remember this neighborhood. I tipped soil from Mom’s garden into pots and coaxed her rosemary to take to its new home on my balcony. I put Dad’s ledger on my shelf and the letter he wrote me in a frame above the small table where I drink coffee and don’t have to listen to people who don’t love me tell me to be grateful.

Sometimes the house catches me in the grocery store—tile salt and the rows of sopa noodles that have nothing to do with weather—and I have to stand still in an aisle until the part of me that wants to go back remembers why we don’t. Sometimes I drive past and the new owners are in the yard with a twelve-year-old hanging upside down from the tree, and I feel the kind of relief that tastes like sugar after you’ve been careful for a long time.

“What do I do with the note?” I asked Sophia once, as if she had a legal code for forgiveness. She said, “Put it somewhere you can see. Let it make you gentle without making you stupid.”

So I keep it taped inside the kitchen cabinet where I used to keep the sugar. Some mornings I open it for salt, read it once, and then put salt in the water anyway because even change needs to be seasoned.

Part Two

After the sale, quiet moved into my life like a new roommate. I wasn’t used to it. I kept looking for her shoes at the door and her voice on the stairs. Some nights I forgot and set an extra fork on my little table. But quiet was polite. She washed her own dishes. She didn’t leave lights on. She made it possible to hear things I had pretended not to hear while Lisa scaled every conversation like a climber who thought every mountain was worth it because she wanted to see the view.

The last pieces of the plan clicked into place the way well-cut joints do. The title company’s check cleared. The scholarship fund Sophia created in Dad’s name got fat enough to sign its own papers. I sat at a meeting with the director of the trades program at the community college on Yarbrough and listened to him explain how many kids aged out of wanting things because they never got to hold something well-made enough to know that they could learn to make it themselves. “We can buy tools,” he said. “We can bring in a welder for a week to teach. We can pay stipends so kids don’t have to choose between class and helping at home.” I signed the papers and felt the house settle into this new shape, right-sized.

Three weeks later, the foreclosure notice went up on Deborah and Liam’s condo because the guarantee on the mortgage had been my name and I had peeled it off like tape from a window I needed to see through. Lisa left three voicemails the day the bank called her. Her voice cracked on the place where she asked me to fix it. “I know you’re mad,” she said in one. “We can work this out.” I deleted them without listening to all the way through because my therapist had me practicing the art of stopping when the sentence is already a lie.

The community did what communities do when you break the rule at the center of their story with arrogance: it let you learn alone. Lisa’s favorite yoga class told her they were reassessing membership requirements; she told Susan they’d be open again in “a few months” after “some rebranding.” Liam’s Thursday golf foursome found themselves suddenly busy. Their regular dinner reservation at a place that plate-drizzled everything with balsamic got lost in a system that is never wrong.

I didn’t take satisfaction in that. The feeling I felt was something softer, like a bruise that stops hurting because the work of healing is done and now you can finally touch it.

On a Monday morning in July a short kid with scabbed knees and the stubborn jaw of a person who had been told to work instead of talk came into the foundation office with a mother who had smiled so hard at the bank teller her face was still sore. “My name is Juan,” he said, and I felt the room do a small, private thing in my chest that had nothing to do with grief and everything to do with coincidence. We gave him a stipend and a book and the keys to a locked cabinet full of good saws.

“Your dad would like this,” Sophia said afterwards.

“He liked the sound a tape measure makes when it zings,” I said. “He’d have liked the way that kid said yes like he meant it.”

The first day Mrs. Torres saw the new family throw a birthday party in the backyard for a child whose friends still wore masks under their chins because their parents weren’t ready, she texted me. Cake survived. No one’s face in it. I laughed in a way that felt like my rib cage had been waiting for the joke.

At the grocery store I ran into Liam by the frozen corn. His hair had lost the product and discovered how to behave. He held a basket with eggs, bread, and ramen like he was practicing a way to carry less. “Karen,” he said.

“Liam.”

He stood there, and I could see the scene play out across the front of his face as he decided whether to ask or apologize. He chose something in the middle. “We could have done that better,” he said.

“We could all have,” I said, which was true and not an invitation.

“Lisa…” He started, then stopped, then started again. “She kept Mom’s pearls,” he said, like a man who didn’t remember which woman those pearls belonged to. “She didn’t pawn them. She says you think she did. She kept them.”

“I know,” I said. “I found them.”

“She left you a note.”

“I know,” I said again. “I read it.”

He nodded and shifted his weight like he was fidgeting with something in his head that didn’t fit anymore. “We’re… trying,” he said.

“Good,” I said, and moved down the aisle, because I had milk thawing in my basket and a life that didn’t need his apology to hold.

Lisa didn’t call again. But one afternoon in September when the heat was a memory and the rain had surprised the street into smelling like something alive, I found a postcard in my mailbox from Las Cruces. You were right, she had written in her stilted slant. It’s beautiful. I’m working. I’m sorry. She had drawn a cartoon of the Organ Mountains on the back like I wouldn’t know what they looked like. I taped it next to Dad’s letter in my cabinet of sugar and salt.

On the anniversary of Dad’s death, I took the day off and drove to the place he taught me to skip rocks. The water has gotten shallower; time takes back what people borrow. I stood on the bank and thought about how much our best people teach us to love our lives by being entirely themselves in front of us. I threw a rock half as far as I wanted to. It made three skips, which I decided was a sign of nothing other than physics.

When I got home, Sophia called. “The first round of scholarship checks cashed,” she said. “They sent thank you notes you don’t have to read but probably will.” I sat on my rug and read them all at my coffee table like a teenager. The ink pooled in some letters and skipped in others; there were misspellings I didn’t correct with a red pen in my head. Thank you for seeing me. I want to be like your father. This makes it possible. The absolute courage of kids telling strangers their hopes would embarrass me if it didn’t delight me.

On a Saturday night that fall I cooked empanadas with a recipe that took me three tries to not ruin. I pinched the dough closed with my fingers the way Mom had taught me, shamefully relieved that no one was there to tell me I was doing it wrong. Half went to the neighbors because traditions only live if they leave your kitchen. Mr. Morales said they were good, which from him meant they were almost as good as his wife’s once had been; he smiled like he’d allowed a compliment and gone back on his word.

One day I took a drive by the house and did not cry. The swing still hung in the right place; the wrench still on the pegboard in my mind. The new owners had painted the door a color I would never have chosen but liked anyway. The little girl who climbed the tree sat high with a book and a grin like she had learned the secret of height. Her mother waved at me because this is El Paso and we wave; I waved back and kept driving.

There is no satisfying cinematic moment where I told Lisa I forgave her and we hugged and promised to be good forever. Forgiveness in real life is less grand: finding a note in a closet and putting it where you can see it when you start building the sort of rage altar that requires daily devotion; buying an extra painting kit for the scholarship kid who wants to learn to pinstripe the side of his uncle’s truck; sending Mrs. Torres a poinsettia big enough to overwhelm her porch because she stood in your driveway and stared down a locksmith.

If a story needs a moral, maybe it is this: the law of houses is the law of promises. Don’t make one inside a set of walls you don’t intend to keep. And if you inherit a promise from someone you loved, keep it in a way that makes strangers feel what you felt: safe enough to become themselves inside it.

Dad didn’t give me the house so I could fight my sister. He gave me the house so I would learn that my job is not to keep chaos out of rooms but to make the rooms strong enough to contain it. Sometimes that means selling. Sometimes that means locking a door. Sometimes it means saying “no” at six in the morning while your sister pounds with all the entitlement she was taught to believe was concern.

The last thing Dad said to me in the hospital that sounded like him and not like medicine was, “Make this place yours.” I thought he meant the house. He meant my life.

So I did.

END!

News

A Political Firebrand SILENCED In Utah — Charlie Kirk’s American Comeback Tour Ends In TRAGEDY

Under a campus tent at Utah Valley University, a single shot cut through the noon crowd, striking the 31-year-old Turning…

My In-Laws Invaded My Dream Home — So I Arranged A Special Delivery That Made Them Permanent… CH2

My In-Laws Invaded My Dream Home — So I Arranged A Special Delivery That Made Them Permanent… Part One…

At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was. CH2

At the Mall, I Caught My Husband with a Stranger Trying on a Wedding Dress—And the Truth Was… Part…

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… CH2

My Fiancé’s Family Humiliated Me With Their Secret Prenup — What I Revealed At The Altar… Part One The pen…

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… CH2

My Parents Assaulted Me As My Daughter Watched — I Let Them Stay Before Destroying Their Lives… Part One The…

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… CH2

My Date’s Rich Parents Humiliated Us For Being ‘Poor Commoners’ — They Begged For Mercy When… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load