My sister pushed me out of the helicopter and whispered, “You’ve always been in the way.” My husband just stood there. He knew. They planned it.

Part One

Everything—the company, the five–million–dollar payout, the freedom to rewrite my life without me in it—sat on the line between my sister’s palm and the open winter air.

She leaned in so close her perfume drowned the pine and metal. Her hair brushed my cheek, and under the chop of the rotors she whispered, “You’ve always been in the way.”

Then she shoved.

There wasn’t time to scream properly. There wasn’t time for anything except the shock of cold and the roar swallowing my name. The blades turned the sky into a disc. Snow rose up to meet me as if the mountain were a mouth opening wider and wider. For one bright, clean second the entire story of my life snapped into the focus you only get when someone else believes it’s over: the shop sign we lit ourselves the night my brand finally opened; Rowan’s hands guiding mine on the steering wheel in the dead of winter, telling me to trust him; my little sister at seven clutching my pinky in the dark during a thunderstorm, begging, “Don’t leave me, Selene. Promise.”

Trust, it turns out, is sticky. Betrayal is ice.

I didn’t want to die. The body knows the difference before the mind does. Instinct reached long before hope. Branches rushed up; I threw my arm; pain cracked through shoulder and elbow like lightning; bark ripped skin. I swung, slipped, caught again. The world didn’t stop so much as suddenly start obeying physics again. The branch sagged with my weight. I hung for a beat in a silence so loud my breath sounded like a siren inside my skull.

The helicopter dwindled into a dark punctuation mark. Fallon—my sister—would already be turning back to the cameras she had invited to catalog her carefully curated life. Rowan—my husband—would already be composing the face he wore for investors: ache at the edges, steel in the middle, calculation behind the eyes. If they looked down at all, they would see the wind rewriting the shape of the snow where I should have vanished.

Five million dollars. That was the number in the policy drawer Rowan had insisted we update “for prudence” after the company’s year-end review. I’d laughed and said we couldn’t afford to die. He’d said that wasn’t how it worked. He’d said, “You and me, Selene. We do things right. We leave no loose ends.”

When the numbness started creeping from my fingers into my forearms, I hauled my body closer to the trunk, locking my knees against bark and holding fast while my shoulder screamed. I said the three words my mother used to say under her breath when the rent was due and my father left: “You don’t quit.”

I didn’t. Not on a mountain because a woman wearing my last name like a costume decided my expiration date.

The ranger cabin wasn’t a miracle—miracles come in glory—it was a structure. Four walls. Stove. Blankets that smelled like people who’d been colder than me and survived anyway. I stumbled through the door blinking blood and snow. I wrapped a sling around the arm that throbbed and bent a stick into a crutch. I bandaged my leg with gauze crumbling with age and steadied my face in a tarnished saucepan lid to clean the cut on my temple. There’s a small and genuine power in seeing your own eyes look back and refuse to cloud.

By the stove sat a radio half-buried in dust. When I twisted the knob, static cracked like frost. Then a voice cut through like a knife through paper. “…woman presumed deceased, body unrecovered… authorities say she fell from a helicopter in a tragic accident near Ridge Seven…”

The cabin’s air went thinner. Words followed my name like fire running behind a fuse.

I used to think death would be something you’d feel from the inside: the slowing of your heart, the thinning of your blood, the softening of edges. It turns out death—other people’s version—happens outside first: in the tone of a stranger reading your life into a microphone, in the way the word “presumed” wraps itself around you like a net, in the sound of your sister practicing grief into a camera lens.

The rotary phone on the wall looked like a relic until I picked it up, and a dial tone surprised me so much I laughed. Then I remembered a number kept where my ordinary life used to be: Vera’s. We served two deployments side by side—her with a laptop that could find rats disguised as accounts on the other side of the planet; me with a map always in my head and a stubbornness that made superiors sigh and then sign off anyway.

She answered on the second ring. “Yeah?”

“It’s me,” I said. “I am not dead.”

Silence, then an inhale so sharp I felt it in the wire. “Where are you?”

“Cold,” I said. “Alive. Aspen ridge somewhere. And, Vera—”

“—I know,” she said. “They’re already talking. I’m coming.”

I hung up and pulled a heavy ranger coat from the peg. On the door someone had carved a single word with a knife tip: STAY. I took the opposite counsel. Stay is what Fallon wanted for me forever—in her shadow, in her story, under her thumb. Go is what saved my life.

Outside, the sky had turned the pearl gray of mornings that plan to be bright no matter what happened to you. I cinched the coat and stepped back into a world that had decided, briefly, to erase me. I had different ideas.

The diner at the base of the mountain had a neon sign that flickered OPE. The H clung by one end and refused to die. Inside, heat hit me like a mercy I didn’t know I still deserved. The waitress looked at my face and moved toward the coffee pot without asking. I nodded at the payphone in the corner. She nodded back like she saw women crawl in from the cold and start again all the time.

On the mounted TV, my husband stood at a podium next to an easel with my headshot and a black ribbon. He had the microphone grip I’d watched him practice in our bedroom mirror. “Please respect our privacy,” he said to the room that definitely wouldn’t, his voice breaking on privacy like the counselor who got into your head on purpose. “Our family is asking for space.”

Fallon pressed her face to Rowan’s shoulder and he adjusted his arm around her like he had learned in a class. Someone had told them grief works better in thirds. I recognized the dress she wore from the last gala I had sent a check to and not attended because I was writing copy for a launch. The camera cut to my company’s logo behind them. Mine. Built with a thousand naps deferred and a favorite novel on the shelf still unread.

The first voice to my left that wasn’t mine asked, “You okay, miss?” The waitress had slid the coffee and stacked two extra creamers next to it like armor. I nodded, which was a lie, and walked to the phone.

“Vera,” I said when she picked up. “It’s time.”

“Where?” she asked.

I turned my head and read the address off the menu board that still listed a meatloaf special from 1987. “Fifteen minutes,” she said.

Fifteen minutes is a lifetime if you’ve been pushed from the sky by the only person who knows the names of the ghosts in your childhood bedroom. I filled it with decisions. Not the big ones (press charges, press conferences, press on) but the small ones that get you to the bigger: stand up straight, swallow coffee that tastes like the color brown, don’t pass out when your leg reminds you it exists, put your hair in a bun even if it has dried blood in it, wash your hands like it’s a ritual.

Vera arrived wearing a coat that had more pockets than most men’s arguments. She slid into the booth, skimmed my face, didn’t say sorry—the best kindness—and opened her laptop. “They filed the claim,” she said without preamble, tapping a screen with a list of transactions. “Five mil. ‘Continuity of business in event of disappearance or death.’ How considerate.”

“Rowan’s signature?” I asked.

“And yours,” she said, zooming into the scrawl that looked like my hand had been taught by a copier. “They used a digital template. Amateur hour. Good.” She looked up. “You want quiet or loud?”

“Loud,” I said. “Louder than rotors.”

“Then we start with your funeral.”

I don’t recommend walking into your own memorial service in uniform if you can avoid it. It’s dramatic, ill-mannered, and the kind of thing people will talk about at barbecues for a decade. It is also—under certain very specific circumstances—the most accurate message you can send.

They had chosen the big room at McDonough Memorial because it has pillars and a long aisle that makes grief look like a procession. The air smelled like lilies and lemon cleaner and the particular perfume of women who know their place in a picture. I stood in the vestibule long enough to hear my name as a past tense from a pastor who didn’t know me. Then I walked. My boots struck tile, not soft carpet. Heads turned like metronomes.

Rowan stopped mid-sentence. Fallon froze mid-sway, her handkerchief halfway to a face that could cry on command. The front row—board members, a senator who liked me when a camera was between us, my mother’s yoga friend who thinks gossip is a form of prayer—made a sound not unlike a flock of birds changing minds mid-air.

“Miss me?” I asked, because there are lines in life that come with their own soundtrack.

The whispers hit like sleet. The rumor mill does not start slowly; it detonates.

“Selene,” Rowan said, walking down the step like a man goes to a lectern, not his wife. “Thank God.”

I stepped back. “Don’t.”

Fallon pulled herself together and did the flanking move, the one where she arrives in your space as if she belongs there because she believes she does. “We’ve been so worried,” she said, mascara tracks like roadmaps down her face. Her eyes searched mine for a script she wrote. I didn’t give it to her.

“Save it,” I said. “For the cameras.”

Reporters have a special sixth sense for the moment a story stops reading itself and starts bleeding. They moved as one organism, microphones extending, bodies leaning. “How are you alive?” one asked, breathless. “Where have you been?” another. “Is it true you were unstable?” a third—the tabloids always show up on time.

I heard everything and nothing. On some level, I noticed the senator checking her phone. On another, I watched my mother’s mouth shape the word Selene like she was practicing saying it in the mirror later. Mostly, I saw Vera’s hand on the back pew signaling once: go.

“Good afternoon,” I said into no one’s microphone and all of them. “I appreciate your concern. I’ll be making a statement once my lawyer files what he’s filing. In the meantime, if you want a quote, this is the one you’re getting: you don’t get to kill me for profit.”

The funeral director, to his credit, swallowed his theology and didn’t argue. Vera touched my elbow as I turned and the crowd split for us—not the Red Sea as much as a whole lot of people suddenly unsure how close you’re allowed to stand to a person who shouldn’t exist.

On the way out, I stopped by the easel. In Loving Memory, the script read; my portrait stared back with a softness not actual to my face. I touched the black ribbon. “Wrong color,” I said. “White suits you better.”

Fallon’s fingers twitched on her handkerchief. She folded it back into a perfect square with a practiced thumb.

Back in Vera’s apartment, the laptop’s glow made the tiny kitchen look like a stage. We plugged in the drive a source had given us—someone who’d loved my sister in that way people love hurricanes: the electricity gets you, then the wind wrecks your life, and you pretend it was weather.

It turns out betrayal leaves paper.

Rowan’s emails read like a project plan done by someone who thinks hiding malice under bullet points makes it strategy. Risk: Selene blocking funds. Mitigation: medical incapacity filing. Threads between him and Fallon coughed up phrases like “narrative advantage,” “her episodes,” “family friend Dr. S. can sign off,” and the kind of euphemisms for murder rich people think make it something else.

My signature—fake—waved across transfer after transfer: continuity, continuity, continuity. Rowan had annotated one file with a smiley face. When I saw it, I laughed the kind of sound that makes people check your pupils. Vera let me. Then she slid me a mug and said, “Drink.”

They’d even drafted a press release for the company in case of tragedy. I recognized my junior PR manager’s style bent under someone else’s weight. We honor Selene’s vision by continuing the work she loved. I couldn’t decide whether to throw up or sue first.

“Freeze?” Vera asked.

“Freeze,” I said, and she called the lawyer she keeps for emergencies that require ties.

The next morning, we sat in a law office where the windows looked like money. The attorney clicked, frowned, clicked again. “They moved fast,” he said. “Filed for a temporary conservatorship, claimed mental instability. If you hadn’t walked into your own funeral, this would’ve been tied up by Friday.”

“Good thing I had other plans,” I said.

While the attorney filed, my phone buzzed with texts from an unknown number. Meet me. I know what they did. It wasn’t stupid to go see the sender; it was desperate, which is a cousin sometimes. I told Vera, and we went together because no one goes alone into a story that already tried to kill you.

The storage unit smelled like oil and secrets. The fluorescent lights flickered a Morse code I decided to read as keep going. The man who had texted me—Aaron—looked like a cautionary tale in human form: jaw clenched too much, hair walked through with both hands too often, limp healed wrong. He slid a key across the hall like it weighed him down.

“I kept everything,” he said. “Didn’t know why. Guess I do now.”

Inside, rows of boxes labeled in my sister’s careful hand. The labels read like history written by a winner who hadn’t met the last chapter yet: Selene—health, Continuity, Insurance, PR. Now and then her handwriting pinched small on a box like a person trying to say less than they’d done. I wanted to rip open the top box and throw up. Instead I opened the top box and cataloged.

Fake psychiatry notes on letterhead from a doctor who signs things when money and a weekend in Vail are involved. A draft blog post “from the founder” (Fallon) “about the loss of her sister and the way pain fuels leadership.” A series of texts between Rowan and Fallon about “ramp timing” and “out of the picture by end of Q1”—no names, only implication, like cowards do.

Then the video.

Vera pressed play as if the screen were a door she was opening for fresh air. Fallon, wine in hand, laughing into a camera someone else thought they turned off. Rowan, sleeves rolled up, leaning in with that grin people mistake for charm. “She’s always been in the way,” Fallon says to the lens. “You never liked her,” Rowan replies. She clinks her glass to his. “Easy money,” she says. “She never sees anything coming.”

They forgot the world isn’t only cameras you invite.

We didn’t stage a press conference; we staged evidence.

Outside the courthouse, the wall that faces the sun most of the day became a screen. Vera’s portable projector threw laughter in white and shadow twenty feet high. People stopped. Reporters stopped. Security didn’t shut it down because by the time anyone found an outlet to pull, a hundred phones had captured it and a thousand thumbs had pressed share.

Fallon shoved through the crowd with the fury of someone who believes public places belong to her by default. “Take that down,” she hissed at me, her face tight enough to hurt. “You don’t understand what you’re doing.”

“You’re right,” I said. “I thought you understood gravity.”

“It was an accident,” she tried, then, “We were trying to help you,” then, “You wouldn’t listen,” then, “This will destroy the company,” then, “You’re mentally ill,” and when that didn’t land in the faces watching, she defaulted to, “I will ruin you.”

“I’ve met ruin,” I said. “You aren’t it.”

Security pulled her back as she reached for me. A reporter yelled a question about charges. A board member pretended they had only met my sister at charity lunches and certainly never at a notarization of a line of credit. The senator found something fascinating about the concrete near her shoe.

Vera’s hand found mine. She squeezed once. Breathe. I did.

I left the projector running. The light washed over people’s faces while they watched wealth laugh about killing a woman for money and sympathy. The thing about truth—even the ugly kind—is that it changes the air. You can feel it settle like snow.

Rowan’s proposed settlement arrived two days later: a number with too many zeros to make a human noise, nondisclosure, admission of nothing, an NDA thick as a phone book. I put it under a coffee mug so it could be useful.

We filed the civil case. Miles—the attorney Vera called who always wears his tie like a joke he tells himself—stood in court with a file that weighed less than the fear in the room and won the injunction to put my accounts back in my name. The judge wore a pin on her robe that told me she’d been saluted before. She did not smile. She did not grandstand. She said, “You tried to erase her,” and then, “No,” in a tone that wasn’t for me or them as much as for the record.

Clara took the stand and said “I was ordered to change dates” out loud into a mic. Aaron handed over a copy of his ID with Regret written on it in a hand that looked a lot like a person who wanted to be useful after a season of being something else. Sometime in the third hour, my mother walked in and sat in the back pew as if someone had dropped her off at the wrong church.

Rowan wore a suit expensive enough to fool nobody. He looked smaller than the podium. Fallon’s new attorney—the last one disappeared between one hearing and the next—argued about context and accidents and the fog of love. The judge cut him off mid–metaphor. “I do not allow poetry in here,” she said. “Let’s stick to what happened.”

And what happened was this: my sister pushed me out of a helicopter. My husband watched. They timed it with a payout, pre-wrote the story, and practiced crying. They planned to bury me under paperwork if not snow. They failed.

I did not get everything back. I say that as a caution to anyone who wants tidy. Some friends decided my wrath made their stomachs hurt and told themselves both sides were bad so they could keep going to dinner with whichever person could still pay the tab. Some team members at the company found jobs in other sunlight because being near a tornado—even the one you set on purpose to clear your land—will level you if you stand in the wrong place too long. The headlines didn’t love me for more than a week; that is their cycle and not a problem I need to solve.

But the important things stood.

I signed the last page that put the company back in my hand and immediately removed my name from the brand we had created together. I renamed it after the paper cranes I used to fold for Fallon at seven when the storm shook the windows: Crane & Co. We built a fund under it to bankroll women veterans who wanted to start businesses that did not require their lives to be a marketing angle. We staffed it with people whose eyes do not slide off pain. We posted no photos unless the person in them wanted to be seen. We sent checks that made no content.

Vera moved into the office next to mine on a Wednesday and rolled her eyes at my plant choice. “Succulents are just cacti in PR,” she said. I kept the plant and hired her a data team that makes bankers sweat. Miles brought a bottle of something old to the office at eight p.m. one Friday and we drank it out of coffee mugs while we printed the last policy Fallon had written and set it on fire on the balcony. Clara framed the first grant check to a woman named Bri and hung it in the lobby with tape because we forgot a hammer and used what we had.

Rowan pled down in the criminal case after the IRS decided they wanted to write his middle name in their book. He will not go to Aspen again for the kind of weekend men buy and call a vacation. He will sit with probation so tight it squeaks. Fallon fights every subpoena like a person who still believes she can out–photograph the law. She sells a line of wellness candles under a name that tastes like sugar and bleach. People who want to be near good lighting buy them. They will forget. The courts will not.

I ran into my mother at the farmer’s market in June. She looked like someone who had learned to sleep with a light on and found out it doesn’t make nightmares hush. She reached for me, then did not. “You were always so stubborn,” she said, like an apology hummed under a breath. “You were always so sure,” I said, not making it either. We stood there two women who made other women. I did not ask for her side of anything. There is no side to a push; there is the ground and whether you hit it.

When I walked away, a girl with a ROTC patch on her backpack jogged up. “Sergeant Thornne?” she said, breathless. “I… saw the video. And then I saw the talk you gave at the community center. My sister told me I couldn’t. You know.”

“You can,” I said. “And if you don’t, do something else equally hard. But make it your call. Don’t fall for anyone who wants to push you off anything and call it love.”

She nodded and bit her lip and walked into the crowd with her shoulders an inch taller. Small victories; real ones.

I don’t think in endings anymore. I think in thresholds.

When the leaves went gold on the aspens again, I took a helicopter ride. You probably think that’s madness. My therapist calls it exposure. I call it not letting my sister own the air. The pilot had a laugh that made the headset crackle. He went up and stayed level and leaned over left so the trees laid down into a quilt of silver threads and green. I wasn’t brave. I was breathing. That counts.

At the top of Ridge Seven, there’s a branch I would pick out of a lineup in any forest. I should buy it flowers. It kept me in this story. I pressed my palm to it and said thank you to bark. The mountain didn’t answer. Mountains don’t care about justice. They care about gravity. It is enough.

On the guest room dresser at my house sits a paper crane with a bent wing and a gold foil sticker for an eye—a gift from a kid at the community center who makes armies of hope out of copy paper. Next to it is a photo someone snapped at the courthouse of me with my head tipped back in a way that reads as laughter but was actually wind. I keep them there as proof. One of paper. One of air. Both of choice.

The last line belongs to nobody. Not Fallon, not Rowan, not grief, not me. It is a question I promised the woman in the mirror I’d keep asking: Are you done apologizing for surviving? Every morning the answer is a little louder.

Yes.

Part Two

I didn’t sleep much after the “Yes.” — the small vow I gave the mirror instead of a victory speech. Peace wasn’t a switch; it was a muscle. The next morning, the district attorney’s office called.

“Ms. Thornne,” the investigator said, voice measured but kind, “we’ve reviewed the evidence you and your counsel provided—the financials, the storage unit documents, the footage from the funeral steps. We’re opening a criminal case. Identity theft and wire fraud, obviously. We’re also coordinating with Search and Rescue and Aviation on the ridge incident.” A pause. “We’ll need your testimony.”

“Tell me when,” I said.

“Soon,” he replied. “And Selene—bring the suit you wore yesterday. You won’t need armor. You’ll need to be seen.”

Criminal court is different than civil—colder, with rules that move like checkpoints. On the morning of the pre-trial hearing, a wind had dragged all the clouds away, and the city looked too clean for what was about to happen inside. Vera and I walked in with Miles; Dante joined us with a nod that looked like a reassuring weather report. Clara sat in the second row, jaw squared because she’d already decided not to flinch. Aaron hovered in the back like a man determined to hold himself up with apology.

Rowan pled “not guilty” through a jaw that forgot how to unclench. I watched the tendons jump under his skin. He avoided my face. I didn’t offer him the mercy of a look. His lawyer requested a continuance; the judge denied it. The streamlined version of justice started batting docket numbers at us before we finished sitting down.

Fallon entered third, wearing a soft blue sweater and the practiced expression of a woman’s magazine cover called Grit. The scrape that had lived under my ribs since the ridge eased—the body recognizes camouflage, even when it’s cashmere. She sat. She didn’t turn around.

The DA outlined counts like a recipe with every ingredient measured and leveled: one count of aggravated identity theft; three counts of wire fraud; two counts of making false statements to receive federal benefits; and a charge that made the courtroom inhale quietly in unison: attempted murder. The ridge wasn’t just a story anymore; it was a place with coordinates and a flight log and a pattern of wind recorded on a forestry station’s data file.

At the table, Fallon lifted her chin high enough to hurt. Her new attorney—fourth one—whispered and slipped a hand over the mic. When they say your name in that tone—formally, thoroughly—you are no longer the story you wrote for yourself. You belong to the record.

Afterward, on the courthouse steps, microphones sprouted from fists like flowers, but I didn’t stop. I owed the crowd nothing. I owed myself quiet between battles. In the car, Vera handed me a bottle of water and said, “We’ll pace this. You don’t have to go to every hearing.”

“I know,” I said, and realized I meant it. I had come far enough to choose my battles without a judge.

The company wasn’t something I could set down to pick back up later. Crane & Co needed decisions. All the tall words—integrity, transparency, restitution—need people to type them into QuickBooks and approve invoices. I spent mornings in glass conference rooms and afternoons in the community wing with women who knew what it costs to say start at thirty-five with a kid on your hip and no one clapping. Nights I walked the miles my body needed to burn the day out of my muscles.

We built a policy that said: you don’t get to borrow anyone’s story for money. It sounds obvious until someone offers you a sponsorship shaped like a trap. We refused all speaking invitations for six months. I told our PR manager to lock the press inbox unless a journalist had a FOIA request in their history. Meanwhile, Vera’s team audited everything. We cut off vendors with handshake agreements in back rooms; we started signing only if the person across the table could survive a Google search. It was boring—God, it was boring—and holy in the way tedious things can be when they lay punishment at the feet of people who think the rules are optional.

The scholarship we started—quietly, without hashtags—wrote its first ten checks. We bought a dental hygienist’s tools for a woman who had patched her life with Craigslist shifts. We paid a deposit on a food truck license for a former Army cook whose tamales made accountants cry. We covered community college tuition for Bri, the ROTC girl with steady eyes. When I handed her the envelope, she didn’t cry. She stood two inches taller. Sometimes money does that; sometimes money can be good.

Every so often, strangers stopped me on the street for the kind of small exchange that knits a life back together with a thread so thin you almost miss it:

“You’re the one from the scaffolding screen.”

“Yes.”

“Thanks.”

“Okay.”

It never got easier. It got truer.

Rowan folded first. Men like Rowan don’t like playing second in a story. The DA dangled the only power he had left: testimony.

When he asked for a meeting, Miles said, “Only with a full proffer and a prosecutor in the room.” I sat at the end of the table while Rowan spoke through his lawyer, taking my husband’s choices out of his mouth and making them sound like weather again.

He told them where the idea bloomed—Fallon’s couch, wine glass, my name on a legal pad next to a dollar sign; the afternoon they sat with a “consultant” who explained how to manufacture “continuity language” and a “protective filing” for mental incapacity; the day he typed a draft of the e-mail to the board with the subject line In the event we lose Selene and thought naming it would keep it in the realm of hypotheticals; the morning he held open the helicopter door and did nothing.

When the prosecutor asked why, he shrugged in a way that landed like a confession. “She makes gravity look like choice,” he said, eyes flicking sideways to Fallon’s empty chair. “I… liked being chosen.”

When he said it, something that had been hooked into my spine a long time slipped loose with a quiet apology. I didn’t forgive him. I didn’t tie it back on, either.

He took a plea: conspiracy to commit wire fraud; aiding and abetting identity theft; restitution north of any gated driveway. No prison; no passport. Five years of probation; five years of “No, sir, you can’t sit on that board.” He has to do two hundred hours of community service in a financial literacy clinic. Dante laughed until he had to sit down.

“Make him teach ten women how not to cosign,” he said. “That’s justice.”

Fallon ran out of attorneys who believed her retainer could redeem them. She stopped staging bookstore grief with sweaters and posted nothing. When she finally walked into the courtroom where the air we shared had none of the scent she had bottled and sold for $135 a spray, the prosecutor began with the tape she called a toast, not a confession, and the judge called evidence.

At the back, my mother came once. She wore a scarf with a print like iris petals and looked like she was trying to remember the rules for how to hold her hands in public. When Fallon glanced up and saw her, she didn’t soften. She hardened. That, somehow, hurt longest: the knowledge that the little girl who had clutched paper cranes had matured in cruelty more than grief.

In testimony, I told the truth again: the rotor’s jump, the push, the branch, the teeth of cold, the ranger cabin, the radio saying my name with presumed soldered to it. The funeral; the projector; the line down the middle of fear and fury. I told it without metaphor. You don’t decorate statements when you’re under oath; you lay them brick by brick and step away.

Fallon’s lawyer asked if my memory might be colored by trauma.

“The push wasn’t a metaphor,” I said. “Gravity doesn’t care about trauma.”

He asked if I’d ever told Fallon I felt in the way.

“I told her I wouldn’t move aside for her lies,” I said. “That’s different.”

He asked if I wanted to ruin my sister.

“Ruin arrived with ten digits in a payout line,” I said. “I’m just telling the air how it moved.”

Sentencing came on a morning so blue kids drew it with one crayon. The courtroom was full of ordinary people doing ordinary jobs with extraordinary attention—clerks and a bailiff and a man who changed a light bulb quietly in the corner while the judge spoke. Wire fraud: guilty. Identity theft: guilty. Attempted murder: the jury couldn’t agree on intent; Colorado intent is a tricky shape to hold. The judge sentenced her to eight years on the federal charges, three supervised release, and restitution so precise it read like poetry written by auditors.

Every system retains some flawed beat. I did not get the full chord my bones wanted. I got enough to stop humming the same bar in my head.

Fallon looked at me once while the judge read the numbers. She didn’t cry. She made the same face she made when I beat her time in the sixty–yard dash in junior high: an assessment, a recalculation, a resentment she called ambition and sold for applause. I did not mouth anything back. I didn’t know what language we had left.

After, on the courthouse steps, a young reporter who had done her homework and not tried to trade kindness for a quote asked quietly, “How are you going to spend the first day no one owes you anything?”

“Breathing,” I said. “Making coffee. Buying a lamp.”

She smiled like that was permission she needed to hear.

I didn’t become a motivational speech. I still got tired. People still wanted a piece of me they hadn’t earned. There were still nights I woke with wind in my throat and had to go stand on the balcony and count to one hundred while the city exhaled underneath me. Healing, it turns out, is municipal—work done quietly in a thousand small places.

The ridge didn’t call me back. I called it. Vera came with a thermos and a pack of gauze “because I’m superstitious” and because she loves me. We hired the same pilot who had taken me up to let air be air again the year before. He didn’t comment on the case; pilots don’t.

At Ridge Seven, I stepped out and walked to the tree. The branch was ordinary the way miracles are when your life has calmed down enough to recognize them. I pressed my palm to bark and felt gratitude move through my skin like warmth. I tied a crane to a lower branch with twine. White. No ribbon. The wind toyed with it and left it be.

“Let’s go home,” I told Vera, and meant our office and my apartment and the community center and the diner that still serves coffee older than some laws.

On Monday morning, Crane & Co’s grant squad had ten new applications on the top of the stack. A woman named Lila wanted to buy a food dehydrator for a trail snack business she’d dreamed up on bivouac. A Navy machinist wanted to retool a shop for bicycle repair. A former Air Force linguist wanted to start a translation co-op. We funded six, introduced four to one another, and told all of them the same thing: your story is yours. Spend it as you see fit.

A week later, I found a letter in the mail slot with handwriting so careful it made my chest tight. It was from Bri—the ROTC student. She enclosed a photo of a paper crane. For your desk, she wrote. From the girl who saw you not die and decided to try living louder. It went next to the light blue Post-it with Vera’s handwriting that says Breathe. The arrangement looked like a shrine to common sense.

I ran into Rowan once on a sidewalk near a courthouse I avoid now that the requirement is gone. He had a file under his arm and eyes that didn’t know where to land. We paused the way two people do when they share a history and none of it is fit for air. He said my name like a question he was not allowed to ask. I nodded because I reserve cruelty for people still trying to shove me. He stepped aside. The choreography of remorse.

My mother wrote a letter a year later. It wasn’t an apology; it was something softer and more frightening: a memory. You used to read to Fallon under the table during thunderstorms. There was a postscript. I’m learning not to choose the loudest child. I didn’t write back. I put it under the paper crane in a place where memory and promise look at each other and don’t blink.

At the community center one evening, an exhausted woman with a toddler and a sense of humor asked, “How do you stop being angry?”

“You don’t,” I said. “You point it at something on purpose. You don’t let it run the house.”

She nodded like she could carry that.

I’m not big on blessing people, but if I had one for you, it would be this: may your truths be dull enough to live with; may your boundaries be boring; may your drama be only in the books you choose to read. And if the day comes when someone you love becomes a cliff, may you catch a branch. May you say “not today” with your teeth. May you learn to make coffee the next morning, even if your hands shake.

“Ready?” Vera asked the afternoon we installed the sign with our new name on it. It didn’t light up. It didn’t need to.

“Yes,” I said.

I still say it sometimes, to the mirror over the sink, to the branch, to the paper crane, to the woman who almost didn’t walk out of a funeral she didn’t deserve. The word isn’t a war cry anymore. It’s a key. It unlocks only the doors I choose.

END!

News

Can you even afford this place? My sister sneered loud enough for nearby tables to hear. ch2

Can you even afford this place? My sister sneered loud enough for nearby tables to hear. She laughed, sipping her…

My parents left me at a train station as a joke. Let’s see if she can find her way home. ch2

My parents left me at a train station as a joke. Let’s see if she can find her way home….

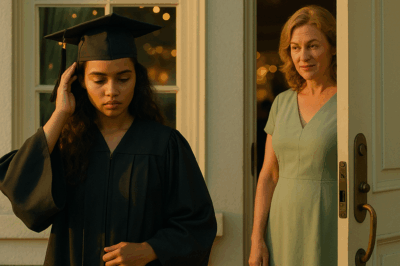

At my graduation party, I was told to wait outside the venue. My aunt smirked, “This is just for close family.” ch2

At my graduation party, I was told to wait outside the venue. My aunt smirked, “This is just for close…

Walk it off. Stop being a baby,” my father yelled as I lay motionless on the ground. My brother smirked while mom accused me of ruining his birthday. But when the paramedics saw I couldn’t move my legs, she immediately called for police backup. The MRI would reveal. ch2

Walk it off. Stop being a baby,” my father yelled as I lay motionless on the ground. My brother smirked…

When I got married, I kept quiet about the $25.6 million company I inherited from my grandpa. Thank God I did because the day after the wedding, my mother-in-law showed up with a notary and tried to force me to sign it over. ch2

When I got married, I kept quiet about the $25.6 million company I inherited from my grandpa. Thank God I…

My family made me take the blame and the beatings for my siblings mistakes, calling it tradition. When I finally exposed my father, the so-called hero, he twisted the story and convinced the whole town that I was the villain. ch2

My family made me take the blame and the beatings for my siblings’ mistakes, calling it tradition. When I finally…

End of content

No more pages to load