My sister paid my crush to reject me. She didn’t know his billionaire father wanted me to marry his son.

Part One

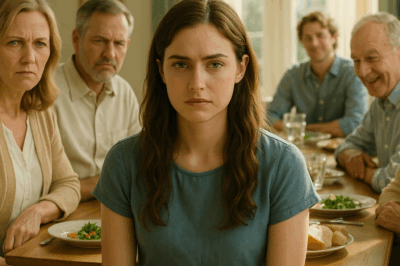

The first thing people always ask is whether I cried. I didn’t—at least not where anyone could see. I stood there with a paper crown askew on my head and a frosting flower sliding off the side of a cake with my name piped in the wrong shade of pink, and I did the math in my head the way I always have when the room turns on me: distance to the door, seconds until the song ends, how much of me they get to keep.

It was my thirty-second birthday party, which in my family meant my younger sister Rachel’s promotion party. She clinked her glass, basked in the warm light of my parents’ living room, and raised a toast to herself—“to climbing every ladder and breaking every ceiling,” a line she must have practiced, complete with the dramatic head tilt. The crowd laughed in all the right places. The new luxury car my parents had surprised her with sat in the drive, a silver punctuation mark to a speech about grit she’d never needed to use.

I could have swallowed that. I have for years. But then Rachel found Ben by the dessert table, put a perfectly manicured hand on his shoulder, and said in a voice meant to carry, “Just tell her how you feel. Be honest.”

Ben turned toward me. His face took on a look I didn’t recognize, something cold and performative. His eyes skimmed me like I was a caption he needed to read quickly. “Leah,” he said, loud enough for the room to quiet, “I need to be straight with you. I could never be interested in someone so unambitious.”

The laugh came from my father first. Then my mother. Then the room. I stood there with the paper crown and the too-sweet cake and felt the old ache move through me like a familiar draft: the summer I won a place in a national entrepreneurship program and my parents called it “a camp”; the fall I worked two jobs to finish my degree while they paid for Rachel’s out-of-state art school and an apartment with crown molding; the winter I asked for a small loan to launch a prototype and watched them write a six-figure check to fund Rachel’s glossy online boutique that folded in a year. The pattern had never been subtle. It was just louder now, with witnesses.

If you’ve ever stood in the center of a celebration that wasn’t for you, you know the calculations the body makes to survive. Find a wall. Find air. Find a door with a lock that belongs to you. I set down my plate, walked past the laughter, and stepped onto the back patio. The night was cold enough to bite. I put my hands on the railing and breathed.

“Leah.” Ben’s voice, behind me. When I turned, he wasn’t smirking. He looked like a man who’d just realized the script he’d been handed would end in a role he didn’t want. “I—”

“Don’t,” I said. “Whatever excuse you’re about to try, don’t.” The hurt was a low throb, but my voice was steady. “I saw the envelope.”

He flinched. Later, I’d learn exactly how thick the envelope had been—five thousand dollars thick, from Rachel’s account to his in a neat wire earlier that afternoon—but in that moment, all I needed was the look on his face to confirm what I already knew. He’d taken her money to humiliate me on my birthday, and no backpedaling would shrink that.

“There’s something you need to know,” he said quickly, words tumbling over each other in a way they never did when he had a racquet in his hands and a court to own. “My dad—”

“I don’t particularly care what your dad thinks of me,” I said, and I meant it—then. “I care that you took money to turn me into a joke.”

Ben’s jaw worked like it had learned a new trick and wasn’t sure when to show it. “Leah, please. It wasn’t—” He stopped, exhaled, and shook his head. “Fine. I’m sorry.”

It wasn’t fine. I went home early. I brushed frosting off my dress and the smell of someone else’s perfume out of my hair and sat on the edge of my bed with my shoes still on, turning my phone facedown every time it lit with a new message from my mother (“Don’t be dramatic”) or my father (“It was a joke”) or Rachel (“Lighten up, you make it weird”). I could have blocked them then. Instead, I opened the message from Ben that arrived just after midnight.

I shouldn’t have done it.

My father wants to talk to you.

I laughed, then, alone in my apartment. The idea that the man who’d raised the boy who had humiliated me would want to talk felt like a punchline I hadn’t learned how to deliver. I typed one word back because I wanted him to feel the economy he’d denied me in front of that room.

Why.

Because he believes you’re the person he’s been looking for.

Not just for me. For the company. For everything.

Please. Coffee tomorrow. His office. 11.

If you’ve ever had someone you care about sell you for the price of their convenience, you learn to be careful with second chances. I almost said no. I said yes because “no” is best used on a person you will have to see again, and I planned not to.

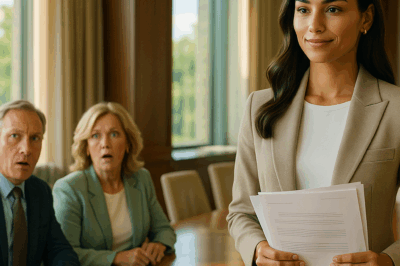

Arthur Hayes’s office was three floors below the top of a building that had his name on it. The windows framed a city that had never felt like mine. He did not stand when I entered. He did not gesture to the chair. He looked at me like he was comparing me to a list only he could see, then inclined his head once, sanctioning me to sit.

“Ms. Cohen,” he said—a detail people miss when stories get told about tall men and their tall money. He knew my name and how to say it. “Do you know who I am?”

“Of course,” I said. “The question is whether you know who I am.”

He smiled, but it didn’t reach his eyes. “Good. You don’t waste time. This is the part where I am supposed to apologize for my son.” He folded his hands on the desk. “I won’t. Not on his behalf. He needs to do that work himself.”

“Then why am I here?” I asked.

“Because I have been looking for someone for two years,” he said, “and last month I realized she was right in front of me.”

He spun his monitor to face me. Security footage, high definition, dated the week before. Rachel, in a dress I recognized from my mother’s Instagram, across from Ben at a table that tried too hard with its light fixtures. She slid the envelope across the white linen. The camera caught the tilt of her chin, the rehearsed concern in her voice. The audio was perfectly clear.

“Tell her in front of everyone,” she said. “Something she’ll remember.” A pause. “Something about… ambition.”

On the screen, Ben’s face did the thing I had seen the night before. “This is low,” he said.

“Worth five thousand?” she said. When he didn’t answer, she tucked a strand of hair behind her ear. “Consider it… compensation for the years she’s wasted everyone’s time.”

Arthur clicked pause and then opened the next window: a bank statement showing the transfer from Rachel’s account to Ben’s. He clicked one more: a digital folder full of photos of me at a charity tech gala three months ago, standing with Arthur himself, with women he mentored, with a whiteboard full of sketches for a project I’d pitched to a room that hadn’t laughed.

“I started following you that night,” he said. “Not because of who you were standing next to. Because of the way you asked the only question that mattered and didn’t wait for permission to ask it. I’ve watched your work. I’ve read your proposals. I have a son who has the parts of me I wish I didn’t, and a company that needs the parts I don’t have.”

“What parts are those,” I asked, even though I’d started to understand.

“Vision that doesn’t mistake shine for substance,” he said. “The willingness to say no, loudly, in rooms trained not to hear it. And an appetite for building something that will outlast the rumor that gets told about how you got there.”

He let the silence stretch. “I want you to marry my son,” he said finally, like the sentence had muscle memory from a different era, “only if you want him,” a clause he added like a man whose muscles had learned different work late in life. “But regardless of that, I want you to marry this company.”

I laughed, then—this time on purpose. “That’s a very flattering metaphor for a job description,” I said.

“It isn’t a metaphor,” he said. “It’s an acquisition. Of me. Of Ben. Of everyone who has mistaken your quiet for absence. If I asked you to join me—publicly—would you?”

A lot of people build revenge around a reveal. They plan a message that makes the room gasp and then pay for breakfast the next morning with an empty card. I didn’t need a spectacle. I needed leverage. Standing in Arthur Hayes’s office with the city folded under his windows like a map, I realized he was offering me both.

“I’d have terms,” I said. “I’m not a prop in your family’s attempt to sanitize its heir. I lead on my own name. If Ben and I choose each other, that’s ours. The company is separate.”

He nodded like he’d been waiting for the distinction. “Good. You’ll need separate contracts. And a prenuptial that would make my lawyer cry tears of clean lines.”

I went back to my apartment with a folder thick with documents and a new tautness under my skin that wasn’t fear. For two weeks, I let my family do what they do. My mother posted photos of Rachel posing with that new car. My father talked about dinner with “the Hayeses” he hadn’t had. Rachel sent me a link to an article about executive dressing with a note that read, “In case you ever want to level up” and a wink emoji that belonged to someone twelve.

Arthur and I met three more times. Once with lawyers, once with people who would report to me if I said yes, and once with Ben. He came into the room looking like he wasn’t sure his legs would obey him. He didn’t try to sit across from me. He sat next to me, like a person who’d learned a thing about direction.

“I’m sorry,” he said, before Arthur got two steps past the door. “No qualifiers. No price tag.”

“I can hold that and still not forgive you,” I said.

“I know,” he said. “I’d like to do the work that would make forgiving me a thing you might not hate.”

It wasn’t a line. He didn’t try to earn absolution with proximity. He showed me a notebook full of ideas and crossed-out arrogance and times he’d gotten it wrong. He sat through a meeting where a woman ten years his junior explained a piece of code he’d pretended to understand for months, and he didn’t interrupt to remind her he was in the room. He asked me to walk with him at the end of the day, and when we got to the elevator he said, “I will never be the cost of your competence or the reason you leave a room.”

“How romantic,” I said dryly, but I felt something unclench.

We picked a date. Not for a wedding—those come after learning a person without a press release in the middle—but for a shareholder meeting. Arthur liked a long game; I preferred a short one with momentum. The meeting would do both. He’d announce new leadership. There would be a section on “values” that wasn’t performative because we’d back it up with contracts. And, because some people only understand consequence when it is illuminated by a projector, we would show a video.

The night before the meeting, my mother texted. VIP row! We got our passes! As if the words meant the same thing for her that they did for me. I wore a navy suit I chose because it made me feel like someone who could walk on a stage and say the real thing without curling at the edges. I stood in the wings with Arthur and kept my breathing even while the warmup music played the kind of music that tries to make capitalism feel like a heartfelt confession. I didn’t have to wait long.

Arthur went first. He had a way with a room that made you forgive him the people he had stepped on to build it. He talked about market share and R&D in a way that made both sound like the beginning of a story instead of its end. Then he said, “Our greatest asset is not a line item. It is the person who created it,” and invited me to the stage.

If you’ve ever spent a life shrinking in doorways so your sister’s dress can take up more room, you know what it feels like to walk straight down the center of a line of chairs and not apologize when your shoulder grazes a seat. The lights were hot. The screen was a rectangle of light waiting for a narrative. I stepped up to the podium.

“My name is Leah Cohen,” I said, finding myself in the vowel. “You’ve never heard of me. That’s by design. I build the things the room uses to look at itself. I’m here to tell you I’ll be building them with you now.”

I talked about the work. Not for long. Not in a way that hid behind jargon or the kind of ambition that eats its young. I drew a picture that made money and meaning fit in the same sentence without choking each other. Then I stepped aside.

“And because values without enforcement are just slogans,” Arthur said, “we want to be transparent about why we’re making changes now.” He gestured to the screen. The video played. Rachel’s envelope slid across the linen. Ben’s face did its dumb dance. Rachel’s voice said the thing she won’t ever be able to swallow back down.

There are people who think public humiliation is a cheap gimmick. They might be right. I didn’t put that video up for me. I didn’t need it. I was on the stage without it. I put it up because my parents operate on one currency: shame withheld from everybody but me. I chose to trade in it for a moment to reset the exchange rate.

The room murmured. It didn’t gasp. The world has seen a lot. Arthur didn’t look at me for approval. He didn’t need to. He looked at my parents in the front row and said, “We do not do business with people who mistake cruelty for competence,” and something like a wave moved through the room.

Two rows back, Ben swallowed and stood up without prompting. “I knew better,” he said, into the mic the stagehand didn’t want to give him. “I did it anyway. I’m doing my penance where my father can keep an eye on me. And I’m grateful she’s willing to let me sit in rooms like this again.”

The fallout was ugly in a way I didn’t enjoy, which is how I know I hadn’t done this for the spectacle. My mother’s face went white with a particular shade of fury that had once been reserved for waiters who didn’t refill her water quickly. My father tried to stand. Security asked him to sit. Rachel held it together for longer than I expected, which is to say until her seat made a sound when she moved.

After, Arthur and I signed some papers far away from cameras. I signed a contract that gave me the authority and insulation I wanted, not the bright shiny thing people expect. There was a call with a board that went the way calls go when money is in the room plus someone who knows why it’s there. I went home and took my shoes off and stood with my toes sinking into a rug I bought myself with money I made writing for machines that ended up making things easier for people.

Ben called me later. “I wanted to be the person who protected you from that,” he said, “not the reason you needed protection.”

“You can be the person who carries desks,” I said. “This place is moving.”

He laughed, not because it was a joke but because he had breath to. “Where do you want to go first?”

“Out of the room where I’m someone else’s story,” I said.

We didn’t get engaged that night. Or the next. We went to dinner a week later at a place where nobody knew me, and he asked me more questions than he answered. He put his phone face down not like a performance but like a person who has finally learned that a body sitting across from you is the thing that holds your life together. When he kissed me outside the restaurant, he didn’t taste like someone who was trying to buy absolution. He tasted like rain held at bay by a well-made tent.

By the time my parents called the next morning, the shape of things had changed enough that my body didn’t go into its old panic. “We need to talk,” my mother said, as if the language belonged to her.

“We don’t,” I said. “You need to apologize. Publicly. Then we’ll talk.”

She sputtered. My father tried a different door. “Let’s be reasonable,” he said. “That was a private matter.”

“You paid a man to humiliate me,” I said. “You made it a public matter. You don’t get to hide while I mop your mess.”

They didn’t apologize. They also didn’t get to use my name as a discount code around town anymore. They learned the economy of respect the oldest way: at the grocery store checkout.

I built a fund for girls who can’t get into the room with the whiteboard because their mother needs to use the car. I wrote checks to a community center to rent a van that would pick those girls up in the morning and drop them home with a calculator that belonged to them. I got on a plane to a city where a manager at a factory I’d never heard of let me watch a line move with the grace of a ballet, and I came home and wrote a program that made it safer for the man with the left knee that clicks to bend one fewer time an hour. I sent an anonymous donation to an entrepreneurship camp with a note that said, Build ladders. Not crowns. They emailed back to ask if I wanted my name on something. I said no and then went to sleep like a person with a full life.

I also married the man whose father once thought he could sell a future. We did it in a room without a projector. My dress didn’t need a name on the label for me to feel like myself. Arthur cried—not the kind of crying men do when they think someone is watching. The kind that surprised him. Rachel didn’t come. My parents did, and sat in the second row because the first was for the people who held me when I didn’t know if my work would outlast a rumor.

After the ceremony, my father stood up at dinner. He didn’t clink a glass. He didn’t prepare a speech. “To Leah,” he said, as if saying it correctly might build a new muscle he could use later, “whose work changes rooms.” He sat down before he made it about himself. My mother placed her hand over mine, a gesture from a language we both still struggle to learn, and said, “You look like you built this dress,” which might be the closest I’ll ever get to I’m proud of you and, honestly, might be better.

There’s a difference between villains losing and you winning. One makes for a good story you can tell once; the other builds a life you live every day. The first time someone mistakes you for the girl who got laughed at next to the dessert table, it will take everything in you not to turn around and show them a video. Don’t. The payoff is in saying, “I’ve got a meeting,” and walking away to do the thing no one can take from you because you built it with both hands.

When the paper crown finally fell off my head, I left it on the kitchen counter for a week. A reminder of the rooms I don’t stand in anymore and of the ones I do. On the eighth day, I put it in the recycling, took out the trash, and went to work.

Part Two

Arthur liked to say that the only kind of dynasty worth building is one where the successor could sue you and you’d still show up for Thanksgiving. I used to think it was a line. The first Thanksgiving after the meeting proved it was a principle—messy, human, stubbornly applied.

Ben and I hosted. Not because I needed to prove anything, especially not in my own kitchen, but because I finally wanted to see what “family” looked like without a spotlight and a script. We set two tables: one for food, one for laptops, because half the room was on-call for a product we were unrolling in a country that refused to keep time zones convenient for Americans. We invited my parents and Rachel and expected nothing from any of them beyond minimal decency. That’s about what we got.

Rachel came late. She wore humility badly, like a dress bought in haste. She hovered by the door until I nodded and then went to stand in the place where a person stands who wants to be seen without being asked to explain how they’ve changed. “I’m trying,” she said, into my shoulder when we hugged. “Not because you won. Because I’m tired of losing myself.”

“I can’t manage your effort,” I said gently. “I can only manage my door.”

She nodded. “Your door has better locks now,” she said, which was both small talk and a metaphor.

Mom brought mashed potatoes that tasted like the ones she made when I was eight. She set the bowl down like an apology and then bustled in a way that suggested bustling could build a bridge between what she’d done and who she wanted to be. Dad carved the turkey with a focus that would have served him well at more than one business meeting. He didn’t give a speech. He carried plates.

At some point, my phone buzzed with a message from a number labeled only Facilities. The subject line read: “Load Test Success. Closing ticket. Great work.” I didn’t open it. Ben looked at me and raised his eyebrows. “Sit,” he mouthed. “Eat.”

The weeks that followed had that rare quality of post-reveal life that stories don’t know how to tell because they think the end of a thing happens when the video plays. Work input became output. The women in the girls’ fund submitted expense reports for gas and childcare that read like a poem about what the right hundred dollars at the right time can do. My inbox became a weird split-screen of Fortune 100 company CEOs and high school teachers. I met with both and came home equally energized.

Arthur and I established an uneasy peace that deepened into something warm. He still had the reflexes of a man who’d considered a hostile takeover a romantic gesture, but he learned to laugh at himself before I had to. He took to emailing me articles at 3 a.m. with subject lines like “In case you wanted to be angry before breakfast,” and I learned to reply with “Consider this your overtime donation invoice” and a link to a school that needed a lab.

In quieter hours, I sometimes went back and watched the recording our internal team had made of the shareholder meeting. Not the video. Me. I studied the way I moved through that moment. I took notes, not as an exercise in ego but as a way to teach myself how to stand in the rooms I build next without shrinking to fit a chair I no longer sit in. I showed that video to a room full of women at a conference—no glitter, no “girlboss”—and told them the thing no one tells you when they sell you ambition: you don’t need to learn to be loud. You need to learn to be full.

My parents did not regain their money. They did, slowly, earn a different kind of credit. Dad, who had once measured his days in transactions and headcount, started volunteering at the fund. He did intake interviews for applicants who wanted to launch micro-businesses and learned that questions that work in a boardroom will wither a person whose bank account has been empty more than full. Mom made snack bags. She kept her hands busy and her mouth something less than busy, which for her is a form of prayer.

The one truly cinematic moment of that year didn’t happen on a stage. It happened at a plastic-folding-table graduation ceremony in a gym that smelled like old sweat and sanitizer, where a girl named Litzy in a red cap took the mic and said the line that ended up finally cutting cleanly through the scar tissue around my heart.

“My mother wanted me to marry a man with a name,” she said. “Instead, today, I married my name to a business license.”

She pointed at the fund’s banner. “I can do that because someone built a staircase and then sat on the bottom step and said ‘okay, your turn.’” We stood and clapped and then later helped roll the bleachers back into the wall.

Rachel found her way to those rooms slowly. She started with menial tasks—printing, coffee, stapling—because sometimes you need to remind your hands they can make something besides a mess. She shook in the way of a person who hasn’t been trusted by anyone in a long time, and then one day she stopped shaking and started speaking in ways that made more sense. She apologized to me in a room where other people could hear it and then again in a room where they couldn’t. I accepted her apology with a clause: “When you feel small again, don’t make me smaller to keep yourself company.” We learned to catch each other before the old shape formed.

The last conversation with Ben that mattered did not start with “I love you.” It started with, “I signed the paperwork,” and then he handed me a copy of the prenuptial agreement he’d insisted on, written to protect my company and any daughter I might have from the version of him that had dialed a bank account instead of a conscience. He wasn’t romantic about it. He was practical in a way that turned the word from something my father said when he wanted to flatten me into a compliment.

We did get married. Not in a ballroom. In a city hall that smelled like lemons and legal pads. The mayor’s assistant took our picture and said she hoped we’d make each other good. Arthur cried. My mother dabbed at the corners of her eyes slowly, as if reassuring herself there was something there to wipe. My father stood between a potted ficus and a poster about zoning and laughed when Ben almost dropped the ring. Rachel wore a dress she bought with money she made drawing flyers for a climate march. She looked like a person with fewer excuses and more hours of sleep.

After, we held hands in the back of a car that wasn’t a symbol and watched the city go by like the inside of a snow globe, glittering and contained. We didn’t make speeches. We made promises the sort that sit inside your teeth so you can bite down on them when it’s time to use them.

If there’s a lesson here, it isn’t that revenge tastes like champagne. It’s that justice tastes like water on a hot day, necessary and unremarkable and not something you stand in a room to applaud. People ask me what I would say to the version of me with the paper crown on her head and the frosting on her dress. I think I’d hand her a napkin and say, “Keep the crown if you like the way it catches the light. It doesn’t change your work.”

In the end, my family learned to sit through dinners without reciting our resumes. My father found a way to tell stories that didn’t begin with money. My mother started giving things away that weren’t mine. My sister learned to hand people envelopes with invoices inside instead of bribes. It was a good year to be wrong about everything and then to be brave enough to live inside the correction.

My name is Leah. I am thirty-three. I run a division of a company that used to think women like me were best used as decorations. I love a man who knows the most romantic sentence in our house is “I’ll take the 2 a.m. call.” I stand on stages sometimes, and when I do, my neck doesn’t tense when I say my name. I sit at plastic tables most of the time and pass out pens.

There are nights when I wake and the old video plays in my head. I let it. It reminds me the work is never a one-and-done thing. It is a system. It requires maintenance. You check the lines. You listen for leaks. You write a test and run it again in the morning.

And when the laughter from a room that didn’t want you once comes up from the street, you close your window because you already did your time in rooms like that. You have better places to be.

END!

News

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. ch2

I Was Tricked Into Becoming The Other Woman—And Then I Discovered A Truth Even More Cruel. But… Part One…

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me. ch2

I Took a Job Caring for a Dying Millionaire Widower. But When He Saw My Ex-Husband Humiliate Me… Part…

At The Family Dinner, My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong. CH2

My Parents Said: “You’re The Most Useless Child We Have,” But I Proved Them Wrong Part One The roast…

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. CH2

My in-laws called me a gold-digger until I bought the company that held their entire life savings. Part One…

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… CH2

My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed… Part One The hallway outside my…

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One. CH2

My Husband Left Me In The Rain To “Teach Me A Lesson”—But My Bodyguard Taught Him One Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load