My Sister Mocked Me At Dinner “Photocopier Captain?” — Then Dad’s Old War Buddy Saluted Me.

At dinner, my sister sneered: “Photocopier Captain?” Everyone laughed. Then Dad’s old war buddy — the same man she planned to beg for a huge favor — walked in, froze when he saw me, and gave me a salute. The room went silent.

Part 1

If you’ve never been laughed at by your own kin while you’re still holding the menu, count yourself lucky.

We were at Cavanaugh’s, the kind of Midwest steakhouse that pretends its mahogany is real and its tomatoes are local. My father—Tom Hale, retired electrician and Gulf War vet who still keeps his boots lined up under the bed like orders might come down at any minute—had turned seventy-two that week. My sister Madison wanted the dinner to be “classy,” by which she meant expensive and within earshot of people she hoped to impress.

“You’ll be there, right, Jordan?” she had asked, voice bright with the kind of cheer that usually precedes an invoice. “Dad’s friend is flying in. Huge deal for Brett and me. We’ll explain at dinner.”

Translation: show up, behave, and don’t get between me and whatever favor I’m about to ask.

I got there early anyway, because Dad likes not having to be the first person in the room, and because old habits die without meaning to. The hostess smiled with her mouth and not her eyes. A busboy adjusted silverware down the table like lives depended on it. I sat at the far end because Madison had taught me years ago that place cards are invitations for hierarchy.

“You could at least wear the uniform for Dad,” Mom said when she slid into the chair beside me, setting her purse down like a boundary. “He loves it.”

“I’m not in uniform anymore,” I told her. “And he loves me regardless.”

“I know,” she said, which is what people say when they don’t. “But it would have looked so nice in photos.”

My sister arrived with a wind behind her, perfume and a laugh that turned heads. Brett—her husband, a man who could sell suntan lotion in January—hovered, running a hand over his hair every time a waiter walked by. Madison hugged Dad as if she’d invented hugs. Then she hugged me, air and bone, her earrings cold against my cheek.

“You made it,” she said. “Good. Don’t be weird tonight.”

“Wouldn’t dare,” I said.

We ordered. Bread arrived. Dad held court modestly, like he always does—stories about the base in Kuwait, about the time a sergeant major made him laugh so hard he dropped a wrench on his own foot. Madison smiled like she was having the idea of a good time. Mom asked if I’d thought any more about switching to hospital administration “since those hours are so brutal on your face.” Brett nodded sympathetically and told me he’d heard “the VA will take anybody these days.”

I sipped my water and let the fizz lift my tongue because I’ve learned to keep quiet long enough to let people say exactly who they are.

“You still doing the—what is it?” Madison asked, twirling a straw through ice. “Photocopier Captain?”

Brett snorted. Mom’s mouth pinched and then tried to smooth. Dad’s fork paused midair.

“What?” I asked.

“You know,” she said, waving her hand in a circle near her temple the way people do when they’re excited to be cruel. “When you were deployed and you…did paperwork. You ran the office. You did…copies.”

A laugh hopped around the table like a stone on water. It didn’t matter whether it landed with one person or three; it landed. The thing about family is you can feel a laugh pressed into you harder than a slap.

“Adjutant,” I said, calmly. “S-1. Personnel and admin. Captain.”

Madison widened her eyes innocently, which has been her favorite trick since she was five. “Right. Captain of the photocopier. That’s what Brett calls it.”

“Because it’s funny,” Brett said helpfully.

“Because it’s ignorant,” Dad muttered, too quiet for Madison to hear and too late for it to matter.

I put my napkin on my lap and fixed my gaze on a framed black-and-white photo of cows above the hostess stand. Cavanaugh’s wants you to believe this city was built on cattle and grit instead of logistics and zoning permits. It’s a lie I sometimes let myself enjoy.

“Anyway,” Madison said, flapping away the moment. “Dad’s buddy is almost here. He’s the reason we picked this place. He loves their ribeye. He’s also the reason we’re going to have a very, very good year.” She leaned toward Brett. “Right?”

“Right,” he echoed, eager.

Mom smiled, the sun breaking through. “How is Bobby these days?”

“Colonel Ellison,” Dad said automatically, proud bending his vowels. “Haven’t seen him in twenty years. Saved my hide in ’91. He moved into defense contracting after he retired. He knows everyone.”

Madison tapped the table like a judge. “He’s on the board of the foundation running the city’s public-private grants. Guess who’s launching a coworking space-slash-creative studio for our startup?” She beamed at Brett. “We pitch him tonight. Favors for family.”

I stared at my sister—the audacity of her timing, the geometry of her selfishness. I could have told her the foundation she planned to charm had a vetting process with teeth. I could have told her the Colonel had a reputation for sniffing out grifters the way a dog finds a bone. I could have told her that the problems with her “startup” (a ring light, three MacBooks, and a vague plan to “elevate creators”) weren’t going to be fixed by a beef dinner and a winged eyeliner.

I did not. I broke bread and kept my counsel.

“At least your…what do you call it?” Madison asked me, bouncing again. “Your…service. That must have given you contacts. Right? That’s the whole point of the…service.”

I looked at my father. He looked at his hands.

“The point of service,” I said, “is service.”

Madison rolled her eyes. Brett chuckled. The bread tasted like paste.

The door opened behind the hostess stand and an old man stepped through the way old soldiers sometimes do—head up, back straight, as if gravity owed him a favor he didn’t intend to collect. He wore a pressed blue blazer and a tie with tiny silver jets stitched into it. A scar tucked itself just under his hairline and refused to apologize. Age had leaned a hand against his shoulder but hadn’t gotten him to bend.

“Bobby!” Dad shouted, half-standing.

Colonel Robert Ellison scanned the room the way you scan a horizon. His eyes landed on Dad, lit up, and then moved—past Mom, past Madison, past Brett—until they found me.

He stopped walking.

For a heartbeat—two—three—the whole restaurant hushed, as if a low pressure system had rolled in and the air needed to adjust.

Then he did something that made every fork in the room pause midair.

He stood at attention.

And he saluted me.

The sound in my head changed frequency. That’s the only way I can explain it. The old man’s palm cut the air sharp and clean. The scar on his temple went pale. His eyes were wet, and not from age.

“Captain Hale,” he said, voice steady. “Ma’am.”

You could hear glass settle from two tables over. A waiter breathed again. The hostess, whose job is to pretend nothing surprises her, clapped her hand to her chest and let it fall, embarrassed at herself, then defiant about the embarrassment.

Madison’s mouth slipped open. Brett’s laugh died like a light.

Dad made a sound I hadn’t heard from him since I was twelve and got my name called first at the science fair—something between pride and relief.

“Colonel,” I said, standing. My body knew what to do long before my brain did. I returned the salute.

We held it a second longer than protocol demands and not as long as I wanted. Then he let his arm drop, and I did the same, and the room remembered it was a room.

“Of all the gin joints,” he said, shaking his head, smile huge and shameless. He clasped my hand in both of his. “I hoped I’d meet you like this someday. Didn’t figure it would be over a ribeye.”

“Sir?” Madison managed, squeaky. “You—um—you know Jordan?”

The Colonel turned toward her, eyebrows sliding up. “Know her?” He barked a laugh. “Young lady, if I ever build a statue, I’m putting her clipboard in its left hand.”

Madison blinked. Brett frowned like math had stopped making sense. Mom sat very still.

Dad slid into his chair like his knees had given up for the night and his heart was trying to do twenty jobs at once.

Part 2

If you live long enough, you learn there are stories that go best with gravy. We ordered. The Colonel loudly refused the “healthy” menu, called the waitress “ma’am” in the old way that makes you forgive it, and asked Dad the names of the same half dozen men he always asks about before anyone gets to tell him they’ve all died or moved to Florida.

When the plates were promised and the wine had kissed the glasses, he cleared his throat and did what men like him have done in every American restaurant since D-Day: he told a story in sentences that marched.

“I was in D.C. late last year,” he said. “Doing the song and dance. Fund-raising for the foundation. Tour of the memorials. You know the drill.” He said it with the weary affection of a man who loves a thing enough to make fun of it. “Got invited to sit in on a commendation ceremony at the Pentagon. Small room. Quiet. Had the good sense not to call it a ceremony—just words in a room with coffee you can fix an engine with.” He smiled at me. “They started reading a citation. Captain Jordan Hale. It got my attention. Hale is a name I know.”

Madison blinked. “Citation for a—what?”

He ignored her kindly. “And they started in on details. Kabul. Airport. August. The kind of mess you don’t clean up with mops.” He lifted his napkin and set it back down, a small mimic of a flag being folded. “They said a Captain in S-1—logistics and personnel to the uninitiated—got tasked with the thing no one wants: names. Manifests. Buses. Numbers that add up to lives.”

He looked at me, gave me the floor, and I could feel the table tilt toward me.

“It was a lot of…paper,” I said, because I have never loved telling stories with myself in the middle of them. “A lot of people. Too many. Babies shoved at Marines because mothers believed America would hold them better. A list with errors means a family with a grave.”

Madison tried to remember how to breathe but didn’t find it quickly.

“The printer jammed,” I said, letting the corner of my mouth go up because if you don’t bend in a story like this you break. “Three times. The power cut twice. The comms went down because the generator overheated. I kicked the side of it until my boot hurt and then kissed it when it coughed back to life. You do what you can with what you have.”

The Colonel nodded, satisfied that I’d told the truth by leaving ninety percent of it out.

“What they read,” he said, taking back the baton, “was the part most folks forget because it doesn’t look heroic in a movie. It looks like a woman sitting on a busted office chair sweating through her blouse, holding a phone to one ear while a staff sergeant yells over his shoulder that he needs twelve more names fast because the bus is about to go and the man at the gate has a gun he doesn’t know whether he wants to use.”

He took a breath.

“The part they read was the list. The right list. Twice. Numbers married to faces. The manifest matched the seat count. Because she’d fixed the damn printer with a bobby pin and a prayer.” He grinned at me like he wasn’t supposed to know about the bobby pin. “Because she knew if the numbers were wrong, my boy would have stayed outside that wire another hour and one of the hours that followed was a bad one.”

Silence. And then Dad, quietly: “Your boy?”

The Colonel nodded. His knuckles had gone white around the utensils. “Sergeant Ellison. Rear gate. He sent a message that night. Said a Captain with her hair in a mess and grease on her face told him they had room for one more bus and he’d better get back to the line because she’d been saving him a seat for an hour and was about to run out of breath from yelling.”

He looked back at me. We didn’t need to ask how he knew about my hair. The Army is a smaller place than it wants you to believe.

“He made it,” the Colonel said, almost apologetically, like good news was somehow rude. “He made it because you can call it paperwork if you’ve never seen work make its way onto paper and keep a human breathing.”

Madison’s hand went up to her mouth. Brett swallowed so hard I heard it. Mom finally let the tears she’d been holding fall, one and then another, clean lines down her face. Dad sat straighter in his chair and didn’t try to dry anything, and I loved him twice for both choices.

Madison started to say something like a joke and thought better of it. She took her hand down. Her face looked naked without the smirk.

The Colonel glanced at the bread basket and then at Madison. “I hear somebody made a photocopier joke.” His voice stayed easy, but all the parts of it got older suddenly, like wood in a house you didn’t maintain for a few years.

Madison looked at her lap. “I—well—we—”

“You know what they call admin officers in every unit worth its salt?” he asked.

No one answered.

“Irreplaceable.” He smiled again, friendly as a sunrise and sharp as a winter morning. “You think wars are fought with muscles and guns. And they are. For about ten minutes. Then you run out of something. Fuel. Food. Names. And you call a captain like her. And you pray she answers.”

The waiter arrived with steaks as if on cue, poor man. He set plates down around the edges of a conversation he didn’t want to be in. The sizzle on the cast iron sounded like applause nobody would dare offer out loud.

Madison made a little gathering gesture with her hands, the international sign for time to move on and talk about funding again. “Colonel,” she said brightly, “we are so excited to—”

He held up a hand. She stopped. It wasn’t rude. It was a mercy.

“Thomas,” he said to my father, as if we were back at the VFW in 1998 and the same song was playing. “You raised good. You didn’t have to. A lot of men don’t. You did.”

Dad cleared his throat. “She raised herself half the time,” he said. “I just kept the lights on.”

“Then you did more than most,” the Colonel said. Then to me: “I’m shaking your hand again before I leave or I’m going to lay awake tonight with the shakes. Don’t argue with an old man.”

“I wouldn’t dare,” I said.

Brett, who had spent ten years confusing confidence for competence, opened his mouth. “Sir, about the—”

“Brett,” Madison hissed. She didn’t stare daggers at him. She stared sharpened steak knives. He wilted, then forced a grin, then shut up as if his own teeth had told him what to do.

The Colonel stabbed a piece of ribeye, chewed, and smiled as if meat had never done him wrong. “Now,” he said, conversational as anything, “somebody tell me about this coworking whatever. Sounds like a thing my granddaughter would roped me into paying for if she were here.”

Madison lit up like a billboard in Times Square on New Year’s Eve. “Colonel, it’s visionary. We’re bringing creators and entrepreneurs together in one space—studio-grade lighting, sound booths, mentorship. The city’s grant could cover—”

“Mentorship,” he said, rolling the word around like a marble. “That’s where an older person tells a younger person not to do dumb things, yes?”

She laughed too loudly. “Exactly.”

“And the business model,” he said. “Where’s the money come from in month three when everyone’s done taking pictures of coffee?”

Madison blinked. “We…have runway.”

He nodded. “How much?”

Brett coughed. “Well, the—to be determined by—”

“Mmm,” the Colonel said agreeably. He cut his steak, ate, dabbed his mouth, looked at Dad’s hands again, and then at mine. “You ever think about running logistics outside the Army?” he asked me, casual as napkins. “I sit on the board of a veterans workforce program. We need someone who can build a schedule like a bridge.”

Madison inhaled so hard she swallowed half a sentence.

“I have a job I love,” I said. “But thank you.”

“Keep my number anyway,” he said. “Sometimes loving a thing and doing it there aren’t the same sentence forever.”

He turned to Madison and Brett, polite as the tooth fairy. “You two send me your pitch. We vet everything through the board. We like proof more than adjectives.”

They both smiled with all of their teeth and none of their eyes.

He lifted his glass. “To paperwork,” he said. “To the kind that saves your kid.”

Dad raised his. So did I. Even Mom, who prefers to keep her hands free for disapproval, reached for her wine and tapped it to mine.

Madison picked up her water and clinked, silent, and for the first time since we were teenagers I believed she did not know what to say.

Part 3

You’d think that would be the whole movie. Old soldier salutes the one nobody understood. Sister learns a lesson. Fade to credits.

The thing about families is they’re not a ninety-minute arc. They’re seasons. Sometimes you get a warm October. Sometimes it snows in April.

By dessert—pie that tried and failed to be Midwestern—Madison had slid back into performance mode like a woman reapplying lipstick after a hard cry. She told the Colonel about her “pilot cohort,” about the “creators” who were waiting to sign up, about “unlocking synergy.” He nodded and said “uh huh” and “go on” the way men who have watched prospects pitch for thirty years say uh huh when counting the ways they’ll say no later.

After we paid—Dad insisting on the check, Madison insisting on pretending she reached for her purse—the Colonel pulled out a pen and wrote his number on the back of a business card. He handed one to me, one to Dad, one to Mom because he’s old enough to know wives run households and sometimes men.

He did not hand one to Madison. She watched his hands, didn’t reach out, and then laughed too brightly and said, “We’ll email you, sir. We have the address.”

“You do,” he said. “Send the deck. You’ll get a fair shake.”

“Thank you,” she said, as if applause were owed to her for being tolerated.

He shook Dad’s hand, then mine again, holding a half second longer than men do with women when they are trying to be correct. “God bless you, Captain,” he said under his breath. “If you had been on my staff in ’91 I would have slept nights.”

“You still don’t,” I said.

He laughed, saluted without ceremony this time, and left.

Madison blew out a breath. “Well,” she said, “that was…unexpected.” She smiled, but it trembled. “Jordan, you should have told us you were…like that.”

“Like what?” I asked. “A person who did her job?”

“A person who gets saluted by—by that,” she said, vague with awe.

“You mean a person,” Dad said. He didn’t rescue her. He didn’t need to.

Brett scratched the back of his neck and put on his networking face. “Jordan,” he said, “what if we—like—collaborate? We could center veterans in the space. That would be huge for the pitch.”

“Center,” I repeated, flat, tasting the syllables like gristle.

“It would mean so much to Dad,” Madison said quickly, playing the oldest card she knows. “If we were all working together. Family.”

The waitress came with to-go bags we hadn’t asked for and too many mints. The lights over the bar flickered the way fluorescent does when it’s tired of lying about being reliable.

I stood. My napkin fell off my lap and slid to the floor. I didn’t pick it up.

“Madison,” I said. “Don’t use me like a prop. Don’t use the word ‘veteran’ like it’s a coupon code.”

Her mouth opened and closed. “I didn’t—Jordan, I would never—”

“You did,” I said. “Just now. You did.”

She put a hand out as if to touch me, then thought better of it. “It was a joke,” she said lamely. “Earlier. The copier thing. We were…bantering.”

“Banter that needs me to be smaller than I am,” I said, “isn’t banter. It’s cruelty with better lighting.”

Mom took a breath like she was preparing to referee, then released it. “Let’s not fight,” she said. “It’s a birthday.”

“It’s also a boundary,” I said, and Dad, God bless that man, put a hand on my shoulder like a gavel. He didn’t say anything. He didn’t need to.

We hugged in the parking lot the way people do in movies when the actors have only just met. Dad squeezed me twice and whispered, “I’m sorry I laughed,” and I said, “I’m sorry you felt you had to.” Mom kissed my cheek and smelled like powder and the kind of patience that often looks like denial. Madison hugged me with her arms and not her heart and then stepped back and said, “You’ll send the Colonel your resumé, right? Just in case?” and I said, “No,” because even if the Colonel had wanted me he would have asked without me having to climb over my sister to get there.

Brett held out his fist for me to bump. I looked at it until it felt like the world’s saddest meatball and then walked away.

That night, Dad called. He never calls after nine. “You awake?” he asked.

“I am,” I said, sitting up in the bed I built with money nobody gave me.

“Bobby texted me,” he said. “He said his son wants your email. Said there’s a…what do you call it? A thing at the base. A day when they bring in folks to talk. He wants you to talk. About Kabul. About…lists.”

“Tom,” Mom said in the background, scolding gently, “let her decide.”

“I am,” he said. “I’m letting her decide.”

I stared at the glow of the streetlight against the blinds. A moth threw itself at the glass and then gave up and rested. “I’ll go,” I said. “I’ll talk about printers.”

Dad laughed. The laugh I’d wanted at dinner.

Two weeks later, I stood at a podium in a gym that smelled like wax and history, and I told two hundred civilians and sixty service members how many ways paperwork can save a life. I made them laugh first. You have to do that, or they won’t let you get close. I told them about the bobby pin. I told them about the bus manifest with the name that was off by one letter and how we found the right letter because a private cried when she read it despite having been taught not to. I told them about a sergeant I never saw again who handed me a protein bar like communion because I didn’t have hands left to take it with.

Afterward, a young lieutenant came up with his wife and their baby, and his wife said, “Thank you for saying the boring part out loud.” I told her it wasn’t boring. She said, “I know. I just didn’t know how to tell my mother that.”

The Colonel shook my hand afterward and pressed a card into my palm with a phone number on the back I didn’t use, because you don’t spend favors like loose change.

Madison sent three texts that week. The Colonel’s office hasn’t written back yet. Do you think he got my deck? Do you think he liked it? And: Could you nudge him?

I replied: He told you where to send it.

She left me on read. The board sent a rejection two weeks after that with language so polite it would have held a door open and a sentence so clear even Brett couldn’t misinterpret it: We do not fund spaces; we fund programs with defined outcomes.

Madison didn’t speak to me for a month. Mom sent an email saying, “She’s upset. Be kind.” I printed it and put it on the fridge under a magnet shaped like Ohio and laughed every time I reached for the milk.

Part 4

Families don’t change the day you deliver a speech. They change on the days you help someone move a couch they shouldn’t have bought on a credit card. On the days you bring soup to a sister who has the flu and pretend you like her podcast. On the days you hand your father a photo album and say, “Tell me the story again.”

Madison went quieter. Not quiet. Quieter. She stopped tagging me in posts about “hustle” and started texting me photos of the twins covered in pizza sauce with captions like, “No idea how to get this out.” (“Cold water, then Dawn,” I’d reply. “Baking soda if you have to.”) She did not apologize. Some people are allergic to that word. She asked me to help edit an email to a potential landlord because it “sounded desperate.” I edited it. She got the apartment. She did not say thank you. I did not need her to.

Mom still told me to wear my uniform to church on Veterans Day even though I am not allowed. Dad bought a T-shirt at the PX that says ADMIN SAVES and wears it under his flannel like a man with a secret. It makes him happy. It makes me roll my eyes. It makes Mom sigh. Some things are eternal.

The Colonel sent me a photo at Christmas—him, his son, his son’s wife, a baby with hair like static. “All home,” he wrote. “Because of one good list.” I cried into my coffee and texted back a photo of my printer with a bow on it. He responded with a skull emoji and then “my wife says stop being cute and come to dinner when you visit D.C.”

Madison and Brett tried three more angles for funding. The city said no. The bank said no. A man at a networking breakfast said, “Interesting,” which is worse than “no” because it steals your time. They pivoted. They found a small space above a florist and launched a photography studio. They work hard. There are fewer adjectives in their speech now and more invoices. Every once in a while Madison texts me a screenshot of a glowing review. I reply with a thumbs-up and then “proud of you.” She usually replies with a heart. Sometimes she doesn’t reply at all.

The night everything tilted for good was quieter than a steakhouse. Mom made pot roast. Dad set the table. Madison arrived with a salad that tried to be fancy and a paper crane one of the twins had folded at school. We sat down.

“I have something to say,” Dad said, which is never the beginning of nothing.

Madison and I looked at each other. Mom frowned with love.

“I wasn’t good at being a father to a daughter in the Army,” he said. “I didn’t know how to talk about what you did because my war didn’t look like yours. I knew how to brag about a man with grease on his hands and sand in his teeth. I didn’t know how to brag about a woman with a black pen.” He took my hand. “I’m sorry I let anybody laugh.”

I squeezed his fingers. It wasn’t enough. It was everything.

Madison cleared her throat. “I have something to say, too,” she said, eyes on her plate, as if she needed the peas to give her permission. “I’m…I’m sorry.” She looked up at me. Her face was naked in the way you can only allow your face to be when you’re finally tired of pretending. “It was easier to make fun of what I didn’t understand than admit I didn’t get it. You’re better than me at a thing I’ll never be good at. I hate that. And it made me mean.” She swallowed. “I’m trying to be less mean.”

I didn’t stand up and clap. I didn’t cry. I passed the salt because this is how you accept what somebody who hurt you can give. Then I said, “Thank you,” because this is how you let them know they gave it.

Brett stabbed a carrot with unusual care. “Also,” he said, like a man stepping on a bridge he wasn’t sure would hold, “the copier jokes weren’t funny.”

Madison elbowed him under the table so hard he yelped. We all laughed because we needed the pressure valve opened before this became a Lifetime movie.

Two weeks later, Dad’s church did its annual Veterans Day thing. They lined men and women up by branch and made them wave at the congregation while people clapped and teenagers shifted in their pews as if gratitude itched.

“Is your sister coming?” Pastor Ellen whispered, handing me a paper program.

“She will,” I said.

Madison slid in beside me ten minutes later, hair pulled back, sweater ordinary, twins left at home because this wasn’t about them. The choir sang “America, the Beautiful” in a key my voice refuses. Pastor Ellen preached a sermon about service that made me a little angry and a little proud, which is how I like my sermons. Then she did the thing I knew she’d do: “Would Captain Jordan Hale come forward?”

I walked to the front. It felt like walking through mud and like walking in a field at night with the stars close. Pastor Ellen handed me a plaque because there is no American ritual that cannot be improved by a plaque. “For service rendered and for reminding us that the boring part saves lives,” she read, smiling. The congregation clapped. Dad stood up and shouted something he shouldn’t have. People laughed kindly.

In the back, a man in a suit—one of those real estate guys who always looks like he’s about to sell you a townhouse you can’t afford—put his hand to his forehead in a sloppy salute because America is complicated. I ignored him. I looked at my family. Mom cried. Dad wiped his eyes with his sleeve because he refuses to carry a handkerchief like his father did. Madison clapped. Not with her fingertips. With her hands.

Afterward, in the parking lot, Colonel Ellison’s son walked up. “You don’t know me,” he said, which is a lie I responded to with a smile. “But you saved me. You saved my wife. You saved my boy. I don’t have a way to say thank you that feels big enough.”

“Name him after me,” I said deadpan, and he blinked, horrified, and then I laughed and he laughed and we both needed it.

He grew serious. “There’s a lot of people who don’t make lists. I’m glad you did.”

We shook hands. The skin between thumb and finger is where truth lives. His was warm and steady. Mine was, too.

Madison hovered. “Will you—” she started, then stopped. “Never mind.”

“What?” I asked.

“Will you look over my pitch deck?” she said. “I’m submitting to a small grant for the studio. They want…outcomes.”

“Outcomes,” I said, tasting the word the way Dad tastes coffee to see if someone finally made it strong enough. “I can do outcomes.”

We sat at her kitchen table, the same one she once bragged had been “curated,” and I marked her slides up with a mechanic’s bluntness. Define “creator.” How many hours a month? How much revenue? Name the number of veterans you’ll train. Not “empower.” Train. She took notes. She changed language. She didn’t cry. I sent her back to rewrite a paragraph that made no sense. She did. She got the grant. It wasn’t much. It was enough.

She texted me a photo of the acceptance email with three exploding heart emojis and then, on a separate line, lower-case and unadorned: thank you.

Part 5

We were back at Cavanaugh’s a year to the day after the salute. Not because we planned it that way, but because Dad wanted the ribeye and the Colonel was in town again and Pastor Ellen had decided to try the salmon because the widow Hoffman swore by it.

Madison looked different. Not older. Not wiser. Just less…armored. She wore a plain black dress and flats that made no noise on the tile. Brett shook the Colonel’s hand and did not ask for money. He asked about the Colonel’s grandson and how long the Colonel had stayed married, and the answer made him whistle low and say, “Teach me.”

We finished the bread before the jokes, which was a nice change.

The hostess led a man through the door midway through the meal—a new guy on the city council who wanted to be seen wanting to be seen. He took three steps into the dining room and stopped when he saw the Colonel.

“Sir,” he said, bobbing his head, offensive line meets high school principal. “Big fan.”

“Of what, son?” the Colonel asked. “Me? Or your idea of me?”

The councilman laughed like that was a joke and asked for a selfie. The Colonel obliged because it cost nothing and would bug the right people. He came back to the table rolling his eyes in a way only men old enough to not care anymore can.

“Still gets me,” he said to Dad, tipping his water glass toward me. “The good ones never wave their medals around. It’s always the men who tripped down the stairs.”

“Maybe someone tripped down the stairs because somebody didn’t fix the lightbulb,” I said. “Somebody ought to look into that.”

Madison grinned. “Outcomes,” she murmured, teasing me now, yes, but with love.

The Colonel’s phone buzzed. He glanced at it, then frowned, then grinned. “Speak of the angel,” he said. “It’s my boy. He’s at the grocery store with the baby. He says to tell you the kid likes to tear napkins and he keeps handing him back the same napkin and the child looks betrayed. Parenting is war,” he said cheerfully. “Different supply chain.”

We laughed. Dad laughed hardest. The waitress refilled coffee without being asked. The busboy adjusted knives with reverence reserved for dinnerware in restaurants that serve guilt with the cheesecake.

“Jordan,” the Colonel said, suddenly serious in a way that made us all sit up straighter. “I want you to know—I know you didn’t need a salute that night. I know you didn’t do the thing you did for a room full of people to stand and clap so they could feel right about a country that often gets it wrong. But I needed to. I needed to because old men like me spend our mornings with ghosts and our afternoons convincing our wives we’re not sad when we are, a little. And sometimes a thing worth doing deserves a ritual so we can bear it.” He took a breath. “Thank you for letting me bear it with you.”

I could have made a joke. It’s my reflex when things get naked. Instead I reached across the table and put my hand on the back of his. “Thank you for making the room quiet,” I said. “I didn’t know how much I needed quiet until you gave it.”

Madison looked at me and didn’t look away. “I’m proud of you,” she said, simple, the way she should have said it years ago when I graduated OCS and wore a uniform that fit for the first time.

“Me too,” Dad said. “Always,” Mom added, a correction she needed us to hear. I let her have it. Grief is a kind of math, too. You subtract a thousand small insults and add one good sentence and call it even for the night.

When the check came, Madison grabbed it. “Don’t argue,” she said, anticipating the Colonel. “Outcomes.”

He squinted at her, laughed, and let her pay. “What are you, rich now?” he asked.

“No,” she said. “Just grateful.”

We walked out into the kind of Ohio night that makes you think moving might not be necessary after all. The Colonel hugged Dad the way men who almost died together hug—arms hard, hands flat, brief and infinite. He turned to me, saluted again—small, just between us this time—and then squeezed my shoulder hard enough to leave a bruise no one would see.

Madison stood by my car, keys swinging from her finger like punctuation. “Photocopier Captain,” she said, and for a second my stomach dropped to the place it had the year before.

Then she smiled. “You know I’m never living that down, right? The joke on me. Forever.”

“Forever’s a long time,” I said. “We can settle for a while.”

She nodded. “For a while.” She looked at me. “Thank you. For not making me pay for the whole bill I ran up.”

“I’ve got freezer space,” I said. “You can pay me back in leftovers.”

She laughed. It made a better sound than last year. Fewer knives.

Dad climbed into the passenger seat, humming something that couldn’t decide if it wanted to be a hymn or Merle Haggard. Mom fussed with her shawl and then stopped and held it closed with her own hands. Brett opened the car door for Madison and said, “After you, boss,” and she rolled her eyes and kissed his cheek anyway.

I watched the Colonel drive away until his taillights blurred. I stood for a minute and breathed the cold and the steak grease and the perfume of my mother’s generation. I thought about lists and buses and bobby pins and the law of gravity in rooms where laughter can drop like a stone on your head. I thought about the way a salute can change the oxygen in a room, and the way my father’s hand had felt on my shoulder like a benediction he’d been practicing since a hospital room in 1989 when he had no idea how to hold a daughter and did it anyway.

Families don’t turn into poems. They’re more like ledgers. You write in black ink and red and hope the month ends in the black. You cut the jokes that cost too much and keep the ones that don’t ask you to mortgage your dignity. You build a balance sheet out of small mercies, big dinners, coffee in old mugs, and the occasional steakhouse miracle.

On the drive home, Madison texted me a photo. It was the twins, asleep on the couch in a pile like puppies. The caption said, “Someday I’ll teach them to fix a printer.”

I replied with a photo of my bobby pins, a little bent, a little proud. “Start here,” I wrote.

At a red light, I laughed. Not because anything was funny. Because the room was quiet and the air felt right and the road in front of me was mine to drive, and because somewhere an old soldier was telling his grandson about a woman with grease on her face who made a list good enough to bring him home.

That night, when I turned off the lamp, I saw it again: the slice of a palm, the debt an old man needed to pay, the silence that followed and made everything clear.

Photocopier Captain.

Fine. If the copier keeps the names legible, the list true, the bus on time, and the kid alive?

Captain will do.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood

HOA Demolished My Lake Mansion for “Failing to Pay HOA Fees” — Too Bad I Own The Entire Neighborhood …

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her

They Mocked Her at the Gun Store — Then the Commander Burst In and Saluted Her Part I —…

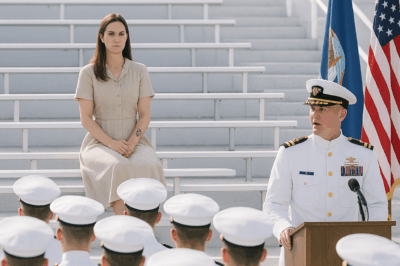

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze

She Only Came to Watch Her Son Graduate Until Navy SEAL Commander Saw Her Tattoo and Froze Part 1…

“What’s that patch even for ” then the colonel said,“Only five officers have earned that in 20 years

“What’s that patch even for” then the colonel said, “Only five officers have earned that in 20 years” Part…

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence – That Was Their Biggest Mistake

Family Demanded To ‘Speak To The Owner’ About My Presence — That Was Their Biggest Mistake Part I —…

My husband & I didn’t finish high school & our son’s wife who graduated from an Ivy looks down on us

My husband & I didn’t finish high school & our son’s wife who graduated from an Ivy looks down on…

End of content

No more pages to load