My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were…

Part One

The first photograph slid across the mahogany like a blade. Then another. And another.

I sat very still as Amanda aligned each glossy rectangle so the entire Bennett clan—and the two guests my mother-in-law had insisted were “practically family”—could admire the tableau she’d so painstakingly assembled. There I was in each shot: head inclined, hands moving, laughing in that open-mouthed way you only laugh when you’re thinking about something more important than your own face. Beside me: a rotation of men in tailored jackets, their profiles captured mid-sentence, mid-gesture, mid-whatever Amanda planned to call it when she detonated my life on a Wednesday.

She cleared her throat—performance beginning—and placed an elegant palm on my husband’s shoulder. It was the kind of touch a casting director would call “possessive maternal,” but Amanda was only my sister-in-law. She squeezed, as if warning him to hold still. “David,” she said, ladling concern like gravy, “I wish I didn’t have to be the one to do this. But you deserve the truth.”

David stared at his water glass the way people examine a riddle they already know the answer to. He didn’t meet my eyes. I watched the pulse beat at his temple and thought of all the times I had wanted him to be brave.

My mother-in-law Eleanor’s fingers trembled over the nearest photograph. She inhaled sharply. “Sophie,” she breathed, tilting the picture like a relic. “How could you?”

Across the table, Jessica—yes, the Jessica who had stolen my husband in all but paperwork—inhaled in solidarity with Eleanor and then looked down politely. George, my father-in-law, shifted in his chair like a man wishing he’d developed a sudden affection for fresh air.

While they posed, I placed my hands in my lap and pressed my thumbnails into the soft meat of my palm until I felt the pain shoot clean up my wrists. Pain is so useful when the room wants to drag you under. It says stay. It says observe. It says this is the part where you memorize how they look while they believe they are winning.

“What do you have to say for yourself?” Amanda prompted, already turning to present my reaction to the spectators. The dining room glittered with chilled crystal and curated disapproval. I counted twenty-three faces if I included the oil portrait of George’s father—the founding Bennett, forever watching over roast beef and succession plans.

“Nice photos,” I said lightly. “Excellent light. You must have paid your private investigator very well.”

Her smile faltered. Not the script. It took exactly one heartbeat for her to recover. “So you’re not even going to deny it?”

“Why would I?” I asked, sliding my tablet from my bag and laying it on the linen, its matte screen reflecting their faces like a low dark lake. “Those men are all divorce lawyers.”

Silence. That heavy, theatrical silence people in expensive clothing are sure will force you to fill it with something shameful.

I gestured, pleasant as a hostess with a cheese board. “That’s James Morrison. He eats in the same booth at Le Soleil every Thursday and wins ninety-two percent of his cases. Michael Turner joined him the following week—he specializes in fiduciary shenanigans, which I thought might be relevant. And this one here is William Parker, particularly gifted at untangling assets that try to hide under shell companies with names like ‘HarborView Capital’ and ‘Pinegrove Holdings.’”

Across the table, George went a shade paler. If guilt had a Pantone, it would be that faint green that crept up his cheeks.

I clicked the tablet awake. Emails with signatures marched across the screen. Engagement letters. Calendars. Retainer confirmations. I swiped and their neat fonts glowed benignly.

Amanda sank into a chair with the flummoxed grace of a swan forgetting it had legs. “You knew,” she whispered. “You knew this whole time.”

“I learned three months ago,” I said, finally lifting my eyes to David. “A lipstick on a shirt. A slip like a movie cliché. A text message that read ‘next time no mint chocolate chip’—you’ve always hated mint. And then I learned more. Because I listen, and because I don’t confuse the warmth of a marriage bed with a seatbelt.”

David looked sick. He opened his mouth and closed it. On a better day, in a different marriage, I would have rescued him. That day, I took a sip of water.

Eleanor, shaking, tried to fit us all back into the roles she understood. “Sweetheart,” she said to David, the endearment wobbling, “we will get you through this. We will find the right lawyer—”

“You already did.” I leaned back and folded my hands. “Only I found them first.”

The guest on Eleanor’s left—the one she’d been auditioning as a post-Bennett confidante for months—shifted in her chair and tried not to look fascinated. Across from her, Jessica flinched and then folded her napkin with the precision of a person who knows she is not the only lightning rod at the table.

“I don’t know what you think you’ve discovered,” George attempted, upping the bass on his voice, lowering his chin in that patriarchal angle men think will make their words heavier. “Routine family business isn’t fraud just because you don’t understand it.”

“I understand enough,” I said. “I understand that the transfer of three rental properties into a new LLC occurred two days after David moved his suitcase into the guest room. That your ‘routine’ removed my name from the family business’s key asset list without notification, and that the trust amended at that same meeting attempted to reroute distributions away from spouses in the event of divorce.”

In another life, I would have softened what came next. In this one, I let the truth clink down like cut crystal.

“And I understand,” I added, tapping the tablet until a voice memo icon winked into existence, “that the two of you”—I flicked my eyes between David and Amanda—“met privately at Caffè Roma and recorded yourselves brainstorming how to ‘make the gold digger walk away with nothing.’”

Amanda shoved back from the table so fast her chair scraped the oak. “You recorded us?”

“I didn’t,” I said. “Jessica did. The day she realized men who cheat with you will also cheat on you.”

Jessica’s cheeks flared. She stared at her plate. For the first time since this began, I saw a person under the gloss.

The room erupted. Eleanor dissolved into tears with the reflex of a woman who has never had to wonder if crying will help. George sputtered legal nonsense. David’s lawyer—because yes, he’d brought one to dinner and thought no one noticed—began murmuring about “civil paths forward.” Amanda accused me of “orchestrating a humiliation.”

“You did that part yourself,” I told her gently.

James Morrison—who had agreed to attend if things went off-script—stood from the corner he’d claimed near the sideboard and cleared his throat. He’d eaten three canapés and exactly one olive. “We can continue shouting,” he said, “or we can sit down tomorrow at ten and sign away your risk of criminal exposure. Mrs. Bennett has prepared a settlement that is—if I may use a word I rarely apply in these circumstances—merciful.”

David’s head whipped toward me, the boyish tilt he used to deploy on me when he wanted forgiveness resurfacing like a bad habit. “When did you get so…calculating?”

“Somewhere between your gym selfies and the first time you lied about a late meeting,” I said.

I collected my bag. My shoes sounded obscenely loud on the floorboards as I left. On the way out, by the foyer mirror where Eleanor insists fresh flowers live even in January, I allowed myself a single look at a woman I recognized and liked: the set of her mouth, the steadiness in her jaw. I smiled at her. She smiled back.

James’s office the next morning smelled like leather and mum. The Jacobsen lamp on the credenza looked like it had always lived there. Papers spread across the table like runway models—sleek, expensive, designed to be seen. I had already signed my pages. All that remained was for the Bennetts to decide who they wanted to be when they left the room.

David’s lawyer tried to stage a theater of indignation. James interrupted with the elegance of a maître d’ closing a door on a drunk. He laid out our timeline, our evidence, the statutes, the consequences, the choice.

“You can fight,” he said conversationally, “and risk charges for fraudulent conveyances. Or you can accept a division that reflects Mrs. Bennett’s considerable contributions to both family and business, unwinds your bad faith transfers, and ends this privately. We prefer the latter. So would your board. And so would Mrs. Bennett’s private investigator, who was—how shall I put this—willing to offer both loyalty and volume discounts.”

“We hired you,” Amanda snapped, finally finding a place to aim her fury.

James raised a gentlemanly palm. “You hired a different firm. They subcontracted. Our industry is small, Ms. Bennett. We share vendors. You will find ruthlessness in textbooks and in movies. In real life, it looks like a collection of very polite men who know how to do math.”

George went gray. Eleanor dabbed like the corner of her eye was a wine stain. David stared at the pen James slid toward him like it might bite.

He signed. Then George signed as trustee. Then—oh, the opera in this—Amanda signed as the newly removed “advisor.” A neat slash of ink that undid months of scheming and years of entitlement in one stroke.

As we stood to leave, David found his words again. “Sophie,” he said, and I remembered how stupidly in love I had been with the way my name sounded in his mouth before I learned he could say it to two people in one day.

I did not turn. “David,” I said, in the tone I save for dogs bolting toward open doors. He froze. Good boy.

Outside, the city had put on that crisp shade of afternoon that makes even ordinary streets look like they might lead to something cinematic. A woman passed with a white dog in a tiny sweater. Two teenagers laughed too loud. A delivery guy balanced fourteen boxes of something on his thigh and grinned at me when I held the door. On impulse, I texted Jessica. It’s done.

She wrote back one line: Thank you. And then, slower: I’m sorry.

I stood there on the sidewalk with the phone warm in my hand and felt the strangest thing: not triumph, not vindication—though both would have been understandable. What I felt was something like grief for a version of my life I had defended with both hands long after it deserved a defense. Inside the grief, a clean new room I could walk into without apology.

That night, I opened a folder I had been building in my head for years and built it on paper: a consulting practice for women who had started believing they were somebody’s afterthought. It would be part strategy, part logistics, part old-school hand-holding, part new-school forensic wizardry. I called it Glasshouse, because I thought I should and because there is no better feeling than deciding you won’t live in one

anymore.

Part Two

Six months later, the photographs Amanda had thrown like daggers had curled up under magnets on my fridge. I used them in workshops to teach the first rule of survival: control what your enemy thinks they see. “They’ll call this manipulation,” I told a conference room full of women in polite blazers. “I call it design.”

Glasshouse lived in a loft with tall windows and honest floors. The day we opened, a florist who had heard the gist of my story sent us buckets of sunflowers. “They’re bossy,” my associate Kendall said, arranging them in vases. “They look in one direction and expect you to follow.”

“Good,” I said. “We need the energy.”

Our first clients arrived carrying folders full of nonsense and faces full of fear. I sat with one woman while she cried about the twenty-two years she had spent believing the way her husband sighed was her fault. We taught her how to scan every bank statement, how to read the numbers out loud until they told a story she could make choices from. Another woman brought price tags as evidence: peaches, pearls, pain. We told her she didn’t have to explain her desire to keep the Le Creuset. “It’s not about the Dutch oven,” Kendall whispered to me later. “It’s about having one heavy thing that feels like it will outlast the known world.”

Jessica came once a week to help sort spreadsheets and, slowly, the story we never found time for when our lives were interlaced with the Bennetts unspooled on lunch breaks and after-work walks.

“He told me,” she said one afternoon, staring down into a bowl of pho like it might offer absolution, “that I was different. Because I listened.”

I smiled into my spoon. “He told me that, too.”

We built our friendship on that kind of gentle accounting—what did we believe and why. Between confessions, we wrote ten protective clauses for women we pretend are protected by vows. We pitched companies on paid leave for family court days. We built a small scholarship for legal fees. We discovered that four hundred dollars given at the right moment can change a life in six measurable ways. We sent Amanda a brochure on financial literacy for executives with a handwritten note: No sarcasm intended.

“Do you think she opened it?” Kendall asked, arching one eyebrow, the way she does when she knows I will choose mercy over curiosity.

“No idea,” I said. “Not my homework.”

Rumors of the Bennetts’ implosion did what rumors do—grew horns and wings and a sense of righteousness. People asked me at networking breakfasts if it was true I’d “put George in his place.” I told them I reminded him he had one. People wanted gory details. I gave them the only ones that matter: dates, signatures, the way a law written on a page can lift a woman’s chin.

As for David, I tried not to know things. Information has a gravity I’ve learned to respect. Still, some news is the kind that tips under doors: demoted quietly (“restructured”), an apartment leased in a different neighborhood (“fresh start”), a global tour of self-help podcasts posted late at night. A photograph of him at a 5k raising money for heart health, his hand on a woman’s shoulder, both of them smiling too hard. I felt nothing and then—because I am not a monster—wished him a life of ordinary decency with someone who can smell honesty the way I smell rain.

Amanda took a junior role at a firm without a receptionist. Eleanor leaned harder into charity luncheons and less into monologues. George retired to a quieter golf course, his name slowly sliding off letterhead like a sticker you forgot to press down on the corners. The family portrait in their dining room acquired a thin patina of dust before someone finally moved it to the hallway. I did not go to see. Jessica told me about it in a text punctuated with a line of laughing-crying emojis and then she added: It’s weird how heartbreaking it is to see the old world fade. I typed back: It’s also how new ones get the light.

One afternoon in late spring, Glasshouse hosted a seminar we branded “Post-War Peace.” Thirty women sat in a ring and wrote down the one sentence the man in their story had used to control the room. Don’t embarrass me. We’ll talk about this later. You’re not being rational. They read them out loud and then pressed match-tips to the paper and watched them blacken in a pyrex bowl. When it was Jessica’s turn, she paused and then wrote something different: I forgive myself. She didn’t burn it. She folded it into her pocket.

By summer, we were profitable. We sent three women to law school and six to bookkeeping courses because revenge that ends with a verdict is interesting, and revenge that ends with a life you can budget is freedom. We hired a paralegal who could sense when someone needed a tissue thirty seconds before they knew it. We kept a bowl full of sour gummies at the front desk and labeled it “courage.”

On a Tuesday in September, Amanda showed up in our lobby, smaller than I remembered and with the brittle cheer of someone who has learned how to make a face that stays on. She held a bakery box out like an apology. “Almond croissants,” she said. “From that place you liked on 6th.”

I could have sent Kendall or our receptionist. I went myself.

“I wanted…” she began, and then her voice—that voice that had carried my guilt through houses I cleaned for free—cracked. She tried again. “I wanted to see where you work.”

“This is Glasshouse,” I said, holding the door wider. “We help women not break.”

A muscle jumped in her jaw. She scanned the room as if taking inventory of a planet she feared would not recognize her passport. “Is there a—” she gestured vaguely—“a place where I could…learn what I don’t know?”

“We have a Tuesday night class,” I said. “It’s loud. There’s homework.”

She nodded, lips pressed tight. “I’ll come.”

I waited for the quip. It didn’t come. She meant it. I stood there with the bakery box between us like a peace lily and wondered what it must feel like to decide to be different after you have made being this way your job. I hope I never have to know. I hope I always do. Both can be true.

On the first night of class, she sat in the back with a pen and wrote down everything. When the lights flicked on at the end, she waited until the room emptied and asked if we could talk. We sat on the steps outside while buses punctured the quiet and she told me all the sentences she would never say out loud again.

“I thought,” she said, “that guarding the gate was love.” She laughed once without joy. “But it was just…guarding the gate.”

“There are better gates,” I said.

“There are better gardens,” she replied.

And then she left, with a workbook under her arm and a Tuesday circled in her phone.

In October, Glasshouse partnered with a community college to create a micro-credential in financial self-defense. On the second night of the pilot class, we needed a story about “The Asset Nobody Thought Mattered.” I showed them the photographs Amanda had thrown at me. I told them about the way you can turn your enemy’s eyes into your camera. I told them about hiring a private investigator who was a human being with a mortgage. I told them about truth as a tool instead of a threat.

A woman in the front row raised her hand. “What if you don’t have the money for James Morrison? What if all you have is you?”

“Then you start with a notebook,” I said. “You write down dates. You ask for copies. You don’t apologize for wanting to understand your own life. You fight cheap. You fight clever. You fight long enough to find someone who has fought before and will lend you a map.”

In November, Eleanor mailed a letter in her looping hand. It was addressed to me, not “Mrs. David Bennett,” and it did not apologize because apologies written by committee never sound like forgiveness. It said: George is planting tomatoes when it is too cold. We are learning that you can soak beans overnight and they taste good. I tried to make a budget and cried about how many times I wanted to write “party favors.” Do you remember the blue coat you wore to Thanksgiving three years ago? I see it in photographs and feel silly for how jealous I was of your ease. I think I am saying I’m sorry. I am certainly saying I love you. Love, E.

I saved it. Later, when winter hurt my windows and I needed a reminder that people can sometimes surprise you, I took it out and smoothed it flat.

On a gray Thursday before Christmas, I received a postcard from the judge who’d presided over my settlement. It had a drawing of a lighthouse on the front and on the back it read: You were the calmest person at a table I have seen in twenty years. Calm wins more wars than fury does. I taped it to the inside of my files cabinet where only I could see.

December came, as it always does, wearing lights that make ordinary streets look like promises. Jessica and I drank cocoa spiked with something that made us sentimental and talked about new kinds of traditions. “We could do found-family dinner,” she said, eyes bright. “All the people who carried us when the blood family looked away.”

“Catered?” I asked, deadpan.

“Potluck,” she said, like a person rediscovering a word she used to love.

We held it at the Glasshouse loft. The women from our Tuesday classes brought casseroles and stories. There was more laughing than crying, more hugging than scheming. Amanda came late, breathless, bearing a tray of almond croissants and a face that said I know where I failed and I am not asking for absolution. She sat in a folding chair near the door, and when it was her turn to say one sentence she would teach her younger self, she said, “Your fear is not their responsibility.” We applauded the way women clap when another woman doesn’t explode into glitter under the weight of the thing she just put down.

The next morning—Christmas Eve—I woke up, put on a sweater that made me feel like a good decision, and drove to a building with my name on the deed and my fingerprints all over the blueprint: a set of transitional apartments we’d finished in September. The lobby smelled like paint and pine. Someone had put a paper snowman on the bulletin board and drawn a family around it with crayons.

Kendall met me at the elevator with a clipboard and a grin. “Ready to play Santa?”

We knocked on doors and handed out envelopes. Fifty dollars for the mom whose ex always scheduled his payments for after the twenty-fifth. A grocery card for the student with two part-time jobs who wanted to bring pie to her aunt’s house. A phone number for a pro bono therapist. A reminder that court clerks have neighbors and are less scary if you admit you’re scared. We told them truthfully that the best revenge we had ever tasted was watching a woman believe she could make a life happen and then watching her do it.

In the afternoon, I drove out to a small house where the Bennetts had eaten the same meal on the same plates since 1987. I stood on the sidewalk for three long breaths with an almond croissant in my pocket like a talisman and thought about turning around. Then I rang the bell.

Eleanor opened the door and stepped onto the porch with me. There was ham in the air and humility on her face. We did that awkward dance families do when some things are forgiven and some are merely acknowledged. We stood within arm’s length and did not kiss each other’s cheeks. We each said an easy sentence about the weather as if the weather had been the problem all along. We took a matching amount of responsibility for pretending that for years in a row.

Then she reached into her sweater pocket and pressed something into my hand. “Open it later,” she said, half-teasing. “It will be more sentimental if you do it alone.”

I laughed and promised, and then she surprised me and said, “Or open it right here.”

I did. Inside there was a photograph—one of the glossy ones Amanda had hurled like evidence. In this copy, someone had written on the margin in Eleanor’s careful script: May we take our seats before we judge the menu next time.

Behind her, I saw in the hallway mirror a reflection that made me want to laugh and cry at once: a woman who had been underestimated long enough to have built a city while everyone else was miscounting her forks.

George appeared in the doorway, sheepish like the town mayor after a flood. He shifted his weight. He looked at me the way a man looks at a subject he knows will never again accept a speech. “You’ll think this is silly,” he said, scratching his temple, “but the tomatoes turned out.”

“I don’t think it’s silly,” I said. “I think it’s honest.”

“That’s new for us,” he admitted, and then the porch light came on, and we both squinted into it like people at the edge of a stage they used to run without ever admitting how much they liked the audience.

I left after one cookie and two minutes of polite chitchat, because forgiveness that isn’t forced tastes better, and because I had a dinner date with people who knew how to pass the salt without passing judgment.

That night at Glasshouse, women we had fought beside and fought for and sometimes fought circled a table covered in food that didn’t impress anyone but delighted everyone. Someone’s kid drooled mashed potatoes onto a sequined table runner and no one reached for a napkin quickly. We used our fingers. We made messy plates. We toasted nothing and everything. We told small truths and a few big ones and kept two of the worst ones in our pockets for later when kitchens are good at holding late-night confessions.

On my way home, I drove past the Bennetts’ house and saw through the window the silhouette of a family that had finally been asked to look at itself in a mirror. I wished them the courage to do it without flinching. I wished myself the grace to keep moving whether they did or did not.

Back in my apartment, I set the photograph from Eleanor on my mantle. Beside it, I placed one of my own: a candid someone had snapped at Glasshouse earlier, all of us laughing too hard, a blur of hands and hope. Between them, I tucked a small card with a sentence that had carried me out of the dining room and into this new life: Never underestimate a woman who has proof and a plan.

Then I turned out the lights, climbed into a bed I chose, and fell asleep like people do when the rooms of their life match the furniture of their character.

END!

News

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My ‘Affairs’ At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… CH2

My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My “Affairs” At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed… Part One The first…

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything. h2

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything Part One…

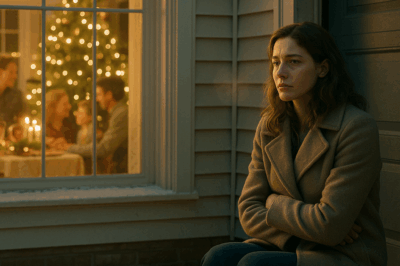

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own… ch2

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own the House…

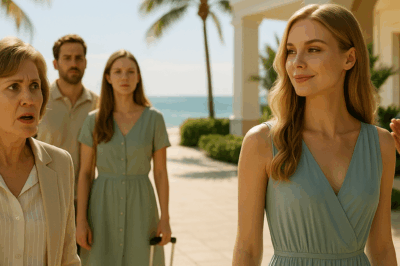

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… ch2

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load