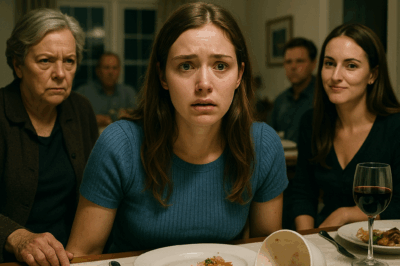

My Sister Got Me Fired, Then My Family Demanded Money When I Found Success. What They Got Instead…

Part One

The message on my phone felt like a physical shove. Miss Hall, please come to my office immediately. For someone who prided herself on being the steady, reliable person people could count on, being summoned felt like a small blaring alarm: something had gone wrong.

My name is Isa Hall, and for five years I had been a senior account manager at Morgan & Pierce. I’d taken calls at midnight, smoothed client meltdowns, and babysat impossible timelines until everything landed gently where it was supposed to. I showed up early, kept promises, and let other people—my family—be dramatic on their own time. I had a master’s degree in business administration and a carefully built reputation. I never expected my sister to weaponize “concern” and hand me an envelope of lies.

Fernando’s office smelled faintly of the expensive cologne he favored and of coffee gone cold. He looked at me with that expression managers wear when they’re about to say something impossible. “Sit down, Isa.”

He slid a printout across the desk. My name was bolded in the header of the email. “This morning we received a call,” he said, “from a woman who identified herself as your sister. She alleged you have a substance abuse problem, that you attend client meetings intoxicated, and that you steal company property. Given the severity of those claims, and the potential liability with certain clients, the board has decided to terminate your employment effective immediately.”

I remember the way the letters on that document blurred for a second. I remember asking for a minute, for an explanation, for any proof beyond a voice on the phone. The office security was there within an hour, a polite escort to the HR desk to retrieve my personal things. My colleagues’ faces were blank with curiosity and a sliver of sympathy, as if they were watching an elaborate scene from someone else’s life.

I called Victoria the moment I could. She answered, sing-songed and breezy. “Sis! What’s up? Did you finally spice up your life?” When I told her I had been fired, she laughed.

“A prank, Isa. You are so serious all the time. Lighten up.”

There’s a peculiar kind of betrayal in that laughter. The people who are allowed to joke at your expense are people who think you’ll always be there to pick up after them. My parents were cut from the same cloth. My mother called me within twenty minutes of the dismissal, not with concern but with annoyance. “You have to learn to take a joke,” she said. “Maybe this is the universe telling you to try something new. Victoria’s friend needs help at a boutique—wouldn’t it be nice to work together?”

They had been playing roles for my entire life. Victoria in the center, radiant as the family sun; me on the edge, quietly keeping things from wobbling. Taking care of the ledger, sending the invoices, making sure the family story looked good enough to be posted. That day, it all came undone.

It could have been a moment for me to fall apart. For a beat, I let shock numb me. Then anger—hot and bright—arrived, and with it a kind of clarity I hadn’t had in years. I thought of every time they’d enabled Victoria: the college applications they’d spun into a narrative of “we work with the arts,” the bailouts for Quinn’s bad business bets, the excuses pasted over one selfish moment after another. I thought of my own steadiness and of how it had been used as a cushion for their recklessness.

Instead of licking wounds, I started to write applications. Where one door slammed, I would build another. I updated my resume, connected with contacts on LinkedIn, emailed headhunters, and quietly put myself forward for positions I’d once thought unreachable. The first interview that bit was with Stuart & Associates—a mid-sized firm with a reputation for poaching clients by making smarter pitches and being ruthlessly organized. I met Larry Ford two weeks after the firing. He had a larger office and an even larger smile.

“Why us?” he asked, pen poised.

“Because I want to prove something,” I said. “Because I don’t want to let a malicious prank define me.”

He liked the way I laid out the numbers for Riverside Corp., how I could speak fluently about client margins and retention strategies. Two days later I had the offer. The salary was double what I had been earning, the bonus structure real and attainable. Walking out of Stuart & Associates, I felt a lightness that surprised me. Victoria must have expected me to stay down; instead, I was stepping up.

That should have been the end of it. But family has the tendency to see success as a resource rather than as an achievement. My new job announcement spread through our family group chat like wildfire. I watched our dynamic unfold in little digital ways: my mother’s immediate comments about how proud she was, then an immediate pivot to whether my success could cover Quinn’s car payment; Victoria’s sly inquiries about spots I could “help” her with at her art supply store; my father’s casual suggestion that my bonus could be used for “kitchen renovations.”

The requests were never direct at first. They were gentle nudges disguised as familial concern. “You must feel so accomplished—treat us,” my mother wrote. “Your sister needs a small loan until her commissions come in,” Victoria texted privately. Quinn, as always, was blunt about his needs: the bank has called; can you cover $3,000? You’re my only hope.

I watched all the messages stack up and felt something shift under my feet. In one corner of my apartment I had a neat stack of receipts, invoices, and a small notebook where I’d been jotting family incidents for years—dates of loans no one repaid, the nights I’d covered Victoria’s car inspection when she’d forgotten, the times Quinn had blamed me for things I hadn’t done. Those notes were scribbled as notes to self, not as weapons. But as I read through old texts and bank transfers I realized they were a map of favoritism and enablement. I could either continue to be the family ATM, or I could stop being complicit.

I did something practical and quiet: I began collecting evidence. I set up a folder and forwarded bank statements, screenshots of texts begging for bailouts, photos of purchases blamed on “maintenance,” and email threads where my mother requested I “handle” things so they wouldn’t worry. I documented everything not because I wanted to humiliate them, but because I’d learned long ago that people will gaslight until you have proof.

I wrote letters. Not angry, not vengeful—clean, crisp letters. Each addressed to a family member, each containing dates, amounts, and the pattern of requests that ended with an assumption of entitlement. For Victoria: the record of purchases labeled as art supplies that mapped to designer handbags. For Quinn: bank statements showing recurring cash withdrawals near the racetrack. For my parents: credit card statements showing luxury subscriptions and a second mortgage no one had mentioned at Thanksgiving. I attached receipts, account numbers, and a short note explaining that the financial enabling would end.

You might think that’s an extreme reaction. Maybe it was. But I’d been enabling for years in more invisible ways. And every time I’d said no, they’d played the same old roles: victim, martyr, offended. The letters were a clean way to force a conversation they had never been willing to have.

I mailed them as certified letters so I’d know the moment they were delivered. Then I went to work.

My first week at Stuart & Associates felt surreal. Larry was right—my knowledge of Riverside Corp. became not just a personal feather in my cap but an organizational advantage. The old firm, Morgan & Pierce, hated the idea of losing their account. I made no effort to rub it in. That wasn’t my point. My point was that I was capable of building something for myself that didn’t revolve around being everyone’s soft place to land. I was good at my job. I helped the firm win theirs. And yes, that put more money into the bank account.

The letters arrived like timed charges. My mother opened her envelope first. I imagined her at the kitchen table with a glass of wine, peeking at the notes, then feeling the familiar impositions rise like steam. My father got his; Victoria’s arrived and I pictured a dramatic gasp and then furious typing. Quinn’s was the one I worried about least. He was ashamed, and that hurt more than anything. But it also gave me the tiniest hope that he might change.

By the time the letters had been delivered and acknowledged, the family chat went from casual banter to a slow burn. My mother called me in the lobby of my office building. She was angry, as if I’d committed a deliberate social crime. “How dare you have the nerve,” she whispered further from shame than fury.

“Everything in that letter is true, Mom,” I said.

The confrontation didn’t play out like a scene from a movie. It was small, sharp, and entirely real: my mother standing there, clutching the paper, and me telling her that I had limits. She left after security was called. People at work watched the whole exchange with thinly veiled interest. But I had done the practical, boring thing: I had documented and I had acted.

Being fired had been the jolt I needed. The prank had been ugly and callous. But it had also removed a comfortable role I’d always performed for them. I no longer wanted to be the person who paid for everyone’s inertia. I wanted to build and protect my life.

When the trust shakes, everyone notices. Morgan & Pierce did not immediately implode over the loss of an account, but the board had to answer hard questions about how quickly they believed a voice on the phone. The firm that had fired me ended up—ironically—being the first organization to realize their error. I won a place at a table that respected me for my work, not for my patience. That mattered.

And still, within the first week of my new role, the guilt trips started again. “Family helps family,” my mother said when she asked me to pay for the kitchen deposit. The old refrain—soft and laced with obligation—arrived like clockwork.

Only this time I’d mailed the letters. Only this time I had documented everything and delivered it precisely where it needed to be: in my family’s hands.

At the end of a long second week, when the certified-tracking app showed three of the four envelopes delivered and signed, I sat at my desk and breathed. The rest of that afternoon unfolded like an odd mix of legal procedural and family drama. The companies I worked with began to respect the distance I was creating; my colleagues celebrated the promotion the board had quietly approved. Life, in an odd way, began to re-center.

There was one more piece to arrange: the board at Stuart & Associates wanted to reward impact and leadership. A few weeks after my promotion to senior partner was suggested, I began to get the impression that Morgan & Pierce’s loss was their gain. Larry told me one night, “They asked repeatedly why they fired you. When we took Riverside, the answer became obvious.”

I smiled, but my smile was not for revenge. It was for proof that doing the right thing—being competent, accountable, committed— outlasts pranks and small cruelties. The family, in contrast, wanted immediate currency. They wanted checks wired the minute I had them. They wanted to be included in my success as if it entitled them to share in the spoils.

So I mailed the letters. I did the boring, adult thing—document, deliver, and then I continued building. I promised myself I would not be baited. I would be pragmatic. I would, where possible, offer opportunity with contracts and clear terms rather than bailouts. If they wanted to be part of my success, they could earn it like anyone else.

The first part of my plan was simply to stop being the safety net. The second part was to be deliberate about how I would help—if I helped. That meant offering structure: paid gigs, formal contracts, not free handouts.

And that’s how the letters that were meant as truth bombs became the first step in a longer transformation. They were the beginning of a process I could not have started if Victoria’s joke hadn’t blown up in my face. Sometimes the worst things have the curious habit of making your priorities clear.

Two weeks after the last envelope left my hands, I sat in a conference room while Stuart & Associates planned a campaign for Riverside. My phone pinged with angry texts. My mother had been reading; Victoria was frantic; Quinn was embarrassed. But the board offered me an official title and an audience that valued my work for what it was.

I breathed in and let the new life—quiet, professional, and carefully bounded—settle around me. I had mailed the truth. Now I would build new boundaries on its foundation. I would not be the family’s bank. I would be their sister, if they earned it.

Part Two

The morning after the letters were delivered felt like a wake-up call for everyone. My mother’s calls began as a torrent and then became fewer and more precise. My father, who had been silent for years about financial details, called to say the contractor could wait. “We’ll reevaluate the budget,” he said, and for the first time in decades his voice sounded tired rather than just defensive.

Victoria’s reaction was theatrical as expected—Instagram stories half-heartedly apologizing for “family drama” while simultaneously painting herself as a victim of a cruel world. Quinn, the messy sibling who always expected rescue, texted apologies and then, a few days later, a quiet message asking, Can you help me find a group? That message may have been the most important moment. He had been gambling away opportunities for years; finally acknowledging a problem meant there was a chance for real change.

What none of them expected was for the letters to catalyze something neither punishment nor public humiliation could: accountability. The documents forced conversations my parents were unaccustomed to having. Financial advisors were called; awkward meetings about bank statements were not avoided. The family had to look at the arithmetic of their choices.

A week after the letters, my mother showed up at my office unannounced. She held my letter in her hands and read chunks of it aloud like prayers she couldn’t quite swallow. “We raised you to be selfless,” she said. “That’s the real problem.” It was a strange justification: guilt as a parenting philosophy. I told her I did not want to be the family’s checking account, not because I resented helping on principle but because enabling prevented them from growing. She left with a list of appointments to make with a financial counselor.

The family intervention that followed was messy and raw. They came to my apartment—Mom, Dad, Victoria with mascara streaked, and Quinn looking sober and scared. The room filled with papers and old grudges. The conversation cut into old wounds and left them raw: admissions of avoidance, confessions of borrowing without asking, apologies that felt insufficient but necessary.

Standing there, I realized something uncomfortable: truth could be brutal, yes, but it could also be the start of repair. When I played the recordings, shared the bank statements, and walked them through the timeline of favors never repaid, the arrogance that had sat like a heavy blanket over our family began to lift. My mother’s reaction moved from anger to shame. My father shifted from defensiveness to dull comprehension. Victoria yelled and then, in a quiet room after the others left, sat on my couch and cried in a way I had never seen her cry before—no performance, no audience, just the raw wetness of regret.

Quinn’s admission that he had a gambling problem was the turning point for him, and arguably the hardest. He accepted help, privately making a plan with his banks to set up payment plans and signing up for support groups. The relief in his voice when he called me a month later to say he had completed his first thirty days without betting was one of those small miracles that make adult life worth it.

Did the letters hurt? Yes. Did people resent me? For a while. But resentment is an emotion who’s teeth eventually dull if it’s not fed. I had not wanted to humiliate them for sport. I wanted them to face the consequences they had been dodging.

The transformation was incremental, practical, and dull in all the right ways. My father sold memberships and luxury subscriptions. My mother shut down expensive, performative “self-care” subscriptions that were more about social image than health. Victoria took a part-time job at a gallery, learning the ropes rather than imagining herself the next art world doyenne overnight. Quinn entered counseling and began working a steady job that kept him away from casinos.

We started family therapy—not because one dramatic intervention would cure everything, but because a regular forum where we were coached to listen and to accept responsibility seemed like the only sensible way forward. The therapist’s office became a place of small, practical exercises: listening without interrupting, agreeing to small financial accountability steps, and creating transparency with a shared budget app where everyone could see what had been earned and spent.

Three months into therapy, something unexpected happened. Larry came to the house with a folder. He had been called by my parents, he said, but he had also been watching my work long enough to know what I was capable of. “Your family wanted to make sure they understood what they almost cost you,” he said. Then he smiled and told them I had been recommended for partnership track and that several firms had been trying to recruit me for years.

There was a quiet, stunned silence in the living room. My parents understood what ambition without support could build, but they also felt the sting of having misinterpreted my steadiness all these years. They had been comfortable in the roles they had assigned me: reliable, forgiving, always present. They had not noticed, perhaps intentionally, how that role had been weaponized to cushion their mistakes.

Then I announced—calmly—that I planned to start a consulting firm. Not immediately, but in the near future. I told them that if any help was to be considered, it would be as clients or paid consultants, not as unpaid lifelines. I offered Victoria a contract: social media consultancy for a modest, fair fee. If she wanted to work, this would be a real job. Our arrangement had conditions: proper invoices, clear deliverables, and a timeline. No more favors, no more “family first” exceptions. If she couldn’t meet the terms, fine. I’d find someone who could.

It was everything my parents had asked for—help—but wrapped in boundaries they hadn’t expected to meet. My father’s pride in the board’s offer and his willingness to change his golf club nights for reading circles were small but meaningful signals. They showed intention to rebuild rather than simply complain when the collapse happened.

Over the next year, the changes layered on top of one another. Victoria kept her job and slowly built a stable client list. Quinn’s gambling counselor helped him manage impulses and rebuild financial credibility. My parents continued therapy and financial counseling. We instituted household budgets and used monthly meetings to go over expenses—no drama, just numbers. I helped set up a small family fund for emergencies, one that required a committee sign-off (and yes, I created oversight rules—no single person could withdraw without approval). Strange as it sounds, the act of creating a financial structure made them accountable in ways words never had.

My consulting firm launched on a cool autumn morning with a modest client list and a silent partner in Larry. I hired a small team and found that being boss was a little like being the stable sister, only with a sign and the power to say yes or no. That clarity was liberating. I offered Victoria paid freelance work. We signed a contract, she did excellent work, and she collected paychecks on time. Those paychecks meant she could pay rent without asking for a bailout. Pride is a slow lesson, but sanity rewards it.

Forgiveness is a different animal. I never masked the harm that had been done. I did not let the past vanish because payment was made or because apologies were offered. Forgiveness took time and was offered in increments, like the steps Quinn took away from gambling or the months my mother kept to her therapy appointments. It was not an instant erasure.

Sometimes, the hardest moments were the quiet ones. The holidays were nerve-wracking at first. Old scripts—who sat where, who brought what—kept trying to return. But we learned to pause and decide. Cousin gatherings were simpler. No one took my discretion about money as a joke anymore because we had set boundaries and violated patterns had consequences.

At a small dinner—my first holiday back at the old family table since the letters—the changes were both real and tender. My mother cooked and actually listened when Quinn spoke about his group meetings. Victoria laughed without performing. My father put down the wine glass and asked how the consulting firm was going. He admitted, quietly, that he had been wrong. In that admission was a kind of recollection I had longed for: recognition, not for me alone, but for the way he had mistaken stoic loyalty for endless obligation.

My firm grew slowly and steadily. We worked with local nonprofits and small businesses to build marketing strategies that fit a budget and delivered measurable results. I loved the work—the pattern-finding, the execution, the way a campaign could turn an organization into a story with traction. That may sound like the same thing I did at the agency, but now I had control and I had boundaries.

One afternoon, a year after the letters, my mother called to say she had seen something in the newspaper—my street had been recognized for a small business award—and she sounded, for the first time in a long time, genuinely proud without an ulterior ask. “We should have done things differently,” she said. “I should have encouraged you instead of making excuses for everyone else.” I listened. And in the listening, I heard progress.

We still had rough edges. There were occasional reminders of the old dynamics—an offhand remark, a long-forgotten habit—but the therapy and the new habits re-routed them. We set new rituals: monthly family check-ins where finances were discussed transparently, “no guilt” policies about money, and a formal calendar where everyone proposed ways they could contribute to the household. Sometimes they volunteered to cook, sometimes they offered to watch Quinn’s dog for a weekend while his job required travel.

One of the stranger, softer results of all this was the way our holidays changed. Instead of grandiose dinners designed to impress neighbors, we had small, sustainable meals where everyone brought a dish and someone else paid for the special bottle of wine. The point was to be together rather than to perform. Those dinners had a warmth that my parents’ parties never had because they were honest and inclusive, not competitive.

Victoria and I began collaborating on small creative campaigns for local artisans. She learned about contracts and portfolios; I learned about storytelling in a way that made room for vulnerability. She never stopped being dramatic (how could she?) but she stopped confusing drama with necessity. Quinn, now steady in a finance job, occasionally called to ask professional questions instead of loans. He and I actually worked on a small side gig to help a friend’s startup build a budget. He was careful in a way he had not been three years prior.

The pivotal moment, for me, came one humid Sunday when we gathered to clean out the attic. We found boxes of old report cards and clippings—my achievements. “We did notice,” my mother said in a small voice, “we just never reacted the right way.” It’s a confession that stings: acknowledging observation does not mean you acted to lift someone up. But it was progress. We all said things we meant then. The attic’s dust felt like the dust of old agreements we had made with each other and then forgotten.

The letters I had mailed—once weapons in an emotional arsenic war—became a kind of pivot point for our family. They forced us to see ourselves as a system. They made clear that enabling cost real consequences, that being the “fixer” allowed others to stagnate, and that accountability can be the context in which people finally learn to thrive.

I didn’t get the satisfaction of a clean, cinematic revenge. People changed because they had to, not because I wanted to punish them. My parents didn’t lose everything; they were given a chance to rebuild responsibly. Some might argue I should have been softer. Maybe. But if there’s one thing I reject, it’s the idea that family is automatic bliss or that loyalty means being a doormat. It means being honest. It means holding each other accountable when softness becomes enabling.

A year later, at a small dinner my mother cooked (simple food, no fanfare), my phone buzzed with a message from Larry: the board had approved my resignation with an offer to consult as a partner, but more importantly, they’d given me a glowing reference. My consulting firm was stable; Victoria’s social media strategy had brought in a few paying clients, and Quinn had completed his thirty days, then sixty days, then a year of steady work. That evening, the family group chat had an unexpected, modest message from my father: Proud of you all. No attachments, no strings, just a heart emoji.

It might sound small. It wasn’t. The old scripts—“you owe me,” “family helps family”—had been rewritten into something healthier: we support each other with honesty and agreed boundaries. The letters had been the blunt instrument that prompted the surgery. The therapy and the practical changes were the recovery.

When people ask me if I regret writing those letters I don’t pretend it’s simple. There was pain. There was anger. There were moments I felt guilty for tearing a thin fabric that had kept us all in roles we could stomach. But the alternative—continuing as the family’s bank and emotional cushioning—was a slow self-erasure. I chose myself, and that choice allowed my family to choose better, too.

On a cool spring day, I walked past a café that had hosted the first time we’d truly talked money. My phone chimed with a message from Victoria: Coffee tomorrow? I have a proposal. Paid, of course. I smiled and typed, 10 a.m. Maine Street. Sometimes being generous looks like paying someone to do real work. Sometimes it looks like holding boundaries. Sometimes it looks like listening.

The last scene in that chapter of my life wasn’t triumphant or violent. It was ordinary and small: my father calling to ask if I’d come to Sunday dinner, my mother saying something sincere—Bring the dessert, please.—and Quinn’s text, Proud of you, Isa. The group chat was busy but not with demands; it had a heart emoji.

I had mailed the truth in envelopes and the truth made a mess. But that mess turned into work—the awkward, gritty work of accountability, therapy, and rebuilding. Families don’t get fixed overnight, but they can be reformed around honesty. I started my consulting firm not because I wanted money—a fortunate byproduct—but because I wanted autonomy. And what my family got instead of money was—slowly, gradually—responsibility, boundaries, and the chance to be real.

Sometimes the hardest letters you write are to the people you love. Sometimes they need to land with the force of documented reality to wake them. If they are willing to learn, the result can be a better, kinder family. If they aren’t, then at least you’ll know you tried. And that knowledge—quiet and firm—offers a kind of peace you can’t buy or beg for.

As for me, I still have my ledger. It’s just different now. I track contracts, not bailouts. I make offers based on fairness, not guilt. And when the family group chat pings, I look first for the heart emoji, then for the request—and I answer with a contract or a dinner reservation, not with automatic money. They wanted my finances; I chose to give them truth, and what they received in the end was the only thing that mattered: an honest chance to be better.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

My Husband Slipped Sleeping Pills in My Tea—When I Pretended to Sleep, What I Saw Next Shook Me. CH2

My Husband Slipped Sleeping Pills in My Tea—When I Pretended to Sleep, What I Saw Next Shook Me Part…

At Family Party, My Mom Gave Me A Painful Slap – While My Sister Got An iPhone 17 Pro Max. Then I.. CH2

At Family Party, My Mom Gave Me A Painful Slap — While My Sister Got An iPhone 17 Pro Max….

At Family Dinner, My Mom Threw The Bowl At My Face Because I Refused To Pour Wine For My Sister. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Mom Threw The Bowl At My Face Because I Refused To Pour Wine For My Sister…

My Husband Danced With His Mistress at Our Wedding Anniversary, by Morning, He Was Homeless. CH2

My Husband Danced With His Mistress at Our Wedding Anniversary, by Morning, He Was Homeless Part One My name…

At Family Dinner, I Accidentally Saw My Mother And Sister Using My Fake Signature. CH2

At Family Dinner, I Accidentally Saw My Mother And Sister Using My Fake Signature Part One My name’s Veronica….

During the latest taping of The Five, the audience got a hilarious surprise when the atmosphere suddenly grew tense over something seemingly trivial.

During the latest taping of The Five, the audience got a hilarious surprise when the atmosphere suddenly grew tense over…

End of content

No more pages to load