My Sister Fired Me from Our Family Foundation Then Smirked as Our Parents Called It “Fair”…

Part I — The Email, the Seal, and the Silence

I was in the archives of the Helen Hayes Art Foundation, breathing in the familiar sting of varnish, dust, and turpentine that always felt like being hugged by the past, when the email arrived. It was from my sister, Michelle, sent to the entire family council—our father, Michael; our mother, Lisa; and our uncle, Robert—people who had rarely stepped foot into this room unless there were cameras or donors involved. The subject line hit like a gavel:

Board Decision: Foundation Dissolution and Q4 Management Fee.

I read it twice because once felt like a hallucination. The body was crisp and bloodless: The board has voted to liquidate all foundation assets. Irene’s curatorial contract is terminated. Her residency stipend is revoked. A monthly management fee of $10,000 is effective immediately.

Three replies stacked beneath like a chorus line. My father: “Proceed.” My mother: “A difficult but necessary step.” And from Michelle, the kind of single-word mandate she loved: “Execute.”

Execute, I whispered to the quiet stacks of catalogues and provenance binders. Fine.

All the indignities I’d rehearsed in my head—the phone call to plead my case, the draft resignation I’d threatened to submit in my lowest hours, the slow bleed of self-respect—evaporated. Michelle thought she was firing “the help.” She didn’t understand she’d just pulled the pin that Aunt Helen and I had hidden years ago.

“Margaret,” I said, turning to the woman who had spent forty years keeping this collection safe with nothing more than a loop, a ledger, and an incorruptible soul. At seventy-four, she moved like a cat that preferred not to be noticed. “Lock the main gallery doors. No one in, no one out without my authorization.”

She blinked, took one look at my face, and nodded. No questions. Bless her.

I walked into Aunt Helen’s office—my office by inheritance of trust and habit—and shut the door. The desk was mahogany, carved with leaves and curlicues no one makes anymore. I opened the asset management system and pulled up a protocol few people knew existed: the Curator’s Seal. It was a two-key control Aunt Helen and I had designed back when my parents were still pretending to like art because it looked good on holiday cards.

The seal froze the entire internal collection. Nothing could be moved, cataloged for sale, or transferred between rooms without two codes—mine and Margaret’s—entered in sequence within sixty seconds of each other. I entered mine. Margaret appeared in the doorway as if summoned by memory and entered hers. A small green dot pulsed on the screen.

Internal inventory: sealed.

Then the external collection: the sixty percent of our most valuable works that didn’t live under our roof. They were at Fortress in Delaware, where insurance companies go to sleep at night. I picked up the secure line.

“Fortress,” a voice answered, professional to the point of invisible.

“This is Irene Hayes of the Hayes Foundation,” I said, steady as I wished my hands were. “Initiating a full asset lockdown, authorization code Delta Seven.”

A pause, the kind a careful person takes to decide how much trouble you’re about to bring into their day. “Ms. Hayes, Delta Seven is a full-stop freeze on Vault 7C. Confirm?”

“Confirm. Effective immediately. All access requests are denied, regardless of who they come from. That includes the operating board.”

“Understood,” he said. “Vault 7C is under preservation seal.”

I hung up to a sudden symphony of ringing. I let it play. My mother called first. I watched her face flash across my screen, then darken into voicemail. “Irene, what do you think you’re doing? You’ve locked the archive accounts. You’re making a mess.”

My father’s voice followed, clipped and righteous. “I don’t know what game you think you’re playing, but it stops now. Your uncle and Michelle have worked on this liquidation for a year. You are embarrassing this family. Be a professional.”

Be a professional was funny coming from a man who thought provenance meant the guest list at a fundraiser.

A text from Michelle arrived—the Queen decreed by keystroke. I don’t know what you think you accomplished by calling Fortress. Our lawyers will break the seal by morning. You’re only making this harder on yourself. You have 24 hours to vacate the apartment before we change the locks.

I typed back, fingers suddenly calm. The apartment is part of my curatorial contract. And the art belongs to the foundation, not to you.

Dots. Then the message I didn’t know I’d been waiting for since I was old enough to differentiate a Sargent from a print of a Sargent: You are the foundation we’re dissolving. You’re not family, Irene. You’re just the help. The help is being fired.

There it was. The green light. Not an insult. Permission.

By morning, I wasn’t at the apartment they believed they could reclaim. I was in the leather-bound office of David Fields, Aunt Helen’s estate lawyer, who had known our family before names like “management fee” became a euphemism for siphoning.

“I’ve been waiting for this call for three years,” he said gently, waving me to a chair. “Helen told me this day would come.”

I slid the printed email across his desk. “They voted to liquidate the collection. Terminated my contract. Can they do this?”

He put on reading glasses like armor. “They can try,” he said, and turned his monitor for me to see. “Helen structured the foundation in two parts. Your family runs the operating board—day-to-day, budgets, payroll.” He looked over the lenses. “They can terminate you as curator. They control operations.”

I felt the floor tilt. “So they win.”

“No,” he said. “That’s where they made their mistake. They confused operations with ownership.”

He opened a heavy file. The scanned document looked like it still smelled of ink. “Helen created a second entity,” he said. “The Preservation Trustee. Absolute veto power over the disposition, sale, or liquidation of any asset. They can’t sell so much as a picture frame without the trustee’s written approval.”

“Who is it?” I asked, even as my heart answered.

David smiled and tapped the signature page. “You are.”

I stared at my own name, tucked into a place no one would look. “I never signed this.”

“Oh, you did,” he said. “Page forty-two, Appendix C of your employment contract. Buried, because Helen was not merely brilliant—she was suspicious. She hid your authority in plain sight until they showed their hand.”

It took a second to breathe around the sudden size of the room. “So they can fire me as curator, but—”

“But you are the Preservation Trustee,” he finished. “You own the kill switch.”

He picked up his phone. “Shall we send them a cease-and-desist?”

When David’s letter hit, the ringing stopped. Silence—the hiss that happens when a balloon decides to become a piece of rubber again. But David wasn’t smiling yet. He had a pen in his hand and a ledger on his screen.

“The letter freezes liquidation,” he said. “But look at this line item. A wire for $150,000 to Fine Art Restoration Services.”

“I never authorized restoration,” I said. “Who are they?”

“An LLC created last year in Delaware. No public-facing business.” He met my eyes. “Irene, I think your sister has been skimming.”

The nausea that started in my stomach spread slow and cold. “Or worse,” I said. “Much worse.”

Part II — The Ledger, the Loop, and the Lie

We walked back into the climate vault like doctors walking into an ER without sirens. The Degas and Cassatt sketches that had been Michelle’s sudden obsession last year hung in their usual place—six fragile windows into movement and light. Margaret pulled on white cotton gloves and eased one free.

“Raking light,” she said softly, angling the table lamp to sweep across the paper. “Always tells the truth.”

Up close, paper is a forest of fibers. The right texture feels old in a way your fingers recognize before your mind does. Under raking light, genuine charcoal leaves a dust that settles into tooth like a secret. Margaret looked. She didn’t speak. Then she took her loupe from her apron pocket and pressed it to her eye.

Her hand trembled. “The paper is wrong,” she whispered. “Too clean. No deckle. And there’s—” She stopped because the word she needed would break something.

I took the loupe and saw it because she’d taught me how to see. No charcoal dust embedded in fibers. No fragile scatter of graphite. Instead, a microscopic pattern of dots—an excellent, terrifying dot matrix. A print so good it believed itself.

We pulled all six. All fakes. Museum-quality reproductions, the sort you use to trick the careless and comfort the greedy. The $150,000 “restoration” was the bill for a swap, not a cleaning.

“She stole the originals,” I said. “Replaced them with prints. And the liquidation—the grand Sabe’s auction—wasn’t just a cash grab. It was a cover-up. She planned to sell fakes before a real expert got close enough to humiliate her.”

“And to bankrupt the foundation first,” Margaret said, voice low. “So you couldn’t fight.”

I called David. He did not swear. He made three phone calls and then put his hand over the receiver. “Two detectives will come quietly,” he said. “They’ll want to see the fakes in situ and the paperwork. Don’t confront anyone yet.”

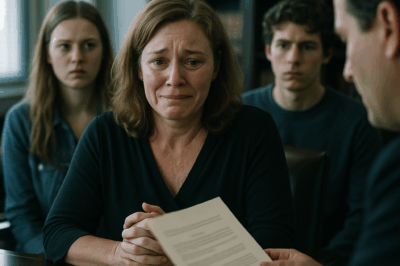

We didn’t have to. Michelle stormed the gallery like a woman who believed doors opened for her because anger needed room. My father, my mother, and Uncle Robert followed, clutching printed cease-and-desists like party favors.

“What is this circus?” Michelle demanded, voice echoing off plaster and frames. “The Preservation Trustee? Who do you think you are?”

“The person Aunt Helen trusted,” I said. “The person who can keep you from burning down her life’s work because you’re cold.”

“You’re done here,” my father barked, pointing. “We may not be able to sell the art, but we still run this place. The operating board voted. You’re fired. Pack your things and get out of your aunt’s apartment.”

“Actually,” David said, stepping forward with a politeness he sharpened like a blade, “you can’t fire her. Clause 14B grants the Preservation Trustee full veto over all board decisions relating to assets, personnel, and facilities. You can’t change the locks. You can’t alter the staff. You can’t do anything without her consent.”

Michelle’s cheeks drained from righteous pink to the ash of comprehension. For the first time in my life, I saw her mind calculate a future in which she didn’t win.

“But that’s not why we’re here,” I said, and nodded to Margaret. She set one of the framed sketches on an easel beneath unforgiving light.

“It’s beautiful,” I said. “A perfect copy. Michelle, how much did it cost? A fraction of the $150,000 you wired to your shell company?”

My mother’s voice came out small, lost. “Embezzlement? Irene, what are you—”

Michelle’s mask cracked like sugar under a spoon. The executive voice vanished; the pleading girl we used to share a room with tried to stand in its place. “Irene, please. This is family. We can fix this. We can—”

“You fixed it,” I said. “In writing. You called me not family. You called me the help.” I turned to David. “Tell them the rest.”

He lifted his phone. “Michelle Hayes,” he said, voice even. “We have documented evidence of wire fraud and grand-scale art theft. We have the swapped works and the forged invoices. We’ve informed the authorities.”

That was when the gallery doors opened again, this time with a careful quiet—the sound honest people make when they enter a museum. Two detectives in suits stepped inside.

“Boston Police, Art Crime,” the taller one said. His eyes found Michelle as if he’d been introduced to her long ago. “Ms. Hayes, you’ll need to come with us.”

My mother made a small sound I will hear when I am old. My father sat, all air gone from his case. Michelle didn’t fight. She looked at me just once, and the look wasn’t apology. It was shock that the world she’d rearranged around herself had refused to obey for the first time.

They cuffed her and walked her out past the paintings she’d described as “assets,” past the photographs Aunt Helen called “friends,” past Margaret, who had once taught her the word chiaroscuro and gotten an eye-roll for her trouble.

When the doors closed, the gallery was so quiet I could hear the minute hand move on the old brass clock. Then I breathed out a lifetime’s worth of air and felt my knees again. David touched the table with two fingers like it was a living thing. Margaret removed the gloves and slipped them into her apron pocket, as if she might someday need a relic to remind herself it had been real.

Part III — Courtrooms, Vaults, and the House of Cards

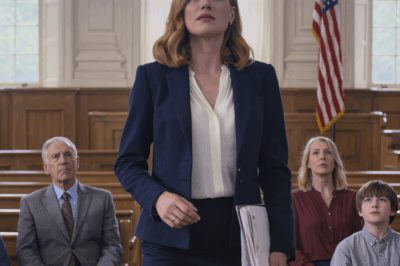

The trial moved faster than I expected and slower than I wanted. Wire fraud leaves a trail; art theft leaves ghosts. The prosecution followed both, one document at a time, until the story they told was a road with no exits. Michelle’s shell LLC had been “Fine Art Restoration Services” in Delaware, but the bank transfers bounced through accounts in Zurich and then to a private vault in Geneva where climate and secrecy are both commodities. A liaison from Interpol’s Art Crime unit sat at the end of the second row and took notes with a pen that made no sound.

We recovered four of the six originals she’d swapped—Degas tracing the rehearsal of a hand, Cassatt catching a woman in the half-breath before she spoke, a Renoir study Aunt Helen never displayed because it felt too intimate, and a Whistler chalk that looked like a whisper on fog. Two pieces had slipped into the black market the way money slips out of pockets you thought were zipped. We put their images on registries and whispered their names into databases that remember forever.

Michelle’s attorney tried everything. Misunderstanding. Delegation. “It was a consultant.” “It was an aggressive preservation schedule.” “It was paperwork.” The defense withered under a simple, brutal reality: most criminals commit crimes like they’re filling out forms. The forms were elaborate, yes, but they were still forms. Dates. Signatures. IP addresses. An invoice number that matched a wire that matched a vault access log that matched a surveillance frame of my sister lifting a crate with manicured hands.

When she spoke, it was to say she was misunderstood. That her ambition had been twisted into a motive. That she’d taken financial responsibility no one else would. The prosecutor listened, then leaned into the microphone. “You were understood perfectly,” she said, not unkindly. “That’s why we’re here.”

Guilty on twelve counts. Sentencing that made headlines for the right reason, for once.

My parents emptied accounts paying legal bills and public relations people who still believed spin could make smoke look like fog. They sold the Victorian in Boston that had been a museum of their most flattering angles and moved to Florida where sunlight can be a balm, a punishment, or both. They called sometimes; we spoke in sentences that kept to weather and doctors and plans to travel that always stayed plans. There was love still, but not the kind that trusts itself to stand on arguments.

As Preservation Trustee, I dissolved the operating board that had treated the foundation like a family business with better lighting. I formed a new one—an artist, a public school principal, a historian who still wore ink on her fingers, a community organizer who had never stepped into our gallery until we invited local students and fed them pizza while they stared at brushstrokes like they were decoding weather. I put Margaret where she should have always been: Head of Archives, with a salary that made a nurse nod in approval rather than snort.

We turned the gallery into what Helen had always tried to make me see when I was a teenager who thought museums were quiet places where adults went to whisper: a classroom without a bell. We opened free Thursday nights and let a jazz trio set up in the corner like the room had always been waiting to breathe like that. We added labels that explained technique and labels that explained who had been kept out of rooms like this for a hundred years. We started a fellowship for students from the public schools down the block, paid them to learn, and watched their hands learn the weight of a pencil as if it were a new instrument.

I went to thank Fortress. The manager who had taken my Delta Seven call stood to shake my hand. He didn’t smile; he nodded like a person who understands gratitude and refuses to make it expensive. “Your aunt prepared well,” he said. “Most don’t.”

“Was she… paranoid?” I asked.

He thought about it. “She was realistic. That looks like paranoia from the outside.”

Realism has a cost. Aunt Helen had paid most of it. The rest was due the day Michelle hit send.

Part IV — The Golden Child, the Scapegoat, and the Ghost in a Frame

A few weeks after the verdict, I sat in David’s office again, unable to shake a question that hung in every room like stale perfume. “It wasn’t just money,” I said. “Why did she need to destroy me to get it?”

David folded his hands. He had the voice of a man who had delivered terrible news kindly for four decades. “It’s a classic tragic dynamic,” he said. “Golden child and scapegoat. Michelle’s identity was built on being the winner. To win, she needed you to lose. The foundation was an ATM, yes, but more importantly, it was the one place you were better without argument. Taking it wasn’t enough. She needed to prove you were nothing without it.”

I thought of childhood Thanksgiving dinners with seating charts like strategies and praise assigned like bonuses. Michelle collected trophies; I collected stray compliments like nickels on a sidewalk. Aunt Helen gave me something more durable: keys, literal and otherwise. She taught me how to call wind in a gallery with no windows—how to feel the draft when someone opens a door in another room. She taught me that art has a spine and that people do, too, if you stop letting other people hold your head.

“Even if she stole the collection,” I said, “the part that would have fed her forever wasn’t money. It was the story.”

David nodded. “You changed the ending.”

Later that day, Margaret came to my office with a brown-wrapped rectangle, not much bigger than a placemat. “Found this in Helen’s private storage,” she said softly. “Not worth anything. Except…” She turned it and showed me the note in my aunt’s strong hand. For Irene.

It was a small seascape Helen had painted in college—a student’s work, the horizon a little too straight, the water too obedient. Some brushstrokes were timid; others, brave. It was terrible and honest, which made it priceless.

I hung it above my desk where the Degas study might have gone if life had been about money. The little harbor looked back at me all day like a secret I kept finally where it could be seen. When donors came in, they stared at the small painting and tried to find the signature that would justify space on that wall. I didn’t explain. I simply watched who smiled first, who squinted, who asked.

The calls came—journalists, disappointed friends of my parents, people who wanted a salacious angle and people who wanted to know how to keep their own families from breaking art like a piggy bank. Most I redirected toward the policy page on our new website, where we’d posted everything: governance, accountability, inventory protocols. Transparency is a disinfectant and a dare.

One morning, an email arrived from a woman I didn’t know, subject line: We were wrong. It was from a former board member of a museum across town, a person who had once sniffed at our little gallery like it was a nice boutique. I read the paragraph twice and then saved it because sometimes apologies need to be archived like rare books.

The new board met in the gallery after hours, the room lit like a promise instead of a stage. We argued—good arguments, the kind that end in better. We disagreed about wall text and school bus schedules and the ratio of contemporary to historical work. We took turns losing and then thanked each other for it.

On the night of our first re-opening, I stood in the doorway and watched a bus arrive from a middle school seven blocks away. The kids came in with the noise they’re supposed to make. A girl in a denim jacket stopped in front of a Cassatt and said, to no one, “She looks like me.” A boy with hair like a question mark stared at a Mapplethorpe print and didn’t know where to put his hands. A teacher who had been paid too little for too long tilted her head and almost cried because she hadn’t seen a painting since she’d been a girl in a different city that changed her forever and she’d forgotten how hard it can be to stand in front of beauty and survive it.

Margaret moved among them with a smile she kept for children and genuine adults. She held out her loupe and said, “Want to see how paint dries?” And six kids leaned in, eyes wide, to witness time.

Part V — A Clear Ending

Sometimes, in the blue before noon, I think about the moment Michelle wrote, You’re not family. You’re the help. I think about how many people build their lives around a word and then wield it like a cudgel. The older I get, the more I respect help as both a noun and a verb. It implies work. It implies humility. It implies showing up.

Months after the trial, a letter found its way to my desk. The return address was a Swiss P.O. box I knew too well. Inside, one page. A man who had brokered for Michelle, now very interested in cooperation, explained that a private collector had turned in one of the missing originals after seeing our registry alert. The piece had been wrapped and hidden inside another frame for safety; guilt—or fear—had done what law often cannot. The drawing returned in a diplomatic pouch, a thing I never thought I’d watch, and Margaret cried openly for the first time since the arrest. One left unaccounted for—a wound I will keep dressed and uncovered because some scars need air.

My parents visited once. Florida had changed their skin and the way they looked at rooms. My mother brought oranges from a roadside stand and a cake from a bakery that survived by selling sugar to retirees. We sat in my apartment above the gallery, a place Michelle once told me didn’t belong to me, and ate at my kitchen table.

My father looked at the Helen seascape and didn’t ask who painted it. He asked if I was happy.

“I am,” I said. The truth tasted like a thing that had been aged correctly.

They left the next morning with a bag of catalogues and a schedule of school tours we’d started to post like a proud parent’s calendar.

The board voted to name the education wing after Margaret, but she refused. “Name it for the kids,” she said. “I’m old enough to know better.”

We held an event for the people who keep places like ours alive—the facilities crew, the security guards, the cleaners, the woman who brings flowers without charging because she likes to see herself in a nicer room once a week. I stood up at the end and said, “Thank you, help,” and watched a hundred spines lift.

People ask me for advice now. It still surprises me. They ask how to write bylaws with teeth and hearts, how to lock vaults so thieves and egos stay out, how to survive a family that calls betrayal a business decision. I tell them we did three simple, hard things: we wrote our rules before we needed them; we hid our failsafes where greed wouldn’t look; and when the day came, we put the truth in writing where everyone could see it and then stood still long enough for it to do its work.

Sometimes, after the last tour leaves and the guard clicks the deadbolt with a sound that used to mean anxiety and now means rest, I walk the gallery alone. Light behaves differently when a room is empty—brave, like it’s rehearsing for an audience. I stop under the clock and listen for the minute hand. I imagine Aunt Helen behind me, not as a ghost but as a habit. I imagine the language we invented together—the seal, the ledger, the smile that told me I wasn’t crazy to believe in a room like this.

I spent a long time being the invisible one in my own family. It turns out invisibility is a kind of training. You learn to see what others don’t. You learn where to hide the key. You learn how to move while people are busy watching themselves.

Michelle will be out someday. Consequences have calendars. But the gallery will still be here, because it was built correctly in the end—on stone, not on smiles. The children will still come and point at brushstrokes and ask why the light looks like water and why the water looks like glass, and someone will hand them a loupe and say, “Look closer.”

I climb the stairs to my apartment—the one that is mine not because paper says so but because I earned it by refusing to leave—and pause at the landing to look at Helen’s little harbor. It is still imperfect. It is still the best thing I own.

We are, at last, what we were supposed to be: a foundation that preserves art, not an artifice that preserves ego. The people who called me help were right. The difference is that now, help runs the house.

And as endings go, I prefer this one: clear, quiet, and complete—the lock engaged, the lights dimmed, the gallery at peace.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will

After My Husband’s Death, My Stepchildren Wanted Everything—Until My Lawyer Revealed The Real Will Part One I never thought I’d…

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night

When My Husband Called Me “Just A Burden” After My Surgery—I Changed Our Estate Plan That Night Part One…

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement

Husband’s Pregnant Mistress And My Sister Showed Up At My Birthday—Then I Made An Announcement Part One I never…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then…

My mom slapped me at my engagement for refusing to give my sister my $60,000 wedding fund, but then… …

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead

Too Ugly for My Sister’s Wedding, So I Became a Lingerie Model Instead Part I — The Test Shot…

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything

My Family Mocked My Law Degree, Until They Discovered I Won The Case That Changed Everything Part 1: The…

End of content

No more pages to load