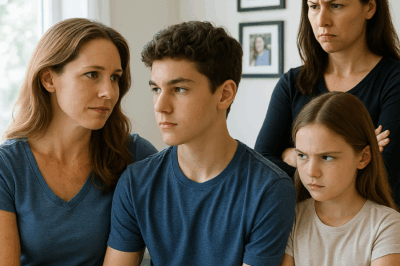

My sister dumped her baby on my doorstep then disappeared; my parents said, “She’s your burden now.” Ten years later, they sued me for custody claiming I kept them apart. But when I handed the judge a sealed folder his eyes widened. Then he asked, “Do they even know what you have?” I just nodded and got ready to speak…

Part One

The knock on my door was soft enough that I almost ignored it. It was just before dawn; the world outside was that particular blue that happens when night stubbornly refuses to let go. I shuffled to the peephole, hair still in a tangled knot, and opened the door to find a wicker basket sitting on the stoop. A blanket was tucked over the handle. I remember thinking, briefly, of a forgotten delivery, of a careless neighbor. Then the rustle of linen and the high, bewildered wail broke the morning open.

She was there—my sister—with eyes hollow from a night spent running, from fear, from something I could not name at the time. She looked at me like a refugee, like someone who had crossed the border of her own life and expected exile to be shelter.

“You’ll take care of him,” she whispered, as if the words were a spell. They were a soft plea and a desperate command wrapped together. Her voice trembled. “I can’t. I’m sorry. Please. Don’t let them—” She pressed the bundle into my arms. Four small fingers curled around my thumb. For a moment all the noise in the world fell away and the only real thing in the room was the weight of that child and the small, permanent pressure of his tiny hand.

She left before I could ask the obvious questions—questions about plans, about hospital bracelets, about phone numbers. She vanished into the hush of the early morning and into the fog of choices that would define both of our lives.

I was twenty-one. I had a secondhand sofa, student loans, and a part-time job that paid enough for ramen and rent—barely. I had never imagined I would be a mother. I had never imagined I would be anyone’s refuge, certainly not for a child who had a mother and grandparents who, by all accounts, were sane and organized and, as I later learned, proud of their appearances.

My parents were not proud of me. They had a careful, curated reputation in our town—volunteers at the church, regulars at the country club luncheon, people who presented their lives as tidy catalogues. When that small, crying bundle appeared in my kitchen, their reaction was swift and clinical.

“Put him in his carrier,” my mother said when she finally came by a day later, but she did not look at him. She stood on the porch as if she were considering whether to step into a stranger’s living room. “This is not what we expected,” she added without apology, smoothing her cardigan as if she were straightening a crease in an endless gown of propriety.

“Take him to a hospital. Call social services. Do whatever you must, but don’t make me the parent.” My father’s voice was colder than the November wind. “You can’t keep him. He is her responsibility. She abandoned him at your doorstep. You accepted him—you have to manage.”

Their words were crystalline in their cruelty. “She’s your burden now,” my mother said in that same detached tone, pronouncing a verdict as if she had consulted a ledger. It was all thinly veiled contempt: for the baby, for his mother, for me. They left with their moral superiority intact and the quiet certainty that they had chosen the right side of history.

What they didn’t account for—couldn’t account for—was what it felt like to cradle someone else’s life in your arms and watch him breathe slow and safe. The child’s tiny chest rose and fell. He smelled of warm milk and milk-sour breath and something like future possibility. His eyes, when they finally opened, were a pale grey and bright as glass. He looked at me with the curiosity of someone who had been handed a world and wondered where to begin. I learned to change diapers at two in the morning, to hold him close through fevers, to whisper nonsense songs until he fell asleep against my shoulder.

We stuttered and stumbled for the first months. There were forms and pediatricians and the small humiliations of being a twenty-one-year-old single woman on the phone with welfare caseworkers. There were nights when I fell asleep on the couch, box of cereal half-crushed on the rug, and the baby’s tiny weight across my chest anchored me in a way I never expected.

My parents, mercifully for the baby and disastrously for us, were gone most of the time—physically and spiritually. Birthdays passed without calls. They feigned busyness when it came to visits. They traveled, they hosted, they “had dinner with friends.” They offered a kind of moral scolding from a distance: the odd text about responsibility, thinly veiled recriminations that my choices would ruin my life. But they didn’t lift a finger.

When my sister left the night she did, she left with a letter that I later found folded under the lining of a coat. It was a hand-scribbled map of panic: threats she claimed they had made, menacing phone calls, pressure for a shame-free marriage and a clean, discreet solution to the “problem.” The letter said one thing that broke me: she wasn’t leaving because she didn’t love him; she was leaving to save him from the people who raised her. The pages were a frantic, slanted mix of guilt and fear. She signed it with nothing but urgency.

I kept that letter in a shoebox with my tax forms and a cracked Polaroid of us three girls at our grandmother’s seventieth. It comforted me in a brutal way. It told me that the reason she had stepped into the night was not because I was supposed to raise her child; it told me that she had been fleeing something darker.

Years passed. The baby—my son—grew into a boy with a shock of near-white hair that shone in the sun and a laugh that could shatter a room into pieces and put it back together. The small town watched for a while. Gossip is a low-burning ember in places like that. People took up their own quiet positions—some pitied me, some whispered that I was reckless, others, blessedly few, gave us casseroles.

I worked. I did the small, repetitive miracles that keep ordinary life moving: teaching Sunday school in the afternoons, taking night shifts at the supermarket, saving every tax refund. I learned to patch knees and soothe nightmares and explain what a word meant when he asked: “Why did Auntie leave, Mama?” My answers were careful threads. I said honest things in small doses and wrapped them in warmth.

When he was four, an acquaintance from our church—someone who’d seen me with my son at the bake sale—came to me with a nervous, half-asked question. “Your mother,” she said, “she’s been asking about your boy.” I sat with my coffee until it cooled. Months later, the calls started—tentative, cousinly-sounding, perfunctory. “We miss him,” my mother would say. “The family wants to visit.” It was a script they rehearsed. Their timing was perfect in its opportunism: grandparents suddenly discovering grandchildren when those grandchildren had learned to be proud without their presence.

They wanted access. Not because they had missed him; they missed the shape of our family that made their lives look better. When we refused to let them walk back in on their terms, they dug in their heels and, in a gesture that seemed like the final indignity, they filed for custody. They accused me in a polite, legally precise way: I had alienated the child, prevented their relationship, and refused to allow them a place in his life. The audacity was not just crushing; it was strategic.

The first time the papers came, I sat on my kitchen floor and read them until the letters blurred. In clinical, neutral language, my parents alleged that I had intentionally isolated our son, withheld contact, and corrupted his relationship with his maternal family. They invoked the language of neglect and then defined it as the care I had provided. In court they would present themselves as betrayed elders, denied access to the simple moral rights of grandparents.

There were moments of anger—hot, sharp—and nights when my eyes burned from crying. But I had a job to do. I had stitched our life together out of cotton and coffee and cheap toothpaste; there would be no unraveling. If they wanted to go to law, then I would answer them with everything I had. The thing about small-town reputations is that they look like barricades until you remove the bricks one by one.

I began to gather evidence as one would gather stones before constructing a wall. Letters that my sister had written, hidden in drawers because she had been too raw to tear them up; the frantic text chain to a friend in another state who’d helped her leave; a couple of voice mails where my sister’s fear leaked into the receiver. I dug further. There were records—phone logs showing days my sister had called without answers because the adults had made sure she couldn’t get through, calls my mother had traced and dismissed as “drama.” I found a string of emails between my sister and my parents months before she fled, where she begged them for mercy and proposed arrangements that would have been humiliations: quick marriage, public forgetting, silence over the truth. In other messages they advised her the opposite: “Keep the family’s reputation intact,” they wrote, “and the rest will be handled.”

I copied everything, printed extra sets, and placed them in folders with labels like “Threats,” “Abuse of Power,” and “Desertion.” I became clinical. Every photograph I had of my son with bruises—benign at the time, unexplained—went into a folder that the pediatrician notarized. A medical report about the early signs of stress in my son’s behavior when he was with extended family was sealed with a stamp. It was ugly, bureaucratic work.

Meanwhile, my parents continued their performance—visitors to the country club who mentioned their concern for grandchildren in the same breath they described that new vacation home. Their calls became more persistent when my son matured into an intelligent and polite child, the kind people wanted to be associated with. They wanted proximity not connection. They wanted to be seen in his presence as a testament to their good parenting, as if their conscience could be cleansed with a family photo.

When the custody papers arrived, I didn’t panic. I sat with my lawyer—a woman with a severe bob and an empathy that was warm but not sentimental—and we went over the file. She leaned back and said, “They want him because he is your success. They don’t want to be grandparents; they want to be vindicated.” She had a way of making things feel sensible by naming them plainly.

So I prepared. We called witnesses: the neighbor who had noticed my sister running with a duffel bag the night she disappeared; a friend who had kept the letter my sister had left in a shoebox; therapists who had worked with my son during nights of sleepwalking and teeth grinding and had documented stress responses tied to being under their grandparents’ roof. I subpoenaed records showing that my parents had known of the allegations in my sister’s letter and had dismissed them. It was surgical: each piece connected to another; if one collapsed, the structure might still stand.

Still, legal fights are messy and ugly and public. The first time my mother sat across from me in a waiting room of the courthouse, she looked composed, a practiced lady wearing pearls. On her lap she carried an envelope. She smiled in the way people do when they are certain they are doing right—like a person holding a catechism. I wanted to stand and scream. Instead I thumbed through my folder and felt the weight of what I had: not vengeance, but evidence.

My son sensed the tension. Children are astonishingly aware of the bones of decisions being made around them. He clutched my hand in the courthouse hall and asked, quietly, “Mom, will they take me away?” I knelt in front of him and looked him in the face. “No,” I said, and the word was a promise. I had raised him through storms because I believed that family was not the people who shouted the loudest but the people who stayed when no one else would. He was mine—my choice and my responsibility.

When the hearing was scheduled, the small courtroom was full of that sweet tension you always get in legal dramas—people leaning forward, the cool air, the subtle rustle of paper. My parents arrived flanked by their own allies, a collection of neighbors and acquaintances who had been ready to accept their narrative without asking for documents. They looked at me like I should be apologetic. They looked at my son like he was a prop in their drama.

I sat there with my folder in hand. Inside, the pages were neat, labeled, and organized in a way that would make any auditor nod with grim approval. What I had learned over the decade was that the truth is a patient machine; if you feed it evidence in the right order, it hums.

The judge entered with the slow, deliberate gait of someone who has been entrusted with a certain kind of authority and is tired of seeing petty wars in a room that should be calm. He asked the usual things: reasons for filing, the history of the child’s care, the relationship with extended family. My parents spoke first. They offered the practiced line: “We want to be present in his life. We love him and believe grandparent-grandchild bonds are critical.”

Their words were tested by their own silence over the past decade. They had the gall to claim their love had been stifled by me, the woman who had raised the child they pretended was “theirs.” Suddenly the room felt small; their self-importance like a house with thin walls.

When it was my turn, I let my lawyer begin. She called witness after witness with calm, careful questions: the neighbor who’d seen my sister run away and who had a photo of a duffel bag being hurried down the road; the therapist who spoke of chronic stress markers; the friend who had hid my sister for a week—afraid to be found yet willing to preserve the truth—and who had copied the original letter in case the need ever became a legal matter. Each testimony was a thread. Each thread, when they were woven, was a rope.

When the time came for me to speak, I rose and felt something like the room exhale. I told them the story: the knock on my door, the weight of an infant, the letter with the words “Don’t let them near him,” the years of absence. I showed the judge the first pages: my sister’s scrawled notes, the email prints of threats, the hospital records documenting early signs of stress. I explained, carefully and without drama, the way my parents had maintained a public air of grandparental grief while privately advising a course that would erase scandal rather than protect a child.

Their faces when the letters were read were remarkable to behold. The smugness drained, replaced by the pale wash of people who had discovered that the map of their comfortable lives had a hole big enough to swallow their reputation. They muttered. The force of their own paper confession—pages where my sister wrote of threats, of coercion—hit them where pride lives: their public image.

By the time I pushed the final document across the judge’s bench, the room had changed. Shock is an oddly physical thing. My father’s hand, usually so sure and taut with moral claim, trembled. My mother’s pearls were suddenly a clumsy mockery of their moral costume. The people who had come to crown them were quiet as if someone had lifted the orchestra while a single instrument strained to play the wrong note.

I slid the sealed folder forward across the scarred oak bench with the quiet of someone setting down a book at the end of a long read. The judge hesitated for a breath—an invitation, perhaps, to let the room figure themselves out. He opened the folder. His eyebrows rose; he glanced toward my parents. Then, in a voice that contained equal parts curiosity and the hush of responsibility, he asked me the most disarming question: “Do they even know what you have?”

They didn’t. They had never had the curiosity to search. They would never have guessed the significance of the paper in front of them. The folder contained not only the letters and the documents; it contained a meticulous chronology, a timeline of silence, and a small, seismic piece of truth: the record of threats and calls and of the cover-up. It made the case not about grandparental love but about abandonment and neglect disguised as propriety.

When the judge looked at me again, his face had turned from solemn to an odd combination of righteous displeasure and the humane kind of pity. He closed the folder. The gavel sounded. The words the court would record were simple and decisive: custody would remain with me. My parents’ claim was denied.

They left the court with the same rigid gait they had arrived with, except now their faces carried not superiority but something like stunned disarray. They had believed the law to be a tool they could wield; instead it had become a mirror.

I held my son’s hand and we walked out into an afternoon that felt washed clean. He climbed beside me, small and steady, and said what children say when they have survived something confusing. “We did it, Mama.” His voice was like sunlight on cold water—warm, clear, and brave.

Part Two

In the months after the hearing, the town had its own quiet reckoning. People whispered less, or maybe they shifted their gossip to safer topics—gardens, weather, lunches. My parents tried their performance acts for a while. They wrote passive-aggressive notes and attempted to guilt my son via third parties. They tried to be the sort of grandparents who appeared at opening nights and recitals, clutching their hands like a badge. But their presence had been disqualified by their prior choices; proximity after neglect isn’t redemption.

I spent those years building boundaries that were firm but not cruel. It would have been easy to lock the door and post a sign: Do Not Disturb. Instead, I set up rules: visits would happen if they respected therapy recommendations, if they read parenting materials suggested by the child protection team, and if they admitted nothing but asked questions in good faith. They balked.

They argued over the petty things—why I had kept certain photographs from the family album, why I had not invited them to the last birthday. They said I had made them suffer. I looked at them and thought about the shoebox with the letter. There are two kinds of suffering: the one you choose and the one you create. They had chosen the former; they wanted compensation for it. I had found no room in me for that sort of trade.

Ten years after that early morning knock, after nights of diaper changes and school projects and scraped knees and science fairs, they sued again. This time the complaint alleged that, over the decade, I had deliberately estranged my son from his maternal family, obstructed contact, and prevented bonds that would have connected him to blood. They claimed my resistance to their late, dramatic returns was willful alienation. In short, they wanted custody retroactively reexamined and their legal access enlarged.

Court dates are strange mirrors; like repeated plays where people re-enact themes, hoping the audience will applaud. The courthouse greeted us with the same wood scent and low hum, but this day there were new faces—people who had not been present before. My son sat beside me, older now, thirteen, and his knees were a little long in his jeans. He had the same pale, intelligent gaze. He had been coached gently to summon facts, to speak calmly, to tell the truth. He was no longer the child of desperate nights; he was a young man who had grown with my love and with a conviction about what family meant.

When the judge called the case, my parents’ legal team opened with performative grief. Their lawyer, practiced in the arts of empathy as leverage, painted pictures of family reunions denied and grandparental rights trampled by a stubborn daughter. The crowd watched, curious, and the judge listened with the slow concentration of someone guarding the law.

Then it was my turn. I had with me a folder—a sealed folder—that was thicker than the rest. My lawyer placed it on the bench like a final instrument of truth. I had been careful over the past decade; I had kept everything: receipts, records, school notes, therapy logs, and yes, the original letter that explained why my sister had fled. But there was more.

There are moments when you need to show not only words but the trajectory of choices. The sealed folder contained not only the original letter—handwritten and raw—but also a set of corroborating documents: bank records showing suspicious transfers, text messages where themes of manipulation appeared, phone logs showing a pattern of adults cutting off lines of help, and statements from distant relatives who testified that they had been urged to stay silent. I had also included a carefully documented chronology of my parents’ calls: days of absence and then sudden, opportunistic calls when my son had achieved things that would reflect well on them. It was a dossier that did not aim for vengeance; it aimed to build a narrative the law could not ignore.

When the judge opened the folder and glanced at its contents, there was a tiny, almost imperceptible intake of breath. He looked up at me and asked, quietly, “Do they even know what you have?” His voice was not accusing—rather it was incredulous that a family could be so blind.

I nodded.

The courtroom’s atmosphere shifted. The judge, who had presided over hundreds of custody cases, seemed to appreciate the weight of what families constructed and what they destroyed. He read aloud some of the documents: passages from the letter where my sister wrote about being pressured to conceal her pregnancy, excerpts of texts where she begged my parents to intervene to keep the child safe, and contradictions where my parents claimed ignorance at times when they had been clearly in the loop. The reading itself was less important than the fact of it—the words existed. The truth, when placed in official cotton, stops being rumor.

My parents’ lawyer tried to stand on principle, arguing that time heals and that courts should presume that grandparents should be given access if it’s in the child’s best interest. He invoked vague things like “family unity” and “the child’s right to know his lineage.” The judge listened, but his eyes returned to the records again and again. Evidence matters.

I spoke next with what amounted to a simple argument. I told the court that my decision to limit contact had not been borne from spite but from necessity. I explained the years we had lived under the shadow of the letter, the documented threats to my sister, the way their priorities had placed social reputation over a child’s safety. I told them about the nights the boy had marched in his sleep, about the anxiety that came when we changed schools, about the way he had now formed a stable set of relationships that would be harmed by sudden, traumatic reintroductions. I handed the judge the sealed letter, then sat back down.

He looked at my parents. For the first time, perhaps, they looked small. My father opened his mouth, tried to argue the specifics, but the judge cut him off.

“Your claim rests on rehabilitation,” the judge said, writing. “You allege a desire to be part of the child’s life, but you cannot expect a court to ignore a decade of documented abandonment when it comes to immediate and indiscriminate access. This court requires evidence not expressions of regret.”

The judge’s ruling that day was careful and methodical. He allowed for supervised visitation under strict, court-monitored conditions. He required that both parents (my parents, to be clear) attend a family reunification program and prove steady compliance over a period of months. He required no overnight stays until progress was demonstrated. In short: the court sided with prudence. The judge made clear that he was not punishing repentance but that a child’s stability outweighed the moral vanity of late-arriving regret.

When the gavel fell, my parents sat stunned. The years had not been undone by courtroom sympathy. They were required to demonstrate a changed pattern, not simply claim it.

Outside, the press had gathered. There is a certain mercantile hunger in small-town press for scandal. They wanted to know names and angles. I gave them a quiet statement: that I sought stability for my son and wanted what was best for him, and that the court had issued a plan that made sense. The reporter looked at me as if they expected more drama. I had none to offer. The story was not about shaming but about protecting.

In the months that followed, I watched my parents in a new light. They complied, at least on paper. They attended the classes like people checking boxes. They signed the agreements and participated in supervised visits—awkward, scripted afternoons in a room with a glass wall. Sometimes my son sat at the table and smiled politely while my parents tried to rebuild trust that they had burned.

The change was slow. My mother’s voice lost its practiced polish and gained a weariness that belonged to people forced to confront themselves. My father—hardened and brittle—began to unravel in private. I never missed the way they pored over photographs like archeologists searching for an artifact that might absolve them. They wanted a quick absolution; they did not get one.

Those supervised visits were, in a way, the crucial part of the healing process. It would have been easier for them not to participate. They did, and in doing so they exposed their own remorse and their own clumsy attempts at connection. There were moments of warmth, of a shared laugh when my son told a joke that no one else quite understood. There were also moments of petrified silence, of questions the child did not want to answer. The court had been right: time was the only legitimate test for their claim.

What my parents had not recognized was that, while they were learning to be present, my son was learning to set boundaries. He had a mother who taught him to stand up for himself and to demand respect. He had friends who showed him reciprocal loyalty. He had interests: science club, chess, late-night stargazing with a battered telescope. He had a life beyond a courtroom.

There was one small, powerful moment that I will always hold. It came during a supervised visit, thirteen months after the verdict. My parents had scheduled a rare Saturday morning visit; they arrived looking anxious, as if they had misread the time. My son—older, steadier—sat quietly and then asked my parents a simple question: “Why didn’t you come when I was small?” There was a silence heavy enough to drop things into. My mother swallowed and began to speak about busy schedules, misunderstandings, pride, and the fear of public shame. She spoke in fragments, and for once she did not ask to be forgiven in the same breath. She admitted error.

My son listened. When she finished, he looked at her with the clear-eyed calm of someone who has endured and learned to distinguish between need and desire. He said, softly, “You can’t fix those years in one visit. You can start by showing up. That means being here, not by pictures and not by words, but by time.” It was not a demand so much as an instruction. He set the conditions with a maturity that astonished us both.

In the end, the courthouse wasn’t the place that solved everything. It simply stopped them from taking him by force. The harder work happened in the rooms between visits, in the therapy, in the places where hurt must be discussed and not swept under rugs. My parents learned that redemption in family is not achieved through proclamations; it is achieved through a new pattern of presence.

When the judge asked me that day, “Do they even know what you have?” he had meant “Do they understand the evidence?” But beneath the legal current was an equally human question: do they know who you are? Do they recognize the person who stepped up when they stepped aside? For a long time they hadn’t. For a long time, they had used me as a measure of their own image. But the sealed folder finally forced the mirror on their face.

My son and I, we are not vengeful. We are ordinary people living extraordinary days. There are still hard conversations—about why his mother left, about whether she will ever come back, about the pain of being abandoned even when the world says you are “lucky” to be raised by a relative. We answer those questions honestly with age-appropriate precision: there are gaps in everyone, sometimes the hardest thing is to hold space for people even when they hurt you.

Years later, when the lawsuit and all its rust had been filed away in community memory, my son and I walked along the river where he used to squat and throw pebbles. He pointed at a small stone and said, “I know where that came from—where we started.” I smiled. “And where are we going?” He looked at me, thoughtful. “Somewhere better.”

I nodded because I knew he was right. The sealed folder, the courtroom, the recorded letters—those were instruments that kept a child safe. The moment the judge asked, “Do they even know what you have?” was the moment that validated a decade of hard, anonymous work. It wasn’t about “having” in the sense of possession. It was about having the stubbornness to protect a life.

In the months and years that followed, my parents did change in ways that were messy and sometimes insufficient. They called less to complain and more to ask how to help. They sent small, tentative gifts that seemed like gestures sent across an ocean. They visited sometimes on weekends and sat through dinners without making a spectacle. My son tolerated it warily and accepted increments of contact on his terms.

Sometimes, when the house is quiet and all the dishes are done, I take out that old shoebox and run a finger across the corner of the letter that began everything. It is frayed now, softer and worn by the years, the ink fading slightly. The words in it are still jarring, but they are also proof that sometimes people who are pushed to the edge will choose the only option that promises protection. They are proof that family is not the people who leave you; family is who stays.

When I walked out of court with my son that last time, he slipped his hand into mine and we went home. The judge’s question had been a doorway into truth. I had nodded because the truth required it. We had a life, complicated and ordinary, anchored in the quiet work of showing up. The sealed folder had done more than reveal evidence. It had reminded everyone in a small room that actions speak louder than declarations and that love can be defined by endurance and the daily acts of care.

That is the ending, in my mind—the kind that is not cinematic but real: a continuity of small days, a slow repair, a boy who learns that protection can be fierce and kind, a woman who finds once again that raising a child is not a burden but the most clarifying of callings. The sealed folder sits in a safe now, not because it is a trophy, but because it is a record of what choices protected a life.

And when people ask me if I regret anything, I tell them the truth: I regret nothing that kept my son safe. I have a neat, unembellished life now: casseroles brought by good neighbors, soccer games where we cheer for him, a bedtime ritual of reading and laughter. It is not glamorous. It is the life we chose, stitched out of loyalty and small, daily courage. The court echoed a single sentence that day: family is who stays. We stayed.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Steve Doocy surprised viewers by declaring his return as a regular Fox News host, but this time with a brand-new show: “This is what they owed me.” – Unlock the secret in the comments

Where is ‘Fox & Friends’ Co-Host Steve Doocy? Steve Doocy’s Transition: What Happened to the Fox & Friends…

SH0CKING NEWS: Tyrus DEMANDS NFL CANCEL Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl Halftime Show

Tyrus exploded over the NFL’s shocking decision, calling it nothing more than “a political stunt designed to smear patriots and…

BREAKING RISE: JAMIE LISSOW GOES FROM LATE-NIGHT SIDEKICK TO COMEDY’S NEXT BIG STAR — AFTER ONE CHANCE ENCOUNTER THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING.

Nobody saw it coming. Jamie Lissow was the funny guy on the couch, the late-night guest you laughed with and…

Stephen Miller and his wife are overjoyed to announce the birth of their beautiful daughter, Mackenzie Jay Miller. Her middle name was chosen in honor of a member of the Miller family, carrying a deep sense of connection that Stephen holds especially dear.

Stephen Miller Welcomes Daughter Mackenzie Jay Miller: A Name Rooted in Family Legacy In a heartfelt announcement that has…

Jessica Dean broke down in tears, admitting defeat in the brutal weekend ratings battle between CNN and Fox News.

As the veteran anchor faced CNN’s internal reckoning for repeatedly failing to deliver on promises of gaining the upper hand,…

I raised my nephew as my own son because my sister didn’t want him, now her daughter is… CH2

I raised my nephew as my own son because my sister didn’t want him, now her daughter is jealous of…

End of content

No more pages to load