My Sister Arrested Me At Family Dinner—Then Her Captain Saluted Me “General, We’re Here”

Part One

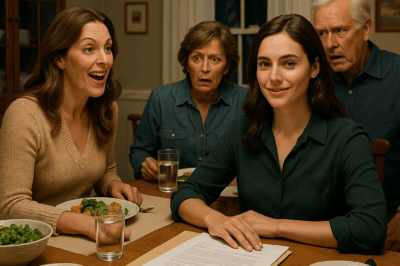

The chandeliers burned like captured stars over the Mitchell family table. China chimed. The clink of cutlery threaded through laughter. Velvet gowns and tuxedos created a tide of gloss and carefully curated warmth. This was the Mitchell charity dinner—one part family theater, one part social obligation, a ritual of smiles and successful faces that let the city believe the Mitchells were as generous as they were wealthy.

Clara stood at the head of the table like a queen reigning over her kingdom. She had that practiced parlor voice all polished and ready, the kind that could make any sting sound like a compliment. For years she’d been flawless at this. Years of Blond Ambition and charm school had taught her every tilt of expression that read generosity while draining an account.

I watched her move through the crowd, the perfect hostess, tossing a laugh like a ribbon. People adored her. They bought into her curated life the way they bought into charity causes—rarely asking where the money really came from, preferring the illusion to the mundane truth.

I sat at the table a little off to the side, my own dress muted on purpose, my badge stashed beneath the hollow of my collarbone. A faint shimmer of metal pressed against my sternum when I breathed: it was a law enforcement badge, not a family heirloom. I tacked my attention to the speech she was about to give with the same benign interest I gave to many of her events. It was, in part, the perfect stage for her.

She began, gracious and luminous, thanking donors with the practiced warmth of someone who’d spent a lifetime learning applause. People threw their hands up to their glasses, toasts lifted. A microphone caught the rustle of silk and moved it into the ears of a room full of good intentions.

Then Clara’s voice sliced through the applause—not through the microphone, but in my direct line of sight, a brand of cruelty she never bothered to hide with velvet. She pointed at me with the kind of triumph only someone who had hoarded years of petty cruelty could wear properly.

“You’re under arrest for impersonating a federal officer,” she said, loud and lucid and certain, as if she had rehearsed the line like a joke for an audience that never questioned her authority.

The room froze as though the song of the evening had been cut mid-note. A few glasses trembled in the light. Phones raised. People bent forward, curiosity sharpened into spectacle. Her words hung there, delicious and precise. She believed, in that moment, she had destroyed me.

There are a few varieties of silence. The one that fell after her declaration was the public kind: a silence that waits for a scandal to bloom. Dozens of eyes turned to me. I felt the cold slide of judgment and amusement and the delighted cruelty of people who like to watch a ladder kicked away from someone climbing.

Clara smiled, a small, tight thing that had cost her effort to arrange. She saw every head turned and read the story they expected: her, the graceful matron; me, the impostor caught. That image had served her well for years.

What she didn’t see was how close she had come to underestimating me. She never had the patience for the slow patient work of building an identity in the way men with power do—through meticulous hours of study and practice. She destroyed; I built.

I stood. The badge under my dress pressed colder against my ribs and, for a heartbeat, I let the room think I would cower. I had been invited to this gala—two reasons: to confront her privately with the last of the financial records that tied her to Robert’s missing millions, and because the Mitchells always loved a spectacle. But she had chosen to create her own spectacle first.

“Clara,” I said, loud enough to thread the air. “I’m glad you decided to make this public. It will make things much easier.” My voice had the soft evenness I used when leading investigations; officers used it to calm or to command. The microphone caught it and the room leaned in.

She laughed—the high, practiced laugh that had closed many arguments in our family. “Marissa, is this some kind of joke? Is this one of your stunts?” Her fingers curled into the stem of a wine glass, knuckles whitening. Her smile quivered.

I put my hand under my dress, pressed my fingers to the badge through fabric. I’d spent years making sure it was not merely metal and an ID number, but a ledger of integrity. I had signed affidavits with my blood and my oath. I had led raids and had gone undercover in offices far worse than the perfumed air of a charitable gala. My career had been carved with a tempering process I didn’t bother to show to people who thought appearances were the whole of truth.

“Call your husband,” I said. “Ask him if he knows where ten million dollars of his company’s money went. Ask him why there’s a shell company in the Caymans that carries his signatures, and why large transfers left his accounts that he can’t explain.”

If Clara blinked, I had missed it. Her face tightened.

“You’re out of your depth, Marissa.” Her tone tried to be condescending but it landed hollow.

There was a rustle at the far end of the room as two men in plain suits who’d been mingling near the buffet stood up and straightened. They weren’t the type who belonged at charity luncheons looking for plaques; they were the type who arrive at scenes with a purpose, who spoke in clipped sentences, who had one hand usually on a notebook or on a badge. I had arranged for them; I’d whispered to them that tonight I would not be alone. Months of work had led to this precise choreography.

“They’re with me,” I said simply, and then I pulled the badge out, exposed the star to the room in a motion that felt old and right, like drawing a blade in a crowded square to test the wind.

Something in the air shifted. The watchers’ delight curdled into interest. The men moved forward and did what professionals do: they kept their eyes level, hands relaxed but certain.

“You’re under arrest,” I heard Clara say then, the words like spit. She tried to recover with a moralistic flourish. “For posing as an officer, for tricking good people—using your charm—”

No. I didn’t need to stage a counterattack of words. The evidence did the work for me. Evidence is an acid that dissolves all performances. Wire transfers are not opinions. Shell corporations do not have facial expressions. Forensic accountants do not tell stories; they trace numbers. The screen at the back of the room flickered to life because I wanted it alive, and a roll of images began to scroll for the guests like a silent, terrible film: bank records, ledger entries, signatures, invoices from phony vendors, photos of nocturnal meetings in hotel lobbies.

I had seen Clara’s empire from within. She had thought her web of lies was clever, a pattern of small thefts and cunning rationalizations that added up to a fortune. She had tried to dress her greed as need and her thefts as entrepreneurial risk. She had become practiced in the language of deception.

“Marissa, she’s my sister,” Clara squealed, clutching for a refuge that the room could not now give. There’s a certain cadence to how gaslighting sounds when it’s trying to convince a crowd: a performance in which familial labels are used as shields. She had used them for years to blunt accountability.

“Sister or not,” I said. “These are the facts.”

When the agents moved in, Clara’s composure cracked. It happened quickly—her hands flayed, pearls like wounded birds, the wine glass shattered on the floor, and then the crisp click of cuffs. She screamed about being framed, about jealousy, about me being unhinged. The cameras loved her for a time; guests whispered, phones recorded, the city’s social feeds began to hum. I watched Clara dragged past me, her hair a mess of splendor and disgrace.

As she passed, her lips brushed my ear with a parting curse: You’ll never be a Mitchell. The phrase landed like something meant to bruise. The Mitchell name had once been her fortress. She thought disinheritance was a fate worse than exposure. She had never considered that integrity might be a larger inheritance.

Later, in the flaring white lights of the media scrum outside the ballroom entrance, I felt the gaze of a thousand strangers on me. Questions volleyed in a chorus. Had I acted out of vendetta? Was this personal? Did I know Robert Mitchell? The truth slid forward, carefully: I had been the case agent on the investigation that led to charges; I had been collecting the evidence that made the arrest possible. I had not stage-managed Clara’s meltdown; she had staged hers by announcing my supposed impersonation.

Afterwards, alone in my car, the badge heavy against the soft fabric of my blouse, I let my breath come back. For a long moment I sat and let the city lights blur into streaks; the fight that had filled my chest with years of tiredness and furious energy slid out of my shoulders.

People tell stories about revenge with the soft cadence of myth, as if avenging crossed wrongs were a single bright, satisfying point. They do not talk enough about the slow accumulation of hours—the boring, meticulous work of sifting bank statements, of conducting interviews, of drafting affidavits and court-ready exhibits. Revenge that matters is never just a shout in a ballroom. It’s a ledger and a lock on a drawer and a signature. It is patience sculpted into an outcome.

Clara’s arrest was not titillation. It was consequence. Yet even in the aftermath, consequence tastes like ash if the work doesn’t end with something salvaged. I had not wanted to watch my family—the small, messy part of it—burn. What I wanted was exposure, accountability, and for once, for me to be allowed to stand in the light without being whispered into the dark corners of the room.

That night I went back to my tiny apartment. I changed out of the borrowed dress into a uniform I kept for no reason anyone could understand except me. The uniform remembered me: the way it sat on my shoulders, the crisp lines, the way the fabric made my back straight. I paused before the mirror. I had not been born into a life like this; I had been built into it with choices and training. I was not just a woman who had been slighted; I was an officer who had entire logs of investigation stored in secure servers.

My phone buzzed—messages that read, in various tones, congratulations, accusations, curiosity. My mother texted: You’re too harsh, honey. My father sent a single succinct line: Be careful. Even now the old scripts tried to rewrite the narrative. Family, when threatened, will write you into the parts that keep them safe, not the parts that demand they be better.

There was one more message that made my heart twist: an image sent over an encrypted channel from the task force captain. It was a photo of a tiny keypad screen, the caption: We’re in position. Are you ready? The note was signed with the crispness of someone who’d learned how to say nothing and still say everything—Captain Elias Voss.

I had worked hard to stay unspectacular. Leadership had taught me how to hide a plan behind a polite demeanor. But now the plan moved forward.

Clara’s arrest made the news tomorrow in the way small scandals do: first a shock, then the appetite for gossip, then the heavier work of charges and arraignments. Her husband—Robert—sat in interviews with the pale, polite outrage of a man who had not noticed his money being siphoned until the numbers became impossible to ignore. He had been betrayed by his wife’s appetite for excess and secrecy. The press consumed the story and sent a hundred different narratives out into the city.

Within days a judge issued an indictment on several counts: embezzlement, fraud, money laundering. The evidence I had stood up in the ballroom and brandished became the backbone of the prosecution. I participated in the court filings and in a small handful of preliminary hearings; the law moved like an animal that was deliberate rather than quick.

Family responses were, predictably, messy. My parents called once, a trembling sort of interrogation disguised as concern. “Did you have to humiliate her?” my mother asked. “Do you realize what this will do to the rest of us?” Years of protecting the family brand flooded their words.

“Yes,” I answered, and the single word felt like both shield and blade. “I have to stand for the truth.” There will be those who call it vengeance. There will be those who call it justice. Both are often the same thing, depending on how one frames the story.

Through it all, a quiet current of pride persisted in a place I rarely let myself go. On the day Clara was arraigned, I sat quietly in a bench, the courtroom’s dull light and the air conditioning doing the work of sobering everyone. She glared at me like an animal caught without its den. For a moment I thought she might reach for me and let rage be intimate and electric.

She did not. She kissed her fingers and smeared them in a public display, a gesture meant to suggest being above the fray. It read to me like petty indulgence.

My task force, the team of people I had built this case with, sent me a photograph afterwards—standing beneath the courthouse steps, tired, in suits, a mix of ages and faces that had become my second family. Captain Voss was there; his salute was private, but he said, loud enough for the nearest reporters, “We’re here for the hard parts,” which was his way of saying that the work did not end with a spectacle. It ended with discovery, with due process, and—if justice allowed it—some measure of reform.

The arrest had been a climatic note, but Part One of this story—the arrival of exposure—was only the prelude. I had thought that once the badge had shown and the cuff had clicked, the echo would die down and the world would proceed. But life proves stubborn. It insists on speaking back, on testing whether revelations bring about change or merely rearrange the same small insecurities into new spectacles.

The press called me “the vengeful sister” or “Glitter’s nemesis,” but mostly they stared as if waiting for some collapse, some scandal, some moment where a hero had to fall. I wanted to make sure that didn’t happen. I had not labored against Clara just to replace one public lie with another. I had done what I had to do to reveal her fraud and to bring an end to a cycle that had once stolen my future.

That night, back in the quiet of my apartment, Captain Voss’s message sat on my screen with something else attached: a short note, clean and direct—Eli: General—are you ready to finish this? I stared at the typed message for a long time.

Part One ended not with a declaration but with a preparation. The battle had been joined in public, but the legal fight, the inquiry into Robert’s accounts, the extraditions, the calls to offshore banks—all those things—were a long, meticulous matter. Clara’s arrest was the first necessary fracture. The captain’s note hinted at a plan larger than my private revenge, a mobilization of people who spoke the language of law rather than of gossip.

When you take off a mask, the person behind it may fall, or may scramble, but the world you have cut into will not always change overnight. You have to keep cutting until the rule of law can hold the gap. I was ready to keep cutting.

Part Two

In the weeks after the ballroom, the Mitchell household felt like a house with all the windows open—voices moved through it that had not before. People who had invested in Clara’s charities for twelve years suddenly found themselves rubbing their temples, asking what audits they had missed. The social world that had waltzed around Clara’s persona learned to speak with hedged curiosity, and for a while, everyone watched and waited for the next turn in the saga.

The legal process is not a cinematic strand. It is methodical and grueling. My task force prepared for it the way surgeons prepare for a complex operation: long, precise, and with an eye for the possible complications. Clara’s lawyers filed motions to dismiss, claiming my motives were personal. The defense argued that financial records could be interpreted in various ways; they said trusting one another in marriage was part of what Robert expected.

Robert, for his part, was a complicated figure. He had been measured and silent in public, but in private interviews with investigators his voice had that small tremor of a man who had not expected betrayal from the person he loved. Betrayal in corporate settings is not always an affair of passion; sometimes it is a matter of accounting, a matter of sophisticated, dull, and repetitive theft that gets hidden behind invoices and the polite language of “consulting fees.”

The big push in our case was the forensic tracing—following the money. We marshaled accountants, subpoenaed bank logs, presented paper trails that couldn’t be buried in charm. Each evidence packet we sent to the prosecutor felt like a bracing step closer to finality. We were not trying to ruin a life for spectacle. We were aiming to undo a pattern that had been normalized—where the optics of charity hid the behaviors of theft.

My parents’ reactions were complicated. They loved Clara in a way parents do—habitually, fiercely, and through a fog of denial. Confronting the idea that they had been complicit at times required an admission that they had been wrong about the child they’d invested in. That is the kind of grief that moves slowly.

After Maple Day—the day the media hung their story, the day they called my phone to ask how it felt—I visited my father. He was silent and small, the way old men go when they are suddenly aware of their own mortality and misjudgments. “We raised them both,” he said quietly. “But I was proud when you wanted stability… God, I never…”

“You shielded them,” I responded. The word landed like a blunt instrument. “You and Mom protected her charm. You didn’t want to see the work she was doing to the world.”

He closed his eyes. “I wish I had seen it sooner.” He said it like a prayer but with less forgiveness—he knew too that apologies had a halting currency.

Clara’s first court appearance was a storm. She arrived swathed in a predictably expensive coat, the kind that declared it could be washed but never would. Cameras crowded the vestibule like persistent birds. She stood before the judge and read a statement about being misunderstood, about helping charities, about being a wife who loved her husband and never meant harm.

The judge read the charges with a grave voice. Then the bail hearing came and we proceeded through the motions that the law considers appropriate. Bail was set. The defense argued that she posed no flight risk. The prosecution argued that the pattern of transfers suggested deliberate planning. In the middle of all this, I sat in the gallery and watched the woman who had taken my scholarship for college speak aloud the very words that had once been enough to open doors for her: “I was only trying to keep up,” she said.

The trial began three months later. Months of depositions, investigation, and negotiation had compressed into a finite, legal drama. There are moments in trials when the noise of the outside world fades and all that exists are facts offered one by one—numbers with dates, time-stamped emails, travel records. The magic of a courtroom is that it converts rumor into traceable, documentable sequence. It makes speculation sober.

We presented an accountant who walked through an intricate path of transfers like a conductor teasing out a melody. Offshore accounts, shell companies with names not easily associated with any person, phantom consultants who had received six-figure payments—all of these were laid bare. When the defense cross-examined the accountant, they tried to imply alternative explanations—business ventures that did not succeed, errors in bookkeeping, even transactions that might relate to Robert’s other businesses.

It was then that we used the human records: testimony from vendors who had been paid for services they did not provide, witnesses who testified to being paid for ghost work. These accounts punctured the defense’s arguments that mistakes or poor bookkeeping had been at play. The pattern read like a manual—calculated, repeated, and persistent.

Clara’s pleas varied. At times she insisted it was all a misunderstanding; at times she blamed me. She tried to weaponize our familial history, painting me as a woman who sought revenge. The defense counsel’s game was to create doubt—always a defense attorney’s job—but the facts had a weight that creates gravity. When you pile enough corroborated testimony atop financial evidence, the chance for reasonable doubt narrows.

During a lunch break in the early days of the trial, I walked the courthouse steps and saw Captain Voss standing with a small group of men and women I had come to respect and rely upon. He crossed the grit and, in one crisp movement, came to attention and saluted. The gesture felt archaic and sudden and entirely right. The words he said, meant more for my private room than for the court’s dazzle, were, “General, we’re here.”

Something older than my badge rose up at the sound of that title. Years before any cases or courtrooms, I had accepted a commission in the reserves; austerely, sparely, I had learned how to lead and how to be led. The training taught me an economy of authority—that hierarchy is not meant to puff you up but to coordinate the efforts of many.

“Call me Marissa,” I told Voss after the salute. “You know I don’t parade rank.”

“You earned the tongue both ways,” he said dryly. He walked me to the side and we spoke in the curt voice of people who share long lists of tasks. He was precise: witnesses had been intimidated; there had been threats against me online; the press sought to make the story personal. He laid out how his people would manage security, how the team would escort witnesses in and out, and how the task force would support the prosecution.

We were not cheerleaders of spectacle. We were the careful ones who cleaned up after spectacle. Our presence kept the process intact enough that the law could do its work without deliberate sabotage.

The trial stretched. It was laborious, heavy, and sometimes surreal—Clara’s teary-eyed dramatic speeches one day, the quiet presentation of bank transfers the next. The jury listened with a mix of pity and anger. Witnesses swore under oath. My mother sat in the gallery with her hands folded like a woman practicing contrition; she was not yet contrite, but she was present and that mattered.

In the end, the jury’s deliberations did not take as long as the morning papers suggested. The patterns were visible to a careful mind, the numbers precise and the testimonies consistent. Guilty on most counts. The sentence would be determined later, but the verdict itself was a kind of closure to a chapter that had, for too long, been anonymous.

After the reading of the verdict, the room emptied into a different city of air. Cameras flashed, but it was not the same fever as the arrest. This was a quieter consummation: a man who had been stripped of status and a woman who had once believed she could buy away consequence. I stood after the verdict like someone who had been carrying a weight and had finally found a place to set it down.

The family fractured in public ways. People who once drank at the same table stopped returning calls. Clara’s friends distanced themselves; they had no appetite for criminal association. Robert released a statement of deep sadness and a vow to recoup losses. My parents were quiet but, gradually, present in different ways. There was no celebration, only a long, exhausted exhale.

In the months after the trial, some things began to weave themselves into new shapes. My mother called me once and asked if I would come over. I said I would be there in an hour.

The house smelled like old bread and perfume. Her voice trembled when she invited me into the kitchen where the light slanted across the counter in a way that revealed dust. There were no tokens of the charity’s public face: no plaques, no ribbons, nothing to show. My mother met me holding an envelope.

“It’s from your college,” she said. “I finally looked at the letters you had applied with.” She had found a box of my old applications when she cleared out one of Clara’s old suitcases. There were essays folded and smudged with ink, merit letters, and—strewn among them—one letter that had never been opened. “We never—” she began and then stopped. She would later not remember which words of apology mattered and which were only a habit of speech.

I sat with my mother in the kitchen, not as an officer, not as a woman who had won a case, but as a daughter. She told me that they had been ashamed and scared, that they had chosen the path easier than the right one, and the cost had been not only my scholarship but their integrity.

I said I forgave them. It was not that simple. But I forgave because if I did not, the bitterness would curdle further. Forgiveness, I had learned, is often less about absolving another and more about declining to be imprisoned by what they have done. We arranged therapy appointments. We began to set rules for family finance—no more secret accounts, transparency, and counseling for our relationships. These practical measures were tedious and, to me, as important as any courtroom victory.

Clara took a harsher path. The court sentenced her to a term that included restitution. Prison does terrible things to people’s egos. Some people re-emerge from it transformed in ways that make them kinder; others simmer with resentful intent. Clara would exist outside the family circle but not entirely out of its shadow. She appealed, of course; appeals are a long legal cough that never fully goes away. Ultimately, she served time and then came out smaller, stripped of social pretense.

There is a strange reverence people attribute to the finality of sentences, as if they quietly repair a collective social ledger. But repair is not a courthouse’s purview. Repair belongs in living rooms, in the messy work of saying sorry and meaning it. We began that work, messy and halting.

What surprised me most was how little joy I felt in Clara’s collapse. I had wanted justice. I had needed accountability. But I had not wanted to become someone who built a life out of another’s ruin. The feeling that rose after the verdict was not triumph but a slow quiet relief. The truth has a heavy taste, and the recovery from it is a long and practical affair.

There were other things to do. Robert sued for civil damages; some of the money had been recouped and placed in restitution. The charities Clara had run fell into temporary disrepair—people donated, unsure whether the money would be used well. We worked with auditors to ensure those funds were reallocated properly. Part of my desire had not been revenge but repair: to make sure that the patients, the programs, and the good work funded by others were not left without resources because a woman had taken advantage.

On a smaller scale, I took time to call and meet with younger women in the force. They wanted to know about my path—about the scholarship I had lost, about the way I had built a career not as revenge but as a way of making sure I had a seat at the table. I told them what I could. Leadership, I told them, is not propped up by titles alone. Leadership is a series of small choices: to be methodical, to carry evidence with respect, and to ensure that the law is a tool for truth.

Months after the trial, one crisp morning at the barracks, Captain Voss walked into my office and, in front of everyone who had come to know him as a man of little nonsense, he saluted. It was an old instinct, a courtesy from the military life I had embraced and kept. “General, we’re here,” he said with a roguish smile that betrayed that this was not a ceremony but a recognition.

I laughed first out of surprise—no one had called me that in years—but then I took his hand and let the moment be one of small comfort. Ranking or not, we had the privilege of a task we took seriously. That salute was not the end of my story; it was an acknowledgment that the work of law and service is embodied by many people who show up day after day.

In the quiet aftermath, family dinners returned to something less theatrical. We ate with less pretense. My mother learned to ask instead of assuming; my father learned to sit and listen rather than fix. Quinn came to my office one afternoon and slid a folder across my desk—his accounting of what he had done, his debts, and a list of scheduled payments. He looked small then and open, the best shape a man can take when he really wants to be better.

“Thank you,” I said. He nodded, and then left, not for the casinos but for a bookkeeping class he had enrolled in. Little changes multiply into a life.

Clara’s story remained public for a long time in the way social memory keeps the story of a once-shining thing fallen. People talked about the gala in years to come like a moral anecdote: about appearances and about the way truth finds a way when someone keeps an eye on the ledgers. I did not relish that fame. I prefer the quiet labor of documentation and accountability, of showing up at hearings and making sure the small, overlooked things are done properly.

When the dust settled sufficiently that I could breathe without the press at the gate, I walked back to the little campus where, as a teenager, I had once opened an envelope promising a scholarship. The bench where I had once sat and cried over lost courage now sat under a tree with a new plaque: To those who keep watch, in gratitude. It felt like both irony and healing to stand there.

A few friends and task force members—lingering colleagues who understood the thousands of tiny choices that make a life—joined me. Captain Voss raised his coffee cup and gave me a toast in low, steady tones. The salute then was private. “We’re here,” he said, and I felt the truth of it.

In the end, the story was not about the arrest at a chair-lifting gala or the drama of a cuff. It was about a lifetime of choices: my decision to build a life of service, the slow administration of justice, and the messy, stubborn work of making a family admit they have been wrong and choose to do better.

Clara’s empire of illusion fell away. My family’s illusions cracked. Some mendings were stitches that will show; some are new fabrics sewn altogether. I carry my badge still. I carry my scars. I carry the memory of a scholarship lost and the taste of what it felt like to be overlooked. But I also carry the quiet satisfaction of a ledger properly closed, of evidence honored, of a system that worked when people did the work despite the applause or its absence.

The last scene in the story was not a curtain call. It was a small family dinner—no charity balloons, no cameras, just food on a table, a mother who had learned how to ask for help, a father who put away the golf trophies, and a sister who is learning to live with less and be accountable for more. The captain’s salute stayed with me like an old song. “General, we’re here,” he had said, and in the way a life arranges itself, that presence was precisely what had mattered: a team to watch your back, a country to serve, and a family—fractured but, finally, learning to listen.

Justice was not the triumph I had imagined in high-dramatic terms. It was a long, weary, right thing. Clara went to prison and paid restitution; the charities were restored; my parents sought therapy; Quinn learned to manage his impulses. I went back to work. I answered the next call when duty came. The badge around my neck was not a weapon for revenge, but a reminder: that some debts have to be paid not with money but with truth, and when truth is brought forward, it is the law, not the spectacle, that must finish the sentence.

When the Captain saluted me—General, we’re here—it was not flattery. It was a promise that the work would continue, that a small army of ordinary people would see the rules enforced. And that knowledge—that people would show up and be faithful to their roles—gave me back something I’d thought lost: faith in institutions when they are honest, and faith in myself when I chose to stand in that honesty.

There are dinners in life that mark turning points. That night in the ballroom could have been just another footnote. Instead, it became a mirror. We finally had to look into it, and that is the most dangerous and the most honest thing a family can do.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

At a Family Dinner, My Sister Announced She Was Moving in—Too Bad the House Wasn’t Mine Anymore. CH2

At a Family Dinner, My Sister Announced She Was Moving in—Too Bad the House Wasn’t Mine Anymore Part One…

My Parents Gave My Sister a BMW with a Red Bow. I Got $2. So I Left and Blocked Them at 2AM. CH2

My Parents Gave My Sister a BMW with a Red Bow. I Got $2. A plastic piggy bank. Two dollars….

Grandpa Spent $59K On A Family Trip—Then Mom Left Him At The Airport. I Gave Up My Seat… She Slapped. CH2

When Grandpa generously spent $59,000 to take the entire family on a luxurious vacation, everyone smiled—until the trip ended. At…

My Sister Got Me Fired, Then My Family Demanded Money When I Found Success. What They Got Instead… CH2

My Sister Got Me Fired, Then My Family Demanded Money When I Found Success. What They Got Instead… Part…

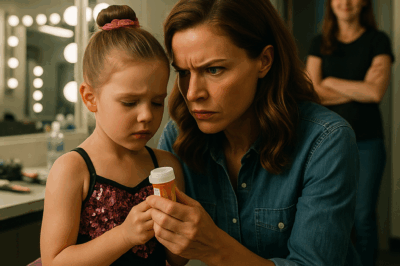

Sister Swapped My Daughter’s Medication Before Her Recital to “Teach Her Humility” CH2

Sister Swapped My Daughter’s Medication Before Her Recital to “Teach Her Humility” Part One The moment your child collapses…

My Husband Slipped Sleeping Pills in My Tea—When I Pretended to Sleep, What I Saw Next Shook Me. CH2

My Husband Slipped Sleeping Pills in My Tea—When I Pretended to Sleep, What I Saw Next Shook Me Part…

End of content

No more pages to load