My Scheming In-Laws Exposed My “Affairs” At Family Dinner — Then Froze When I Revealed…

Part One

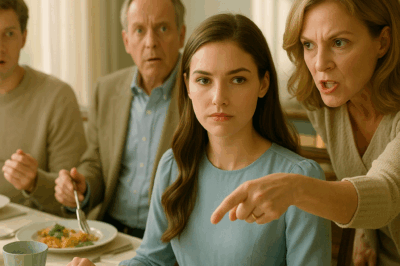

The first photograph landed on the mahogany like a verdict.

A crystal chandelier hummed above the table, silver reflecting its light in precise little stars, the roast still steaming, wine sweating on stems. In the glossy snapshot, I sat at a small table in a cafe—chin tipped toward a graying man in a navy suit, my hand resting casually on my glass. The second photo slid after it: the same me, different restaurant, different man. The third, then fourth, like playing cards. With each one, the room grew quieter, oxygen thinning into a vacuum.

“Look at these,” Amanda said, her voice syruped with concern that didn’t make it to her eyes. She turned them outward, to the crowd. “While David is working himself to exhaustion, Sophie has been running around town with other men.”

She placed her manicured hand on my husband’s shoulder as if offering him sanctuary. Across from her, Jessica—his mistress, in a pale dress that wanted to disappear and be seen at the same time—kept her eyes on the tablecloth. On David’s other side, Eleanor, my mother-in-law, lifted a shaking photo and pressed her lips together in a slit of betrayal.

Amanda was radiant in an awful way, the stage manager of this scene she’d been dying to direct. “Now,” she delivered, pivoting to face the table like someone unveiling a new kitchen on a home show, “you don’t have to feel guilty about Jessica. And you definitely don’t have to give Sophie anything in the divorce.”

My name is Sophie Bennett. I was thirty-two and my hands were steady when I set down my fork.

“Nice pictures,” I said. “Good lighting. You must have paid your private investigator quite a lot.”

The triumph on Amanda’s face stuttered. She’d budgeted for tears, maybe an implosion, the wet drama of someone who still thought love was a reward you could snatch before your sister-in-law did. She hadn’t planned for composure.

“That’s all you have to say?” she snapped, performance wobbling. “You’re not even going to deny it?”

I reached into my purse. The collective inhale from the Harringtons—the way their shoulders went up together like a pack—might have been funny at any other table. Instead of Kleenex, I took out my tablet and set it in front of me. The black screen threw back a dim reflection of my face.

“Deny what?” I asked mildly. “That I’ve been meeting men? Correct. Those men are divorce lawyers.”

The silence that followed had a geography. You could feel people navigating it: the search for a script, the way eyes flick to leaders. David looked down at his water glass as if the answer might be floating there.

I tapped my screen and a gallery loaded. I swiped and photos of the same men appeared, this time in professional headshots on their firms’ websites. “This is James Morrison,” I said, tapping the photo of the first man. “He’s the best family lawyer in the city.” Swipe. “Michael Turner. His firm specializes in cases involving infidelity.” Swipe. “William Parker. He’s excellent with fraudulent transfers. Teaches continuing education courses on finding assets buried under shell companies.”

Amanda’s face went through a rapid series of micro expressions—denial, confusion, the beginning of a thought I saw land in her eyes like a bird that meant to land somewhere else.

“You see,” I continued, turning to my husband of eight years, “when I discovered David and Jessica three months ago, I decided to prepare properly.”

“You’re lying,” Amanda said, but the word came out smaller than she intended.

I opened my email and enlarged a PDF. “The wonderful thing about legal consultations is there’s always documentation.”

If you’d asked me a year earlier how I’d react to learning my husband had found a lover, I’d have described something messy: yelling in the driveway, tears into the crook of my arm, a suitcase shoved into the back of a rideshare. I did all of those things in one way or another—but not at first. The first thing I did was pour tea. Then I opened my laptop.

I didn’t drink the tea.

For three months I learned a new language: valuation caps, discovery requests, retitling, constructive trust. I sat with James and Michael and William in rooms with soft leather chairs and Kleenex boxes that sat on end tables like props, and I watched their faces as I asked different versions of the same question: How do I leave a man who thinks I won’t? How do I survive my husband’s family?

The photos Amanda had laid out were bait I’d set in public places. Because Amanda, as it turned out, had a habit of subtracting privacy for sport. She had hired a P.I. with the same stealth she brought to whispering to waitstaff about dietary restrictions. She sent him after me like a dog after a duck and he fetched exactly what I wanted her to see.

When you’ve been underestimated long enough, the smallest acknowledgments—like a good light on a staged photograph—become a kind of private joke.

Now I swiped to a spreadsheet and took a breath I didn’t need. “But the consultations aren’t the interesting part, are they?” I said, eyes on the person whose opinion used to own me. “Do you know what else I learned, Eleanor?”

Her knuckles whitened against the tablecloth. “What do you mean?”

“I learned that three months ago—precisely when David acquired a sudden interest in Pilates studios—someone began moving assets. A holding company formed out of thin air to own two rental properties. A family trust created, ‘for estate planning purposes,’ with only one beneficiary’s name on file. Liquid securities transferred from a joint account missing one signature that clearly should have been there.”

“Routine business.” George—my father-in-law, whose voice always tried to pass itself off as authority—recovered first. “Sophisticated families plan ahead.”

“Sure,” I said. “And sophisticated families also know that fraudulent conveyance statutes don’t care how sophisticated you are. Nor does the judge when your daughter-in-law brings a timeline and a forensic accountant.”

I turned the screen toward David. “Did you read what you signed?”

His brows knit. “My father said—”

“Your father said it was routine,” I finished for him. I let him recognize the truth he wouldn’t speak: his father had put him in the path of a crime and told him it was a sidewalk.

“We were protecting you,” Eleanor tried again, voice cracking like porcelain in heat. “We welcomed you into our family and you—”

“No,” I said gently. “You welcomed me into a role. A role that made you comfortable.”

Amanda’s mouth wanted to argue but hadn’t found the words. “But—but those photos,” she stammered, groping for the thing she still believed would save her. “You were touching them—your hand—people saw—”

“They were in public places,” I said, smiling thinly. “You were meant to see them.”

This was the part no one likes to talk about when women get sharp: how anger gets metabolized into discipline. I felt something like mercy for all of them. Their trap had been obvious. Mine had been precise.

I stood, smoothing my dress, slid my tablet back into my purse. “Oh—and David?” I added at the doorway. “Your lawyer will receive the paperwork tomorrow morning. You might want to read it carefully, especially the section about fraud. Judges get prickly when people try to make their jobs cute.”

At the vestibule, I paused and looked back at the brunette perched quietly at the edge of the table. Jessica. The woman who wore my husband’s secrets like a sweater in July. She kept her gaze on the table runner, knuckles white. She had texted me the week after the first day I sat across from William Parker, because women know the shape of each other’s fear.

He says you’re crazy. He says you’ll get nothing. He says you never worked. He laughs.

It hadn’t taken me long to show her screenshots of David’s messages to a third woman, archived in a folder labeled Pending, as if he was negotiating an acquisition. It doesn’t take much for the veil to lift when the veil is already threadbare.

“Thanks for the photos, Amanda,” I said politely. “They’ll make excellent evidence.”

Outside, the evening air felt like a clean shirt. In the car, I finally let the smallest smile settle at the corner of my mouth, the one Jessica had said made me look like I knew the endings to things before they started.

—

Two days later, James Morrison’s conference room was both warmer and colder than the Harrington dining room. Warmer in the way that money buys carpet you can’t feel through your shoes; colder in the way it echoes when emotion is the only thing left to fall.

James led, because that’s what James is paid for. He assembled the timeline like a case study: harassment of a marital partner, fraudulent transfers, intention to evade equitable distribution. He didn’t raise his voice because volume is a poor substitute for fact. Beside him, William Parker stacked exhibits the way a mason stacks stones. Michael Turner—who has a sense of humor somewhere under his tie—whispered the occasional translation for the parts only lawyers love.

David came in with a lawyer who tried to outbluff a docket and discovered the docket had no sense of humor. Eleanor’s tissue crumpled five times before her ring hit the table with a soft clink that sounded like it meant something. George looked like someone had explained physics to him and he still believed he could talk gravity into a corner and win.

Amanda trailed behind them, trying to reorganize her performance into a protection; she kept her shoulders back and her chin up because she’d been taught posture can do what character won’t.

“Here’s the thing,” James said at one point, after we had pulled apart their sequence of transfers like a sweater from a discount bin. He has a way of making clearly sound like a comma. “You can make this very public and very complicated—or you can sign the agreements Sophie brought today and go home having learned a very expensive lesson.”

David’s lawyer asked for a minute. They huddled at the far end of the table, murmuring in a noise that sounded like regret being spun into strategy and failing to stitch.

“Fair terms,” the lawyer returned at last, his eyes dull. “We’ll sign.”

Eleanor drew breath to argue. George placed a hand on her forearm. “Sign it, David.”

Before anyone could reach for a pen, Amanda tried to throw herself a rope. “She flaunted those meetings,” she said, turning to me as if scolding would restore her old magic. “You liked being seen. Admit it.”

I laughed then, softly and without joy. “Your P.I. posed no threat to me,” I said. “He was working both sides. He makes more money with me.”

The look on her face—betrayal of her own design—was almost too human to watch. It’s intolerable when the mirror you’ve polished for years shows you something that won’t be obedient.

We signed. James traded the folders for copies. His assistant brought in cold water none of us wanted. The clock marked passing time reluctantly.

As we rose, David said my name in a way that made me remember his voice the first time he’d said it over Chinese takeout on a floor that still smelled like paint. “When did you get so calculating?” he asked, and the word came out like he’d found it in a drawer that didn’t belong to him and wanted to put it back.

“I learned from the best,” I said. “Family taught me.”

It wasn’t untrue. They had taught me everything about planning and pretense and how a person can mistake comfort for virtue.

At the door, Jessica caught my eye. She glanced down, then up, guilt in her throat like a pill too large to swallow. She had sent me a message that morning. It’s done. Thank you for showing me. I’m sorry. I believed the middle sentence. The first and third would take time.

When I stepped outside, autumn seemed more itself. I got in my car and drove. At a red light, I caught my reflection in the rearview and didn’t recognize the woman who didn’t need to explain herself.

That night, my best friend Laura poured me a glass of wine and we sat on her couch while the city did city things outside her windows. “How does it feel,” she asked, “to be the woman who brought a family to its knees without raising her voice?”

“It doesn’t feel like that,” I said. “It feels like finally telling the truth into a room that had made telling the truth illegal.”

Laura, who understands women, handed me a napkin. “And now?”

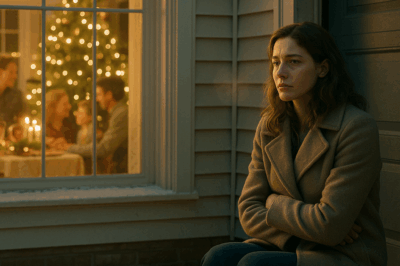

“Now,” I said, the plan I had kept folded in my chest for months finally allowed to unfold, “I’m going to make sure no woman I can help ever walks into a trap thinking it’s a room.”

She tilted her glass toward mine. “To the room we’re building.”

We drank. It tasted like something clean.

Part Two

The first client walked into my office with her shoulders held together like a book whose spine was broken in the mail. She had a file folder and apology in her throat. “Your assistant said I could come even if I don’t know how to describe it,” she said, and then she described it: a husband who hid money in an LLC named after a college nickname; a sister-in-law who met with a realtor “for fun” and offered cash for a rental property that had been marital income last week; a mother-in-law with receipts for silver polish and a daughter’s boyfriend who took photos in parking lots for sport.

I sat where I had sat with James and Michael and William and I told her the sentences I wish someone had handed me like a hot drink. You are not crazy. You are not greedy. This is a language; you can learn it. We will find the money they say doesn’t exist. We will honor the years you gave that aren’t written down anywhere except in the fact that everyone knows who packed the lunches.

The firm—Stone & Harbor, because it amused me privately and because if you say it out loud enough times it turns into something that feels like a place you can stand—grew without banners. Women showed up. Some men did too. Forensic accountants learned to talk in metaphors. A barista I once knew wrote our intake script to sound like a conversation and not a cop. I hired a receptionist who used to be a nurse because she knew how to keep her voice warm when someone said her father’s name into a phone and it sounded like a wound.

Jessica came by the Thursday after the papers were filed. She stood in the doorway contained inside a clothes hanger dress and looked like someone trying to decide which theater to attend where everyone knows the ending.

“I left him,” she said simply. “It turns out I won’t be the first or the last woman to mistake attention for safety.”

“And now?” I asked.

“I like computers,” she said, half-defiant, half-child. “I like finding things that think they’re hidden.”

“You can learn,” I said, and because discriminate compassion is just another form of cruelty, I slid a pamphlet across the desk. Forensic Accounting for Non-Accountants: A Six-Week Intensive. We put her in the Tuesday and Thursday evening class. Six months later, she logged into her first client’s bank accounts like a woman cracking a code on purpose.

Word about Stone & Harbor spread the same way throats spread news: quietly, then everywhere. We didn’t run ads. We ran a clinic at the public library every second Saturday with a whiteboard and coffee and a rotating cast of lawyers who agreed to explain “equitable distribution” to grandmothers in a way that didn’t make them feel like they were being scolded for asking.

Meanwhile—because life insists on running at two speeds at once—Amanda pretended not to see me once in a cafe and then sent me an email two weeks later with no subject. I would like to apologize. The body of the message was an essay about how stress makes people do things they wouldn’t otherwise do and how she hadn’t understood what she was doing was illegal, which was probably true in the same way it’s true that people can’t always name the weather they cause.

She included a line that started with But you have to admit and ended with a request to meet privately. I did not meet her privately. I sent her James Morrison’s receptionist’s number and wished her luck.

George retired from the family business with a press release that used phrases like health concerns and family time and looking forward to the next chapter. The next chapter turned out to be an HOA committee where he could still feel like a person whose opinions were minutes. He lasted three months before someone told him the trash cans could be seen from the street and he resigned in protest.

Eleanor began showing up at charity luncheons with a zeal that looked like penance. She cried into chicken salad more than once. People patted her hand the way you pat a small dog who thinks thunder is personal. The country club ladies turned their chairs two degrees when I walked in and then turned them back when they remembered that I no longer cared.

David was demoted, then laterally transferred, then told they were restructuring in a way that removed the need for his particular seat. He landed a consulting job at a firm that does one good thing and three quietly harmful things, which is about what I expected. His hair went out of style two years before he realized it. Once he came into Stone & Harbor as a client’s soon-to-be-something and pretended not to recognize Jessica. It was the only time I ever watched her hands shake since the night she stood in a room where a woman spoke the truth into a family that thought the truth had to knock.

I saw Amanda again at an event I had avoided every year since being discovered as “she who can end marriages with a spreadsheet.” It was a fundraiser for the legal clinic we loved. I’d given them money and a copy machine and software to manage intake and a promise to keep my name off the program. They insisted on printing it anyway.

Amanda wore the kind of dress you buy when you want to look like you are who you always were. She took a glass of wine and held it like a weapon and approached me as if our scripts had been swapped since the night with the photos.

“Sophie,” she said, and for the first time in the many years I’d known her she said my name like she was trying it on for meaning instead of size. “I wanted to say—” she gestured toward the banner— “I read about what you’re building. It’s… different.”

“Thank you,” I said, because insults metabolize into other things more efficiently than compliments do.

“I was wrong,” she said, the words careful, like moving furniture in a room you used to think was arranged efficiently.

“You were unkind,” I corrected gently. “And you were criminally reckless.” It felt like mercy to name both. “You hurt me in a way you cannot undo. I am not interested in punishing you. I am also not offering you a narrative where we are friends.”

She nodded. The smallest drop of wine fell on her shoe. “Fair,” she said. “My therapist says I’m not good at fair because I thought ‘fair’ meant ‘comfortable.’”

“Your therapist sounds competent,” I said, meaning it.

We nodded at each other. Sometimes closure is not a neat bow but a door that stays unlocked for safety and closed for sleep. I went home and wrote a check to the legal clinic and signed it with a note that said for the woman who learns to leave before she is pushed.

—

And because life is funny about timing, a week later I had a rehearsal dinner to attend—my own. The room smelled like rosemary and something lemon—Laura had insisted it should—and the fairy lights she hung had the audacity to be charming without being saccharine. The man I was marrying was the kind of man who moved chairs without being asked and said he loved me like it was a verb. He had never been rich and did not pretend not to notice the cost of things. He kept cash in his glove compartment like someone taught by a grandmother who didn’t trust banks. He liked my spreadsheets and my silence. He had a daughter who wore pink Crocs with rhinestones and asked questions like bullet points. She was eight and had already asked me to teach her how to find money when a man says he doesn’t have any.

Eleanor RSVP’d no and sent a gift that cost more than her sobriety but less than her guilt. Amanda RSVP’d regretfully unable and sent a card with the last line struck out, likely three times, and then rewritten. David didn’t RSVP. Jessica came wearing a dark dress and a smile that looked like how accountability feels when it’s relieved not to be alone. James led the toast without making it sound like an opening statement. William Parker danced with Laura’s toddler and cried when he thought no one was watching.

When the music got loud, I slipped outside into air that smelled like August has always smelled: a soft surrender. My future stepdaughter followed me out wearing an expression of a person who has a question and knows exactly how much it weighs.

“Is it true,” she asked, “that you catch bad guys?”

“No,” I said. “I find money that thinks it is smarter than women.”

She thought about this seriously. “Can I learn that?”

“You’re already learning,” I said.

I looked up at the night and thought about how my mother would have strung pinecones instead of fairy lights and laughed at my shoes and told me that revenge is a fast meal and you get hungry again, and you have a wedding to get through and a life to build.

—

An email arrived two weeks later from a client in Spokane. Subject: You saved me. The body had no punctuation and more love than I had room for. She had left a man who had taught her that leaving was for other people. We’d found the accounts his mother held and the line in the ledger where love had been replaced by payroll. “Sometimes I hear your voice in my head,” she wrote. “It says, ‘It’s not unkind to save yourself.’”

I forwarded it to our team with a subject line that just said Proof.

And then there was a letter from a judge who had sat through ten thousand sadnesses and written to say our clinic had changed the outcomes in his courtroom because women came in with documents instead of dreams.

And then there was a call from a woman who ran the shelter on the north side who asked if I could teach a class to the residents about credit scores in a way that didn’t make anyone want to die.

And then there was the moment when my stepdaughter stood in a courtroom next to me one Saturday—family day for court watchers—and squeezed my hand when a woman said her name for the first time in public in front of a judge and a man who laughed. My stepdaughter’s grip didn’t loosen. It became a promise.

—

People ask when the grief started and when the anger ended. The truth is they both come and go like weather. Revenge does, too. It arrives like a storm and makes you believe you can reshape anything. But storms wash away as efficiently as they correct. What remains is the work.

I saw Greg one more time in a place that will surprise you if you think stories like mine always deliver their villains to the same endings. I sat in a folding chair in a church basement that smelled like coffee and bleach and heard him tell twenty men in Carhartt jackets and three women in scrubs about how he had learned to apologize without the word but. He’d started volunteering at the legal clinic. He greeted people and made copies and told new lawyers where the extension cord was.

When he saw me, he flushed the color of an error message. We walked to the back where the industrial coffee maker lives, and he told me he sits in on the clinic’s intake sometimes to practice humility. “It’s hard work,” he said, almost proud. “Humility.”

“Most hard work is,” I said, and I poured him coffee, and he poured me coffee, and there was nothing left to forgive.

—

Last month—one year after the settlement came through and the last check cleared and the last apology slid into my inbox—I received a cardboard box in the mail. Inside was a manila envelope labeled Evidence in a firm hand: clippings, spreadsheets, photos from a different woman’s kitchen table, a story written by another set of hands who had realized she was sharing a room with girls like herself. The cover letter began Dear Sophie, I don’t know you but and ended with I thought you’d know what to do. I read it twice. Then I rolled my chair to Jessica’s desk and slid the folder across.

“You’re up,” I said.

She smiled without teeth and picked up a pen.

—

And the Harringtons? They still occupy the same square footage; they just call it something else now. Amanda sits on a nonprofit board that raises money for women “in transition,” and she passes out tote bags with well-meaning quotes. Eleanor throws fundraisers for abused puppies and thinks perhaps she was too hard on people who did not look like her mirror. George writes letters to the editor in which he uses the word “civility.” David runs his consulting practice and does not understand why women do not answer his emails. He will, one day, when a girl with rhinestone Crocs grows up to recognize his type from an RSS feed away.

The thing is, I don’t need their endings to be unhappy for my ending to be good. I sleep. I run. I make pancakes on Saturdays in a kitchen where the light lands on my husband’s shoulders in a way that puts religion in my throat. My stepdaughter keeps a ledger labeled Bad Guys Owe Us and it is mostly jokes and two real names we will handle quietly.

Sometimes I still feel the electric snap in my ribs when I think of the photographs sliding across the table—the way humiliation takes your breath like altitude. But then I remember the sound the pen made when it hit the page in James Morrison’s office and the sound a judge’s gavel makes when truth lands and the sound a woman makes when she stands up from a chair she didn’t know she was allowed to leave.

At the end of a day we won’t remember, I am folding laundry and listening to Laura’s voice on speaker. She’s telling me about a date with a man who collected vinyl and opinions and seemed to value his records more than hers. I tell her my mother would have said that any man who values objects more than conversations is auditioning for a museum, and she laughs hard enough to drop her phone.

A courier knocks. He’s delivering flowers from a client whose name I never say out loud. The card says for the room you built. I put them in water and set them next to the photo of me at a table with James Morrison’s business card half under my hand, the woman who decided revenge would be a bridge and not a destination.

And then, because we promised each other our lives would include more than work, we walk down to the river. The water moves around a thousand stones that don’t ask forgiveness for being where they are.

It turns out that the true opposite of betrayal is not trust; it is stewardship. Of money. Of grief. Of mornings. Of rooms. Of women who learned to tell the truth out loud and to themselves.

If a woman in a dress that remembered a family dinner could step through my door again, clutching photos she thinks are the only story, I would give her a glass of water and a seat and, once her hands stopped shaking, a pen.

“Let’s begin,” I’d say. “What they meant for spectacle, we’ll use for proof. What you meant for love, we will honor on paper. You are not crazy. You are not alone. And when they freeze—because they will—we’ll remind them that warmth is a choice. You chose it first.”

END!

News

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… CH2

My Boss Heartlessly Fired Me At My Mother’s Funeral — His Decision Destroyed Everything He Built… Part One The…

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion Dollar Deal… CH2

My Boyfriend’s Father Called Me Garbage At Dinner — Then I Terminated His Billion-Dollar Deal Part One The room…

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything. h2

My Boss Threatened To Fire Me For Feeding A Silent Child — Her Father’s Identity Changed Everything Part One…

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… ch2

My Sister-In-Law Exposed My “Affairs” At Dinner — Then I Revealed Who Those Men Really Were… Part One The…

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own… ch2

My Family Banished Me To The Freezing Garage On Christmas Eve — Until They Learned I Secretly Own the House…

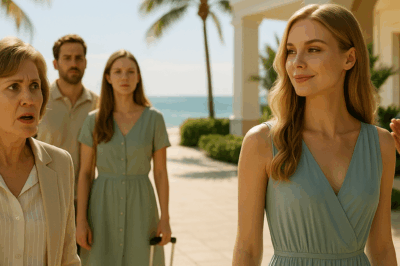

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… ch2

My Mother-In-Law Excluded Me From Vacation — What Awaited Her At The Resort Left Her Speechless… Part One The…

End of content

No more pages to load