My pilot son called: “Impossible. She’s on my flight… not at home!”

Part One

The morning it all began was quiet, ordinary, deceptively simple—like a pond so still you don’t notice the storm clouds gathering in the distance.

I was in the kitchen, rinsing the last of the breakfast plates. The window above the sink looked out on our little garden, where dew still clung to the tomato vines. The sunlight slanted through the blinds, laying neat stripes across the wooden counter. I remember humming an old hymn my husband Mark used to like, letting the soap bubbles catch the light as though they could keep loneliness at bay.

Then the phone rang.

Its shrill cry cut through the stillness, startling me so much I nearly dropped the plate in my hands. I dried them on my apron—an old one, embroidered with sunflowers, frayed at the edges from years of use—and picked up the receiver.

“Mom?” The voice on the other end was my younger son, Micah. Normally, his tone carried a kind of steady cheer, the kind of voice that could make even bad weather seem like a passing inconvenience. But today… today his voice was brittle.

“Yes, honey?” I asked, trying to sound calm though something in his whisper made my heart skip.

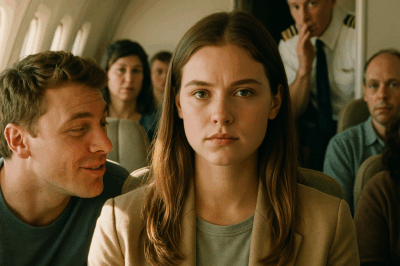

“Something strange is happening,” he said. His words fell like stones, heavy, deliberate. Then came the pause, and I could hear the faint murmur of voices behind him, the clink of metal, the kind of background noise I’d come to recognize from his airport calls. “Sabrina just boarded my flight to Paris. And Mom—” his voice cracked, “—I’m holding her passport in my hand.”

I froze, the dish towel clutched against my chest.

Upstairs, water was still running in the shower. And as though the world wanted to play a cruel joke on me, Sabrina’s voice floated down the staircase. Bright, casual, ordinary. “I’ll be quick, Mom!” she called.

I pressed the phone tighter to my ear, as if force alone could hold my world together. “Micah,” I said slowly, carefully. “She’s here. Sabrina is upstairs. I just heard her.”

The line went quiet—so quiet I could hear Micah breathing, rough and uneven. For a long moment I thought the connection had dropped. Then, with a weight I’d never heard from him before, he said:

“Mom, I’m looking at her right now. Seat 2A. She’s talking close with a well-dressed man. Her hair’s pinned up the same way, her walk the same. I swear it’s her.”

My knees weakened. I reached for the counter to steady myself.

And then the bathroom door creaked open. Footsteps came down the hall. Sabrina’s voice again, light, humming a tune I didn’t recognize. And there she was, wrapped in a towel, smiling like nothing in the world was amiss.

My heart thundered so loudly I thought she might hear it.

That morning, I began the notebook I would later call my ledger of truth. I didn’t know it then, but that simple act would anchor me through weeks of fear, confusion, and betrayal.

The family I thought I knew

My name is Ruth Calder. I have lived in Asheville, North Carolina, for more than three decades. This old house has been my anchor through joy and grief alike. Its floorboards creak like familiar voices, its porch holds the echo of countless evenings watching fireflies with my sons.

I am sixty-six years old, a widow for ten. My husband Mark passed suddenly—ten years ago this spring—and yet his voice still lingers in my mind. He was a man of simple wisdom. “When your mind feels noisy, Ruth,” he once told me, “write down what’s true.” Those words became my compass.

I raised two boys here.

Grant, the elder, is a thoughtful architect, forever bent over his drafting table with coffee stains spreading across blueprints. He married Sabrina eight years ago. She swept into our lives with polished charm, hands that moved confidently in the kitchen, and a smile that lit the house. She gave us Theo—a little boy whose boundless energy made even the most ordinary afternoons feel like holidays.

Micah, my younger son, is the dreamer. A co-pilot who spends his life chasing horizons, his voice always full of warmth when he calls between flights. He never quite learned to sit still, but his heart has always been steady.

For years, I believed our family was whole. Sabrina seemed like the daughter I never had—tidy, industrious, humming as she cooked, patient with Theo in ways that melted my heart. I believed my husband, had he still been alive, would have been proud of the life we’d built.

But Micah’s voice that morning—his whisper sharp with fear—lodged inside me like a splinter. And once you feel the sting of splintered wood, you can’t forget it’s there.

Contradictions

At first, I told myself Micah had made a mistake. A doppelgänger, perhaps. Some woman who looked just enough like Sabrina to trick the eye. After all, wasn’t she upstairs, drying her hair, humming a tune?

But the days that followed betrayed me.

One morning, I watched Sabrina write a grocery list—neat, elegant letters formed with her right hand. The very next day, she wrote a note for Theo’s lunchbox with her left hand—slanted, uneven.

When I asked about it, she laughed softly. “Just practicing, Mom. Keeps the brain sharp.”

I smiled back, but unease had already coiled in my stomach.

Her moods began to seesaw. One evening she sang Theo a lullaby so sweet it left me teary-eyed. The next night, when he spilled water at the dinner table, she snapped at him, sharp and cold. “Careless boy!” she scolded.

Even her clothing seemed wrong. She left the house in a crisp white blouse, basket swinging from her right hand. Hours later, she returned in navy, the basket now in her left. When I asked, she shrugged. “Spilled something on it.”

But what disturbed me most were the little habits—the tiny, intimate details no stranger could get wrong. She stirred soup counterclockwise, though for years I’d seen her stir clockwise. She reached for the wrong cabinet for salt, fumbling as though she’d never memorized the layout of the kitchen she used daily.

It was like living with a woman I knew and didn’t know all at once.

The ledger

One night, my husband’s words returned: “When your mind feels noisy, write down what’s true.”

So I pulled out an old spiral notebook from the drawer, the kind I’d once used to keep grocery lists, and wrote on the first page in careful letters: Ledger of Truth.

Then, line by line, I began to record:

3:10 p.m.—Sabrina leaves for market in white blouse. Basket in right hand.

5:55 p.m.—Returns in navy blouse. Basket in left hand. Explanation: spilled something.

Bedtime—yesterday sang lullaby. Today refused, left Theo crying.

At first it felt strange, almost cruel, documenting my own daughter-in-law like a detective. But once the ink dried, something shifted. My shoulders eased. My thoughts, once tangled, found shape.

Paper was neutral. Paper would not gaslight me. Paper could not lie.

Each day, the ledger grew. And with each entry, I felt myself steadier, even as the world around me grew more unstable.

Others begin to notice

It wasn’t just me.

One afternoon, Mrs. Switum dropped by to return a dish. She handed it over, then frowned slightly. “Ruth, isn’t your daughter-in-law right-handed? Yesterday she gave me this with her left. I nearly asked if she’d hurt her wrist.”

At the bakery, Mr. Paddle said with a puzzled smile, “Strange thing. Last week, Sabrina laughed at my cardamom buns, said I ought to sell them to the king of Sweden. This morning? Barely looked at me. Paid exact change, left without a word.”

But the most painful words came from Theo himself.

We were coloring together one quiet afternoon when he set down his crayon and whispered, “Grandma, I like nice-voice Mom better than storm-voice Mom.”

My throat tightened. I pulled him into my arms and kissed his hair, tears stinging my eyes. Out of the mouths of children come the truths we adults work so hard to deny.

Following her

At last, I knew I needed more than notes. I needed proof.

One Saturday, Grant was at the office and Theo at a school activity. Sabrina came downstairs in a pale yellow dress, wicker basket on her arm. “Off to the market,” she said with her usual smile.

I waited until the gate clicked shut. Then I wrapped a shawl around my shoulders and slipped outside, careful to keep my distance.

She walked the familiar street, but when she reached the corner, she didn’t turn right toward the market. She veered left, down a narrow lane lined with rusted fences and peeling paint. My pulse thundered as I ducked behind a row of bicycles.

She knocked softly on a worn wooden door marked 14. It creaked open, and she stepped inside.

Minutes later, I returned home breathless. And there she was in the kitchen, calm as ever, chopping vegetables in a different blouse.

Sleep abandoned me that night. The image of her yellow dress disappearing into that alley haunted me.

By morning, my decision was made.

Isla

I tucked a family photo into my purse—the one with Grant, Sabrina, and Theo smiling on the porch—and walked back toward number 14.

The alley was quiet, sunlight barely reaching the cracked pavement. My knuckles trembled as I knocked.

The door opened, and I gasped.

It was her. The same eyes, the same height, the same dark hair. But her posture was different—nervous, shrinking. She gripped a rag as though she might slam the door.

Before she could, another voice called from inside: “Isla, you can’t hide forever.”

A young woman appeared—Jenna Park, she later introduced herself, a nursing student renting the other room. She looked at me kindly and said, “Come in, Mrs. Calder. It’s time you knew.”

The house was small, humble—concrete floors, patched walls, the faint smell of disinfectant. An older man lay coughing on a cot in the corner, covered by a frayed blanket.

The woman before me lowered her eyes. Her voice shook. “I’m sorry. I’m not Sabrina. My name is Isla Hart.”

I clutched the photo in my purse. “Then why have I seen you in my home?”

She twisted the rag in her hands until her knuckles whitened. “Because she pays me. She told me to fill in, to watch Theo, to go to the market, to be her whenever she couldn’t. My parents need medicine. The money was too much to refuse.”

Jenna laid a worn envelope on the table. Inside were faded hospital papers. The date of birth stopped my heart. Identical to Sabrina’s. Same hospital. Same hour.

Twins.

Two sisters.

The contradictions in my ledger, the mood swings, the shifts in handwriting, the clothing changes—it wasn’t imagination. It was two women living one life.

And then Jenna spoke softly, almost reluctantly: “One night, I saw Sabrina with a man named Victor Lang. They were laughing, calling each other honey.”

Micah’s voice came back to me like a blade: Seat 2A, leaning close like a couple.

The puzzle snapped into place.

My family had been living under a shadow.

My pilot son called: “Impossible. She’s on my flight… not at home!”

Part Two

I walked home from number 14 along the long way, past the bakery and up the hill where the oak roots ribbon the sidewalk. I needed the extra minutes to flatten the tremor in my hands and keep my mind from spinning off its axis. Truth, I told myself, is heavy but carryable. Lies look light, but they hollow you out.

When I reached the gate, the house looked the same as it had that morning—the geraniums flaring red in the window box, the porch boards bleached by sun—but in me something had been rearranged. I put the kettle on and set my ledger on the kitchen table. For once, I didn’t write a time or a verb. I wrote a sentence across the middle like a line of demarcation: It is time to bring light into the room.

I called Micah. The airport hum roared behind his hello.

“Bring me everything official from that Paris flight,” I said. “The boarding list, the gate incident, anything with an inked stamp. Tomorrow. We’ll put it on the table.”

“Mom—are you sure?”

“As sure as a person can be and still wish she were wrong.”

He did not argue. “I’ll be home by noon.”

I slept in pieces that night. I dreamed of two women walking through my house in relay, one taking the spoon from the other’s hand, one picking up the baskets the other set down. I woke with the dry taste of fear in my mouth and a resolution strong enough to stand on.

Setting the table for truth

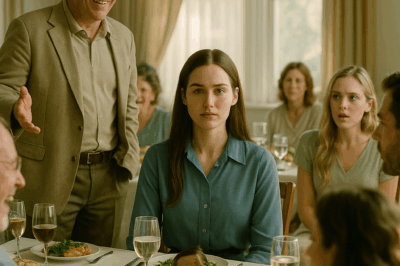

The next day, I turned our table into a stage where only facts could speak. I ironed the white cloth and smoothed it until the linen shone. I set three beeswax candles in the center and polished the old stoneware until I could almost see my reflection. Roasted fish went into the oven—the way Theo liked, with lemon wheels tucked under the skin. Chili cornbread baked until its top cracked like parched earth. A pitcher of sweet tea sweated on the counter. These were comforts, yes, but also signals. In this house, we break bread before we break apart; we make room for sweetness even when the truth is bitter.

At noon, Micah arrived with a manila envelope hugged to his chest. He kissed my forehead and set the envelope gently on the table. Inside were copies—boarding list, cabin crew notes, a photocopy of the passport as it looked when found. On the passenger manifest: Sabrina Calder, Seat 2A. His neat annotation in the margin: Observed with male companion, Victor Lang—boarding Group 1.

Micah’s hands shook as he laid it out. “Mom, I didn’t want to believe it either.”

“I know.” I folded his fingers into mine. “And we will not use this to punish. We will use it to protect.”

I called Jenna at number 14. She agreed to come after her hospital rotation, voice steady as a metronome.

“And Isla?” I asked.

“She’s scared,” Jenna said. “But she wants to do the right thing.”

“Then tell her she will not walk alone.”

I breathed. Then I called Grant and told him there’d be dinner at seven. He heard something in my tone and didn’t ask why. He said he’d be there.

The hour arrives

I lit the candles just before seven. Their small flames lifted the room’s shadows into corners. The fish rested under foil, the cornbread on a board. I pulled Theo’s favorite chair a little closer to mine without thinking.

Grant came first, tie loosened, fatigue written across his eyes like penciled hatching. He hugged me with one arm and inhaled the smell of dinner. “What’s the occasion?”

“A family one,” I said, and kissed his cheek.

Sabrina arrived a few minutes later in a pale blue dress that made her look like the good version I kept wanting to remember. She placed a hand on Grant’s shoulder, kissed Theo’s hair, and sat down without a ripple. She was glossy as a magazine page—smile, posture, poised silence.

I had set a fourth place. When the knock came, Theo glanced at it, then at me. I nodded and opened the door.

Isla stood on the porch, fingers laced so tightly her knuckles were the color of milk. Behind her, Jenna waited, chin raised like a small-town saint in scrubs. Isla stepped in and the room felt—how can I say it?—true and impossible at once.

Theo’s eyes widened. A crease formed between his brows, that small furrow he gets when a riddle is just beyond his reach. “Why are there two Moms?” he whispered.

I went to him first. I always will. I knelt so we were eye to eye. “Sweetheart, there aren’t two moms. There are two sisters. And tonight, we’re going to be very brave and tell the truth together.”

Sabrina’s smile tightened like thread drawn through fabric. Grant’s gaze flicked between the women, then settled on me. “Mom?”

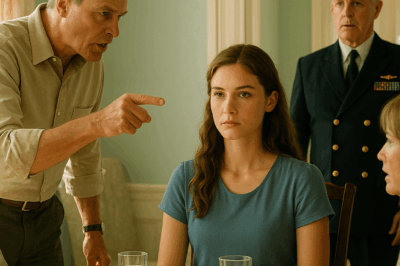

I took my seat, opened the ledger, and read two pages aloud—dates, times, actions—without adjectives, without a single speculation. Then I set Micah’s envelope on the table and slid out the manifest. “This is what your brother brought me,” I said. “Seat 2A to Paris. The name printed there is Sabrina’s.”

Micah, standing in the doorway like a penitent altar boy, added softly, “I saw her. With a man.”

Jenna stepped forward, palms open. “My name is Jenna Park. I rent the back room at number fourteen.” She spoke clearly, like in a deposition. She described the café across the river, the close laughter, the word honey, the glint of a cufflink I recognized from the manifest notation.

Then I turned to Isla. I had promised she would not be alone, but the part she had to do herself, no one could do for her. She lifted her chin. “I am Isla Hart,” she said. “Sabrina hired me to stand in when she was away. I shouldn’t have said yes. I was wrong. I was desperate.”

Silence gathered in a high, ringing tone. Then Sabrina’s hands, open on the tablecloth, curled into fists.

“Fine,” she said at last, her voice clipping each word. “Yes. I have someone else. His name is Victor. He gives me the life I deserve. I’m tired of this small house and this small town and carrying everyone’s ordinary.”

Grant looked like a house hit by a wrecking ball—dust lifting at once, then nothing holding. “And Theo?” he asked, not moving. “Was he your ordinary?”

Theo’s lower lip began to tremble. He stared at the cornbread as if it could answer for all of us. “Grandma,” he whispered, “did I do something bad?”

I pulled him onto my lap. “No, my love. No.” I rested my cheek on his hair and looked up at the adults. “Children do not cause adult choices. Adults must carry what they choose.”

Sabrina stood so quickly her chair skittered back and knocked the baseboard. She pointed at Isla as if she were pointing at a mirror. “You were supposed to make this easier.”

Isla flinched. Jenna placed a hand on her arm like laying a cool cloth on a fevered forehead.

Sabrina grabbed her purse, jutted her chin, and walked out. The door closed with a soft click that landed like a gavel. The candles kept burning. The fish cooled. And in that dim golden light, the life we had been pretending slid off the tablecloth and disappeared.

We did not eat much. Theo chewed a corner of cornbread and pressed his shoulder into me like he was trying to grow roots. Grant stared at his plate and then at his son. Micah gathered the papers back into their envelope with the tenderness of someone handling relics. When he left, he pressed it into my hands. “Keep it,” he said. “This is our record.”

The days after

Shock is a quiet animal. In the morning, it pads behind you as you make coffee, sit on the step to tie your shoe, answer an email you cannot remember writing. It curls at your feet when you stare through a window and only realize the glass is there because your breath fogs it.

Grant slept on the couch the first two nights, as if staying at a neutral altitude might keep him from falling. On the third day he cleared a drawer, then a closet. Papers appeared on his dining table—consultations, a checklist for separation, a list of documents to compile. The black pen in his hand seemed to leave grooves in the fibers.

I cooked too much and left containers on his porch. He didn’t always eat, but when the container came back washed, I understood it wasn’t about food. It was about heat carried from one house to another.

Theo oscillated between silence and sudden storms of questions, each question landing like hail. Where did Mom go? When is she coming back? Why is Auntie Isa scared? Did I spill too much water? Did Mom get mad at the plane and go to time-out in Paris?

To each question I gave exactly one honest sentence and an arm around him. Your mom is away with someone she chose. Adults make choices and we will keep you safe. You are not the cause. And when it was too much, I borrowed the trick Mark used with the boys after nightmares: we counted things we could see, name by name, until the world felt named enough to be bearable.

Isla did not come to the house for a week. I told her to take no steps forward until she had caught her breath. Guilt is a heavier coat than grief because you think you chose it. She had chosen part of it, yes. She had not chosen the rest. I told her so more than once.

On the eighth day, she called. “May I bring soup?”

“Bring yourself,” I said.

She came with a thermos and stood on the porch as if the threshold might judge her. Theo stood behind my legs and peered around at her. “Are you the nice-voice one?”

She swallowed. “I hope to be.”

He nodded solemnly. “Okay.” And just like that he led her to the rug and fetched the box of crayons. He handed her a blue one. “For sky,” he instructed.

They drew a clumsy bird together—blue body, orange feet, a beak straight as an arrow. Isla laughed once, softly, then pressed her lips together as if she were sealing the laugh to keep from breaking.

“Leave the soup,” I said later, “but stay for dinner.”

She shook her head. “I don’t want to—”

“Be an imposter?” I finished. “Then don’t impersonate. Come as yourself.”

She stayed. She washed dishes. She dried them the way my mother did, laying each plate like a coin on the rack. When she left, the kitchen felt larger and lighter, as if something had been returned, not removed.

The legal weather

There is the weather the sky makes, and there is the weather paper makes. In the weeks that followed, we lived under both. Asheville wore late summer like a shawl; leaves went dusty at their edges, cicadas rasped, thunderstorms failed to commit. Meanwhile, the courthouse produced barometric changes of its own: filings, motions, a mediation calendar that placed our private grief on public time.

Sabrina did not fight for custody. She did not fight for much at all. She signed where lines told her to put her name. She appeared once with Victor, who wore a navy suit and a watch I could have bought a used car for. He did not look at Theo when we passed in the corridor. He looked at the clock.

Grant and Sabrina divided property with the sterile arithmetic of strangers. There was no shouting in rooms where rules forbid it. Only pens and folders and the occasional cough. When it was done, the stamp thunked down like thunder moving off into the distance.

I walked with Grant to the parking meter and put in two quarters though we no longer needed the time. He leaned an elbow on the roof of his car and stared at nothing. “It’s like I broke my leg and the hospital put me in shoes,” he said. “Legal shoes. But I can still feel the break.”

“Shoes are for walking,” I said, and touched his cheek. “The break will knit while you move.”

Community eyes, community hands

A small town sees. It also holds. The bakery slipped cinnamon rolls into Theo’s paper bag “by accident.” Mrs. Switum pressed my palm around a small bottle of blessed water from her church and said, “For courage.” The men at Grant’s office quietly redistributed deadlines. At church, where Mark and I had sat side by side for twenty years, Pastor Elise stepped down from the chancel after the benediction and said only, “You are loved,” which was worth more than any sermon on long-suffering I’ve ever heard.

Of course there were the other eyes—the ones that love a story more than they love the people in it. But all I had to do was look to the sides and find one pair of steady hands, and the hungry looks faded like moths from a porch when the light goes off.

Micah’s reckoning

Micah had his own quiet storm. I found him one afternoon in the garage, oil on his knuckles, kneeling beside his motorcycle like a man in prayer.

“I keep thinking,” he said without looking up, “that if I had never called, the house would still feel whole.”

I set a stool and sat. “And then?”

“And then we’d be living a lie I helped keep alive.” He wiped his hands on a rag. “That’s the worst puzzle: to do the right thing and want—just for a second—to undo it.”

I put my palm on the crown of his head the way I did when he was a boy and bent over model planes. “Son, a pilot who ignores the instrument panel because the sky looks fine is not brave. He is dangerous.”

He exhaled, a sound like a pressure valve releasing. “Copy that,” he said, and a ghost of a smile returned to his mouth.

The slow braid of days

Grief and newness began to braid. Theo’s bedtime turned into a low-lit ritual: bath, pajamas, two stories, one song. Some nights he asked for the lullaby. I sang in the thin voice of grandmothers everywhere and asked Isla to hum along if she felt steady enough. She did, stumbling at first, then finding a note that was hers.

On Saturdays, Isla learned the markets: which stall sold the early apples, which butcher wrapped paper tightest, which cashier gave Theo a sticker if he stood on the painted footprints and waited his turn. She learned to tie his sneakers and the fastest route to school when the train blocked the main crossing. She learned, in a hundred small ways, how to be present. Not as a shadow. Not as a substitute. As herself.

One afternoon in October, I stood at the porch rail and watched Grant teach Isla how to tie tomato vines that were mostly spent now, only a handful of green globes left, stubborn against the season. “Loop, twist, lay it easy,” he instructed, and their hands brushed once, then again on purpose. Theo galloped through the grass with a stick he declared a lightsaber, saving the universe a dozen times before supper.

That night, after dishes, Grant lingered at the sink and looked out the window to where Isla gathered laundry from the line. “I feel like a man who found a key after his house burned down.”

“Sometimes keys open gates,” I said. “Not back doors.”

He nodded, and the nod said more than his words could have borne.

A letter with no return

In mid-November, a letter came from Sabrina. No return address, just a city postmark, the handwriting known to me as well as any woman’s I’ve loved and less so than her mirror’s. In it she wrote that Paris was “exhilarating” and “relentless,” that Victor traveled often, that she had started a language class and missed the specific way the mountains looked at dusk from our porch. She did not ask about Theo. She asked whether a set of copper pots had been packed with her things; if not, could I send them?

I sat at the table with the letter and looked at the window where dusk was, at that very moment, painting the mountains the bruised color she remembered. I did not flinch when the ache came. A person can be both wrong and loved. Those truths don’t cancel each other. They sit at the table together, and one of them eats while the other watches, and somehow you get through supper.

I did not send the pots. I sent a photo of Theo at the harvest carnival holding a paper turtle he had painted a scandalous green. I wrote one sentence: He is growing. I did not sign Love. I signed Ruth.

Christmas without and with

Holidays mark absence harder than ordinary days. The house smelled of pine and nutmeg. Theo made a chain from red paper and counted links to the twenty-fifth. “Will Santa know which chimney?” he fretted.

“Santa is a logistics professional,” Micah said solemnly, and taped a small map to the hearth.

On Christmas Eve, we went to the candlelight service and sang Silent Night with wax pooling in our palms. Isla stood at the aisle end, and during the final verse Theo reached over and slid his fingers into hers. She startled, then squeezed back. It was the smallest covenant and a complete one.

We set out a plate of cookies. Theo wrote a note for Santa with careful letters. Dear Santa, please give Grandma the biggest hug. She keeps the ledger of truth. He looked up at me. “I spelled ledger right, right?”

“Perfectly,” I said, and kissed his temple.

Later, after he slept, Grant and Isla sat at the kitchen table with mugs of tea. The tree lights blinked in the next room. They did not hold hands. They did not speak much. They sat together in the warm, saturated quiet of a house that has chosen, again, to be a home.

Spring’s answer

By March the dogwoods laced the streets with white and the air smelled like rain deciding. We had moved from surviving to building. Not triumphantly, not with trumpets, but with the steady labor of people who have learned something about what endures.

Grant asked Isla to take a Saturday off with him while I kept Theo. They drove to the Arboretum, then to the overlook Mark loved, the one where the mountains line up like cut paper. When they came back their cheeks were wind-bright, and they carried a sack of boiled peanuts they pretended were for me but ate half of before tea.

On a mild Thursday in April, a small thing happened that felt as big as a vow. Theo brought home a school form—a permission slip for a field trip to the science museum. At the signature line he waited with a pen. “Who should sign?” he asked, earnest. “It says parent or guardian.”

Grant reached, then paused. He looked at Isla. She looked at him. And then, very gently, she took the pen. “I’ll sign,” she said, “if that’s what you want.”

Theo nodded. “Yes, Mom.”

The word fell so natural and so quiet that no one breathed for a second. Then we all did, together, like people resurfacing from a long swim.

The backyard lights

We strung lights in the backyard in June, the kind that make every evening look like a celebration even if you’re only eating leftover potato salad. I rescued a table from the thrift store and painted it the dark green of the mountains after rain. I set mason jars with cut zinnias, because nothing says we are still here like flowers that look like they’ve decided to live forever.

Grant asked Isla to marry him the way men who have been through a wreck ask: not with spectacle, but with a ring and a question that carries the weight of last times and the hope of firsts. He did it while we were shelling peas, an emerald world rolling into a blue bowl. “Will you stay?” he asked, and the word marry stood behind stay like a witness. Isla cried, then laughed at herself for crying, then said yes as if she were saying her truest name.

Theo danced in place and asked if best men could be seven. “They can if they’re brave,” Grant said. “And if they can keep the ring safe for twelve whole minutes.” Theo saluted. “Sir, yes sir.”

We kept the wedding small. Pastor Elise stood under the hackberry tree and spoke the only vows I have ever needed: Do you promise to do your best, to say sorry first when you can, to protect what is small and repair what you can repair? They said I do like stepping onto a bridge they had themselves hammered together plank by plank.

When it was time for the rings, Theo pulled the box from his pocket with grave ceremony and popped it open with both thumbs. For a second I saw the boy and the man braided in him and felt Mark beside me like a warm draft. I heard him say, as he said when the boys were small and fighting over a toy, “Choose the kind thing, Ruth. The kind thing is usually the brave thing in disguise.”

After the toasts, the music, the cake, I went into the kitchen to refill the lemonade and found my ledger on the counter where someone had moved a bowl. I laid my hand on it and felt a pulse under the cardboard as if the book itself were a living heart. I opened to the first page and read my own early entries—questions posed as facts, facts written with a shaking wrist, sentences that looked like they were forged out of necessity and fear. Then I turned to the back and found blank paper.

I picked up my pen. I did not write times. I did not write suspicion. I wrote a list of truths that no longer required proof.

Theo laughed today the way a creek laughs over stones.

Grant asked for help carrying chairs and did not apologize for needing it.

Isla stirred the soup clockwise while telling a story about her mother’s kitchen.

Micah texted a photo from the cockpit at dawn: horizon like a promise.

I slept six hours and woke without dread.

I closed the ledger and ran my palm over its cover. It had been my raft. But rafts, I know, are not houses. You do not live forever on emergency equipment. You use it to reach shore, then you thank it and step onto ground.

A last call, a clear sky

On a late summer morning almost a year after Micah’s first call, the phone rang again while I was drying the last breakfast plate. I smiled at the symmetry of it and answered.

“Mom,” Micah said. His voice sounded young and old at once, like a song I knew by heart. “I’m wheels up in twenty. Just wanted to hear your voice.”

“You just did,” I said. “And I’m making peach cobbler for when you get back.”

“Save me a corner,” he said. “The one where the syrup gets chewy.”

Before he hung up, he asked, careful, “You good?”

I looked around the kitchen: the strung lights visible through the window, the backpack by the door with Theo’s name stitched in wobbling letters, the bouquet Isla had cut from the garden standing like fireworks in a jar, the blueprint Grant had left open on the table with a coffee ring baptizing one corner.

“I’m good,” I said. “We’re good. Truth’s on the table, and everyone’s got a seat.”

After I set the phone down, I did something I had not done in months. I pulled the ledger from the drawer, not because I needed it, but because I wanted to mark the moment when needing turned to choosing. I opened to the very last page and wrote a single line in a hand that did not shake:

The light is in the room.

Then I tucked the notebook back into the drawer with the spare envelopes and stamps. I wiped the counter, rinsed the bowl, and took the cobbler from the oven. The crust bubbled at the edges, sticky-sweet. I set it to cool on the rack and opened the back door to let the morning in.

The yard smelled like cut grass and possibility. Across it, under the line of backyard lights we had forgotten to take down even though the wedding was long over, Grant was showing Theo how to check air in a bicycle tire, and Isla was hanging dish towels side by side like flags from a small, quiet nation.

I stood there a moment, holding nothing, and felt the precise weight of the world as it should be—not light, not heavy, but honest, which is another way of saying bearable.

If you have read this far, I’ll leave you with the lesson I learned the hard way and would have rather learned easy: keep a ledger when your mind is noisy. Write down what is true. Not to make a case, but to make a path. When the fog lifts—and it will—you’ll find your own footprints leading you home.

And when the phone rings with something impossible, answer it. The truth might be painful, but it is always, always the beginning of the way out.

END!

News

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives. CH2

My Brother Mocked Me on the Plane — Until the Pilot Whispered My Call Sign to Save 200 Lives …

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” CH2

Family Said I Failed, Banned Me From Grandpa’s Funeral. Then 12 Marines Saluted me:“General, Ma’am.” Part One My name…

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… CH2

My Brother Mocked Me As A “Useless Soldier” — Until My Call Brought The FBI To Their Funeral… Part…

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… CH2

My Father Called Me A Traitor — Until An Admiral Said 3 Words That Made Him Frozen… Part One My…

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. CH2

My Family Demanded Everything in Court—Then I Handed the Judge One Paper That Made Police Storm I. Part One My…

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. CH2

My Father Mocked Me in Front of Everyone – Until His New Daughter Realized I Was Her General. Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load