My Parents Watched My Sister Push Me Down the Stairs. The Hospital Security Camera Caught Everything

Part One

My name is Cassandra Wilson, and I was thirty-one years old the night the staircase at Massachusetts General became an X-ray of my family.

I remember the feel of the metal push bar under my palm—cool, solid, reassuring. The stairwell beyond was bright and echoing, the kind of space hospitals build for evacuation drills and quiet phone calls. I’d chosen the stairs to avoid the tight little box of the elevator with my parents and my sister—six floors pressed unbearably close with a lifetime of grievances. I told my father I needed the exercise. He shrugged, and the doors slid between us.

Bria slipped out of that elevator at the last second as if mercy had pulled her by the wrist. “I should talk to her,” she told our mother, just loud enough for me to hear.

Bria is three years younger and has always been striking, the kind of beautiful that wins raffles and loans and benefit of the doubt. She learned early how to use it: tears like buttons she could fasten or unfasten, smiles that bent adults to their knees. In the affluent Boston suburb where we grew up, people loved to say the Wilson girls had it all. They didn’t see the birthdays with two names frosted on one cake because Bria couldn’t stand a day that wasn’t hers. They didn’t see my father calling me dramatic when I protested. They didn’t see a family therapist who told me at sixteen that I was experiencing normal sibling rivalry while Bria dabbed at dry eyes and said she wished her jealous big sister would be kinder.

Our grandmother, Martha, saw. At eighty-four, hospitalized with pneumonia, she still smile-lit a room when I walked in. We’d spent the afternoon talking about spring bulbs and my new promotion—marketing director at a tech firm, a win that had barely earned a nod at home. Bria arrived two hours late, gift bag swinging, talk already angling toward jewelry. “I should have the sapphire necklace,” she said, lifting a compact mirror to her own eyes. “It matches.”

When Grandma dozed again, I saw her slide something from the bedside drawer into her purse. I made a note to check later. My mother called it being prepared. My father called me unkind for objecting. We left at seven with the tension folded into our coats.

Bria’s voice in the stairwell dropped the sugar it wore for our parents. “I saw you watching me in Grandma’s room. Always the self-righteous one, aren’t you.”

“I’m leaving,” I said, taking concrete carefully in flat shoes. “Not here, Bria.”

“You changed her mind about the will,” she hissed, footsteps quickening. “You think I don’t know. The beach house. The one Dad promised me. You been playing saint in there, helping with her stretches, whispering little stories. She changed it because of you.”

“I don’t know anything about her will,” I said, stopping on the landing. The sound of our breath bounced off painted cinderblock. “And if she changed it, that’s between her and her lawyer. Not you. Not me.”

“Everyone plays favorites,” she said. “It’s not my fault no one picks you.”

It would have been almost funny if her eyes hadn’t gone flat. I turned. There was the hard shove between my shoulders, a two-handed promise. For a fraction of a second life suspended me over a gap and then dropped me into it. I reached for the rail and found air. Shoulder, hip, skull, ribs—each struck with an intimacy I had never asked for. Pain flared bright white, then red. The world slowed and trebled. Somewhere very far away I heard my own voice rip the echo into shreds.

I lay on the landing between the third and second floors and stared up through a field of static at my sister’s satisfied mouth. The expression snapped shut when the stairwell door banged open and my parents rushed in.

“What happened?” my mother cried, rushing to the girl who had done the pushing. My father wrapped Bria in his arm like a rescue blanket.

“It was an accident, right, Bria?” he asked in the careful tone he used with bankers and judges.

“She fell,” Bria said in a small trembling voice on cue. “I tried to catch her—she was going too fast.”

I tried to speak, to shape words around the broken tide of my ribs. What came out was a sound I wouldn’t recognize as mine if it hadn’t hurt so much.

The door below slammed. Head nurse Marlene appeared with two orderlies and the kind of triage voice that can glue a thousand days together. “Call a code. Backboard. C-spine.” Kneeling, she checked my pupils, then—so fast I would have missed it if I hadn’t been starving for a witness—flicked her gaze to the ceiling corner. A camera. Red light blinking.

She saw me see it. The smallest nod.

“Don’t move her yet,” she told the orderlies. To another nurse in the doorway, she said evenly, “Note the time of the incident and secure all relevant footage. Standard procedure.”

They slid a board under me and strapped me down, and a wave of pain rolled high enough to block out everything but the lights sliding by overhead. In the ER my body turned into a map for strangers to read: CT scan, wrist X-ray, chest X-ray. IV. Oxygen. I drifted and surfaced and drifted, hearing fragments like ships’ horns in fog—concussion, fractured distal radius, non-displaced rib fractures, pulmonary contusion.

Once, I passed the waiting area and saw my parents. My mother was wiping tears from Bria’s cheeks. My father stood with a police officer, hands sketching a calm, practiced story in the air. “My daughters were walking down the stairs,” he said. “The older one was going too fast, lost her footing. The younger tried to catch her.”

I slept on a wave of medication and woke to sunlight and Tracy, a young nurse with a braid like a rope. “Name?” she asked. “Pain level?” She was taking my blood pressure when my family entered like actors sweating their cues. Yellow roses. Get-well bear. A shoulder to catch the light.

“It wasn’t an accident,” I said, my voice rough from tubes. “Bria pushed me.”

Silence rang. My mother let out a strange little laugh. “The medication,” she said softly, patting the hand not wrapped in plaster. “You must be confused. You fell, sweetheart.”

My father placed papers on the tray. “Insurance forms,” he said briskly. “We should have this behind us before you’re discharged.”

“There’s a camera in the stairwell,” I said. “It will show what happened.”

A muscle jumped in his jaw, the same one that flexed when deals turned. Bria’s eyes filled overnight with water. “How can you say that?” she whispered. “I tried to save you.”

Nurse Tracy slipped out. Head nurse Marlene slipped in with the quiet tread of someone who has learned how to arrive without making things fly apart. She checked my IV, my bandage, the angle of the window blind. “How are we feeling?” she asked.

“Pushed down a flight of stairs,” I said.

“Interesting choice of words,” she said, her eyes meeting mine. “I reviewed the security footage. Hospital protocol.”

I felt the weight between my ribs shift, not to relief exactly—relief was still too expensive—but to possibility. “And?”

She didn’t look at my family. “And what I saw was not an accident.”

She waited until my parents were in a meeting with Grandma’s doctor to slip a tablet from her pocket and tilt it toward me. It was like watching a silent movie in which I had the starring role and no lines: me pushing the door open, Bria sliding in after, my shoulders tight with anger I had tried not to carry into the stairwell; our bodies as punctuation—stop, turn, argue; my turn to continue; her hands; the push; the trajectory you can draw with a ruler; gravity doing what it always does. Another angle from the landing below caught her face, and my stomach lurched for reasons the morphine didn’t touch.

“We’ve preserved footage from three cameras,” Marlene said. “Hospital security and the police have copies.”

When my parents came back, they came with officials this time: two security officers and Gregory Dawson, the hospital administrator, face set like someone deciding how to say a thing no one wants to hear.

“We reviewed the footage,” Dawson said. “It shows your younger daughter deliberately pushing your older daughter.”

My father moved decisively to the second stage of a plan he had used before: minimize, soften, reframe the knife as a spoon. “Family matters can be—” he began.

“Pushing someone down concrete steps is not a family matter,” Marlene said. “It’s assault.”

Bria tried every mask. The trembling tearful confession: “We were arguing; I reached out; I never meant—” The righteous anger: “The angle was wrong; Cassandra was unsteady; I was trying to help.” The plea: “She’ll ruin us.”

The officers asked for statements. A female detective introduced herself the way professionals do when they know the next words will matter. “I’m Detective Sarah Harris,” she said. “Miss Wilson, when you’re ready.”

She took my statement with the patience of a woman who has heard the same lies so many times she can recite the meter. When I hesitated around the corners of old injuries, she didn’t fill in the blanks, just waited with a pen over paper until the words learned to walk out of my mouth. “There’s a pattern,” she said, flipping through a notebook. “Hot coffee at a family dinner? A college roommate on icy steps? An apartment door closed on a hand? A boyfriend who decided to keep the hole in his wall rather than press charges? We’ll be talking to all of them.”

“They’ll say it was an accident,” I said.

“They always do,” she said. “And sometimes it is. That’s why we gather evidence.”

That night in a room where machines sighed and blinked, I heard my parents arguing in the hall about getting our story straight. I stared at the ceiling tiles and saw dots and squares and dots and squares until the pattern broke and my mind landed somewhere that looked like the truth: I had spent a lifetime being the family peacekeeper because I had been told peace was my job. I had never been given peace. I had given it; they had taken it. There is a difference.

The next day my boss called because my mother had called him first. “Is everything all right?” he asked, voice cautious, as if the words might break a thing already broken.

“My sister pushed me down a flight of stairs,” I said. “There’s footage. I’ll be out a few weeks.”

“You’ll be out as long as you need,” he said. “And you’ll come back to the same job.”

Not everyone was kind. Bria posted her version and was believed by people who had always enjoyed the spectacle of a scapegoat. A college friend messaged me to say she was praying for me and then asked if maybe I had been drinking. I learned which people in my life did not deserve to be invited to the quiet. I learned that some kinds of silence are useful.

Aunt Jillian—my father’s sister—swept into the hospital with the scent of gardenias and memory. “Robert is furious,” she said cheerfully, kissing my forehead. “Which tells me we’re doing something right. You’re coming to stay with me.”

I moved into her little Cape, a house with creaky floors and a kitchen table that knew how to hold elbows. Physical therapy was medieval and exact. Dr. Stein, the hospital psychologist, listened as I built a map of a house where my sister was a sun and I learned to be a planet that kept itself from spinning off the edge. “Golden child and scapegoat,” she said. “Classic pattern. It feels like weather. It isn’t. It’s choices made and remade for years.”

She taught me how to recognize the weather forecasts that live in your head and to check them against the sky.

Two weeks later Bria’s ex-boyfriend called. He had texts. Threats and apologies and threats again, stitched like a quilt you wouldn’t put on a bed. Detective Harris collected them like she was gathering rainwater on a roof.

Grandma got stronger. She asked to see me. “I changed my will,” she said in a voice that used to read me Little Women on the summer porch. “Because I watched how they treated you and how you loved me. And because I’m tired, Cassandra. I’m so tired of pretending.”

She handed me a letter she had written after my promotion. The ink wandered a little, but the words held steady. You are not wrong. You are not dramatic. You are not forgotten. I cried in a way that felt like a body moving old ink around so it could dry.

My parents came to Jillian’s trying on a last-minute olive branch painted white. Bria stood between them, a child again on cue, small and breakable and calculating. They brought papers. “Sign this reassignment,” my father said. “Withdraw the accusation, and we’ll handle this as a family. Bria will attend therapy.”

“No,” I said. I had been practicing that word in Dr. Stein’s office with my hands around a teacup and in front of a mirror with my shoulders back. I said it again, and the house didn’t fall.

“After everything we’ve done for you,” my mother said, as if the six broken birthday parties had been investments expecting returns. Jillian laughed. “Eleanor,” she said, “even now?”

My father threatened to disown me. He did not realize that a threat is only frightening if the thing being taken has value. When they left, Jillian and I sat on her back steps and watched one star fight light pollution and win. “Am I doing the right thing?” I asked.

“The right thing is rarely the easy thing,” she said. “You’re doing it anyway.”

On the morning of the preliminary hearing, the courtroom smelled like wood polish and urgent coffee. Judge Peterson, a woman with hair like steel wool and a face that said she had raised teenage sons by herself, called us to order. The video played on a monitor wheeled in from the clerk’s office. No audio, no narration, just the implacable geometry of motion: hands, back, push, fall. In another angle, Bria’s face before she put her hands to it.

Richard Cooper, my father’s lawyer, argued that the footage showed an emotional exchange, not malice. He said sisters shoved each other on stairwells all over America and didn’t end up in felony court. He said a thing about the camera angle. Judge Peterson looked at him like she wished men would try new tactics.

Nurse Marlene told the court she had watched the video three times, that she had pressed record because she had been a nurse a long time and had learned when to document and when to be quiet and when to do both. Dr. Winters listed my injuries without drama. The hospital security officer explained how three cameras with overlapping coverage did not have the power to conspire.

I read my impact statement: about birthdays and therapists and accidental spills, about being asked to be reasonable because their feelings were, about holding peace like a bruise. “My bones will heal,” I said. “The part that doesn’t above my ribs may take longer.”

Bria cried on the stand. She admitted the push in passive voice. She spoke about stress and worry and the difficulty of watching a grandmother suffer. She said words like “momentary lapse” and “tragic accident.” Cooper reminded the court she had agreed to therapy. Detective Harris presented texts that spelled legacy in lowercase. Grandma’s deposition came next—a clear string of sentences recorded from her hospital bed in which she said, “I saw. I heard. I will not.”

Judge Peterson looked at Bria the way a woman who has seen too much looks at a woman who thinks she’s the first to try a thing. “Probable cause,” she said. “Second-degree assault. Bail set at fifty thousand. No contact order issued.”

My father stood. “Your Honor,” he said, voice crisp. “Our family—”

“Mr. Wilson,” the judge said, “this is not a family. It is a court.”

They led Bria away. She turned and let the mask drop for me and me alone. That look—raw and unvarnished—was worse than the push, because it was honest and had been all along.

Outside, reporters panned for tears. Jillian put her arm around me and took me home.

Part Two

The legal process moved like winter: slow, cold, unhurried by anyone’s impatience. Bria’s lawyer saw the footage and negotiated a plea: probation, mandated therapy, fines, the restraining order carved into paper. My father paid everything but attention. My mother wrote a letter six months later that contained an apology that wasn’t one and then, on the second page, a sentence that might have been: Perhaps we did favor Bria. Perhaps we should have listened to you more. I miss my daughter.

Dr. Stein read it aloud with me in her office. “Not the whole loaf,” she said. “Maybe a slice. You’re allowed to take it and still insist on bread.”

We met in a cafe halfway between our houses once a month. The first time she arrived in pearls. The second time she didn’t. We spoke in weathers rather than events: how to stand on a porch when your house has been a stage; how to hold a granddaughter without making her a promise you cannot keep. I did not forgive her. I also did not keep score. Both are valid strategies. I chose the third: conversation.

Grandma moved in with Jillian, who had the right kind of throw blankets and did not mind moving chairs to make room for machines. She changed her will without fanfare one last time because sometimes consequences belong on paper as well as in people.

I went back to work. My colleagues acted like one body with many hands: someone set Out-of-Office for me; someone sent flowers that did not require water; someone forwarded Bria’s GoFundMe link with the single word gross. I built campaigns and scheduled calls and learned that the part of me that had always tried to please was also very good at making people listen to truth about products and timelines. It was useful there.

At night, when quiet was too loud, I visited the stairwell in my head and rewrote the scene. In some versions she didn’t push. In others she did but then grabbed my wrist. In the truest one, everything happened the way it did and I stood up anyway.

Jillian bought me a small wind chime and hung it by her kitchen window. “So you get to decide when a stairwell makes a noise,” she said, and I loved her for doing a silly thing on purpose.

Once a week I went to see Nurse Marlene with a basket—a loop of gratitude. She waved me off and said she had done her job. “You did more,” I said. “You pressed record when everyone else pressed family.” She said she had two sisters. We both laughed.

One year later I brought the basket one more time—tea, honey, a plant even I couldn’t kill. “You look strong,” she said, and the words landed somewhere I had built for them.

“I feel strong,” I said, surprised to hear it and to find it true.

The town forgot exactly, in the way towns do when something bigger and shinier rolls through. Bria moved to Chicago where her story could start over among strangers. My father did not speak to me. My mother learned how to ask me a question without answering it herself. Grandma passed away two springs later, holding Jillian’s hand and telling us not to buy flowers because we were capable of growing our own.

At the funeral my father stood by the sapphire necklace and said nothing. Jillian held the will and said the words Grandma had put there. After, my mother sat next to me on a bench under an elm and told me about the first time she had seen my father and how Bria was the first person to kick inside her and how she had always been so tired. “I don’t expect forgiveness,” she said.

“I don’t keep it,” I said. “I keep the door.”

She nodded with relief and grief braided together and we watched the light move across the grass the way it moves across the face of a woman who is finally not lying to herself.

Detective Harris sent me a card that said simply, You did it. I sent her a plant because I was on a roll. She laughed and texted a photo two months later of it thriving on her desk. “It only needs light and not lies,” she wrote.

When the anniversary came again, I found myself back in a stairwell—not the hospital’s, but the one in my new building. I climbed, slow and even, feeling the rails under my hands, hearing the soft footprint of my shoes, this time alone and unpushed. On the landing between floors I stopped and looked down and up and said out loud, “I am not clumsy. I am not dramatic. I am not confused.” The building did not answer. It did not need to.

Bria’s restraining order renewed without incident. I did not read about her life because reading about her life had never been good for mine. My father saw me once in a grocery store and put a jar of pickles in his cart with care as if the cap might explode. We nodded at each other like neighbors who keep different kinds of quiet. That was all.

Dr. Stein and I worked on the softer pieces—the voice that tells you to apologize when someone bumps into you, the reflex to make peace, the skill of walking away without throwing a speech over your shoulder.

“Sometimes the families we are born into are rehearsals,” she said one day, handing me a tissue I didn’t need yet. “Sometimes they are drafts with whole scenes struck through. You are allowed to write a new play.”

I thought of Grandma in her chair, letter in her hand, telling me I was not wrong, not dramatic, not forgotten. I thought of Jillian’s back steps and the wind chime. I thought of Tracy’s braid and Marlene’s glance and Detective Harris’s notebook and the judge’s gavel. I thought of my mother’s letter.

On paper, the hospital security camera footage showed a push and a fall. In practice, it showed something else too: the end of a story and the beginning of another. The camera did what cameras do—captured light. The people in that building did the harder thing—believed what they saw, not what they wished they could.

If there is a moral, it is this: tell the truth even if your voice shakes and your ribs protest. Press record when the room says to keep the peace. Plant something under the window where you once waited for footsteps that never brought you what you needed. When someone tells you family will be destroyed by honesty, remember that family built on lies is already rubble.

One evening in late summer I hosted dinner for the people who had stood between me and the black hole my family had been trying to make of my sanity: Jillian, Nurse Marlene, Dr. Stein, my boss, Grandma’s lawyer who had notarized her deposition with tears in her eyes. We ate on Jillian’s porch because it had the right kind of light. We passed food. We told small stories: herbs that lived; patients who walked; campaigns that worked. We said Grandma’s name. We did not say Bria’s.

After they left, I sat with the dishes and the quiet. I thought about stairwells and cameras and push bars and choices. I thought about the way my life had expanded to include my own oxygen. I did not feel dramatic. I felt alive.

Sometimes the proof lives in hard drives and evidence bags. Sometimes it lives in the way you wake up and don’t reach for your phone because the first text you want is yours.

When I finally turned out the porch light, I stood for a moment in the doorway and listened. The house hummed. The night was kind. The stairs inside led up to a bed I had made and would climb into under a quilt someone had stitched with patient hands. No one was at the top with a push. No one was at the bottom whispering I deserved it.

The camera had caught everything that mattered that day. The rest, I get to write.

END!

News

My Husband’s New Wife Demanded Her Share of My Father’s Estate, But My Lawyer Had Other Plans. CH2

My Husband’s New Wife Demanded Her Share of My Father’s Estate, But My Lawyer Had Other Plans Part One…

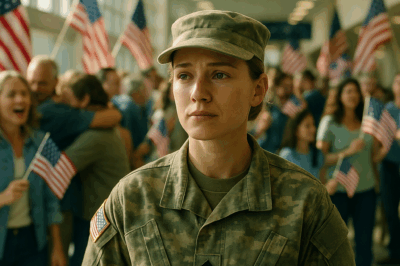

At 1 A.M., My Mom Collapsed at My Door — Dad Hit Her for His Mistress. I Put On My Uniform… CH2

At 1 A.M., My Mom Collapsed at My Door — Dad Hit Her for His Mistress. I Put On My…

I Was Shattered When I Found My Grandma Locked In The Basement While My Family Danced Upstairs… CH2

I Was Shattered When I Found My Grandma Locked In The Basement While My Family Danced Upstairs… Part One…

At the Will Reading, Dad Smirked With His Mistress – But Grandma’s Final Wishes Changed It All . CH2

At the Will Reading, Dad Smirked With His Mistress — But Grandma’s Final Wishes Changed It All Part One…

I Come Back From Afghanistan With One Arm — And My Family Acted Like I Didn’t Exist… CH2

I Come Back From Afghanistan With One Arm — And My Family Acted Like I Didn’t Exist… Part One…

My Dad Skipped My Iraq Homecoming. A Week Later, He Called in Panic. CH2

My Dad Skipped My Iraq Homecoming. A Week Later, He Called in Panic Part One “Your brother’s BBQ is…

End of content

No more pages to load