My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off

Part 1

I was never the daughter they bragged about.

In our house, love didn’t arrive in equal portions—it arrived dressed like applause, and it always stood a little closer to my sister. Amanda was the trophy: tall and blonde with a smile that clicked on like a light switch anytime someone said “Cheese.” She won medals for things I didn’t know were competitions—etiquette luncheons, “most promising” pageant categories, a ribbon for “poise under pressure” after balancing a book on her head while answering questions about community service she never did. The refrigerator was her museum. Report cards edged with gold stars, prints from glossy pageant photographers, a program from the county parade with her name spelled correctly in serif.

My name—Hannah—showed up on chore charts and sticky notes.

When Amanda posed in taffeta, I was asked to take the photo. You’re more creative, Mom would say, passing me the camera like a consolation prize. But it wasn’t creativity she wanted. It was concealment. In pictures I was a blur, a shadow, a pair of elbows. Step back, she’d murmur, and I learned early that stepping back was how our family stayed in frame.

There was one person who didn’t try to crop me out. My grandmother—stormy‑eyed and practical—saw right through the staging. “The world’s full of frames,” she told me once in her kitchen, pressing a silver hair clip into my palm. “Most are too small. Make your own.” Years later, when she was gone and the house no longer smelled like cinnamon and Pond’s cold cream, I would find that clip in a shoebox and think: She is still right.

I left home the first chance I got. Not with fireworks or a slammed door, just a quiet U‑Haul and a handshake from my father who said, “Don’t call unless you need money,” which I took to mean don’t call. I went to a modest college two hours away and earned my degree in the slow, pieced‑together way of girls who work two jobs. I learned how to stretch soups, how to say no to shifts only when I already had two, how to walk home at night with my keys between my fingers and my shoulders high. I learned how to be unremarkable and survive anyway.

Then I learned how to love loudly.

Her name is Josie. She came into the world with a wail that sounded like indignation and relief. The nurse said, “She’s a talker,” and though the nurse meant lung capacity, I took it as prophecy. From the second she arrived, I promised her a different life than mine. Fully loved, fully seen, fully safe. She wasn’t the kind of child magazines write about. She wasn’t thin. She didn’t like bows. She wore mismatched socks with the conviction of a person who has tasted freedom. She built paper cities that spread under our coffee table like declarations. At bedtime she’d ask, “Do stars ever get lonely?” in the same tone other kids asked for another story.

Her eyes were my grandmother’s eyes—storm‑gray, curious as weather.

I never once saw Josie as anything less than remarkable. I never imagined I’d be asked to unsee her.

When she was seven, an invitation arrived like a postcard from a country I’d stopped visiting. My mother, Diana, wanted a family portrait to hang above the fireplace at the estate. “We’re gathering everyone,” the email read, as if we had ever been a “we.” Amanda would be there with her twins. There would be a photographer “who has worked with several notable families.” The tone was part decree, part press release. The kind of tone that assumed compliance.

I stared at the message. We hadn’t been close in years. The last time we visited, Josie spilled juice on a rug and my father looked at her the way a judge looks at a defendant who doesn’t understand the charge. But curiosity is a hinge; it swings you forward when you should stay put. Part of me—small and foolish—wondered whether this photo might be a truce, if not for me then for my child. I sent a brief yes, attached the time I could arrive, and pressed send with the unease of someone who knows exactly how hope burns you and reaches for it anyway.

The morning of the shoot, Josie chose her favorite outfit: a green sweater with elbow patches and a purple skirt that swung like a bell. “Because it’s me,” she said, twirling in our apartment’s narrow hallway. She looked like spring insisting itself into February. I told her she looked beautiful. We took the bus into the better part of town, then walked the last two blocks because the neighborhood felt like it appreciated arrivals that took effort.

My parents’ house had been redone since I last saw it—white on white with glass that dared fingerprints, marble that announced you. It didn’t look like a home; it looked like a magazine spread holding its breath. Amanda’s twins were dressed in identical cream suits, hair slicked into compliance, tiny lapel pins winking like little lies. Amanda waved the way rich people do, with just her fingers, then leaned down to kiss the air near Josie’s head and said, “Well! Look at you,” in a tone that could have meant anything.

My mother wore pearls heavy enough to anchor a boat. My father didn’t offer greeting or coffee or warmth; he offered eyes. They landed on Josie as if she were a candidate for a position he felt the family had no need to fill. I felt my body step a half inch in front of hers before my brain caught up. That was instinct now—shield first, ask later.

We were standing in the broad, echoing foyer when it happened. Mom took my elbow and directed me toward a corner where the photographer was fussing with a tripod. Her voice dropped to a polite whisper sharpened to a blade. “Hannah,” she said, “I think it would be better if Josie sat this one out.”

I blinked. “The… photo?”

“It’s just—the theme is clean and uniform.” She gestured toward Amanda’s twins, who looked like a before‑and‑after ad where nothing had changed. “The boys are dressed identically and Josie’s outfit is… distracting.”

“She’s seven,” I said, my mouth already salt. “She dressed herself. She looks like herself.”

Mom smoothed a nonexistent wrinkle in her cardigan. “She’s just not particularly photogenic, sweetheart. You know how these things last forever.” She didn’t meet my eyes. “We can do a separate picture of the two of you, but not for the main portrait.”

My ears rang like something had struck me, hard and precise. My father, who had drifted near like fog, muttered, “You always make things difficult,” as if this moment were my invention.

Josie, playing with Amanda’s boys nearby, felt the shift the way animals feel storms. She came to me and tugged on my sleeve. “Mommy, are we still taking pictures?”

I knelt so we were eye‑level, swallowing a hurricane. There are a hundred speeches a mother can make about dignity and harm and not letting the people who hurt you decide your narrative. There is only one thing a mother can do when her child’s heart is on a table. “Not today, baby,” I said. “We’re going home.”

We didn’t scream. We didn’t demand. We didn’t perform the kind of drama that makes people pick teams. We just walked—small, bruised, intact—back to the car. Josie didn’t ask why. She sat in the backseat with her hands knotted in her purple skirt and looked out the window at all the other houses where other families lived. Her light, my brilliant girl’s light, flickered.

I didn’t sleep that night. I sat in the dark and watched her breathe, her fingers curled around the stuffed turtle my grandmother gave me decades ago. I cried—not because of the photo, but because I recognized the weight settling in her small chest. I had carried it most of my life. The voice that says, You don’t belong. You’re not enough. Your joy doesn’t match the room. I realized then that my parents hadn’t just mistreated me; they were prepared to pass that inheritance to my child.

The next morning, I blocked their numbers. No speeches. No second chances. No invitations for tidy apologies that rearrange nothing. They made their choice within earshot of my daughter. I made mine within arm’s reach of her.

We built a new perimeter—one stitched from library cards and neighborhood parks, the Saturday farmers market where the flower vendor tucked fallen petals into Josie’s hair, the laundromat where people shared dryer sheets and gossip. I taped butcher paper to our living room wall and told Josie, “Make a mess big enough to need new rules.”

For a while, she seemed okay. Kids are experts at bounce. She still wore wild outfits, still built cities from cereal boxes and painter’s tape, but small changes gathered like dust: she avoided mirrors unless she was making faces; she stopped showing teeth when I took pictures; one day, walking home from school under a sky trying to decide if it was rain or blue, she asked, “Mom, do you think I’m… distracting?”

That word. Like someone had slipped a shard of glass into her pocket.

That night, in a fit of defiance and faith, I typed “children’s art programs city” into my phone and signed her up for a museum class I couldn’t quite afford. It wasn’t about talent; it was about permission. I wanted her surrounded by adults who clapped for difference and kids who understood that the best color is the one you invent.

On the first day, Josie wore the green sweater my mother said clashed with “the aesthetic.” The classroom smelled like washable paint and hope. The teacher, a woman who introduced herself as Miss Ray, crouched to Josie’s height and said, “That color makes your eyes look like magic. Did you know that?” Josie beamed. If you are lucky, you remember the handful of sentences that shift the ground under your feet. That was one.

Miss Ray ran the class like a loosely held secret. She didn’t tell the kids what to draw. She told them to pick a feeling, then hand it a brush. She taped up Jackson Pollock prints and Frida Kahlo self‑portraits and said, “Sometimes the only way to tell the truth is to paint it louder than people can talk.” Josie’s hands trembled at first. Then they learned the shape of her own courage.

Three weeks in, Miss Ray pulled me aside. “Your daughter’s mind,” she said, eyes bright. “It’s electric. She paints emotion like someone three times her age. I hope you don’t mind—I submitted one of her pieces to the Young Eyes competition. It’s statewide.”

“You did what?” I asked, and then I laughed because the question felt silly in my mouth. She grinned. “I couldn’t help it. I’ve been doing this a long time. Josie’s special.”

The painting she chose was an abstract swirl of colors—greens and purples and a smear of gray that moved like weather across the page. In the center, Josie had placed a rectangle, stark and white, with a ribbon of color spilling out of it like escape. She titled it, How It Feels to Be Left Out of a Picture. When I asked her why, she shrugged and said, “Because sometimes people say you don’t fit, but really their frame is wrong.”

Two weeks later, an email arrived while I was eating supermarket sushi at the kitchen counter. “We are thrilled to inform you that your child’s work has been selected as the grand prize winner for Young Eyes,” it read. I set the phone on the counter and walked around the room once so my body could catch up to the words. Josie was in the tub making a mermaid kingdom out of plastic cups. I knelt on the bathmat and told her, and she squealed so loud our upstairs neighbor texted, “Everything okay?” with three question marks.

The museum hung the painting in its front gallery with soft lights that made the colors glow like they were telling secrets to each other. Beneath it they printed the title and—at Miss Ray’s urging—a quote from Josie: Sometimes people say you don’t fit in their photo. That just means they can’t see the whole picture.

The local paper ran a small feature with a photo of Josie standing in front of her work, chin high, hair unbrushed in the way of children who have better things to do than look perfect. The article didn’t name names. It didn’t need to. The shape of the story did the work.

That’s when the calls started. Unknown numbers. Then a cousin I hadn’t spoken to in years. Then Amanda, whose texts always sounded like she was dictating through clenched teeth. Sorry about the mix‑up at the photo shoot. You know how Mom is. I stared at the screen. My thumb hovered. I typed: No, I know how I am. And I know who my child is. Then I deleted it. Then I typed: There wasn’t a mix‑up. There was a decision. Then I deleted that, too. In the end, I sent nothing. Silence can be a full sentence.

Three days later, the museum called. “We’re hosting a live showcase for the Young Eyes finalists,” the director said. “We’d love for Josie to speak about her painting—nothing scripted. Just a few words about what she made and why.”

I almost said no. She was seven. Seven is for shoelaces and spelling lists and making snow angels in pile‑driver form. Seven is not for podiums and microphones and rooms full of adults leaning forward like parched things. But when I told Josie, her eyes lit the way hallways do at school when the afternoon sun sneaks in. “Can I wear my green sweater?” she asked, hand already stroking the sleeve. “You can wear anything you want,” I said, and meant: You can be anything you are.

On the night of the event, the museum’s mezzanine swelled with families and board members and the kind of donors whose laughter sounds like ice in a glass. The city turned gold behind the long window, all the office buildings blinking at once like the skyline had an idea. I pinned my grandmother’s silver clip in Josie’s hair, the way my grandmother once pinned it in mine. Josie looked in the mirror and whispered, “I hope I don’t look too distracting.”

I dropped to my knees and took her hands. “Baby,” I said, sure as stone, “you’re not a distraction. You’re the art.”

We arrived just before sunset. Miss Ray waved from across the room, hands flecked with permanent color. Josie’s painting had been moved to the center of the wall, haloed in a pool of warm light that made the greens deeper and the gray more beautiful than sadness. Her quote sat beneath in bold type: Sometimes people say you don’t fit in their photo. That just means they can’t see the whole picture. —Josie M.

We were nobody there and everybody wanted to say hello. A teenager told Josie, “I feel like that rectangle a lot.” An older man with paint on his knuckles said, “You made my favorite feeling look like a place.” I breathed it in—the rightness of a room where my child belonged because she had turned pain into color and the world, for once, knew what to do with it.

Then I saw them.

Near the back, half‑hidden behind a column as if pillars could absolve, stood my parents. My mother in a beige wrap, pearl studs small and obedient. My father in a pressed collar, mouth a line broken only by the act of holding in words. Amanda was with them, her posture performing neutrality, her eyes darting the way people’s eyes dart when they are studying exits.

I hadn’t told them. I hadn’t told anyone in that part of the family. Clearly someone else had. The sight of them sent a half‑remembered panic through my body, the kind that doesn’t ask permission to enter. But fear can be a familiar thing you choose not to pick up. I looked at Josie, who was standing in front of her painting with a note card in her small hand, lips moving as she practiced something only she could hear. I stood a little taller.

Miss Ray touched Josie’s shoulder. The museum director tapped the mic and asked the room to gather close. People shuffled in that polite way crowds do, steps careful not to step on anything fragile. He introduced the program, then the prize, then the child who had made the picture that made strangers cry.

“Josie,” he said, with the reverence of someone who knows a moment when he sees it, “would you like to tell us about your painting?”

She walked toward the podium that was almost too tall and stood on her tiptoes. Miss Ray lowered the mic until it hovered like a hummingbird at Josie’s mouth.

Josie looked out at the room.

Her eyes found me first.

Then they moved beyond me.

They found my parents.

She took a breath.

The room hushed.

—To be continued in Part 2.

My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off

Part 2

Josie leaned toward the microphone. Her sneakers didn’t quite touch the floor, so she balanced on her toes and steadied herself with both hands on the edge of the podium. When she spoke, her voice wasn’t loud, but it carried—clear, small, certain.

“This is my painting,” she said. “I made it because sometimes people don’t want you in their picture, but that doesn’t mean you’re not beautiful. It means they don’t see right.”

A hush unfurled—first the polite silence of audiences, then the deeper quiet of people receiving something true. She glanced down at her note card, but didn’t use it. She lifted her chin instead, scanning the room with those storm‑gray eyes that had once convinced my grandmother the world could still be surprised.

“I made this the day someone told my mommy I wasn’t pretty enough to be in the family photo,” she continued. “I heard it. I didn’t cry. I just made this instead.” She pointed at the rectangle in the center. “That white box is the frame people give you. The colors are what you really are. Sometimes you have to spill out.”

For a heartbeat, nobody moved. Then the sound gathered like weather—hands finding each other, feet standing, throats clearing. Applause rolled forward from the back row to the front, not the tidy kind people use when they’re waiting for dessert, but the messy, grateful kind that stands up because sitting feels wrong. A teen in a denim jacket cupped his hands to shout “Go, Josie!” and then cried into his sleeve as if embarrassed by his own courage. Miss Ray wiped her eyes openly. The museum director pressed his palm to his chest in a gesture I would later, in private, mimic and understand.

I didn’t turn to look at my parents. I didn’t need to. I felt their silence like a cold draft. In my peripheral vision, I saw my mother’s hand drop from its perch at her throat. My father’s jaw tightened and then loosed, as if reconsidering the work it wanted to do in the world. Amanda clasped her clutch so tightly the knuckles went white, then released it to adjust a nonexistent hair.

When the clapping finally softened, Josie said thank you into the microphone, then bobbed an awkward, perfect bow. She walked back to me like someone crossing a creek on stones—careful, light, a little thrilled with herself. I crouched and gathered her into my arms, smelling tempera paint and kid‑shampoo and the warm salt of a girl who had chosen to make a picture instead of a wound.

“You were brave,” I whispered into her hair.

“I was just honest,” she said, and pulled back to check my face, as if courage couldn’t quite be courage unless it had a witness.

The rest of the evening moved like a dream you remember in detail. People we didn’t know formed a small line to tell Josie what her painting had moved in them. A woman with a rainbow pin on her backpack said, “I’ve been that rectangle my whole life”; a man with a white beard said, “Some frames are cages”; a boy in Velcro shoes asked if the museum served ice cream, and when we said no, he looked at his mother with betrayal and she said, “We’ll fix that.”

The museum director found us in the gentle chaos. He had a reporter trailing him—hair sprayed into submission, smile oiled for television. “Hannah,” he said, “there’s someone here from the Today show. They saw the paper and the clip we posted. Would you be open to a short segment? Nothing invasive. Just—this story is… it’s important.”

I felt my body do that complicated thing it does when past and present collide: a tightening and an opening at once. “She’s seven,” I said, more to myself than to him.

“She’s also ready,” Miss Ray said from my side, a hand light on my arm. “And you can say no at any time. We keep the frame yours.”

I knelt and asked the only person whose answer mattered. “What do you think, Bug? Would you like to talk about your painting on TV?”

Josie considered it with the gravity of a judge and the bounce of a child whose favorite word is yes. “Can I wear my green sweater?” she asked.

“You can wear anything you want,” I said. The museum director’s smile turned real.

Out of the corner of my eye, I saw movement: my mother, stepping forward with a practiced smile that had charmed donors and deceived me in equal measure. She reached for Josie’s shoulder as if nothing in the world needed acknowledging.

“Darling,” she said, voice honeyed and high, “what a big night! We’re all so proud.”

I pivoted. Something in me—the old girl who was told to step back—rose hard, then sat down. But the woman I had become stayed standing. I placed myself between her hand and my child with the easy, unapologetic grace of a revolving door that decides to stop revolving. “We’re busy,” I said. I didn’t put malice in it. I didn’t need to. Boundaries, I had learned, can be delivered at room temperature.

She blinked. “Hannah, really. Don’t make a scene.”

“I’m preventing one,” I answered, and turned away. My father hovered a step behind her, hands in pockets, posture built for scolding, but he said nothing. Amanda gave me a look that tried to be sympathetic and landed as practice. We walked toward the reporter and kept walking all the way through the rest of our night.

The segment filmed a week later in a studio with lights bright enough to feel like weather. Josie sat in a chair too tall for her legs, green sweater on, silver hair clip winking like a secret, Miss Ray’s paint‑splattered smock in the front row of the small audience, me just off camera trying to breathe steadily enough that she could borrow the rhythm.

The host asked gentle questions, for which I will be grateful for the rest of my life. “What did you paint?” “How did it feel?” “What would you say to kids who feel left out of the picture?” Josie answered without pretense. “Sometimes grown‑ups don’t understand how words stay in your heart,” she said. “But you can make art out of it. That’s what I did.”

The clip aired the next morning. The world did the thing it does when it remembers how to be beautiful—retweets and texts and a hundred emails from strangers who sounded like friends. Teachers asked for permission to print the quote and tape it over classroom doors. A mother wrote to say her kid wore the green shirt everyone mocked to school and came home saying, “I’m the art.” A soldier stationed overseas wrote, “I was cut out of a lot of pictures growing up. Please tell Josie I see the whole thing now.” We put the messages in a folder labeled Frame‑Builders and promised ourselves we would read them on rainy days.

I changed nothing about our phone plan, but somehow my parents found a way to reach me anyway—through relatives with no sense of decency, through acquaintances with appetites for drama, through numbers that rang with the persistence of debts. Amanda texted: Mom is furious. She says you embarrassed her publicly. I stared at the screen for a long moment, then typed back, steady: No. She embarrassed herself. We just refused to blur the photo. I didn’t send it. I never sent the perfect sentences. I learned to prefer the quiet ones that ended in action.

The museum gifted us a framed print of How It Feels to Be Left Out of a Picture. We hung it above our couch, a place of honor achieved not by marble but by the daily holiness of Netflix and naps. The rectangle glowed white, the colors refused to apologize. Every morning, when Josie ate her toast with too much jam and kicked her heels against the chair rung, she looked up and saw what she had done with hurt. Her shoulders squared, small and significant.

A month later came a letter. No return address, just our names typed neatly—my mother’s handwriting replaced by the kind of script you choose when you want to look official. Inside: a short note.

We were wrong about you, about her, about everything. We’re sorry. If you ever want to talk, we’ll listen now.

I read it once at the kitchen counter, once sitting on the floor with my back against the cabinets, once standing with the letter pressed to the refrigerator door as if cold could make it truer. Then I put it in the drawer with warranty cards and the orphan keys that open nothing in our current life.

People love the redemption arc. They want the scene where the prodigal mother cries, and the daughter softens, and a new family photo is taken with everyone arranged by grace instead of symmetry. I love redemption, too, but not as theater. I believe in repair that begins with changed behavior, not rewritten lines. I believe in apologies that are cheques you cash in daily actions. I believe in keeping doors shut when the room behind them no longer fits the life you’re building.

We didn’t call. We didn’t write. We went to the farmers market on Saturdays and let the flower vendor keep slipping petals into Josie’s hair until her head looked crowned on purpose. We took a Sunday drive to my grandmother’s old neighborhood so I could tell Josie stories that didn’t need villains to feel full. We learned to bake a lopsided cake without arguing about frosting. We had dinner with Miss Ray once a month, a ritual that turned into something like family: a teacher who saw my girl and a mother who had waited her whole life to be seen, passing bowls of pasta and talking about color theory as if it were a language we’d always spoken.

At school, Mrs. Alvarez asked if Josie might lead a mini art talk for the second graders. “Ten minutes,” she said, “about how to turn a hard feeling into a picture.” Josie practiced on our living room floor with stuffed animals lined shoulder to shoulder. She told the bear that sometimes frames are too small and told the giraffe that it’s okay to be taller than your picture. The giraffe promised to try.

One afternoon in the spring, I took her to a real photographer’s studio. Not because we were trying to recreate anything or prove a point, but because Josie looked at me while brushing her hair and said, “Can we make a photo for us?” The studio smelled like dust and new backdrops. The photographer—a woman with laugh lines and a voice like a porch—asked, “What’s our vibe?” and Josie said, “Us.” She wore the green sweater. I wore jeans with paint on them because that is who I had become. We danced while the shutter clicked. We stood still for one frame because sometimes stillness is the point. We made faces, then made a promise: pictures in our house would be documents, not demands.

The print arrived a week later. We taped it beside the painting, not above or below—beside, equal weight. In the photo, our heads lean together, the world behind us slightly blurred, our bodies decidedly in frame. Sometimes, passing on my way to brush my teeth, I stop and put my hand against the glass, palm against palm, as if blessing the girls inside who kept choosing each other in rooms that wanted them to choose otherwise.

People asked, as they do, whether I ever thought I would regret cutting ties. I told the truth: some nights I missed the idea of parents the way I miss the idea of a beach house—possible for other people, pleasant to imagine in winter. But I did not miss the actual house, the actual weather, the actual price. On the days the ache pressed harder, I went to the drawer and reread the letter and tried to imagine what “We’ll listen now” would look like if it were a calendar instead of a sentence. I rarely got far.

The world kept being the world—an uneven mix of the kind and the careless. Strangers came up to us in grocery stores because they recognized Josie’s sweater and said, “You made me braver last week,” and I watched my daughter learn how to receive praise without apologizing for needing it. A girl in the park told her, “My aunt cut me out of a picture once,” and Josie said, “Do you want to draw with chalk?” and they did, side by side, two rectangles with colors spilling out across the sidewalk until the rain came and made something new of it.

Then, in early summer, the museum hosted a small reunion for the Young Eyes finalists. The kids, who had become a tribe forged by paint and applause, ran the halls like they owned the place—and for the afternoon, they did. Parents traded recipes and stories. Miss Ray hugged everyone, even the teen who pretended to hate hugs. The museum director made a short speech about the power of small hands making big statements. I stood near the punch bowl and felt grateful right down to the bone.

My parents didn’t come. The absence felt intentional in a way that wasn’t cruel, just factual. I realized as I watched Josie lift a paper cup to toast with her friends that my parents’ silence had changed shape. It was no longer a wall against which I threw myself; it was a geography I had chosen not to visit. You can love a country and never go back. You can mourn the map and still be happy where you live.

On the walk home, we cut through the park and sat on a bench to split a lukewarm soft pretzel. Josie swung her legs and asked, “Do you think frames ever get bigger?”

“Sometimes,” I said. “But sometimes you outgrow them so much you don’t notice whether they change.”

She nodded, thoughtful in the way of kids who are always assembling a private philosophy. “Miss Ray says when you make art, you make a room for other people, too.”

“She’s right,” I said. “That’s what you did.”

“What if the people who hurt you want to come in?” she asked.

I took a breath. I don’t memorize speeches for these moments. I make promises. “Then you decide whether the room is for you or for teaching and whether you have help to keep it safe. You decide if it’s today or another day or never. You decide, baby. Not them.”

She leaned into me and rested her head against my shoulder in that spontaneous, unbothered way that will end sooner than I want it to. “Okay,” she said. “I’m good at deciding.”

I kissed the top of her head. “You are.”

That night, after she fell asleep, I took the letter from the drawer and read it again. I didn’t feel anger, not exactly. I felt the odd, clean ache of understanding: sometimes people hear you only after the world does. Sometimes people change when the cost of not changing is public. Sometimes that’s the best they can do. It’s not enough for my child. It is, however, information. I slid the letter back and closed the drawer softly, the way you do when someone you once loved is sleeping in a room you no longer share.

A year later—twelve busy, ordinary months of homework and shoe sizes and paint‑stained Saturdays—the museum mounted a small show of alumni. They asked each kid to submit one new piece and to bring a photo of themselves they loved. I watched parents kneel in hallways to coax old prints out of frames. I watched toddlers smear crackers into their hair and make friends with guardrails. I watched my daughter hang a new canvas beside her old one: a bright, dizzy storm titled Whole. The photo she chose to pair with it was ours—the one from the studio, green sweater and silver clip, me in jeans, heads leaning, our two bodies in frame like a sentence that had found its subject and verb and finally, finally, the right punctuation.

At the reception, a woman I didn’t know introduced herself quietly. “I’m a therapist,” she said. “I show your daughter’s painting to parents sometimes. It helps.”

I choked on gratitude. “Thank you,” I managed. “For putting it to good use.”

She nodded toward Josie, across the room, explaining to a younger kid why the green she mixed needed just the tiniest bit of blue. “She changed a room she never should have had to stand in,” the woman said. “That will echo.”

It already had. In our living room, in our block, in the inbox labeled Frame‑Builders, in the way my daughter looked at herself when she caught her reflection unawares. It echoed in my own body, too, a lower frequency I only felt when the house was quiet: I had kept my promise. Fully loved, fully seen, fully safe. Not perfectly, not without mistakes—no mother, no person, no canvas is without a stray line—but faithfully, stubbornly, with two feet planted and both hands on the edges of the life we were making.

On our way out, we passed a wall where the museum had set up a community project: a giant sheet of paper with an outline of a frame in the center and markers in every color. Above it, a sign: What belongs in your picture? People had written words and drawn shapes and taped on photographs. Josie took a marker and wrote, in letters that weren’t entirely straight, Me and the people who clap when I’m brave. Then she took my marker hand and wrote below hers, smaller, Us.

We stood back and looked. The frame was overflowing—colors spilling, edges defied. The rectangle no longer had the last word. If you squinted, you could mistake it for a map: not of where we had been pushed, but of where we had chosen to go.

In the car, as we buckled, Josie said, “Can we take a photo when we get home?”

“Of course,” I said. “What’s the occasion?”

She shrugged. “We’re here. That’s an occasion.”

We set the camera on a stack of cookbooks and propped it with the salt shaker. We didn’t stage the couch or hide the laundry basket. We didn’t fix our hair or tuck in our shirts. We sat, pressed our shoulders together, and let the timer flash. In the photo, I can see the lamp we never got around to replacing and the plant we kept forgetting to water and the painting glowing over our heads and two faces—one small, one tired; one storm‑eyed, one tear‑rimmed—looking at the lens like a future we were finally, fiercely, allowed to imagine.

We printed it and taped it up beside the others. I wrote the date on the corner. The next morning, Josie added a green sticker shaped like a star. She said, “Now everyone knows where to look.”

We don’t speak of the portrait that never was. We don’t rehearse the insult. We built a life that makes rehearsals unnecessary. The door to that old house remains closed, not in anger but in clarity. When people ask about grandparents at school events, I say, “We have a village,” and I list Miss Ray and Mrs. Alvarez and the neighbors who let Josie pick cherry tomatoes off their vines. Family is who claps when you’re brave and who sits with you when you’re not. Family is who keeps you in the picture when the room gets smaller.

Once, months later, on a gray afternoon when the sky matched our eyes, Josie crawled into my lap with a book. “Mom?” she asked, as if she knew she was stepping on a tender place but couldn’t help it. “Do you think they’ll ever be different?”

“I think they might be,” I said, surprising us both with the truth of it. “But we don’t have to be the ones who check.”

She nodded, satisfied. “Okay.” Then she opened the book and began to read aloud, her voice steady as a metronome, each word finding its place in the sentence like a person finding their place in the frame.

In time, the world will forget the segment and the shares and the way a small gallery felt like a revolution. That’s fine. What we keep will be quieter: the sound of applause rising when a seven‑year‑old told the truth without flinching; the feel of a green sweater under my palm as we left the museum that first night; the weight of a silver hair clip in my hand, a little cold, a little bright, like legacy should be. What remains on our wall is a painting and a photograph and a dozen smudges from fingers that always find the glass.

The girl they called “distracting,” “not photogenic,” “not a match,” turned out to be the most radiant person in the room—the room she remade simply by refusing to disappear. The mother who once stood behind the camera learned to step into the picture and stay.

We didn’t need their frame.

We learned to build our own.

And in this one—ours—the colors spill forever.

The End

News

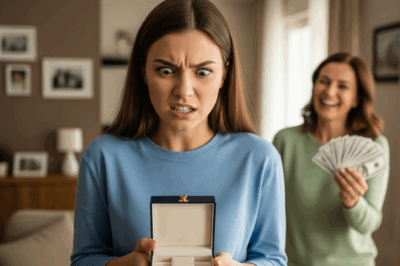

Mom Sold My Priceless Heirloom, Laughing, You’ll Thank Me Later! I Made Sure She’d Regret It Forever. CH2

Mom Sold My Priceless Heirloom, Laughing, You’ll Thank Me Later! I Made Sure She’d Regret It Forever Part One The…

Man Wouldn’t Let An Officer Sit In Coach, Then She Slips Him A Note. You Won’t Believe What’s Inside. CH2

Man Wouldn’t Let An Officer Sit In Coach, Then She Slips Him A Note. You Won’t Believe What’s Inside Part…

After 9 Years, Couple Opens Wedding Gift Aunt Told Them Not To Open. CH2

Part 1 They married in late spring, on a day that seemed made of warm light and second chances. Kathy…

My Parents Cut My Hair While I Slept So I’d Look Less Pretty at My Sisters Wedding So I Took Revenge. CH2

My Parents Cut My Hair While I Slept So I’d Look Less Pretty at My Sister’s Wedding So I Took…

Mother-In-Law Threw Away My Late Mom’s Jewelry Laughing So I Taught Her a Lesson She’ll Never Forget. CH2

Mother-In-Law Threw Away My Late Mom’s Jewelry Laughing So I Taught Her a Lesson She’ll Never Forget Part One I…

COP Officer Strangles Woman And Accuses Her Of Car Theft, He Is Sentenced To Prison Minutes Later. CH2

COP Officer Strangles Woman And Accuses Her Of Car Theft, He Is Sentenced To Prison Minutes Later Part One You…

End of content

No more pages to load