My parents sued to evict me so my sister could own her “First home.” In court, my 7-year-old asked the judge, “Can I show you something mom doesn’t know?” The judge nodded. She held up her tablet. Pressed play… but when it started…

Part I — The House I Built After the Life I Lost

I never imagined betrayal would sound like a gavel.

Three years earlier, after the divorce, I came back to the neighborhood with nothing elegant to say about it. I just needed a place where silence didn’t echo. The craftsman on Hawthorne had been sagging into itself—siding peeled like old paint chips in a jar, porch rail loose, windows clouded the way grief fogs a face. I ran my hand over the sunburned door, felt a splinter slide into my thumb, and said, “Yeah. You and me both.”

I tore out old carpet and found fir floors beneath that looked like they’d been waiting for someone who believed in second chances. I sanded until my arms hummed, stained them the color of coffee that sat too long. I rebuilt the porch. Rehung the kitchen cabinets. The first night I slept there, sawdust still trapped in my hairline, Emma curled around my arm and whispered, “This house smells like pencils.” I laughed in the dark. “Good. That means it’s learning.”

My parents visited with casseroles and commentary. My mother ran a fingertip over a window mullion and said, “Lily always loved natural light.” My father helped me file my taxes and left drafts on my counter, highlighted paragraphs about deductions like he was teaching a class I had failed. The appraiser called “to update local listings” and asked questions that were both routine and just a hair too curious. I told myself I was paranoid. I wasn’t.

Emma spent weekends drawing at the dining table while I pried trim from walls, her tablet propped beside a paper cup of markers. She is seven in the way some people are sixty: quieter than you think they should be, seeing more than you wish they would. When the first daffodils crawled up the strip of dirt by the front steps, she stood there, hands in the pockets of her sweatshirt, and reported, “They’re trying their best.” We watered them like they were and they did.

My sister, Lily, came by with her fiancé, Ryan. She called the house “cute,” the way a realtor praises a room they wish were larger. “We want to be nearby,” she said, eyes performing brightness. “Close to Mom and Dad. It would be poetic if this stayed in the family, right?” My mother looked at me when she said poetic as if it were a word she had practiced to make it sound casual.

The first time she said it, I laughed. She didn’t.

That was when I started watching in the way you do when your body knows before your mind signs the paperwork. The drafts my father left on my counter started to mention “family trust” in the margins. The appraiser called again. My mother asked about my mortgage and said, “It must be nice to have help.” I didn’t fight. I planned.

I recorded everything. Not because I like the sound of my own voice but because the people I loved had started using theirs like rope. Every conversation on the porch with my father that started with “Proud of you, son,” and ended with “It would be smoother if Lily…” Every kitchen-table chat with my mother that started with a casserole and ended with “This house is bigger than your feelings.” Every time Lily set her ring on the counter and said, “We need more rooms. For the photos.”

I was the polite one. It used to be a compliment. Sometimes it’s a diagnosis.

Part II — The Case Number and the Case I Built

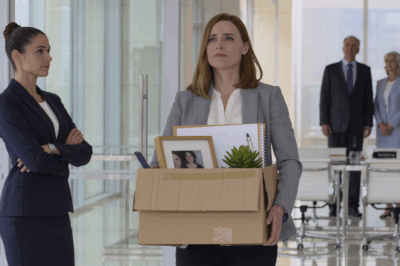

The day the summons arrived, I was sanding the banister spindles so the paint would hold and the future could grip without splinters. The envelope was the color of bad news. Inside, words stacked like accusation: Anderson vs. Anderson. Petition to quiet title. Alleged misuse of family trust. Relief sought: eviction and transfer of deed to the family’s intended heir, Lily Anderson.

My father called thirty minutes later, voice dipped in sorrow. “You understand, don’t you? It’s what’s best for everyone.”

“Everyone?” I asked.

“Lily’s wedding is in the fall. It would be—” he groped for the word my mother had taught him—“poetic.”

“I bought this house,” I said. “With my settlement and a bank loan. There was no trust.”

“Verbal agreements count,” he said, as if the law were a dinner conversation he could steer.

I didn’t argue. I let him talk. I let him admit on a recorded line that there had been no trust at closing, that he “intended” to “make it right for Lily” after the fact, that the appraiser “owed him a favor,” that I “fold when family insists, you always did.” When he hung up, I saved the file to three places and labelled it something I wouldn’t have to listen to again.

That night, at the dining table, Emma tapped her tablet like a tiny stenographer. “Grandma said we’ll have to move soon,” she murmured, voice as casual as weather. “She said this is Aunt Lily’s real house now.”

“She said that?” I tried to sound like a man asking for proof of something incredible, not like a father absorbing something inevitable.

Emma nodded. “I recorded it. Want to hear?”

I wanted to breathe. I wanted to wrap the world in bubble wrap and label it fragile and keep it on a top shelf my parents couldn’t reach. “Later,” I said. “Only if you want to.”

She shrugged. “I want to help.”

My lawyer, Ms. Perez, sat across from me the next morning drinking coffee too black to be polite. “They filed a trust claim,” she said. “Unsigned drafts. No corpus. No funding. They’ll argue verbal intent. Judges do not love verbal intent when it comes to property because people say weird things at Thanksgiving.”

“What if they bring witnesses?” I asked.

“They’ll bring each other,” she said. “You’ll bring receipts. Judges love receipts.”

“What if it isn’t enough?”

She smiled in a way that wasn’t unkind. “It will be. And if it isn’t, we appeal. But I’ve seen this play. You don’t win it with speeches. You win it with paper. Or—” she tapped her temple—“tape.”

The night before court, I sat on the steps after Emma fell asleep, the porch light a halo that made the moths think they were invited. I touched the rail I’d planed smooth, the post I’d reset plumb, the knot in the wood shaped like an eye that watched the street. I thought about all the things we inherit that we never signed for—the way my father’s voice turns iron when he’s wrong, the way my mother uses sorry as a lubricant, the way Lily learned that if she wanted something she should make it sound like a favor.

“Dad?” Emma whispered behind me. She padded out in her socks and sat on the step, tablet in her lap like a shield. “I’m nervous.”

“Me too,” I said. “That means we’re real.”

“Can I show the judge something mom doesn’t know?” she asked, a sentence that reached across my entire life and tied a knot at the end of it.

I took a breath that reached my toes. “If you want to.”

“I do.”

Part III — The Tablet, the Tape, and the Thunder

The courthouse smelled like paper trying to become power. The judge was an older woman whose gaze looked like it could sand a lie down to splinters. “This court will now hear case number 5473, Anderson versus Anderson,” the clerk read, and the gavel knocked the air obedient.

My parents didn’t meet my eyes. My father’s tie was perfect. My mother’s mouth was the kind that smiles without moving. Lily looked like a victim in a photograph of herself, tears in the right places.

Their lawyer stood, a man who wore his suit like a certificate. “Your honor, Mr. Anderson used his parents’ trust fund to purchase this property. It was always intended for his sister. We request it be returned to its rightful owner.”

“What proof do you have of this trust fund?” the judge asked.

My father slid a folder across like he was offering a dessert menu. The judge flipped, paused, closed it. “These are unsigned drafts.”

“Well,” my father said, tripping on his own confidence, “the documents were verbal agreements.”

“Verbal,” she repeated, and let the word sit in the air like a fly that didn’t fear your hand.

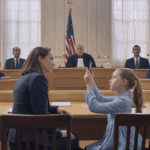

Ms. Perez rose. “Your honor, before our defense, my client’s daughter has asked to show the court something. She’s seven, but we believe it’s relevant.”

The judge’s eyebrow climbed, then settled. “Proceed.”

Emma walked up, small footsteps swallowed by the carpet, tablet clutched like a thing she had built herself. She looked at the judge, not at me. “Can I show you something mom doesn’t know?” she asked, because children tell the truth with prefaces that make it harder to stop them.

The judge’s mouth softened. “Go ahead.”

Emma pressed play.

My mother’s voice filled the room as if she’d been standing on the counsel table. “Don’t worry, Lily. Once your brother’s gone, we’ll tell him it’s for his own good. He never appreciated what we did for him anyway.”

A beat.

My father’s voice followed, stripped of its courtroom suit. “He’ll fold. He always does.”

Lily’s laugh was clear and bright and bloodless. “Good. I want the house before the wedding. It photographs better.”

Silence in a courtroom is different than silence anywhere else. It’s not the absence of noise; it’s the presence of judgment.

“This was recorded in your home, Mr. Anderson?” the judge asked, looking at me as if she already knew the answer and wanted to see if I could say it.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. “My daughter recorded it without me knowing. We submitted the unedited file with metadata and timestamp.”

She nodded the way a person nods when their spine agrees with their mind. “Then I’ve heard enough.” The gavel came down like thunder. “Case dismissed. Property remains in Mr. Anderson’s ownership. Further, this matter is referred to family court for potential fraud investigation.”

My parents didn’t move. Lily began to cry, not the kind that cleans you, the kind that expects an audience to assist. Ms. Perez squeezed my shoulder once and let go like a person who respects gravity.

Emma tucked her tablet against her chest. I knelt. “You did perfect,” I whispered, and then understood the strangeness of teaching a child that perfect sometimes means brave.

My father finally spoke on the way out, voice reassembled. “You think you’ve won?”

I looked him in the eye the way men who taught me not to do that hate. “No,” I said. “I proved you lost.”

We drove home past the oak that drops acorns like a kid drops change, past the mailboxes leaning like old men in conversation, past the life I’d rebuilt plank by plank. The house stood with its shoulders squared like a person who’s been waiting at a bus stop for a bus that finally arrived.

The quiet that night was different. Not empty. Clear.

Part IV — Aftershocks and Blueprints

The referral landed hard. Family court called. Fraud investigates slowly because it prefers paper to theater. The property appraiser who had called me “to update listings” called his attorney instead. The unsigned drafts moved from my father’s printer to an evidence envelope. Lily’s wedding photos were taken against another house’s light. My parents’ lawyer sent a letter that said, without admitting fault, that “misunderstandings had occurred in good faith.” It read like a press release about a hurricane.

My mother left two voicemails a week for a month. They began with “We miss Emma,” and ended with “You’ll feel bad when we’re gone.” I saved them for a week, then deleted them on a morning when the coffee tasted like relief. I wrote a boundary and taped it to the inside of my mind: No one speaks to my daughter about where she lives unless they pay the mortgage with respect.

I told Emma’s mom—my ex—everything, because co-parenting is a house that falls if you pretend it’s built on anything other than truth. She listened, jaw tight, then exhaled a sigh so old it might have been mine. “Emma okay?” she asked.

“She’s… more okay than me,” I said. “Which is a problem I am lucky to have.”

We found a therapist who didn’t overuse the word “journey.” Emma drew pictures of houses with eyebrows over the windows and a smile under the porch, and named them feelings I could understand. The therapist gave us conversations that didn’t shout. He gave me a new sentence: “I can’t control what my parents do, but I can control whether they can do it through my child.”

Lily texted a month later. No apology, just a link to a listing: a new build across town with a staircase that looked like it had been designed for the dress she’d wanted. “Just thought you’d like to know,” she wrote. “We found something that photographs fine.”

I typed a reply three times, then closed my phone and went outside and replaced a fence picket that had split itself from weather. Sometimes the thing you want to say is a nail gun.

On the first anniversary of the court date, Ms. Perez came by for coffee. She walked through the house, hand on chair backs like she was trying to learn a language through touch. “It feels like you live here,” she said.

“I do,” I said.

She smiled. “Not everyone who wins gets to say that.”

Neighbors whose names I had learned finally stopped calling me “the son who got sued” and started calling me “that guy with the good porch light.” I invited the block over for a cookout and grilled like a person who had decided hospitality wasn’t a strategy but a way of inhabiting a place. I watched Emma teach two kids from up the street how to beat her at mancala and fell in love with the house again for being back the simple thing it had earned the right to be.

Family court moved how it moves—through calendars, not headlines. The appraiser lost a license for a while. My father was “admonished” in words that sounded like the scolding he used to save for me when I forgot to rake. Lily received something between a stern look and a future without access to the trust she had tried to mint out of thin air. My mother sent a card with a painting of muted flowers and wrote nothing inside. I put it in a drawer. I’m still deciding whether that was mercy.

Part V — The Fortress and the Front Door

Some endings roar. Ours didn’t. It hissed down to a clean pilot light.

A month after the dust settled, Emma handed me a tooth she’d lost at school as if I were the registrar for such things. I put it in a tiny envelope and wrote the date on it because I am the sort of parent who believes in labeling memories. She looked at it, then at me. “Can we stay here until I’m a hundred?” she asked.

“Easily,” I said. “Maybe longer.”

I replaced the last of the aluminum windows with wood and glass that told the daylight it could come in without taking over. I built bookshelves in the room that used to feel like a walkway pretending to be a study. I finished the banister spindles. I fixed the doorbell so it sang instead of coughed. I planted a tree that will outlive me.

I also changed the locks, not because I was scared, but because the ritual mattered: click, click, click, a new code for a house that had learned some words it never wanted to know.

One evening, Emma cued up the tablet again on the couch and said, “We should delete it.”

“The recording?” I asked.

“Uh-huh. We don’t need it. And I don’t want to hear it again.”

We did something ceremonial without candles. We watched the progress bar until it finished, and then we looked at each other, and she rolled her shoulders like a bird shaking out rain. “Done,” she reported, and went back to making a drawing of a house with boots.

I framed her drawing and hung it by the front door. When people ask, I tell them it’s by my favorite architect.

Sometimes, late, I stand on the porch and listen to the neighborhood exhale. If a car door slams, my heart doesn’t sprint from the couch anymore. If the wind tosses the oak, I don’t hear footsteps where there aren’t any. When I lock the door at night, the deadbolt slides home with a sound I never noticed before the trial: a small, satisfied click. I didn’t build a mansion. I built a boundary.

My parents exist now like distant weather. I monitor the forecast without letting it cancel the picnic. When they call, I answer if I can be the man I want to be on the phone. If I can’t, I don’t. It’s not punishment; it’s plumbing.

Emma still asks questions I have to earn. “Why did Grandma say it was Aunt Lily’s house?” she asked once, at the sink rinsing strawberries with the seriousness of a surgeon.

“Because sometimes grownups confuse what they want with what’s fair,” I said. “And sometimes they break the rules and call it family. We don’t do that.”

She considered this. “We do receipts,” she said.

“We do receipts,” I agreed.

The judge’s words live somewhere in the beams now, steadying them. Case dismissed. Property remains in Mr. Anderson’s ownership. Referred for potential fraud. But the sentence I hear most is Emma’s: “Can I show you something mom doesn’t know?” Not because of the theater it created in court, but because it reminded me that courage is often small, wielded by hands that hold tablets and crayons and still sleep with a stuffed bear named after a breakfast food.

They wanted a house. I built a fortress.

It’s not the kind with turrets and flags. It’s the kind that holds when a storm learns your name. It’s a front door that opens for people who knock with respect. It’s a dining table where a seven-year-old draws blueprints for a future she can live in. It’s a man who knows what it costs to stay and pays it gladly.

Justice didn’t roar for us. It whispered in a courtroom through a child’s voice and then took off its robe and sat on our porch. Now, when the porch light throws a circle on the steps and moths try their luck, I stand inside it and smile. The house is quiet. Not empty. Mine. Ours. And if a gavel ever knocks for me again, I’ll remember what silence can do when it’s backed by truth, paper, and a lock that clicks exactly the way it should.

Part VI — The Echo After the Gavel

The night after the case was dismissed, the house made new noises. Not the frightening kind; not the settling and popping that makes you stand in a hallway holding your breath. These were small approvals—pipes sighing when I ran Emma’s bath, the old fir steps murmuring under my weight like a friend clearing his throat to talk. I walked from room to room with that restless energy you get when a battle ends and your body hasn’t been told. I kept checking the windows, as if relief were weather. I locked the back door twice and then unlocked it and locked it once more because rituals matter.

Emma fell asleep drooling into the crook of her arm, tablet tucked under her pillow because heroes keep their tools close after a fight. I moved it onto her nightstand, kissed the hairline that always smells like lavender and pencil shavings, and stood there watching the jittery arc of her dream-REM behind closed lids. She was seven. She was mythic. Both could be true.

I poured a beer into a glass—because some nights deserve the ceremony—and sat on the porch, the banister a clean smooth run beneath my hand. Two neighbors walked by and pretended not to stare while they definitely stared, a Midwestern courtesy even though we live nowhere near the Midwest. The man raised two fingers in a kind of salute. The woman said, “Heard you handled it.” I shrugged. Stories travel faster than pollen.

The phone vibrated like a dog shaking itself off. Ms. Perez texted the short version: Referral filed, docketed. You’re clean. They’re… not. Sleep if you can. You did good. I typed thanks and then didn’t hit send because gratitude felt too small and too big to squeeze through satellites.

In the morning, I took Emma to school because normalcy isn’t a luxury; it’s medicine. She wore the dinosaur hoodie she calls her invisibility cloak and looked side-eyed at me when I asked if she wanted to be picked up or ride the bus. “Bus,” she declared, because independence is the currency of seven-year-olds. “But you can be at the stop and pretend to be surprised when I get off.” Compromise: the parent’s native tongue.

On the way home, I stopped at the hardware store for a new deadbolt. Not because I expected anyone to break in, but because turning a key and hearing something solid click is an addiction you earn after a scare. An older man in a blue apron asked if I needed help and then told me about a court story from 1989 involving his brother-in-law and a boat. People can’t resist when the word “lawsuit” is a fresh bruise on your face. I nodded through the saga, carried the lock to the counter, and paid in cash. Fresh starts feel better with crisp bills.

When I installed it that afternoon, I taught Emma the new code like we were whispering a spell. She had me type it once. Then she did it twice. “Again,” she said, because repetition is trust. After the fifth time, she held out her pinky for a promise. I hooked mine. “No one gives this code to anybody,” she said, sounding ninety. “Unless we decide together.” Done.

That evening, a thick envelope arrived from the court. An order formally dismissing the suit, removing the lis pendens my father had slapped onto the property like duct tape on a painting, warning the plaintiffs—my parents—that any further action without basis could result in sanctions. Legal paper smells different than other paper. Heavier. Like it expects to be respected. I slid the order into a red binder labeled DEED in block letters because there are some things your future self should be able to find without panic.

After dinner, Emma asked if we could camp in the living room. We made a tent out of a sheet and two chairs and a broom, strung Christmas lights along the goofed-up ridgepole, and lay on our backs telling each other the worst knock-knock jokes in the world until laughing hurt. She fell asleep mid-sentence, a kid’s privilege. I put my hand on the floorboards and thought, You’re mine. I’m yours. We’re not going anywhere.

Part VII — Contempt, Calendars, and Consequences

The fraud referral didn’t roar into the next day; it arrived as calendar invites and certified letters. Family court moves on schedules the way planets do—slow, inevitable, indifferent to how much you want things to hurry up. Ms. Perez asked me to gather everything: mortgage statements, closing documents, the bank wires that proved no trust had touched the down payment. I stacked them in tidy chronological order, clips at the top of each bundle, yellow sticky flags like a row of tiny tongues.

The appraiser lawyered up. My father’s lawyer submitted a letter that could be summarized as, “We meant well, we were misguided, let’s all go back to being family.” The judge assigned to the matter was not the one with the gavel thunder from our eviction day, but a man with a buzz cut and a reputation for hating games. He issued a notice: show cause hearing, sixty days. Translation: the people who played fast and loose with the truth could come explain themselves under oath.

In the interim, small skirmishes. My mother rang my phone on a Sunday afternoon while I was scraping old paint from the trim. “Emma asked about Christmas,” she began, as if we had been having a gentle conversation for weeks and had not just weaponized my child in open court. “We’ve always done Christmas morning together. The house is so big and quiet without—”

“Stop,” I said, sanding block in my hand, dust a crescent under my nails. “We’ll arrange time for you to see her. But you do not use the house as a pawn. You do not use Emma’s curiosity as leverage. And you do not come here without being asked.”

She exhaled into the receiver like a tired athlete. “You’re cruel.”

“No,” I said. “I finally learned the difference between ‘no’ and ‘maybe’.”

I kept a spiral notebook by the phone and logged every contact, date, time, content because Ms. Perez had taught me that judges love logs almost as much as they love receipts. Healthy boundaries are a dull sport. Dull is good. Dull is the opposite of trauma.

Lily posted engagement photos on a bridge at sunset, captioned “Our forever.” I scrolled past and then scrolled back, not because I wanted to look but because ignoring your past absolves no one. Ryan wore a suit he didn’t seem comfortable in. Lily’s smile tried too hard to be effortless. I clicked out of the app and went outside, where the oak was shedding leaves like a kid losing teeth, and raked. Sometimes your best answer is a predictable chore.

Two weeks later, an email slid into my inbox from Ms. Perez: opposing counsel’s supplemental. Attached, three “affidavits” from my parents and my sister, each claiming—now—that there was a handshake promise, that intentions were known, that “disappointment in our son’s life choices” necessitated creative accounting. I read them once for content and again for tone. Then I did something I hadn’t let myself do: I got mad. Not the wild kind. The constructive kind.

I pulled out the drive where I’d saved the recordings—yes, plural. The tablet captured more than the one rotten conversation that carried the day in court. There were other fragments Emma had collected because she thought “grown-ups needed receipts.” Most were useless banter. One wasn’t. It was my father in my backyard the day before the suit was filed, instructing Lily on how to answer a question about funding if it came up. His words: “You don’t need to know details, sweetheart. You just say, ‘It was always intended for me.’ People love confidence. The judge will understand family.”

I emailed the file to Ms. Perez with a single line: we use this only if they lie under oath. Her reply: I like your style.

The show cause hearing arrived on a Tuesday that pretended to be ordinary. The judge read the affidavits, listened to Ms. Perez, and then looked at my father as if examining a layer of paint to see what color it used to be. “Mr. Anderson,” he said, “were funds from a trust used to purchase your son’s home?”

“No, your honor,” my father said, and for a second I recognized the man who taught me to tie my shoes and tried not to fall asleep during my school plays. “But we intended…”

The judge held up a hand. “We’re not in the land of intentions. We’re in the land of money. Where did the money come from?”

“His settlement,” my father said, quiet now. He put his hands flat on the table as if bracing for the bus he’d finally seen coming. “And a bank. Not us.”

The judge nodded to Ms. Perez. “Motion for sanctions?”

She stood. “Yes, your honor. For filing a frivolous action and for causing a lis pendens to be recorded on a property without any basis—”

“Granted,” he said, not even waiting for the remainder. He turned to my father, then to my mother, then to Lily. “You tried to force an outcome through paperwork instead of truth. You used courts as cudgels. That ends here.”

Penalties were set—fees, the removal of the cloud on my title, a warning. The judge didn’t lecture. He didn’t need to. Consequences speak fluent English when written on official letterhead and read out loud.

On the way out of the courthouse, Lily tried to catch my eye and failed. My mother looked small and brittle. My father leaned closer and said, in a voice he imagined only I could hear, “You’ll regret this.”

“I regret a lot,” I said. “Nothing about today.”

Part VIII — Building a Life With Boring Tools

I thought the quiet after consequence would be boring. I hoped for boring. Then I found out boring is an art, and you have to practice.

I started at the edges: replacing the last cracked piece of sidewalk in front of the porch, repainting the trim around the window in Emma’s room because bright blue makes her feel like the sky belongs to her. I bought rail hooks and hung ferns because my grandmother, in a kinder generation, once told me that if a porch has ferns it forgives the house for what goes on inside.

On Saturdays, Emma and I walked to the farmers’ market. She used her own five dollars to buy something that surprised me each week: radishes with their greens on, a honey stick, a bundle of flowers with a tag that said “seconds.” On the way home she told me facts about sea otters she’d learned in school, then announced new rules for the house in a tone that made me remember she holds a robe and a gavel inside her small ribcage.

“Rule one,” she said, jumping to avoid a crack because superstition is also an art. “We tell the truth even when it’s boring. Rule two, we ask before we borrow tools. Rule three, no one can say this is not our house, not even in whisper voices.”

“Agreed,” I said, relieved to be governed.

She paused, then added a rule four. “We get a dog when I’m eight.”

“Aspirational,” I said.

At school, Emma’s teacher sent a note asking if I could come in for Career Day. I told kids that “fixing houses after lawyers try to take them” was not quite a career and then talked about being a project manager because that’s what my paycheck says I am. A boy asked how to use a drill. A girl asked how to make her mom stop crying. I showed them how to measure twice and cut once, and then I told them that sometimes the best you can do is hold the flashlight steady for the person on the ladder. We practiced holding an imaginary flashlight in pairs, one kid up, the other down, both steady. It felt like an honest use of an afternoon.

Ms. Perez checked in less as the cases wound themselves into conclusions. “You okay?” she texted sometimes, which is a deceptively difficult question. I told her yes, often. When I wasn’t, I told her no and then made a list of small things I could do that would make “no” feel like a place I could build something on—laundry, call the therapist, change the air filter, inventory the emergency kit in the hall closet because preparedness is a salve.

My ex and I managed the co-parenting calendar with a mutual respect that felt like a truce and sounded like good logistics: drop-offs without drama, check-ins without subtext, gifts to teachers signed from both of us. We aren’t saints. We just learned there are only so many house fires a child can be expected to sleep through.

A letter came from a legal aid clinic asking if I’d be willing to speak to a group of dads about boundary-setting after family lawsuits. The phrase made me laugh—there’s a club for everything—but on a Tuesday evening I drove to a room with bad coffee and folding chairs and told a dozen men the short version: record, document, don’t argue with ghosts, and when in doubt, talk to your kid about dinner, not court. One guy cried. Another asked how much a deadbolt costs. We passed around our phones and swapped numbers like we were forming a softball team with an odd rulebook.

I built a treehouse in the oak out back because there are childhood clichés you have to lean into. It wasn’t fancy. A platform. A rail. Two camp chairs. A pulley for a basket because engineering is joy. Emma and I painted the railing the kind of green you only see in cartoons. “Can we sleep out here?” she asked on the first night, as the sky pulled itself into an indigo that made the first star look like a mistake.

“We can try,” I said, carrying up two sleeping bags, three flashlights, and optimism. Around midnight she climbed down and got into her real bed because bravery is situational. I stayed a while longer and listened to the neighborhood perform its nightly chorus—the far train, the closer siren, a couple talking on their porch two houses down as if every conversation between lovers takes place under a witness moon. I went to bed feeling like a person in a movie about someone who finally got it right.

Part IX — The Knock, the Offer, and the Answer

Late summer brought a heat that made the air feel like you could step into it and leave footprints. I put a box fan in the hallway and we all pretended it helped more than it did. On a Tuesday, there was a knock I recognized without seeing. My father stood on the porch in a golf shirt, the universal uniform of men who want to appear nonthreatening. He looked smaller. Age has a way of collecting interest on pride.

“May I come in?” he asked, as if we were neighbors and not litigants.

“No,” I said, kindly because I practice. “We can talk out here.”

He scanned the porch, the rail, the ferns. “You did a good job with this,” he said, meaning more than wood.

“Thank you,” I said, meaning to accept only what was intended.

He held out an envelope. “We’re selling the lake house,” he said. “We want to split the proceeds among you and Lily.”

“Thank you,” I said again, because shock can borrow any tone. “I don’t need anything.”

“It’s not about need,” he said. “It’s about—” He stopped. Words had been expensive for him lately.

“I know what it’s about,” I said. “It’s about you wanting a version of the story where you’re generous.”

He clenched his jaw. “Do you want the money or not?”

“I want you to knock before you use my name,” I said. “I want you to never again speak to my child about where she lives. I want Christmas to be quiet. I want to be able to say no without it becoming a legal problem.”

He stared at the envelope. “I’m trying, son.”

“I see that,” I said, and I did. “Try again. Ask me what I need, not what you can give me. Those are different.”

He put the envelope back in his pocket and nodded as if someone behind him had told him what to do. “Take care,” he said, and walked down the steps. He didn’t look back. It’s progress when people keep walking.

I went inside and leaned my forehead against the cool side of the fridge like it had an oracle built in. Emma stood in the doorway, eyebrow up. “Was that Grandpa?”

“It was,” I said.

“Did he bring cake?”

“An envelope.”

She wrinkled her nose. “Cake would’ve been smarter.”

“We agree on strategy,” I said.

That night, I wrote a letter I may never send, to my parents, to the future, to whoever reads files when houses change hands. I explained the rules of this house the way you do when you leave instructions for a babysitter: how the light switches in the hallway work better if you flip the bottom one first, how the back door needs a shoulder bump when the weather swells the frame, how the little alarm bell on the window in Emma’s room is supposed to be set to chime when she gets older and starts sneaking out, how forgiveness takes the shape of boundaries you can see, not words you can’t hear. I printed it and put it in the red binder labeled DEED, behind the court order, behind the mortgage, behind the last picture Emma drew of the house with the boots.

Part X — A Clear Ending, Kept Open on Purpose

Autumn loosened the heat’s grip. Emma turned eight and declared herself ready for a puppy; we compromised with a fish we named Case Law and loved as if it were more interactive. The house decided to reward our restraint by keeping its roof on during the first storm of the season, a small mercy I thanked out loud like an oddball.

One afternoon, I found the old video on my phone—the one from court—and recognized the tightness that reappeared in my chest when the first words poured out of the tiny speaker. I hit delete. Then I emptied the trash, a digital ritual that still feels like witchcraft. Emma walked in just as my thumb hovered and said, “Do it,” so I did. “We don’t need old ghosts,” she said, and went back to teaching Case Law to do tricks you can’t teach a fish.

We hung a sign by the front door that said, This House Tells the Truth. Guests laughed. We don’t. It’s a brand, as they say in marketing. It’s a shield, as they say in therapy. It’s both.

Every now and then, when I’m putting tools away after a Saturday of small fixes, I think of that first day in court, the gavel, the feeling of my parents’ eyes on the back of my neck like heat without warmth. I remember Emma’s voice cutting through it all. Can I show you something mom doesn’t know? Courage in seven words. A better question than any cross-examination I’ve ever watched on television. The sound of a fortress being built in plain view.

Once in a while, I drive past houses for sale and look at their porches. People fall in love with thresholds. I get it. But I don’t envy them. I have what I want. A porch that forgives, a treehouse that doesn’t pretend to be a castle, a living room where tents can be made with sheets and chairs and a broom, a court order in a red binder, a kid who knows the code, a deadbolt that clicks like a closing argument, a father who learned how to say no and mean yes to the right things.

They wanted a house. I built a life.

And because you asked for a clear ending, here it is, written the way a carpenter writes in pencil before picking up the saw:

The house remains ours—legally, plainly, deeply. The people who tried to rename it were reminded that paper beats intention when it matters. The child who pressed play learned that adults can be brave, too, and that bravery looks like bedtimes kept and lunches packed and laws obeyed and boundaries respected. The family who mistook possession for love gets to try again somewhere else, with better tools and quieter voices. The porch light stays on for those who knock and tell the truth. The rest can pass by and admire the ferns.

When the judge’s voice echoes in my head—Case dismissed—I hear another sound layered under it now, steady and domestic and just as powerful: the nightly click of a lock that belongs to us, the scrape of a chair at the dinner table, the fizz of a soda poured into a glass, the hum of a fish tank where Case Law does nothing impressive and impresses us anyway. Justice didn’t just whisper in that room. It moved in. It pays rent in the currency of boring days. It leaves muddy footprints by the door sometimes. We clean them up. We go to sleep. We wake up still here.

If someday Emma asks me to tell the story again, I’ll point not to transcripts but to the banister smooth under her palm, the rebuilt porch steps that don’t creak unless you expect them to, the patch of wall where the tent once leaned, the corner where the red binder sits high out of reach. I’ll say, “This is what happened: they tried to take it; you told the truth; we stayed.” And then we’ll take the dog we will inevitably get for a walk around the block, and she’ll roll her eyes at my jokes, and we’ll wave at the neighbors who still pretend they weren’t listening when they were, and the house will wait to let us back in, a fortress with an open door.

Epilogue — The Letter I Left Behind the Deed

If you’re reading this because the house is yours now, whoever you are—my daughter grown, a kind stranger who bought it when we finally let it go—know three things. One: these floors were sanded after a storm inside a family, and they held. Two: the oak out back can hold a platform if you’re careful and patient and know someone brave. Three: justice can be loud, but more often it is this—walls that do not move when someone leans on them the wrong way, windows that open even when the paint is thick, a key code that only changes when we decide together.

They wanted a house. We made a home. And this is where it ends, on purpose: stable, ordinary, durable. A clear ending you can sit on, lean against, put your feet up in. A story that holds its shape long after the gavel’s echo fades, because a seven-year-old asked the right question and a judge listened and a father learned that sometimes the most dramatic thing you can do is install a deadbolt and keep dinner at six.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

At My Birthday Lunch, My Daughter Whispered “While I Distract Him…” But She Forgot Who Built It.

At My Birthday Lunch, My Daughter Whispered “While I Distract Him…” But She Forgot Who Built It. Part I:…

My Sister Fired Me from Our Family Foundation Then Smirked as Our Parents Called It “Fair”…

My Sister Fired Me from Our Family Foundation Then Smirked as Our Parents Called It “Fair”… Part I —…

I Found Out My Parents Gave Our Workshop Business To My Younger Brother So I Stopped Working 80…

I Found Out My Parents Gave Our Workshop Business To My Younger Brother So I Stopped Working 80… Part…

What happened to your child that made you realize nuclear was the only option?

What happened to your child that made you realize nuclear was the only option? Part I: Static Before the…

She Was Just Cleaning the Range — Until Enemy Attack Began and a SEAL Handed Her His Sniper Rifle

She Was Just Cleaning the Range — Until Enemy Attack Began and a SEAL Handed Her His Sniper Rifle …

They Mocked Her at the Gun Range — Then She Revealed She has…

They Mocked Her at the Gun Range — Then She Revealed She has… She was just a quiet nurse at…

End of content

No more pages to load