My parents sold my apartment behind my back—but they didn’t expect me to have the real deed…

Part One

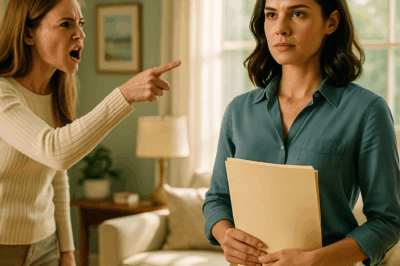

“You have thirty days to move out.”

My mother said it the way she offered people refill coffee—calm, practiced, poisonous. She stood in the middle of my kitchen drumming her manicured nails against the marble counter I had epoxied and sanded myself. Sun spilled across the floorboards my grandmother and I had refinished the summer before she died. The steel shelves still smelled faintly of cinnamon and orange peel from the morning bake. Everything inside those four walls was a map of my hands.

And yet my mother stood there as if she owned all of it.

Beside her was my younger brother, Laz, with his arm around his pregnant wife, Kala, in a tableau arranged for maximum sympathy. He gave a small shrug that might have been rehearsed in the car on the way over.

“You’re always on the road for your pop-ups anyway,” he said, as if he were doing me a favor by reassigning my life. “Kala needs a real home now, with the baby.”

The baby: their newest all-access pass. A card to be palmed at every turn. Explanations tucked behind a barely-there bump.

I let the silence lengthen. I lifted my mug and took a slow sip of coffee, and in that pause I saw it—the minute flicker in my mother’s eyes when she realized I wasn’t going to shriek. She hadn’t practiced for this version of me.

“You thought selling my apartment was a good solution?” I asked softly.

“It’s not technically yours,” she replied, plucking a thick folder from her tote. “Your father and I kept our names on the deed for tax purposes. You knew that. We signed everything yesterday.” She slid the packet across the counter with a satisfied smile. “Kala and Laz will take possession in thirty days.”

“Possession,” I echoed. The word perched in the air between us like a vulture.

I didn’t pick up her papers. I looked past them—past the powdery arrogance, past my brother’s guilty jaw, past the way Kala’s hand fluttered to her belly like a reflex—and thought of my grandmother in this very kitchen: her flour-dusted hands, the lines around her eyes when she smiled, the way her voice went quiet when she was telling the truth.

They’ll try to take it from you, she’d said, pressing an envelope into my palm three summers ago. Your mother never forgave me for giving you this place instead of her. But this is your home, Sable. I made sure it stays that way. Keep the envelope safe. Tell no one until you have to.

I set down my mug. “Before we talk about me moving out,” I said, “we should discuss something else.”

“If you’re talking about that silly office you turned the guest room into,” my mother snapped, “I’ve told you—no decent woman turns a spare room into a workspace. It’s—”

“—uncomely,” I finished for her. I’d heard variations of that sentence since I was twelve and rearranged my closet by category instead of color.

I left them in the kitchen—my tiled, sunlit, paid-for kitchen—and climbed the narrow stairs. The top drawer in the desk stuck, as it always did when the weather swelled the wood. The envelope inside slid into my hand with the cool weight of a future someone tried to steal.

Pale blue paper. My name on the front in my grandmother’s careful script. Three notarized pages. One letter. A receipt from the county registry. I touched each item once, like rosary beads, and walked back downstairs.

My mother’s face tensed when she saw what was in my hand. Not the crisp, performative packet she’d brought. Something older. More dangerous.

“What’s that?” Kala asked, her voice smaller than I’d ever heard it.

“The real deed,” I said, laying the papers on the counter. “And the transfer for the building next door.”

Laz grabbed them. With each line he read, the color leeched from his face like water from old paint. He wasn’t a reader; he was a skimmer. But you don’t skim when you realize you can’t charm paper.

“This—this can’t be valid,” my mother sputtered. “We consulted an attorney.”

“You might try consulting Grandma’s,” I said. “Mr. Langford Miles handled her affairs for thirty years. He drafted, filed, and recorded the transfer in triplicate. I have a copy. He has a copy. The county has… the copy.”

Kala’s knees touched the stool as she sat.

“You knew?” Laz asked me, panic breaking at the edges of his voice. “You knew we were planning the sale?”

“I found out weeks ago,” I said. “I could’ve stopped you then. But Grandma used to say—let people show their true colors. It saves you a thousand arguments.”

My mother stared at the documents like they might recompose themselves into the story she wanted if she exerted sufficient will.

“You should have told us,” she said finally.

“Like you told me you were selling my home?” I asked.

She looked away first.

“You don’t understand,” she hissed. “This was supposed to be my—”

“—home?” I didn’t raise my voice. “Where I lived for ten years. Where I slept on the couch when Grandma’s pain woke her at two a.m. and she asked for hot milk and we played gin rummy until the sky lightened. Where I launched a bakery from a galley kitchen because no one else would lease to me. Where you were in Napa the week she died.”

The kitchen settled into a sudden, oxygenless quiet. Laz swallowed. Kala stared at the mirror-polished sink, one hand cupped around her belly like a shield.

I gathered the envelope and slid it back into my bag. “In thirty days I’ll be where I am right now,” I said, “making cinnamon rolls for the Saturday market. You’re welcome to buy some.”

They left without the performance I expected. No slammed doors, no last takes. Just the soft give of my doormat under their shoes.

Two mornings later, someone knocked at the back door the way you knock when you’re almost sure you shouldn’t be there. The snow-globe swirl of flour in my kitchen air settled around the figure when I opened it.

Kala. Hair pulled into a loose knot. No mascara. A white bakery bag in her hands.

“I brought pastries,” she said. “Or bribes. Or an apology. I’m not sure which.”

“Better be lemon tarts,” I said, stepping aside.

She exhaled—an almost-laugh—and unwrapped two perfect tarts, an almond croissant, and four chocolate chip scones. “From Morning Finch,” she said. “You stress-ate the scones last wedding season, remember?”

I did. I didn’t reach for one.

“I didn’t know about the deed,” she said, words spilling too fast. “Laz told me your parents were giving us the apartment as a baby gift. I wanted to believe it because it made everything simple. I didn’t ask questions because I was afraid of the answers. That’s on me.”

“You never asked,” I said—not cutting, not kind. True.

She flinched. “I’m asking now.”

We stood in the smells of butter and cinnamon and cooling metal. The ovens ticked as they released heat. The refrigerator hummed. Calla’s eyes were clear for the first time since she’d married my brother.

“I meant what I said,” I told her. “Third floor, building next door. It needs work, but the bones are good. If you want it, I’ll rent it to you.”

“You’d—after—” She shook her head. “That’s generous.”

“It’s practical,” I said. “You would be my tenant, not my sister-in-law. We keep it clean: lease, rent, boundaries. You don’t shuttle information to my mother. You don’t let Laz negotiate for you. We treat each other like adults who pay what they owe and call the plumber before the ceiling turns into a waterfall.”

She laughed—a sound with sand in it and also sun.

“Laz thinks family shouldn’t pay rent,” she murmured.

“How has the no-rent family plan worked out for him so far?” I asked.

She laughed again, a shade freer, and then both our phones buzzed. I’d muted the family thread days ago; she still suffered through it.

She read aloud: Emergency family meeting Sunday. Attendance required. Your father and I have made decisions about the future of both buildings.

She looked at me, panic inflating her breath. “What are they planning?”

“Nothing that matters,” I said, a statement and a promise. “They don’t own these buildings.”

“Laz will want me to go,” she said. “United front and all that.”

“What do you want?” I asked.

She looked at her hand on her belly. She looked at the cracked light switch and the sunlight along the knob. She looked at me.

“I want my baby to grow up in a home that isn’t stolen,” she said. “I want something I said yes to.”

“I’ll have renovation plans by Friday,” I said. “Market rent. First month free while we sand floors and choose tile. You pick the paint.”

She nodded. It looked like courage learning to walk.

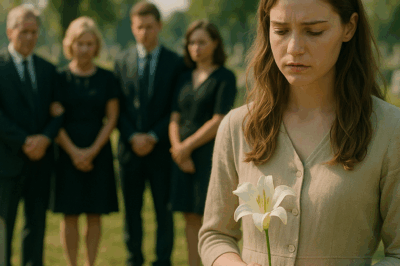

Sunday came dressed in perfect North Carolina autumn. I kept my promise to myself and to Grandma: I didn’t walk into their house to lose my home; I walked in to keep their story from eating mine. The living room was arranged like a hearing, and my mother sat like a judge in a navy dress.

My father stood behind her with a legal folder tucked under his arm and that particular aura some men have when they’ve been carrying a lie long enough to mistake it for posture. Aunts and uncles filled the side chairs in the way extended family always does when there’s the ooze of inheritance: present for the gossip, absent for the work.

Kala sat near the end of the couch. When I caught her eye, she lifted her chin—barely—but it was the first head in that house that had ever moved for me.

“We’ve been reviewing the circumstances of your grandmother’s decisions,” my father began, sliding papers onto the coffee table like he was dealing us the end. “Our lawyer has concerns about her mental state in her final months.”

He didn’t look at me when he said final months. He was smart enough not to.

“The same months,” I said, gently, “when I slept on the couch and spooned applesauce into her mouth and listened to her tell me the same story about how she met Grandpa at the train station the afternoon his beret blew off and she caught it with a cake tin. The months you spent posting photos of Tuscan sunsets.”

“The transfer was manipulated,” Laz barked. “You turned her against Mom. You took advantage.”

I looked at Kala. She stood. Every head tilted like sunflowers.

“No,” she said quietly. “Henrietta knew what she was doing. I brought her tea one afternoon and she told me she was sorry she hadn’t taught me how to make lemon curd properly yet. She said she felt better knowing Sable would keep the buildings because Sable makes things grow. She was not confused.”

“Sit down,” Laz hissed through his teeth.

“No,” she said again, louder. “I won’t sit down for theft dressed as disappointment.”

I had come prepared for a performance. I had not expected an ally.

“I brought something,” I said, pulling my phone from my pocket. I tapped the screen. The television blinked alive, and my grandmother’s face filled the room.

“Just in case,” her video-self said, eyes bright, hair tucked behind one ear the way she did it when she was about to start an argument she’d already won. “I’m recording this because I know my daughter. This building is not a bauble; it is a promise. I gave it to the only person who treated it that way.”

Mr. Langford Miles appeared beside her—a thin, watchful old man who had known us all since before we were born. He stated the date, the evaluation of competence, the witnesses. He said to the camera, “We are recording this to preempt bad faith.”

The footage ended. The room didn’t speak. Somewhere deep in the kitchen a refrigerator hummed and a clock ticked and a dog barked outside, a punctuation that felt like relief.

“How far,” I asked the room, keeping my voice egg-whip calm, “do you want to take this?”

My father snapped the folder shut. My mother swallowed. Laz’s face worked like wet clay.

“You,” he said finally to Kala, raw betrayal sparking around the edges of her name. “You knew.”

She didn’t flinch. “I asked for a lease,” she said. “Because I’d like to live in a world where I pay what I owe and don’t call theft a blessing.”

“You’re pregnant,” my mother said to her in that syrup-brick voice. “You’re emotional. Don’t—”

“Don’t dismiss me,” Kala said. “You used my baby to soften a crime. That’s the most emotional thing in this room.”

There was no yelling after that. There was no need. Gravity had shifted. People know when the room stops spinning only because one person put her foot down.

We left. At the door, Kala spoke loud enough for the room to hear, as if she were signing a document with air.

“I’d like to see those renovation plans for our new home,” she said.

Behind me, my mother’s perfect wreath swung on the door in a motion so slight I could’ve mistaken it for the beginning of apology.

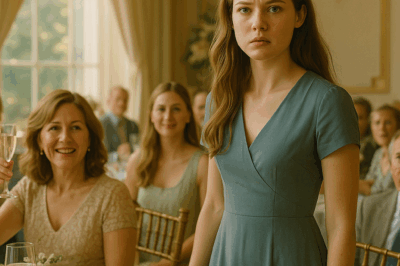

Renovation spun out of lists and dust and the small, public miracles of community. I hired Manuel and his crew to sand the floors because the machines throw up a storm and Manuel respects storms. Maria from the alterations shop drew curtains for the nursery with her grandmother’s Singer that sounds like a cricket quartet. Mr. Chen from the bookstore brought over a first-edition cookbook and told me Grandma once slipped him a pie under the counter when his wife’s chemo started.

We knocked down the arch between the living and dining rooms and found two letterpress blocks lodged in the wall from the 1920s that read YES and KEEP. We mounted them above the newly widened doorway because some houses know how to talk.

Kala rejected gray. She chose a soothing green for the nursery and a cheerful yellow tile for the kitchen backsplash that made the room feel like it remembered summer even in January. She cried once in the middle of Home Depot because picking cabinet hardware felt like admitting she might actually get the life she wanted. I pretended to study the aisle of screws until she laughed and handed me a box of brass pulls as if handing me a baton.

Laz hated the rent. I accepted it anyway, at the first of each month, with a receipt, a professional nod, and a reminder that adulthood is a rhythm, not a speech. He grumbled less after a paycheck; grumbling has a way of shrinking when you’re tired for honest reasons.

My mother stayed away until December. She arrived one afternoon with a tray covered in a dish towel the shade of lemons. She stood in my doorway like someone who has practiced using the doorbell. She said, “I made too many squares.” It wasn’t an apology; it was a sentence shaped like one. I said, “I have coffee.” We sat at my table and didn’t mention how this might be the first thing we had ever built together that wasn’t a fight.

On the day of the baby shower, the apartments collected people the way houses are supposed to: Maria and Mr. Chen argued good-naturedly over whether steamed buns or empanadas were better party food. Manuel brought a potted rosemary bush that smelled like my grandmother’s wrists. Aunt Jen told a story about Grandma cheating at cards with flour on her nose. The radiator hissed, the floor creaked, and these things sounded like a choir instead of neglect.

My mother set a tray of lemon squares on the counter and, after a moment’s hesitation, slid a handwritten recipe card next to them, as if it were a map. She didn’t ask for thanks. I didn’t offer any beyond the coffee, which was hot and strong and enough.

When the last guest left, the late afternoon poured itself across the floor like honey. Kala stood in the window of her own home and put her hand where the baby pressed back. I leaned on the doorframe of a building I wasn’t just defending anymore; I was tending.

A ping sounded on my phone. A message from my property manager: Hot water issue on 2F. Plumber scheduled. All tenants notified. Rhythm. Care. Stewardship. Words that mean more in practice than in argument.

I walked to my desk, opened the bottom drawer, and pulled out my grandmother’s letter. I didn’t need to read it; I knew it by heart. Property is more than bricks and mortar, Sable. It’s about creating spaces where people can grow. She drew a heart over the S, as if to remind me love can be policies.

I put the letter away and looked out the window. Across the alley, Maria hung the last of the nursery curtains. Downstairs, Mr. Chen turned the sign on his shop door to OPEN for late shoppers. The light caught on the brand-new brass pulls in Kala’s kitchen. The world I lived in was still stitched with betrayal, yes—but also mended with lemon curd and paint and leases and baby blankets.

My phone buzzed again. A text from Mom: Sunday dinner? I’ll bring lemon squares. You bring… nothing. Just you. There are sentences that look like surrender and are really beginnings. I typed back: Sunday at six. I’ll make coffee.

I pressed send, poured myself a cup of tea, and stood by the window. The city hummed below, a thousand private lives pushing forward. I lifted the cup and breathed the steam. I had protected a deed and won a fight. But more important, I had learned how to keep a promise—first to a woman who taught me how to stand at a counter and fold butter into flour, and then to myself.

The best revenge wasn’t telling them I told you so. It was standing in a home they couldn’t touch and growing something better in the ashes of what they tried to sell.

Part Two

The first snow of the season arrived in a hush—flurries tapping the sash, brightening the alley, frosting the iron rail as if the buildings had put on their winter shawls. I finished the last tray of cinnamon rolls, set a pot of coffee to drip, and watched the steam rise like a map of warm air.

This was the season Grandma loved. “Winter is just permission to turn inward,” she’d say, draping a quilt across her knees. “Make the inside beautiful. The outside will catch up.”

I had just poured a mug when my property manager, Tasha, texted.

FYI: man in a camel coat lingering by 112 front steps. Not ours. Scoping everything. Gave me a developer vibe.

I set my mug down. The ache that had finally begun to soften behind my ribcage flared again.

Ten minutes later, I was on the stoop in my heavy coat. The man in the camel coat had the expensive casual of someone who measured his worth in square footage and IPOs. He smiled like he had invented friendliness.

“Ms. Whitlock?” he asked, glancing at his phone as if confirming I matched the dossier. “I’m Preston Hale, Hale Urban Development. Mind if I take a minute of your time?”

I minded. But I wasn’t going to say that on my own front steps.

“Walk with me,” I said, and started down the block. He followed, adjusting a scarf that matched his coat.

“You’ve got a jewel here,” he said, hands in pockets, gaze scanning the brick and glass as if it had already been digitally rendered into assumptions. “Our firm has admired these twin buildings. We’re working on a revitalization plan. We can offer you above-market for both. Would love to talk about an exit.”

“We’re not exiting,” I said.

He kept step. “Everyone has a number.”

“Mine is in preserving what was built before me and will stand after me.”

He smiled like I’d told a joke he’d heard at an investor lunch. “Noble. But think bigger. Imagine an artisanal market, mixed-use spaces, a lifestyle gym. We’re already in talks with—”

I stopped. I turned. His cologne was too much this close—cedar and money and an insistence that everyone wanted the same things.

“You’ve been in talks with whom?”

He glanced at his phone again, faux-reluctant to reveal. “Your family, I believe. Mrs. Whitlock and Mr. Whitlock, Sr. We’ve had productive conversations. They suggested consolidation—both parcels, a clean sale. We’re prepared to move quickly.”

The cold found the seam at the back of my neck and slipped in.

“They don’t have standing,” I said. “They don’t own either building.”

“Families can be messy,” he replied, lowering his voice. “Which is why we like to make it easy.”

I smiled in a way that wasn’t one. “Nothing about this is easy for you.”

He blinked. His smile faltered. It’s a particular joy to watch the moment a man realizes you aren’t the version of woman he’s prepared for.

“Have a good morning, Mr. Hale,” I said, and walked back to my door.

By noon, the emails began. First from his assistant, then a generic letter of intent, then a sanitized press deck about “urban uplift” that used the word community fourteen times without naming a single person who actually lived on this street. I sent them to Tasha with one line: “File under seasonal spam.”

Two days later, my father called.

“We need to talk,” he said, skipping hello. “A developer wants to do something for the block. Don’t be stubborn. This isn’t personal. It’s business.”

“It’s stewardship,” I said. “Also, you’re not consulted on business here.”

He cleared his throat. “Don’t be naïve. Money is the adult way to settle grudges.”

“You mistake New Year’s resolutions for apologies,” I said. “Grudges imply I’m still standing in your house waiting for you to open the door.”

There was silence. He gripped it like a railing. “We can make a lot. You can make a lot. This would—”

“—undo everything Grandma put in my hands,” I said.

Another silence. Lighter this time, less of a threat, more of a hit golf ball you can’t find.

“Your mother wants to—” he started.

“—bring lemon squares,” I said. “She can. We’re not selling.”

He hung up without goodbye. A familiar sound. It didn’t pierce like it used to.

That night, I called Mr. Langford Miles. He was ninety if he was a day, but still answered his own phone with a crispness I envied.

“Mr. Miles,” I said, “I need to formalize something Grandma and I only ever talked about.”

“Your grandmother’s ghost has been tapping me on the shoulder for weeks,” he said. “Tell me.”

“I want to protect the buildings from anyone—including me—making a short-sighted decision,” I said. “A trust. A stewardship covenant. A way to keep what we’ve built from being packaged as an exit plan the moment the right check clears.”

He hummed. Paper crackled on his end. “Property is as much paper as brick. We’ll make the paper heavier than the buyout.”

We drafted for a month—careful clauses, right of first refusal for tenants, board oversight, a purpose statement that spelled out exactly why these two buildings existed at all. We named the trust The Henrietta Fund.

When the documents were ready, I hosted a potluck at my place. Tenants climbed the stairs with dishes—stews and salads and empanadas and Mr. Chen’s steamed buns, which he pressed into my hands as if they were part of the ritual. We pushed the tables together and turned off the overhead light and talked by lamplight about duty.

I stood at the end with the folder and told them what this meant.

“It means if a man in a camel coat knocks on any of your doors,” I said, “you send him to me. It means rent will be market, maintained, and not a wedge to squeeze anyone out. It means we fix the roof before it ruins the piano. It means when one of us is sick, we bring soup before we bring questions.”

“And when your mother is angry?” Manuel asked, only half joking.

“Then we make her lemon squares,” I said, to laughter, and placed the papers on the table like bread.

We signed. One by one. Names stacked like a backbone.

Winter turned the alley into a tunnel of breath. The bakery did well—holiday orders pulled us through the short days. I hired two part-timers and bought a used mixer that grumbled like an uncle and worked like a saint.

Kala’s flower orders grew too. Shopkeepers called her by name. Mr. Chen set up a little display in his window—secondhand books tied with jute and a wild little bouquet on top—and put a hand-lettered sign next to it: “Stories & Stems—Ask for Kala.”

Laz commuted to Atlanta three days a week and came home tired in a way that made him kind. He still bristled when he wrote the rent check, but his bristle softened under lack of audience. He began to fix things before I noticed they were broken. On a Saturday in February, I found him in the basement with Manuel, rewiring a faulty light. He looked up like a boy caught pocketing cookies and then held the ladder while Manuel worked, and it was the smallest apology that ever felt like something.

In March, the trust filed. It was done. Paper upon paper. My grandmother would have loved the ceremony of it—the way we wrote our names on lines that turned air into law. We toasted with coffee and tart apple cider and considered building a custom sign for the foyer: The Henrietta Fund—Established to Keep the Lights On and the Wolves Out.

“Hale called again,” Tasha told me the following week. “Same number. Left a voicemail pretending his last three emails had been lost in the ether. Do you want to respond?”

“No,” I said. “But I want him to learn.”

“What lesson?”

“That ‘no’ is a complete sentence,” I said.

She grinned. “I’ll print the trust’s statement of purpose and courier it with a basil plant.”

“Why a basil plant?”

“So his office smells like something living,” she said, and I laughed until the oven timer pinged.

The only real complication arrived on a rainy Tuesday when the door buzzer wheezed and I heard my mother’s voice. I had taken to bracing myself, as if a step could be rehearsed. It never helps. But this time she was carrying Tupperware and a manila envelope and wearing her hair like she had an appointment.

“Come in,” I said.

She put the containers on the counter without the old flourish. “Chicken stew,” she said quietly. “Your grandmother’s. I wrote down what I remember.”

“And the envelope?”

She hesitated. “Your father spoke with that developer,” she said, watching the floor. “Again. He didn’t tell me at first. I only found out because I saw a check stub—not from them, from him. He put down a deposit on a boat.”

My stomach dropped into an old, familiar well. “On a what.”

“He always wanted one,” she said, as if the sentence could excuse a theft. Then she shook her head, quick, like she was catching herself reaching for an old coat that didn’t fit anymore. “He told me we needed to move forward. He told me you were being selfish. I told him I was tired of being used as a bridge while he stamped his feet on the other side.”

I leaned against the counter. “What do you want, Mom?”

She opened the envelope. Inside was a list—her hand but neat, the kind of neat that takes time. Names of charities. A typed letter to Mr. Hale stating clearly that neither she nor my father owned nor could promise or negotiate anything about either property. A copy of the trust’s purpose. And, at the bottom, a small recipe card in her tight script: lemon squares, revised—less sugar.

I laughed, then felt my eyes go damp in spite of myself.

“I can’t undo what I did,” she said. “But I can stop doing it. That’s something, isn’t it?”

“It’s a start,” I said, and meant it. “Do you want to help with something real?”

“What?”

“A block party,” I said. “Midsummer. Bring your lemon squares.”

She smiled and it softened lines I had grown used to reading as permanent.

Spring loosened and let go. The alley filled with children’s chalk drawings and the smell of basil in windowsills. I expanded into the corner space on the first floor—my grandmother’s “one day” thrown forward, caught, set down. I kept the home bakery in my kitchen; the corner space became a community kitchen. Thursday nights, we hosted a pay-what-you-can dinner. Mr. Chen read a poem once about oranges that made a boy at the end of the table cry into his spaghetti. Manuel taught a kid how to use a drill. Maria fixed a hem for a woman on her way to a job interview. It never made money. It made everything else.

In May, the baby came fast and dangerous and then safe—pink and wailing and furious at the cold. Kala texted me at midnight: Water broke. His phone’s dead. Don’t panic. Hospital. I packed a bag like a thief—blanket, lavender oil, lemon candies—and sat with her when Laz sprinted to parking. The doctor looked twelve and spoke like someone who’d already shepherded forty lives into fifty rooms. In the corridor, I whispered to the universe that if it let this baby arrive breathing, I’d never roll my eyes at a motivational quote again.

She arrived breathing. Kala named her Henrietta and I cried into a towel and didn’t care who saw.

When they brought her home two days later, the building clapped. Not politely. Not like a golf course. Like joy has hands.

Laz taped the baby’s emergency contact on the fridge and underlined my name as if to tattoo the fact that I showed up. My mother came with lemon squares and a soft, stunned look. My father stood in the hallway like a man who couldn’t find an angle. He didn’t hold the baby. He stood near the coat hooks and spoke to her, awkwardly, like he’d never spoken to something purely good.

“Welcome,” he said, voice rough. “You’re the only thing anyone has done right in this family for a minute.”

It wasn’t my apology. It wasn’t his either. But it was a sentence I could live with.

The block party was stupid and wonderful. Bunting zigzagged between second-story windows. Manuel hauled grills into the alley and flipped burgers while Mr. Chen made tea and told a story about being twenty and thinking America smelled like laundry detergent. A band formed spontaneously: a ten-year-old with a ukulele, a teenager with a drum pad, an old man with spoons. My mother danced with Maria. Kala cried quietly when she saw her daughter’s name chalked in huge letters under the stoop.

Hale showed up around two, because of course he did. He stood at the end of the alley, sunglasses bright, assessing like the ant at a picnic who’s sure he invented sugar.

Tasha intercepted him.

“Festival’s for tenants and their guests,” she said. “This alley is private.”

He smiled. “I’m a guest.”

“You’re not,” she said. “But I’ll let you stand there and smell the food for five minutes if you promise to watch something.”

“Watch what?”

She pointed to the banner strung between the buildings: THE HENRIETTA FUND—WE DON’T SELL WHAT WE’RE STILL USING.

He tilted his head, read it again, and left.

I’d been carrying a folding chair. I set it down and sat. Sometimes victory is the act of not moving.

That night, after the alley had emptied and the grills had cooled and Manuel had danced with a broom in the way men who have lived long enough let their hands teach their feet, I stood in the middle of the brick and listened. The buildings hummed. Not metaphoric humming. Real humming—pipes and vents and radiators and the low, content noise of systems working.

I thought of my grandmother, of the envelope worn smooth by three years of hiding, of the way she’d looked at me when she said hold the line. I thought of my mother, handing me a recipe card like truce, of Kala, standing in an empty apartment and seeing walls. I thought of myself—Sable, who had stopped being a walking bandage and started being a steward and a baker and a woman who could say no without explaining.

My phone buzzed. A text from my father: Your party was nice. Your grandmother would’ve approved. Don’t tell your mother I said that. Goodnight.

I laughed out loud in the empty alley.

Inside, my kitchen smelled like sugar and sleep. I washed the last bowl. I put the trust folder back in the drawer where Grandma’s letter lived and locked it. Not because paper can save you from people who don’t care about paper—but because it reminds you who you are when someone tries to write over you.

I made tea and carried it to the window. Light pooled in the units across the way. In one, Maria’s Singer chattered like crickets. In another, Mr. Chen read at his counter, his face bent over a page he’d surely read before. Upstairs, Kala walked the baby in a slow figure-eight that turned into a lullaby. Down the hall, Laz washed dinner plates, sleeves rolled, face softened by the very boringness he used to mock. My mother sat at my table, fiddling with her recipe cards and muttering notes to herself. She’d found a way to make the lemon squares less sweet and somehow they tasted more like themselves.

The city breathed. The buildings breathed. I breathed.

There are stories where revenge is a headline. This isn’t one. The headline never came. The developer moved on to a neighborhood that didn’t know how to say ours. My parents didn’t become saints. They learned to sit with their hands in their laps while other people spoke. Laz did not suddenly turn into a man you’d trust with a mortgage, but he turned into one who mops and shows up, which sometimes is enough. Kala’s flowers refused to apologize for being bright. My bakery paid for a new roof without a fundraising campaign or self-congratulation.

And the deed—real and heavy and filed and folded and fingerprinted—lived where it belonged: not just in a metal drawer, but in the way people carried groceries upstairs for each other, in the rent paid on time, in the lemon squares cooling on my counter while my mother scribbled the recipe again so she wouldn’t forget what we’d changed.

I set my mug down and traced the window frame with my finger, the wood smooth under paint. The best revenge wasn’t the day we beat a developer. It wasn’t even the day my mother stopped performing grief and started practicing love. The best revenge was this—staying. Making something that doesn’t fit into a glossy brochure. Growing something stubborn and good where someone else saw an exit.

Grandma used to end our baking days with the same words, said half to the dough and half to me: “There now. Let it rest. You did your part. The rest is rising.”

I turned off the light and let the buildings hum.

END!

News

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… CH2

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… Part One I…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited me Over Just to Tell me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited Me Over Just to Tell Me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her …

At My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. CH2

My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. Part One…

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And then.. CH2

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And…

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a… CH2

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a … Part…

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration. CH2

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load