My Parents Skipped My Wedding, Calling It “A Trivial Event For Someone At The Bottom.” So I…

Part One

My name is Isabella Reed. I grew up on a quiet block in Toledo, Ohio, in a house where the furniture never gathered dust and the front lawn looked ready for a calendar photo shoot. My parents, Joseph and Ruth, ran our home according to a simple creed: polish the surface and people will believe in the shine. Holiday cards were immaculate; centerpieces matched the season; smiles crystallized for photos even if a storm was rattling the windows ten minutes before.

From the time I could read, I understood which stories made it onto the card and which got filed away. My older sister, Cheryl, was a perennial headline: honor roll, debate team captain, future of the family. Even when she giggled through a misstep, adults called it charisma and clapped. I was quieter; I drew cityscapes on scrap paper and cut letters from magazines to make my own logos. When I slid a drawing across the dining table, my dad barely looked up. “That’s nice, Isabella,” he said, then launched into a recap of Cheryl’s debate victory. It was the first of a thousand little times I watched something I made fade under the hum of her spotlight.

When I was ten, I won a school art contest. I ran home with the certificate—cheap paper, cheap ink, huge pride—and stood at the threshold of the living room, waiting for them to look up. My mom smiled without teeth. “Good job,” she said, then turned back to hanging Cheryl’s medals along the staircase where guests would see them. For Cheryl’s graduation, they rented a tent and strung lights in the backyard; for my straight A’s, there was a high-five that landed off-center.

The pattern calcified. Cheryl got a new laptop “for her future”—necessary equipment for victories still in the planning phase. I got a hand-me-down sketchpad from the craft store bargain bin. They drove hours to watch her competitions, ironed her suits, set her alarms. When my first art show went up at fourteen in the high school gym, they “had work.” I stood under fluorescent lights while other parents took photos and pretended not to notice the empty space where mine would have been. That night I overheard my mother telling a neighbor, with the certainty of someone placing a bet, “Cheryl is going places.” I sat on the staircase with a drawing in my lap and understood I would always be the understudy in a play that had already cast itself.

By senior year, I stopped asking for center stage in their story. I poured the ache into a portfolio and, with my art teacher’s fierce encouragement, earned a scholarship for graphic design. My parents told me to be practical. They mortgaged Cheryl’s future like an investment and called my scholarship “lucky.” I saved the email from the gallery in Toledo that invited me to exhibit when I was eighteen; I also saved the evite they sent out for the party they hosted the same night for Cheryl’s law school acceptance. I stood in the gallery ringed by strangers who liked my lines and colors; I went home with sore cheeks from smiling and a new resolve: to stop trying to convince my parents I belonged in their narrative and write my own.

College felt like air after a long swim. In an intro to design class, I met Michael Foster, the TA with a soft laugh and a surgeon’s eye for composition. He looked at my rough logo for a student club and asked real questions: “What do you want someone to feel when they see this?” I talked too fast. He nodded, told me which corners needed tightening, and walked me to the campus café where he ordered coffee for both of us and asked more. Around the same time, I met Nicole Hayes—photography major, fierce and funny—who critiqued my work with a scalpel and cheered with a megaphone. With them, my drawings stopped feeling like a private language and became a way of talking I wanted to use forever.

I worked hard. I was the person who fixed an icon at 2 a.m. because the curve didn’t feel honest, the intern who asked the local studio if I could sit in on client meetings and took notes like they were audition tapes for a future I could see. I sent my parents updates out of habit; the responses came back thin. “That’s nice,” my dad texted once, followed by, “Cheryl is interning at a prestigious firm.” Nicole rolled her eyes so hard I thought they might get stuck. “They don’t deserve your wins,” she said. Michael poured me a second coffee and asked about my type choices like the answer mattered.

By my mid-twenties, the things I had imagined started to stand on their own. A regional agency hired me; a campaign I led got written up in a local industry blog; a chain of coffee shops let me reimagine their brand, scent by scent, cup by cup. When the agency tapped me as lead designer on a national rebrand—a six-figure contract, the kind people put in their LinkedIn headlines—I told my parents out of the reflex we all try to put down. “That sounds like a lot of work,” my mother said, then asked if I’d congratulated Cheryl on her latest win. I cut that reflex that day and this is the one milestone I marked because of them.

The rest of my life, the part that mattered, grew anyway. Michael and I walked along the river one brisk evening and he asked me to spend the rest of my life next to him. I said yes into his shoulder. We planned a small wedding by the water at a restaurant with brick walls and good bread, guest list short enough to seat everyone who truly knew us. I designed the invitations—letterpress, a delicate line drawing of the view from the patio—and wrote my parents’ names at the top of the list as if they belonged there.

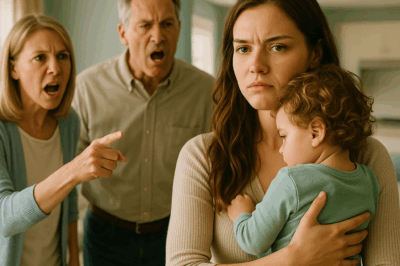

I mailed the invitations and called to confirm because hope is a moth that returns to burned places. My father texted, “We’ll try to make it.” Cheryl didn’t respond. Four days before the wedding, my mother called. “Isabella,” she said, voice clipped smooth, “we’re not coming. This is a trivial event for someone at the bottom. Cheryl’s engagement is a big moment for us; we’re flying to Hawaii to celebrate.” She said us as if the word couldn’t bear weight unless it excluded me.

On my wedding day, I walked down the aisle in a dress I designed, the seams holding because I learned where a garment should carry softness and where it should not give an inch. I glanced at the chairs that had their names on them; they stared back blank. Michael’s vows steadied the floor under my feet. Nicole took pictures of me laughing with my eyes open. Michael’s parents, George and Diane, pulled me into a hug that did not ask questions about blood.

After the final dance, I checked my phone the way a person touches a bruise, just to see. A notification from my mother. A video: Joseph and Ruth and Cheryl and Jeffrey on a beach, drinks held high, laughing against a sun that looked like a movie. “Celebrating our star’s engagement in paradise,” the caption read. The word star landed where a father-daughter dance should have been. I watched it twice. When Michael asked if I was okay, I said yes and let him hold me while that answer rearranged itself into something true.

A week later, my father called. “We need to talk about the loan,” he said, business voice on. “Twenty thousand from your college days. It’s fair you contribute now—Cheryl’s wedding is a big deal for the family.” He said loan like an invention, family like a bill.

I hung up, pulled out a folder, and lined up six years of bank statements on the kitchen table. I had paid my loans on time, from my account, month after month after month. I called my bank anyway. “Paid in full,” the representative said. “No outstanding debt tied to any Joseph or Ruth.” The line went quiet when I called my father back and said the words. He tried to pivot, calling Cheryl’s wedding a “family priority.” I threw my mother’s words back. “Don’t contact me about trivial matters,” I said, and hung up while my own hands shook.

That night, Michael made tea and set it in front of me like a promise. Nicole sent a string of capital letters and then came over anyway with takeout and casually suggested we smash something small (we chose eggshells over my sink; it was both absurd and perfect). George and Diane showed up two days later with a casserole and a story about how choosing peace sometimes looks like closing a door. It wasn’t just that the people I loved didn’t leave; it was that they knew which chair to bring and how to set it down.

I made a decision that had been sharpening itself for years. I found Dr. Pamela Scott, a therapist with a voice like a well-made hallway, and told her the parts of the story that still knotted my breath. “You’ve been walking uphill carrying their expectations,” she said. “Boundaries aren’t punishment; they’re the ground under your feet.” I believed her.

At our kitchen table, with Michael’s hand on mine and Nicole ready to proofread, I drafted an email addressed to Joseph, Ruth, and Cheryl. It was short. It did not perform pain. I wrote: Your actions have shown me where I stand in your lives—from years of favoritism, to dismissing my wedding as trivial, to demanding money for Cheryl’s event under the guise of a loan that never existed. I will no longer carry the weight of your expectations. Do not contact me again. Any future attempts will be ignored. I hit send. Then I blocked numbers and accounts and let the silence be a balcony, not a cliff.

Part Two

In the first week after the email, my hands kept reaching for my phone as if I could catch a message before it landed. None came. Dr. Scott told me that silence from people who have always spoken over you is not proof you were wrong to speak. “This is grief,” she said. “But it’s also space. Fill it on purpose.”

I did. My work became the place I turned with both hands. I led a campaign that had me sketching in the morning, researching in the afternoon, and arguing for good typography in meetings where people had never been asked to care. My designs began to look less like persuasion and more like honesty. Michael noticed before I did; he kissed my forehead when I fell asleep on the couch with a pen still behind my ear and said, “You’re glowing,” in the same tone he uses when light cuts through a storm.

My cousin Mary asked me out for coffee and said, without preamble, “What they did at your wedding is unforgivable.” She turned her mug and told me she had stopped inviting Joseph and Ruth to things. “People are starting to see it,” she said. I didn’t need that justice; I also didn’t refuse it. When Mary texted later to say that at a family gathering Jeffrey’s mother had looked Cheryl in the eye and said, “You cannot expect to be celebrated while your sister is ignored,” I did not take a victory lap in my living room. I did breathe easier.

Consequences accumulated around them without my participation. Neighbors who used to wave with both hands now lifted one. The aunt who had always played neutral started replying we have plans to Joseph’s invites. Cheryl’s engagement, once a parade, hit a snag. Jeffrey’s family valued fairness and said so out loud. Cheryl learned that silence is an answer, too.

I learned softer things. The way the light moves across our living room at four p.m. in the winter and makes a square on the floor where everything seems possible. How Nicole can tell when I need a gallery and when I need fries. The precise moment in the morning when our apartment smells like coffee and new paper and hope. How George tells stories you can live inside, and how Diane holds a baby like she’s playing a song only they can hear.

One evening Michael and I took our usual walk along the river. The water was dark and fast, and my fingers were cold inside his. He stopped under a streetlight and put his other hand on my cheek. “We have room for someone else,” he said, and asked me a question we had both been moving toward. I said yes twice.

Emma arrived on a Tuesday morning in a block of sunlight. The nurse placed a bundle of new life on my chest and the world rearranged itself around her weight. She looked at me with that unfocused newborn gaze that feels like a promise you intend to keep. Michael cried. I laughed. Nicole burst into the hospital room with flowers that clashed with everything and took pictures that made me look like the best version of myself. Diane and George cooed and brought soup, and George told Emma a story about a little girl who went looking for herself and found everything she needed, which made absolutely no sense; we all cried anyway.

I stood in the nursery in the weeks that followed, paint on my hands and awe in my throat. I had designed patterns for clients for years—wheat fields and rooftops and abstract waves that matched a brand manual. The pattern on Emma’s wall arrived without a brief: a trail of stars that doubled back on itself, then chose its own way forward. I wrote on a sticky note, Family is who shows up, and tucked it inside a drawer I kept for things I wanted her to find when she was older.

George and Diane became grandparents not by title but by deed. George taught Emma to blow raspberries; Diane knitted a sweater with buttons that looked like moons. Mary became the kind of aunt you text first. Nicole photographed Emma asleep on my chest, my hair messy and my face unguarded, and when she showed me the picture, I had to sit down because I recognized the woman in it. She looked like someone who had chosen herself and then chosen others from that solid ground.

Dr. Scott asked me what it felt like to hold my daughter. “Like everything I didn’t get and everything I learned about how to live anyway,” I said. She nodded and reminded me something I hadn’t realized I needed to hear: that parenting is an act of forgiveness as much as it is one of intention. “Not forgiving what happened to you,” she clarified. “Forgiving yourself for the years you spent trying to earn what you were owed.”

Work did not vanish under diapers and sleep schedules. I took a leave when Emma arrived and came back to the studio in a way that let me be both designer and mother without lying to either. Michael and I made a schedule that looked implausible on paper and doable in real life because we anchored it in respect. I stopped apologizing for the hour I took to nurse a baby and the hour I asked to perfect a kerning pair. The men in my meetings learned that the woman who talks about baselines can also turn a lullaby into air. The women did not need to learn anything they didn’t already know.

One afternoon, I opened a drawer and found the email I had printed before sending—the boundary I wrote so carefully I could have carved it in wood. I re-read it not to pick at a scar but to admire a seam. It had held. In the months since, Joseph and Ruth had not called. Cheryl had not texted. The part of me that used to flinch at sidewalks I knew they walked on now moved without scanning the horizon. I felt safer inside my own life than I ever had in their house.

A year after the wedding, Nicole and Michael put together a photo book. On the last page, she wrote in her messy, fierce hand: You didn’t just survive. You made meaning. When I flipped to the front, I saw me in a dress I designed, eyes clear; Michael’s face open and sure; Nicole mid-laugh; George toasting; Diane’s hand on mine; Mary leaning in; a tiny square, printed later and pasted in, of Emma squinting at the sun in a hat too big. There were no empty chairs in those photos because we didn’t set them out.

News about my parents reached me like weather reports I didn’t put much stock in. A neighbor told Mary that Joseph was quieter. Someone said Ruth had offered a brittle apology to a cousin at a reunion that felt like a performance even before it hit the floor. Cheryl and Jeffrey were taking a break “to reassess priorities.” None of it was mine to fix or to celebrate. Dr. Scott would call it evidence that boundaries tell stories even after you speak them out loud.

When Emma turned one, we held a small party. A sheet cake that leaned a little to the left; a streamer Nicole insisted on buying because she likes exuberance; a playlist Michael made that had too much of one band we both like. Emma ate frosting like it was her first language. I looked around at the people in our living room—Michael, Nicole, Mary, George and Diane—and understood why my chest ached without hurting. That ache was fullness. It used to be longing.

As the last guest left, Michael wrapped his arms around me in the doorway. The evening light made a square on the floor where the rug always shows off. “Do you ever think about calling them?” he asked gently, not because he wanted me to, but because he wanted to know where my mind wandered.

“Sometimes,” I said, which was true. “Then I look at this.” I gestured at the cake crumbs, the stack of plates, the lopsided streamer, the nursery down the hall, the drawing taped to the fridge that Emma had made with Nicole’s help—two circles and a line, most likely a portrait of someone in the room. “And I don’t.” He nodded. We stood there for a minute. The house breathed. Emma laughed in her sleep.

That night, I sat at my desk while the baby monitor hummed, and I wrote a note to my daughter. You will be loved for who you are. When you tell us what you love, we will listen. When you draw, we will look. When you speak, we will hear you. And if the world calls your big days small, we will still show up in shoes that are easy to stand in.

I folded the note and put it under the sticky note in the drawer that says Family is who shows up. Then I opened my laptop and finished a logo for a client who trusted me because I had learned how to trust myself.

The morning after, Nicole sent a text that read: Remember when you used to ask me if it was okay to be happy? I laughed and didn’t answer because I was busy being the thing I had asked permission for.

This is the ending that a younger version of me didn’t know how to imagine: not a showdown, not a victory speech, not a shot of me closing a door while a camera pans out. My parents skipped my wedding, called it trivial, then tried to make me fund my sister’s big day with a debt I didn’t owe. So I chose a life where none of that defines whether I get to be seen. I wrote a boundary and kept it. I built a family out of people who know the difference between obligation and love. I stood at an altar and married a man who keeps promises, held a child who will never have to wonder what it takes to earn our presence, and designed a life that looks good because it is good.

If there’s anything I want you to take from my story, it’s not the list of hurts or the appeal for a particular kind of justice. It’s the fact that you can stop asking to be invited to a table that was never set for you and build one with your own hands. The chairs will fill. The light will find it. And when you look up, you won’t be at the bottom of anything. You’ll be home.

END!

News

“You And Your Kid Are Just Freeloaders!” My Parents Screamed In My Face — While Living In My House. CH2

“You And Your Kid Are Just Freeloaders!” My Parents Screamed In My Face — While Living In My House. …

My Parents Left Me Alone in a Coma at the Hospital — But When They Saw Me in Court, They Collapsed.. CH2

My Parents Left Me Alone in a Coma at the Hospital — But When They Saw Me in Court, They…

My Sister Announced She’s Pregnant for the 5th Time, but I’m Tired of Raising Her Kids, So I… CH2

My Sister Announced She’s Pregnant for the 5th Time, but I’m Tired of Raising Her Kids, So I… Part…

My Parents Threw Wine At Me And Kicked Me Out After I Refused To Pay My Brother’s $250K Debt So I… CH2

My Parents Threw Wine At Me And Kicked Me Out After I Refused To Pay My Brother’s $250K Debt So…

At The Family Party, My Parents Seated Me Next To The Gift Table Like A Servant. CH2

At The Family Party, My Parents Seated Me Next To The Gift Table Like A Servant – So I… …

My Parents Forgot My Birthday. But Remembered My Card No. For Their All-Inclusive Trip. And Then… CH2

My Parents Forgot My Birthday. But Remembered My Card No. For Their All-Inclusive Trip. And Then… Part One My…

End of content

No more pages to load