My Parents Skipped My Wedding, Calling It “A Trivial Event For Someone At The Bottom,” But I Proved Them Wrong

Part One

The text arrived twelve minutes after the florist pinned the last sprig of rosemary into my bouquet.

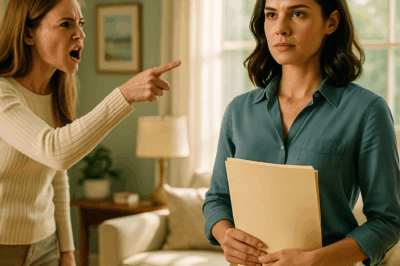

We will not be attending. We cannot support a trivial event for someone who has chosen a life at the bottom. This is not the family standard.

There it was—three sentences that managed to be both brittle and barbed, the way only my parents’ words could be. I read them once. Twice. A third time, as if repetition could turn cruelty into misunderstanding.

“Clara?” Sarah’s reflection hovered behind mine in the bridal suite mirror, soft pink lipstick, soft brown eyes, everything soft except the way she was looking at my phone. “What’s wrong? You look like you swallowed the ocean.”

I handed her the screen. “They’re not coming.”

Sarah didn’t say, I’m sure they’ll change their minds or They wouldn’t. She knew better. She knew the way my parents lived their lives like a performance of control, the way the prologue to any big day I had—the scholarship announcement, the bakery’s ribbon cutting—was not joy but judgment.

An email buzzed in right after. Subject line: Regarding the Bennett family’s attendance. CC: every aunt, uncle, cousin, and person whose approval my mother measured in martinis.

…we cannot participate in events that do not reflect the values of excellence and ambition we have instilled in our children. We hope Clara and her husband understand that our resources and support are reserved for endeavors that elevate the family name.

The ellipsis before husband was a tiny, elegant knife.

I pictured the scene in their kitchen: the gilt edges of their espresso cups, my mother’s manicured finger tapping her phone, my father waiting to say something clever enough to sound like a standard, and my sister Jessica—bride-to-be in six months—nudging the knife in a little farther with a smile.

My throat burned. The dress that had felt like a soft embrace ten minutes earlier now itched down my spine. Leo would be downstairs soon, tying and untying his tie until his mother swatted his hands. The sun was doing that late-afternoon thing where it poured molten gold through every window of the old carriage house we’d rented and made the dust dance like confetti. The band was tuning “Here Comes the Sun” because Leo had insisted on a Beatles nod like a kid.

“Breathe,” Sarah ordered. She slid my phone into her clutch and pressed my shoulders down into the chair. “We will get through this ceremony. Then we will eat cake. Then we will make a list. You’re good at lists.”

“I’m a baker,” I said, the word suddenly feeling like apology more than pride. “Apparently that’s life at the bottom.”

Sarah’s eyes flashed. “Apparently your parents don’t understand that flour and fire turn into a living, that mornings that start at three a.m. are ambition, that a line down the block is a standard.”

A knock sounded. Leo leaned in, the wrong side of superstition, because he couldn’t wait. He took me in the way he always does—first with his eyes, then with the muscles of his face relaxing, then with that small exhale that tries not to make a moment bigger than it is and fails.

“You’re okay?” he asked, and the way he held the question made room for more than one answer.

“My parents aren’t coming,” I said.

He closed his eyes. Opened them. “Then I’ll walk you down the aisle, and when you need to lean, lean on me.”

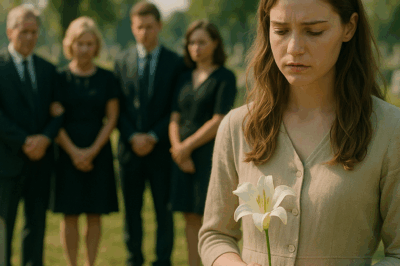

We married under a canopy of olive branches and fairy lights strung by my landlord’s teenage sons in exchange for éclairs. Sarah fixed my veil twice because my hands were no longer capable of tying knots. Leo’s vows were a love letter to ordinary days. Mine were a promise to never talk about work at 3 a.m. unless the oven had truly caught fire.

When we kissed, the room sighed. When we danced, my father wasn’t there. His absence was a shape at the edge of every photo. His chair at the front was dressed but unoccupied. My mother’s perfume—white lilies and judgement—wasn’t there to make the air feel tight.

I didn’t cry until after. Not during the cake cutting, where Leo’s mother pressed a napkin into my palm and said, “You have such a steady hand. Doesn’t she, everyone?” Not during the bouquet toss that devolved into chaos because my friends were too practical to lunge for flowers. Not even when Sarah delivered a toast that used the word tenacity without sounding like she’d swallowed a motivational poster.

I cried at midnight in the hotel room when I saw my mother’s email had been forwarded—again—to my cousin Liam in Houston and to Aunt June in Scottsdale. I cried because it was never enough to wound me once; their hurt had to be a performance other people applauded.

Leo brought me water and a legal pad. “List,” he said. “Not of their sins. Of your plans.”

He knows me.

Two years earlier, when the ink was still wet on the lease to my tiny bakery—three hundred square feet, a secondhand oven named Clementine, a front window that fogged up in winter like a child pressed against a toy store—I had an unlikely regular.

He wore tweed in the summer and read books that smelled like a library roof in a rainstorm. He never ordered anything sweet-sounding; he always ordered “whatever today feels like.” He left handwritten notes on napkins.

You overwhip your cream when you’re angry. Learn your patience like a tool.

Your kouign-amann tastes like you forgive people too quickly. More salt.

He signed nothing. He left no name. He tipped like a man who believes in futures.

The day he didn’t come in, I noticed. The week he didn’t, I worried. A month later, a letter on heavy paper arrived from a lawyer whose firm name sounded like old stained glass. Miss Davies wrote that her late client, a Mr. Alistair (the mystery solved), had left a trust—small by corporate standards, enormous to a woman who could recite the price of butter in three languages—earmarked for “culinary ventures that make the world more beautiful.”

It was a trust with a catch: it would remain in quiet escrow until I presented a plan that matched the size of the gift with the size of my imagination. It would not fund rent; it would not cover flour in perpetuity. It would be unlocked by boldness.

I built my case like a cake. Layers: a new patisserie in a building with bones and a story, classes that made butter less mysterious to people who’d been told the kitchen wasn’t theirs, a rotating menu that treated pastries like seasons—brief and intense and remembered. I slipped community in between like ganache—paid internships for kids from the neighborhood, a once-a-week pay-what-you-can morning where the line would be proof that dignity tastes like coffee and sugar and doesn’t ask you to say please.

Miss Davies said yes with the kind of smile that looks like a secret handshake between women across time. The trust would remain anonymous; the building would not. She’d acquired, through a series of calls that sounded like chess moves more than real estate transactions, a historic storefront my father had once described as “one of those properties that make other deals nervous.”

We signed papers. We picked finishes that felt like joy. We hired contractors who listened. We built without telling anyone who wasn’t on the team. Leo took pictures of me in a hardhat making decisions about tile as if that were as heroic as a wedding dress. Maybe it was.

And then my parents skipped my wedding, and my thirst for gentleness caught fire instead.

My parents’ lives are measured in metrics—annual revenue, board seats, columns of numbers that make them feel bigger. Jessica’s social media followers—her own kind of metric—had swelled since her engagement announcement to an attorney whose smile was all incisors. The Boston Business Leaders Gala had been circled on our family calendar since January, not because it mattered to the city, but because it mattered to them.

“Your sister’s wedding is a merger,” my mother had said over Thanksgiving, when she still pretended to taste my cranberry tarts. “Yours was a gathering. That’s the difference.”

Miss Davies is the kind of woman who reads the society pages like a weather report. “If you want a stage they will not be able to ignore,” she said, “use one they believe they own.”

The Gala rotates keynote speakers between men who look good in monochrome and women with strong jawlines who spend their time on panels about breaking ceilings while their male colleagues install new glass. This year, a speaker had canceled. It happens when pilots strike and egos collide.

“We made a proposal,” Miss Davies said, which is what she called dropping into a committee chair’s lap a dossier so irresistible that saying no would look like fear.

Part Two

A week after my wedding, while I was still combing bobby pins out of my hair and learning to share a bathroom with a man who alphabetizes his aftershave, I signed the agreement to deliver the keynote address. I told no one who wouldn’t stand between me and a man with a microphone.

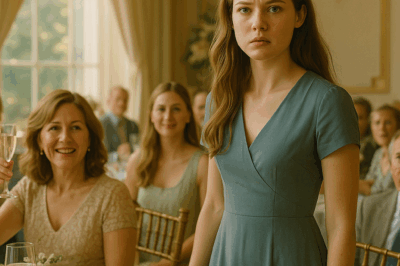

The night of the Gala, the ballroom’s chandeliers did that glittering thing that made everyone look like they’d spent forty-five minutes longer on their hair than they’ll admit. I wore a simple black dress and the necklace Leo’s mother had given me, a tiny gold whisk on a thin chain that made me look down at my sternum and smile.

From the wings, I watched my family take their seats. My father was rehearsing the way his mouth would look when a camera pointed at it. My mother was touching Jessica’s hair like it was a crown. People leaned toward them because they always had; gravity is a habit.

“And now,” the emcee announced, “a keynote from a woman whose work reminds us that innovation is as much about heart as it is about hustle.”

When he said my name, there was a little glitch in the room, like someone had pushed a chair back too quickly. Jessica’s lipstick stopped shining.

I told them a story about an old man in tweed who taught me that sugar is an instrument for memory and about community like a table where everyone belongs. I didn’t say my parents’ names. I didn’t need to. The line I’d practiced until I could say it without trembling came in the middle:

“What my parents call the bottom is where the city meets itself. It’s where hands know work more than words. It’s where excellence isn’t a press release; it’s a pie crust.”

On the big screen behind me, Miss Davies had queued a reveal that made the room—in its tuxedoed, cynical way—gasp. The artist’s renderings of my new patisserie—Alistair’s in gold leaf over a door with beveled glass, a marble counter that made even forks feel honored—filled the screen. Then the Sterling Hotel Group logo slid in beside it.

The contract we’d signed two days earlier granting Alistair’s exclusive dessert partnership with Sterling’s flagship properties hummed under the image like a drum you hear more than see.

Applause roared. It wasn’t polite. It wasn’t even particularly dignified. It was the sound of people suddenly hungry.

I found my parents’ faces. My father clapped because cameras were pointed at him. My mother’s smile had the wrong number of teeth. Jessica’s fiancé pulled out his phone—not to tweet, but to text some man with a contract my father had dreamed of and now might never touch.

After, the CEO of Sterling came to shake my hand. “We’ve been waiting for a reason to say no to your father without saying no to your father,” he said in a tone that ate men like my father for breakfast. “So thank you for your timing.”

“You’re welcome,” I said. “Thank you for the chance.”

The next morning’s headlines made my coffee taste sweeter: The Sweetest Deal in Town: Baker Wins Sterling Contract. The subhead played with the kind of pun that would have made Mr. Alistair roll his eyes affectionately: Bennett family shaken as daughter’s ‘hobby’ goes global.

I did not answer my mother’s frantic texts. I did not take my father’s calls asking to “strategize.” I did not respond to Jessica’s email with the subject line, “Proud of you! Maybe we can incorporate your brand into the wedding dessert table?” If I’d had to reply to one, it would have been to Jessica’s with a menu that consisted entirely of humble pie.

Instead, Leo and I went home and planted rosemary in the clay pot we’d found in a salvage yard the week before. We pushed our hands into soil and came up brown. I set the pot on the narrow sill of the window over our sink. We ate bread and butter for dinner because joy had made us too full for anything else.

The opening of Alistair’s was on a cold morning in February that smelled like snow and yeast. Miss Davies wore red gloves and a look that said she collects moments like this in a secret drawer. The line formed before dawn. Some of the people in it were my neighbors. Some were hotel guests who’d read a blurb in the elevator magazine and had to see if a croissant can make a person cry (it can). Some were women with chapped hands and expensive scarves who wanted to know how to pronounce kouign-amann without swallowing their own tongues.

I tied my hair back and tied my apron and tied my life to a space that felt like the inside of a story I would want to read again and again.

At ten, two people arrived whose names did not need announcing. My parents had dressed for a siege: my father in navy armor and my mother in pearls like bullets. They stood on the threshold and waited for the line to part like a sea. It didn’t. Gravity is a habit, but it can be retrained.

“Clara,” my mother said, when it was finally their turn. Her voice was a knife wrapped in silk. “Congratulations. We’re thrilled.”

“Coffee?” I asked. “Almond cookie?” I held the paper bag out to her like an offering and meant nothing more than that. She took it because she didn’t know how not to.

My father started his speech. I recognized the opening move; he uses it when he wants to look like a patriarch and not a man who cannot control the room. “We should talk,” he began. “About merging your—”

I smiled like service. “We’re all set, thanks.”

“Clara,” my mother said again, and for the first time in my life, my name in her mouth didn’t make me brace. “We love you.”

I thought about the email. The “trivial event.” The ellipsis-elegant insult. I thought about Alistair’s napkin. I thought about the boy in line behind them whose nose barely reached the counter and who would remember if this room made him feel like he belonged.

“I love the people who show up,” I said. “You’re welcome to be them.”

We stared at each other over the counter for one more beat than is comfortable. Then a woman behind them cleared her throat and said, “Can I get four pain au chocolat before the women’s shelter closes for breakfast?” and the world arranged itself into what mattered.

They stepped aside. The line moved. Leo slid a tray into the case and mouthed, You okay? I nodded.

At noon, a delivery arrived we hadn’t ordered: a single white lily, a card with Mr. Alistair’s steady handwriting in copy.

The oven remembers everything you feed it. So does the world. Bake accordingly.

We hung the card behind the counter where only we could see it.

A week after we opened, a little girl in a sparkly coat ate a lemon tart and declared it “happy in my mouth.” Her mother laughed, then cried, then bought one to take to the nurse at the clinic who’d held her hand through a long night. I put two in the box and told her the second was on us. She tried to argue. I slid the lid shut and handed her the ribbon.

On a Tuesday morning when the snow came down like sifted sugar, a man who works nights emptied his pockets and came up with coins and an apologetic shrug. “Pay-what-you-can Wednesday is tomorrow,” I said, “but rules are gentler than people,” and passed him a cinnamon roll large enough to make his palms look small. He said my name like a benediction.

A month later, Sterling’s flagship property launched our dessert menu with a photograph that made strangers send me messages that said, “My god, that mille-feuille.” My parents were at the gala, of course. I wasn’t invited. I was busy tempering chocolate until it shone like a good day.

We took the money that came and didn’t break it into smaller pieces as a dare to our future. We hired interns and taught them how to read recipes the way you read a map. We posted a sign in the window that said, If you’re hungry and broke, knock twice; we have a sandwich. We ordered an extra stool because the first time Mr. Alistair’s son visited, he looked around and said, “It feels like my father would sit and read here,” and then he did.

Sometimes success is a headline. Sometimes it is a cash register that balances. Sometimes it is a quiet moment when you realize you no longer instinctively flinch at your phone.

I do not know if my parents will come to love my work for itself. I do not need them to. Boundaries are built like bakeries: measure, mix, proof, bake, cool. You cannot rush cooling. You cannot hold a hot pan and not expect to be burned. You cannot pull a cake out of the oven before the center is set and expect it to stand.

The center of my life is set.

At night, Leo and I stand in our tiny backyard, dirt under our nails, rosemary stubborn in winter. He kisses me with flour on my jaw and says, “You did it.” I kiss him back and say, “We did.”

Sometimes I teach classes at Alistair’s and a teenage girl with ink on her fingers asks, “How did you know you were ready?” I tell her the truth: I didn’t. I jumped because I found something that looked like a bridge and then built it while I was already over the water.

A year to the day after my parents skipped my wedding, they came to Alistair’s again. They stood in line. They ordered coffee. My father reached into his pocket the way men do when a bill is due. The total was $6.50.

“On the house,” I said.

He blinked. His mouth did something it had not done with sincerity in years. “Thank you,” he said.

My mother did not try to hug me. She did not attempt a speech. She unfolded the bag like a ceremony and took out the almond cookie Mr. Alistair always asked for. She broke it in half and handed part to my father. They ate without speaking.

As they turned to go, she paused. “The rosemary is thriving,” she said, looking at the plant on the sill. “It’s stubborn that way.”

“So am I,” I said.

They left. The bell on the door made its small, familiar sound. The line moved. The espresso machine hissed its agreeable hiss. Sarah texted a photo of a bride at our pastry case, pointing to a croquembouche like a Christmas tree made of cream puffs.

You’re catering Jessica’s wedding? she’d asked a week earlier, half horror, half delight.

No, I’d replied. Jessica is buying desserts from a business she cannot publicly pretend she hates. That is its own kind of meal.

In the afternoon lull, I pulled out my phone and scrolled—not through my mother’s emails, not through Jessica’s life-in-photos, but through the notes app where I keep all Mr. Alistair’s old napkins.

You cannot control who shows up to clap for you. You can control the work.

I slid the phone back into my pocket, washed my hands, and reached for a bowl. Flour. Sugar. Butter cold enough to bite. I cut the butter in until it looked like a storm. I added water until it looked like a promise.

The oven took the pie with a hum like a satisfied old man. The timer winked at me. Leo walked in from a delivery with pink cheeks and a grin that makes me believe in spring.

“Table three just called your lemon tart ‘a small miracle,’” he said.

“They’re not wrong,” I replied, and set the next crust to rest.

Outside, Boston was doing what Boston does—pretending at severity while softening at the edges for those who look closely. Inside, my life no longer needed anyone’s applause. It was built on work and grace and the stubborn belief that what people call the bottom is often just ground firm enough to build on.

My parents thought skipping my wedding would make the ground fall away beneath me. It did the opposite. It showed me exactly how solid it was.

END!

News

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… CH2

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… Part One I…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited me Over Just to Tell me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited Me Over Just to Tell Me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her …

At My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. CH2

My Sister’s Engagement Dinner, Dad Gave Her the Deed to the House I Paid Fifty Thousand Dollars.. Part One…

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And then.. CH2

My Sister Screamed, “Pay the Rent or Get Out!” — She Didn’t Know the House is in My Name. And…

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a… CH2

My Sister Chose Her Husband’s Birthday Over Our Mother’s Funeral_And Now She Came to Me With a … Part…

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration. CH2

My Mom Toasted My Sister’s Glory—Then I Stood Up and Exposed Their Lies at Her Big Celebration Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load