My parents skipped my baby’s birth for a Barbecue—I made sure they never forgot what they missed

Part 1

It started like any other uneasy bargain between my body and the clock.

The house was soft and dark and holding its breath. The ceiling fan hummed overhead, looping lazy circles in the air like it had been told this was sacred ground and to move quietly or not at all.

I was 39 weeks and four days pregnant. All center of gravity and swollen ankles, an overripe moon doing its best impression of a human woman. Sleep hadn’t really been a thing for weeks—just long, shallow dips in and out of discomfort.

That night, sleep was a rumor I didn’t even bother chasing.

At 2:40 a.m., something shifted.

It wasn’t dramatic. Not yet. No Hollywood gush of water, no scream. Just a dull ache uncoiling deep in my lower back, the kind you’d blame on a bad chair or a long day. I lay still and tried to bargain with it the way people bargain with parking tickets and hurricanes.

Not yet. Maybe tomorrow. Let me have a few more hours.

The ache answered with a second wave, tighter, truer. My belly clenched all the way across, the skin drawing in like someone had pulled an invisible string through the center of me.

This contraction had punctuation.

I stared at the digital clock on the nightstand—2:42 glowing in the dark like a tiny red verdict.

“Jacob,” I whispered.

He didn’t move. My husband could sleep through fireworks, thunderstorms, and at least one kitchen fire. But he couldn’t sleep through the sound my voice made on that second “Jacob.”

He bolted upright like someone had yanked him up by an invisible rope. His hair was smashed into patterns no comb could predict. For a moment he just stared at me, pupils huge in the dim light, like he was trying to take inventory of all my parts at once.

“Is it…?” he asked.

Another contraction rolled through, no longer shy about its intentions.

“It’s time,” I breathed, grabbing his hand, because if I didn’t hold onto something I felt like I might float away.

People joke about how you can’t really be ready for birth. We weren’t. But we had rehearsed—mentally, verbally, in bulleted lists on the fridge—what we would do when the moment came.

It was almost funny how smoothly we moved, two sleep-drunk humans suddenly running on adrenaline and muscle memory.

Jacob: grabbed the go bag, double-checked his phone and my charger, threw on jeans and the first T-shirt he could reach.

Me: swung my legs over the side of the bed, paused through another contraction, texted my OB, then my parents, all on pure instinct.

We’re on our way to the hospital. It’s time. Please come.

I hit send and felt a little bubble of something rise up in my chest. Hope is stubborn that way. No matter how many times reality stomps on it, it finds a way to inflate.

My parents live twenty minutes away—fifteen if my dad “just catches all the lights,” as he likes to brag. They’d said they wanted to be there. My mom had talked about pacing the waiting room like the grandmothers in old movies. My dad had said he’d bring his “good camera.”

“You’re their first grandchild,” my mom had said to my belly at twenty weeks, hand flat on the curve of it. “We wouldn’t miss it for the world.”

The thing about “the world” is that it’s much smaller than people pretend it is. Sometimes it’s a backyard. Sometimes it’s a grill.

The drive to the hospital felt like it existed outside of regular time.

The streets were mostly empty, washed in orange from the streetlights. The stoplights flipped obediently from red to green like they’d been warned this was important business. Jacob kept one hand on the wheel and one hand on my knee, squeezing every time my breath hitched.

“You got this,” he kept saying, as if those three words could build a bridge across the pain. “You’ve got this, Mara. We’ve got this.”

Between contractions, I found myself tilting outside my own body, watching us like a scene in a movie I’d seen once as a kid and never quite forgot.

There we were—a guy in an old college hoodie and a woman in an oversized T-shirt and maternity leggings, heading toward the moment the rest of our lives would pivot around.

This is the moment, I thought.

This is the moment we meet her.

In triage, the fluorescent lights were too bright, the air too cold. The nurse strapped the fetal monitor band around my belly, and the room filled with the roar of our daughter’s heartbeat—a rapid, steady thudding, like a tiny horse galloping over a wooden bridge.

I could’ve listened to that sound forever.

“You’re doing great,” the nurse said, checking my dilation. “You’re at four. We’re admitting you.”

Four. I had never cared more about a number in my life.

As we rolled down the hallway to our room, I checked my phone. My parents hadn’t responded.

It was 3:38 a.m.

Maybe they’re asleep, I told myself. Maybe they didn’t hear the text. Maybe the sound’s off.

I texted again anyway.

Headed into labor room now. I really want you here.

Jacob set my phone on the little tray table next to the bed. Contractions came faster, stronger. The monitor traced their peaks on the paper in messy, sharp mountains.

The pain was…a lot. It felt ancient, like my body had been waiting its whole evolution just to do this one impossible thing. I moaned through it, low and animal, surprised at the sound coming out of my own mouth.

Time melted. Nurses came and went, checking vitals, adjusting sheets, asking questions.

“Do you want an epidural?” one asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Maybe. I don’t know. Ask me again in five minutes, I might want to be shot into space instead.”

She laughed, then went to get the anesthesiologist.

When he arrived, he talked me through every step, voice calm, hands steady. Jacob knelt in front of me, letting me crush his fingers as the needle went in.

“Stare at me,” he said. “Just me. Right here.”

I did. His eyes were the only solid thing in a world that kept tilting sideways.

The epidural dulled the edges of the contractions from knives to blunt force. Still intense, but suddenly survivable. It gave me enough space between waves to check my phone again.

4:57 a.m.

No response.

At 5:13, the screen finally lit up.

My mom.

Oh sweetie, today’s really not a good day. Your brother’s BBQ starts in a few hours. He planned it for weeks and you know how much effort he put in. We’ll come by the hospital tomorrow. So excited for you!

I read it once. Twice. Three times. Each reading peeled another layer of denial off my skin.

Our nurse stepped out to grab more ice chips. Jacob was fiddling with the TV remote, trying to find something distracting enough to fill the spaces between contractions but gentle enough not to make me want to throw it at the screen.

He looked over when the air changed.

“Hey,” he said carefully. “What is it?”

I couldn’t figure out how to make my mouth work. I handed him the phone instead.

I watched his eyes move across the screen. Watched his jaw harden. Watched something in his face close, like a door locking.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” he said quietly.

I let out a sound I didn’t even recognize—part laugh, part choke, part sob.

“I told you,” I said, the words oddly calm as they fell out. “Ethan’s the sun. We’re all just planets trying not to burn.”

It wasn’t like I didn’t know the choreography of my family.

I was born three years after Ethan. My parents liked to joke that they’d “gotten all their practice mistakes out of the way” with him before I came along, but that wasn’t how it played. Not really.

Ethan was the center of every room from the beginning.

When he flunked out of his state college sophomore year, my parents called it “a bad fit” and transferred him to a smaller private school two hours away, paying the tuition without a word about budgets.

When he quit his first “real job” five months in because his boss had the audacity to ask for deadlines, they covered his rent for nearly a year. “We help our own,” my dad said. “Family first.”

When I brought home straight A’s, they said “good job” and asked if I’d reminded Ethan about his dentist appointment.

When I got a scholarship offer to a school three states away, my mother sighed and asked if I was sure I wanted to “abandon them.” When Ethan moved across the country on 48 hours’ notice for a gig in a band that never actually played a show, they threw him a going-away party.

Some kids grow up with parents whose love feels like the sun—warm, consistent, always there. I grew up with a spotlight that moved mostly in one direction. Sometimes it brushed me, too, and those moments felt like salvation. The rest of the time, I learned to glow on my own.

But this—this wasn’t just another missed recital or forgotten science fair.

This was my daughter’s first breath.

This was the cliff edge between before and after.

This was abandonment on purpose.

The contraction monitor beeped softly as another wave built. My body clenched, then released, the world narrowing to breath in, breath out.

Labor is a tunnel. You can’t back up. You can only keep going forward, no matter what waits on the other end.

I tried to imagine my mother’s hand cool on my forehead, the way it had been when I’d had the flu in tenth grade and she’d stayed home from work to change my sheets and make me toast.

I tried to imagine my dad pacing the hall, asking the nurse questions like he was gathering intel for some enormous, delicate project.

Keeps your mind off the scary part, he would’ve said, if he’d been there.

They weren’t.

The nurse came back with ice chips and an apology for the delay. Jacob held the cup for me, his fingers brushing my lips.

“Do you want me to call them?” he asked.

“No,” I said. The word surprised me with how solid it was. Like something heavy placed just-so on a shelf. “No. I know exactly where they are.”

On a plastic folding chair. In my brother’s backyard. Pretending smoke and sauce were worth more than this.

The hours rubbed the edges off the clock. The room’s light shifted almost imperceptibly as day crept along outside without us. Nurses changed shifts. The OB stopped in twice, once with a reassuring smile, once with a more serious look and the words “we might need to think about options if things don’t progress.”

They did. Eventually.

Around 4:45 p.m., my OB checked again and grinned.

“You’re at ten,” she said. “It’s go time, Mom.”

Mom. The word landed differently now.

Pushing was its own kind of insanity. The epidural took the sharpest edges off, but the pressure felt like someone was trying to push a planet through a keyhole. I bore down, gripping Jacob’s hand so hard I worried I’d break something.

“You’re doing so good,” he kept saying, voice choked. “She’s almost here. You’re so damn strong, Mara.”

I yelled. I cried. I cursed every ancestor who’d decided this was how humans should reproduce.

And then at 6:22 p.m., she arrived.

Our daughter came into the world with a scream that sounded not scared but furious, like she was personally offended by the entire concept of air.

They placed her on my chest, and the universe narrowed to her weight—warm and damp and impossibly small. Her hair was dark, slicked to her skull. Her skin was mottled red and perfect.

Ara, I thought.

We’d picked the name months ago. Short for Aradia, for the constellation Ara—the altar—and because I’d once read that in some old myths it meant “lioness” and “prayer” and “sky.”

It was also, selfishly, close enough to “Mara” that I hoped she’d never feel like we existed on separate planets.

“Hi, Ara,” I whispered, voice shredded. “Hi, baby. I’m your mom.”

She blinked up at me with unfocused eyes, then rooted blindly, cheeks searching for the shape of me. Someone guided her toward my breast, and instinct did the rest.

Relief hit me like a tidal wave from a direction I hadn’t expected. Relief that she was here. That she was breathing. That the long, terrifying, mystical ordeal was over.

And under that, like a dark tide swirling beneath the surface, a sharper grief:

They missed this.

My parents missed this.

I cried then. Not the polite movie tears, not the single cinematic drop sliding down a cheek. Full-on, ugly, heaving sobs that shook my shoulders.

I cried for joy. For disbelief. For the tiny life on my chest.

And I cried for the empty chairs in that room.

When I finally slept, it was the sleep of a body that had moved mountains and needed, desperately, to lie down.

Jacob called my parents that evening, standing just outside the door of our room, voice low but carrying.

“She’s here,” he said. “Ara. Six pounds, eleven ounces.”

There was a pause. I imagined my mom’s voice on the other end, high and bright, saying something like Oh my gosh, we knew it would be today.

“You missed it,” Jacob added after a beat.

Another pause. His jaw clenched.

“No,” he said, glancing through the little window at me as I dozed, Ara curled against my chest like a comma in a sentence I hadn’t finished yet. “She’s not ready for visitors. She doesn’t want to see anyone right now.”

He hung up and came back in, eyes shining.

“Was that mean?” he asked quietly.

I shook my head.

“No,” I said. “It was true.”

Part 2

We stayed in the hospital two nights.

Two nights of beeping monitors and nurses who moved like benevolent ghosts, checking vitals, slipping in and out at impossible hours with pain meds and fresh water. Two nights of learning how to get Ara to latch, of panicking every time she slept longer than two hours, of staring at her and thinking there is no way they let us take this person home without a license.

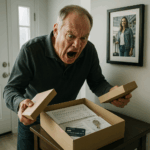

On the third morning, just after a nurse had guided me gingerly into the shower for the first time since birth, the unit clerk knocked on the door.

“Delivery for you,” she said, pushing in a gift bag decorated with pink balloons and teddy bears.

My stomach dropped.

The tag hanging from the handle said, in my mother’s handwriting: For our sweet Ara (and our brave Mara).

I reached in.

A soft teddy bear—neutral beige, with a bow around its neck that smelled faintly of whatever cologne the mall had decided would move the most units that week.

A pack of onesies with generic star patterns and slogans like Dream Big! printed across the front.

A handwritten card.

Congratulations! We are so proud of you. Can’t wait to meet her. Sorry we missed it. Ethan’s BBQ was amazing—he made those ribs you love. Talk soon.

—Mom & Dad

I stared at the words “ribs you love” until the letters blurred.

There’s something obscene about barbecue in a sentence with your child’s first breath.

My hands shook.

Jacob hovered near the bed, eyes flicking between me and the bag.

“What’s it say?” he asked.

I handed it to him without a word.

He read. The muscle in his cheek ticked. He put the card back in the envelope as if it were something toxic.

“You don’t have to answer,” he said. “Not now. Not ever, if you don’t want to.”

I didn’t answer.

Instead, I turned back to Ara, who was making tiny sleep noises, her lips twitching as if she were dreaming about eating.

Her entire world was within arm’s reach—warmth, milk, heartbeat. She had no idea what had happened outside these four walls.

It hit me then, with the force of a contraction:

She doesn’t have to grow up thinking this is normal.

She doesn’t have to learn the calculus of how much of herself to shrink to fit in the leftover spaces.

She doesn’t have to inherit my invisibility.

I lay back against the pillow and let that thought settle into my bones.

When the discharge paperwork was finally done and the nurse handed us the folder of instructions that looked suspiciously like it had been printed in 1997, we wheeled Ara out to the car in a bassinet that looked both hilariously small and terrifyingly precarious.

Sunlight felt sharper than I remembered.

Jacob installed the car seat with a kind of grim focus, triple-checking every latch. Ara scrunched her face as we buckled her in, emitting a complaint that sounded more like a squeak than a cry.

On the drive home, my phone buzzed repeatedly from the diaper bag at my feet.

I didn’t check it.

Home had never seemed smaller and more overwhelming.

The nursery we’d painted a soft green looked suddenly inadequate—too small, too fragile, too tidy for this enormous, messy miracle who had moved into our lives.

Our neighbors, the Patels, had taped a congratulations banner to our door. A casserole waited in a cooler with a Post-it in Mrs. Patel’s tidy handwriting: “Heat at 350 for 30 minutes. Eat the whole thing. Do not return the dish until you’ve rested.”

Rest.

That first week, rest was a myth, but kindness was a fact.

Friends dropped off meals and quietly left. Jacob’s parents flew in from Texas, swept Ara into their arms, and cried in unison like a coordinated sprinkler system. They cleaned our kitchen unasked. Jacob’s mom sat with me at 3 a.m., holding Ara while I cried over nothing and everything.

“Postpartum hormones,” she said gently, stroking my hair. “They’re little terrorists. They’ll even out.”

My parents sent texts.

Can we visit today? We miss her already.

Miss her.

They hadn’t met her.

They missed the idea of her, the dream of being grandparents the way people miss a vacation spot they saw in a magazine.

No visits yet, I typed back once. We’re still settling in.

R u mad? my mom responded. It was a typo she never would’ve made before she discovered emojis.

I stared at the little letters.

I thought about typing No, it’s fine, it was just bad timing. The way I always did—paving over hurt with politeness, smoothing it down like a wrinkle in a tablecloth.

Instead, I put the phone face down on the coffee table and answered Ara’s cry instead.

The calls started on day five.

The first was my mother’s ringtone—some generic marimba that made my skin crawl.

Jacob looked at the screen, then at me.

“I’ll get it,” he said.

He stepped into the bedroom and closed the door behind him.

I could hear only muffled sounds, tones more than words. His voice rose once, then dropped. There was a pause. Then:

“She’s not ready,” he said. “No, she’s not overreacting. She just gave birth. You chose not to be there. That has consequences.”

Consequences.

I liked the firmness of that word.

Later, my brother called.

“Wow,” he said immediately, not even pretending with a hello. “You really going nuclear over this?”

I almost laughed.

“Nuclear?”

“Come on, Mara,” he said. “It was just bad timing. Mom and Dad had been planning the BBQ for weeks. Dad rented one of those big smokers. People came from all over. You know how much work he put in. You can’t expect them to just bail on everyone last minute.”

“Ethan,” I said, feeling a calm I absolutely did not feel, “are you seriously telling me our daughter’s birth was less important than your ribs?”

“It’s not about the ribs,” he snapped. “It’s about commitments. You can’t just expect the world to revolve around you because you decided to have a baby.”

I stared at Ara, who was lying in her bassinet, making quiet little grunts like she was trying out her voice.

“I didn’t expect the world to revolve around me,” I said. “I expected my parents to show up for their granddaughter.”

“You’re being dramatic,” he said. “You’re going to ruin the family over one bad choice?”

I recognized the tactic. The word “dramatic” had been used on me my entire life as a tranquilizer gun, designed to drop me in my tracks. Don’t make trouble. Don’t make noise. Don’t make us feel bad.

But now there was someone else in the room—someone whose entire life would be shaped by what I accepted.

“This isn’t about one bad choice,” I said. “It’s about a lifetime of them. And I’m not going to pretend it didn’t happen just because it makes you uncomfortable.”

He said something about “not making things worse.”

I hung up.

Not because I was furious.

Because I was done auditioning for a role I never wanted: the reasonable one, the forgiver, the family glue.

That night, after Ara finally fell asleep for more than twenty minutes at a time and the apartment was wrapped in that fragile, middle-of-the-night quiet, I sat at the kitchen table with a notebook.

I wrote my parents a letter.

I didn’t scream on the page. Didn’t swear. Didn’t dramatize.

I told the truth like I was giving sworn testimony.

I told them what it’s like to labor without your mother’s hand to hold. The bright cold of the room, the way your own breathing sounds too loud, the strange comfort of strangers calling you “Mama” because no one else in your life is.

I told them about the moment they placed Ara on my chest, and how I looked around the room almost reflexively for them and found no one.

I told them about Jacob saying, “You missed it,” and how that sentence felt like both a wound and a diagnosis.

I reminded them of my text. 3:12 a.m. It’s time. Please come.

I quoted my mother’s text back to her: Today’s really not a good day. Ethan’s BBQ starts in a few hours.

I wrote, in simple black ink, the sentence that had been forming in my chest since Ara’s first cry: From now on, I choose Ara over anyone who didn’t choose us.

I didn’t ask for an apology.

I didn’t ask for anything.

I finished with: I’m not closing the door forever. But I am closing it on pretending.

I mailed it the next morning, one-handed, Ara tucked into the carrier against my chest. The woman at the post office smiled at Ara and stamped the envelope like she was officiating something sacred.

A few days later, there was a knock at our front door.

I peeked through the peephole and saw my mother on the porch, clutching another gift bag.

She looked older than I remembered. Bruises of exhaustion shadowed her eyes. Her hair was pulled into a ponytail that had lost the battle with humidity.

She knocked again, softer.

“Mara?” she called. “Honey, it’s me.”

I stood behind the curtain, heart pounding, Ara’s warm weight snug against my chest.

Part of me ached to open the door. To let her in, to fall into her arms and let her stroke my hair and say all the things she hadn’t said.

But what would I be teaching Ara?

That you can skip the hardest days in someone’s life and still be granted front-row seats?

That apologies, when they came, washed away any need to change?

I stayed still.

“Mara,” my mom said again. “Please. We just want to see the baby.”

We. Meaning her and my father, who sat in the car at the curb, hands clenched on the steering wheel, staring straight ahead.

Ara sighed in her sleep, a tiny sound that felt bigger than the world.

I matched my breathing to hers. In, out. In, out.

After a long minute, my mother’s shoulders slumped. She tucked a small envelope into the gap of the doorframe, hung the gift bag on the knob, and walked back down the steps.

They drove away.

I watched until the car turned the corner and vanished. Only then did I open the door.

Inside the envelope was a card with a printed poem about “new beginnings” and “forgiveness.”

At the bottom, in my father’s neat engineer handwriting, a sentence: We made a mistake. But we’re family. That has to count for more.

I stared at it until the words blurred.

Then I slipped it back into the envelope and put it in the box with Ara’s hospital bracelet and first hat. Not because I wanted to keep it. Because I wanted a record.

The weeks blurred into a collage of small salvations.

Mrs. Patel bringing over steaming bowls of dal and insisting we feed ourselves before we washed the dishes.

Our friend Sam coming over and installing blackout curtains in the nursery with the focus of a professional stagehand, then crying when Ara gripped his finger in her tiny hand.

Jacob’s parents sending us frozen meals labeled with cooking instructions and hearts.

None of them were perfect. None of them were obligated.

But when we needed them, they showed up.

My parents sent a Christmas package—blanket embroidered with “ARA” in loopy cursive, onesies that said “Grandma’s Favorite” and “Grandpa’s Little Grill Master.”

The note said, Let’s put this behind us. We love you. We love her. Please.

I mailed the blanket back with my original letter and, at the bottom, one extra line: You had one chance to witness her first breath, and you chose burgers and lawn chairs.

People expect revenge to be loud.

Screaming matches on front lawns. Social media call-outs. Dramatic confrontations that leave shattered glass and stunned neighbors.

I had…no bandwidth for that.

I was too busy keeping a tiny human alive on three hours of broken sleep and whatever food I could eat with one hand.

But I had promised myself something in that hospital room.

I will make sure they never forget what they missed.

And promises, I was learning, are only as real as the plans you build under them.

Part 3

The idea came to me at 3:07 a.m., in the dim blue of the baby monitor, with Ara latched at my breast and her free hand resting on my collarbone like a tiny claim.

The TV was on mute, throwing silent color against the wall. Jacob snored softly in the bedroom, the sound of a man who had changed twelve diapers in twenty-four hours and earned every decibel.

On the coffee table, my phone lay facedown.

I could’ve scrolled. Could’ve checked notifications, doom-scrolled parenting blogs, googled “is it normal if baby does X.”

Instead, I stared at the blank slate of the wall and thought about memory.

My parents would forget.

Not in the big sense—they’d always know, somewhere, they’d missed Ara’s birth. But humans are talented at revision. They’d smooth the edges over in their minds, sand down the specifics.

They’d remember it as a scheduling problem, a misunderstanding. Not a choice.

I didn’t want to punish them. Not exactly.

I wanted to remove the option of rewriting.

Some truths don’t need volume. They need archiving.

By 3:45 a.m., I had a plan.

The next afternoon, when Ara finally surrendered to a nap not on my body but in the bassinet like a miracle, I opened my laptop at the kitchen table.

Jacob was hunched over the sink, washing bottles, humming some nonsense song he’d made up about burp cloths.

“What are you doing?” he asked, drying his hands on a dish towel when he saw me frowning at the screen.

“Making a book,” I said.

He paused. “Like a baby book?”

“Kind of,” I replied. “But not the usual kind. This one’s not for her. It’s for them.”

I pulled the photos off his phone—the ones from the hospital he’d taken in shaky, awe-struck hands.

Me on the bed, hair a disaster, face flushed and streaked with tears, eyes wild and joyous.

Ara on my chest, skin mottled, hat too big, mouth open in outraged protest.

Jacob standing by the bassinet, one hand reaching in, expression halfway between laughter and a meltdown.

The heart rate monitor showing 6:22 p.m. in green numbers.

The little whiteboard where a nurse had written “Welcome, Ara!” and added a smiley face.

I uploaded them to a photo book website, each image a stepping stone across a day that had already started to blur in my head.

Then I added the screenshots.

My text at 3:12 a.m.: It’s time. We’re headed to the hospital. Please come.

My mom’s response at 5:47 a.m.: Today’s really not a good day. Ethan’s BBQ starts in a few hours. We’ll come tomorrow.

I put them on a page by themselves. No commentary. Just the black text bubbles against a white background.

Underneath, in small, simple font, I wrote: This was your RSVP.

On another page, I scanned the card from the gift bag. Congratulations… Ethan’s BBQ was amazing—he made those ribs you love.

I highlighted that sentence.

Under it: This is the only time in her life her birth and your menu will share a page.

Jacob leaned over my shoulder.

His eyes moved across the screen, his face shifting through anger, sadness, a kind of bleak amusement.

“Damn,” he said softly. “That’s…cold.”

“I’m not trying to be cruel,” I said. “I’m trying to be accurate.”

He wrapped his arms around my shoulders from behind, resting his chin on my head.

“I’m not saying you’re wrong,” he said. “I’m just glad you’re on our side.”

I kept going.

On the last page, I put a photo of Ara asleep on my chest, our skin touching, my hand cupping the back of her head.

Underneath, I wrote: Every year on this day, we celebrate the choice we made to show up for her. We hope one day you celebrate yours.

For the cover, I chose matte black. No cute baby pastels. Just black, with silver letters:

THE DAY YOU MISSED

Ara’s First Hours

On the dedication page, I wrote:

For the grandparents who weren’t there.

Our door is open to those who arrive.

In the shipping details, I set the address to my parents’ house and checked the box that said “Repeat every year.”

Jacob watched as I hit “Order.”

“You’re really doing this,” he said.

“Yes,” I said.

“Every year?”

“Every year,” I confirmed. “As long as it takes.”

He was quiet for a moment.

“Is this for them?” he asked. “Or for you?”

I thought about that.

“Both,” I said finally. “And for her. So she never has to wonder if she was wanted. There will be a whole shelf of proof.”

The first copy arrived a few weeks before Ara’s first birthday, in a plain cardboard sleeve.

I opened it at the counter, smoothing my hand over the matte cover. It felt heavier than it looked.

I flipped through the pages. The story unfolded in pictures and text bubbles and captions, a day distilled into ink.

Jacob looked over my shoulder, let out a breath.

“You really did it,” he said.

Ara, sitting in her high chair, banged a spoon against the tray and shrieked happily at her own echo.

“We’ll send it on her birthday,” I said. “Happy anniversary of the thing you skipped.”

On the morning Ara turned one, we decorated the apartment with cheap balloons and streamers that refused to tape to the wall without a fight.

Jacob’s parents FaceTimed in from Texas with party hats on, singing “Happy Birthday” off-key. Mrs. Patel brought over a plate of laddoos and insisted Ara try a tiny bite. Our friend Sam took a hundred pictures of Ara smashing cake with both hands, frosting smeared across her cheeks like war paint.

Between the chaos and the sugar and the tears I hadn’t anticipated—because how could she be a whole year old already—I slipped out onto the porch, book packaged, address written, stamp affixed.

I slid it into the mailbox. Let the metal door clang shut.

In case you forgot, the note inside said.

My mom texted that night.

We got your book. You didn’t have to do that. We said we were sorry.

She hadn’t, actually. Not in any way that sounded like the word “I was wrong” without qualifiers.

I stared at the three little dots that appeared as she typed something else, then disappeared, then appeared again.

I put my phone on airplane mode and went back inside, where Ara was attempting to pull Jacob’s nose off his face.

The second book went out the next year.

By then, Ara was toddling—those wide, wobbly steps toddlers take like drunk little astronauts. She could say “Mama,” “Dada,” “up,” and “no” with alarming confidence.

On her second birthday, we threw a small picnic at the park. Jacob’s parents flew in, Sam brought his new boyfriend, Mrs. Patel wore a sari that glittered in the sun and brought an entire Tupperware army of snacks.

We took a photo of Ara running toward the camera, curls flying, eyes lit up with mischief.

That night, I printed it and taped it inside the front cover of the second volume before shipping.

Under it, I wrote: This is what you missed this year.

No response.

The third year, Ara fell off the slide at the park a week before her birthday and split her chin open. She screamed, I screamed, Jacob carried her to the car like a football while I pressed a towel to her chin and tried not to faint.

At urgent care, the nurse coaxed her into sitting still for three tiny stitches by letting her hold a glittery sticker.

“Scars are just stories your body remembers,” I told her afterward, kissing the bandage.

On her birthday, I included a photo of her showing off the scar proudly, chin tilted up, bandage gone, a faint pink line there if you looked closely enough.

Caption: She’ll always remember who held her when it hurt.

I sent the third book.

Three days later, a box came back.

Inside were all three volumes, still in their shrink wrap.

No note.

No explanation.

No sign they’d even opened them.

Jacob opened his mouth, then shut it.

“What?” I asked.

“I was going to say ‘at least they’re honest about not wanting to remember,’” he said. “But that feels…wrong, somehow.”

I picked up one of the books. The plastic reflected my face back at me, warped and shiny.

“They don’t want the reminders,” I said. “They want the right to pretend they were there.”

I stacked the books on the shelf next to Ara’s toys.

“Then we’ll keep them,” I said. “She can decide what to do with them when she’s older.”

In the shipping settings, I changed the address.

From then on, a new book arrived each year at our address instead. I’d still write the note—In case you forgot—and tuck it inside, but I stopped paying postage to hand them the truth they were too scared to open.

Instead, the shelf in our living room slowly filled with matte black spines:

The Day You Missed: Year 1

Year 2

Year 3

Each volume contained the story of that birthday and the year before it.

Ara’s first steps. Her first word (which, for the record, was not “Mama” or “Dada” but “cookie”). The day she fell in love with dinosaurs. The night she woke up from a nightmare and climbed into our bed, pressing her cold feet into my thighs and whispering, “You’re here, right?”

On the last page of each book, I wrote a note addressed not to my parents, but to her:

You were always worth showing up for.

By the time Ara turned four, she’d noticed the books.

“What are these?” she asked one rainy Saturday, running her fingers along the spines.

“Those,” I said, “are stories about your birthdays.”

“Like a baby book?”

“Sort of,” I said. “But…different. We can read them together when you’re a little older.”

She frowned, considering this, then shrugged and went back to building a castle out of blocks and plastic dinosaurs.

The thing about vengeance is that people expect it to taste hot, like fire.

This didn’t.

It tasted cool. Clean.

It tasted like the relief of knowing that no matter what anyone else remembered, we had receipts.

Part 4

The first time Ara asked directly about my parents, she was five.

We were at the park on a Sunday afternoon. Jacob was pushing her on the swing, and she was shrieking “Higher! HIGHER!” in the way that makes every parental instinct you have fight with the joy on her face.

On the bench, I sat next to Jacob’s mom, who had flown in for the weekend.

“Back in my day,” she said, watching Ara, “we just put y’all on a tire hanging from a tree and hoped it didn’t snap.”

“Great,” I said dryly. “Truly helpful image, thanks.”

After a while, Ara hopped off the swing and ran over to us, cheeks pink, hair sticking to her forehead.

“Grandma,” she said, plopping herself in my mother-in-law’s lap. “Why do you live far away?”

“Because your grandpa and I are silly and decided to live where it’s too hot,” she said, booping Ara’s nose. “But we come whenever we can.”

Ara nodded, satisfied with this logic. Then she turned to me.

“Do I have other grandparents?” she asked.

It felt like someone had dropped something heavy into my chest.

“You do,” I said carefully. “My mom and dad.”

“Where are they?”

I took a breath, feeling the familiar urge to soften the truth, to make it easier to swallow.

Then I remembered a baby in a hospital room and empty chairs.

“They don’t live far,” I said. “But…they made some choices that hurt me. And they weren’t there when you were born. So I decided they don’t get to be part of our life right now.”

She thought about that, brow furrowed in serious five-year-old contemplation.

“They chose not to come?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “They chose a barbecue instead.”

Her eyes widened. “Like hot dogs?”

“And ribs,” I said. “And burgers. And all the food in the world isn’t as important as the people you love.”

She nodded solemnly.

“Do you miss them?” she asked.

The question landed softer than I’d expected.

Sometimes, in the quiet hours, I did. I missed the idea of them—the parents I’d wanted, the ones who would’ve shown up. Not the ones who actually existed.

“Sometimes I miss what I wish I had,” I said honestly. “But then I look at who’s here, and I feel really lucky.”

Ara looked at her grandma, at Jacob on the swing, at Mrs. Patel waving from a nearby bench.

“We have enough people,” she declared, with the blunt certainty of someone whose world is still small and safe.

“Yes,” I said, pulling her into my lap. “We do.”

That night, after we tucked her in and she fell asleep hugging a stuffed brontosaurus, I pulled down the first book from the shelf.

I sat on the couch, thumbing through the pages, tracing the curve of my younger, exhausted face on glossy paper.

Jacob joined me, sliding under my arm.

“You okay?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “She asked about them today.”

His shoulders tensed. “What did you say?”

“The truth,” I said. “Gentle version. But still the truth.”

He nodded, exhaling.

“You’re good at that,” he said. “Telling the truth gently.”

“I had enough years of swallowing it,” I said. “I’m done with that diet.”

The years kept piling up, as they do.

Ara turned six, then seven. She lost teeth. She gained opinions. She wrote her name for the first time on a crumpled piece of construction paper and presented it like a diploma.

We added a new volume to the shelf every year.

On her seventh birthday, we had a party at the roller rink. Jacob laced her skates, wobbling on his own feet as he tried to show her how to balance. She fell at least twenty times, each one followed by a burst of laughter.

That year’s book included a photo of her skating between me and Jacob, each of us holding one of her hands, the three of us out of sync and completely, deliriously happy.

Caption: This is what showing up looks like.

When Ara turned ten, a letter arrived addressed to me in my father’s handwriting.

The return address was my parents’ house.

“I can throw it out if you want,” Jacob offered, holding it with two fingers like it was hazardous material.

“I want to read it,” I said.

We sat at the kitchen table. Ara was in her room playing some elaborate game with her dinosaur figurines and a set of wooden blocks. We could hear her narrating their adventures in a mix of growls and sound effects.

I opened the envelope.

Mara,

We’ve received your “books” every year. We understand you’re angry. We’ve apologized for that day. We can’t change it. We know we made a mistake.

But we miss you. We miss our granddaughter. We don’t think it’s fair to punish her for something she doesn’t understand. We would like to meet her. Just once.

We’re older now. We don’t know how many more chances we’ll get. Please give us one.

Love,

Mom & Dad

I read it twice.

Nothing in my body moved the way it used to at their apologies—not the old rush of hope, not the sick churn of guilt.

I just felt…tired. And very, very clear.

“They still think this is about anger,” I said. “About punishment.”

Jacob nodded slowly. “Isn’t it, a little?”

“Maybe at first,” I said. “But now?” I looked over at Ara’s door, where a sign she’d drawn said “NO BOYS ALLOWED EXCEPT DADA & SAM” in crooked letters. “Now it’s about standards.”

I slipped the letter into the newest book, tucking it into the back cover like a footnote.

On the inside of the front cover, I wrote in neat black ink:

You had a chance. You made a choice. This reminder is yours. Her love belongs to those who earned it.

I mailed the letter and the book back to them together.

They never responded.

Ara found the shelf again when she was twelve.

By then, she’d developed a strong sense of injustice and a deep love of true-crime documentaries, which is a dangerous combination in a preteen.

“What are these?” she asked one Saturday, pulling down the first volume and flipping it open.

“We’ve talked about them,” I said carefully. “They’re about the years they missed.”

She walked over to the couch, plopped down, and patted the cushion next to her.

“Can we read them?” she asked.

“Are you sure?” I asked. “Some of it might make you sad.”

She shrugged. “I’d rather know. Not knowing makes my brain make up worse stuff.”

So we read.

We read about the hospital, about 6:22 p.m., about ribs and barbecues and text messages highlighted.

We read about park picnics and roller rinks and scraped chins and the neighbors who showed up with mangoes and casseroles when I could barely remember my own name.

We read about the time she lost her first tooth at school and how Mrs. Rivera had taped it into a tiny envelope with a dinosaur sticker.

We read the letters my parents had written, their once-bold handwriting a little shakier each year.

By the time we got to Year 10, Ara’s jaw was tight.

“They really didn’t come?” she asked quietly. “Ever?”

“No,” I said. “They sent gifts sometimes. But they never really came.”

She flipped to the back of the most recent book, where I’d written: You were always worth showing up for.

“They don’t deserve me,” she said matter-of-factly.

A surge of fierce protectiveness rose in me.

“You deserve people who know that,” I said.

She nodded slowly, then closed the book and set it back on the shelf.

“You don’t have to keep sending them,” she said. “The books. I know what happened.”

“I know you do,” I said. “But they’re not really for them anymore. They’re for us. So that every year, we take a second to remember what we have. And what we chose not to keep chasing.”

She tilted her head, considering that.

“So it’s like…a reverse birthday present,” she said. “We’re giving ourselves proof.”

I laughed. “Exactly.”

On her thirteenth birthday, after everyone had gone home and the kitchen was a disaster of wrapping paper and pizza boxes, she handed me a small envelope.

“What’s this?” I asked.

“Open it,” she said.

Inside was a photo she’d had printed: the three of us at the beach last summer. I was laughing at something Jacob had said. He was holding Ara piggyback, her arms stretched wide like wings. We were sunburned and sandy and radiating joy.

On the back, in her loopy teenager handwriting, she’d written:

Put this in this year’s book. Underneath, write:

THIS is what you missed. And we’re not sorry.

I hugged her so hard she squeaked.

“You’re savage,” I said.

“Wonder where I get it from,” she replied, smirking.

Years later, when she was packing for college, we stood in front of the shelf again.

There were eighteen volumes now, lined up like a second spine to our family.

“Can I take one?” she asked.

“Any one you want,” I said.

She ran her finger along the spines, then pulled out Year 1.

“Start at the beginning,” she said.

“You sure?” I asked. “You were kind of wrinkly.”

She snorted. “So were you.”

She tucked the book into a box between textbooks and a photo of her and her friends in front of the high school.

As we carried the boxes out to the car, my chest ached and swelled and broke and mended all at once.

I thought of my parents, of the house I hadn’t set foot in for years.

I wondered if they still told anyone they had a granddaughter.

I wondered if, on Ara’s birthday each year, they thought not about the barbecue they’d chosen, but about the books they’d refused to open.

I hoped, in a way that surprised me with its gentleness, that they did.

Not because I wanted them to suffer.

But because some things should haunt you.

After we dropped Ara at her dorm and I hugged her until she laughed and said, “Mom, you have to let go at some point,” Jacob and I drove back home in a quiet that felt enormous.

That night, I sat on the couch and pulled down the newest blank volume I’d ordered—a matte black cover waiting for a title.

I wrote on the spine:

Year 18: The Year She Flew.

On the first page, I taped a photo of Ara with her dorm key, grinning, eyes bright with fear and excitement.

Underneath, I wrote: She is starting a life you don’t know.

On the last page, I wrote, for the nineteenth time:

You were always worth showing up for.

Then, for the first time, I addressed a note not to my parents, but to myself.

Dear Mara,

You showed up.

In every hour, in every decision, in every boundary.

You broke the pattern.

You gave her what you never had.

That’s the only revenge that matters.

Love,

You

I closed the book and slid it onto the shelf.

The room was quiet. The house felt both too big and exactly right.

I thought of my parents, somewhere out there.

I thought of a backyard barbecue twelve years ago, smoke rising, laughter floating, ribs sizzling on a grill while a phone buzzed with a text they chose not to answer.

And I knew, with a calm that ran deeper than anger, that they would never be able to fully forget what they’d missed. Not because I’d sent them books they didn’t read, not because I’d written down the dates and times and words.

But because every joyful photo we posted, every story that reached them through the stubborn grapevine of extended family, every silence when they introduced themselves and no one said “Oh, you must be Ara’s grandparents” would echo the same truth:

When it mattered most, they were somewhere else.

And we—me, Jacob, our daughter, our loud and loving and imperfect chosen family—we were right where we were supposed to be.

Showing up.

THE END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

Don’t Argue With My Wife In Her House! My Son Yelled, Even Though It Was MY House.

Don’t Argue With My Wife In Her House! My Son Yelled, Even Though It Was MY House. PART 1…

“Get me the money by tomorrow!” my father roared, dumping $800,000 of my sister’s debt on me.

“Get me the money by tomorrow!” my father roared, dumping $800,000 of my sister’s debt on me. I stayed calm,…

My Mom Silenced My Selfish Mother in Law and Revealed Her Secrets at My Wedding

My Mom Silenced My Selfish Mother in Law and Revealed Her Secrets at My Wedding PART 1 Hi. I’m…

My brother broke my ribs. Mom whispered, “Stay quiet – he has a future.”

My brother broke my ribs. Mom whispered, “Stay quiet – he has a future.” But my doctor didn’t blink. She…

I Told My Son to Slap His Spoiled Niece Since I Can’t Stand My Husband’s Family, My Husband Then Threatened To Divorce Me.

I Told My Son to Slap His Spoiled Niece Since I Can’t Stand My Husband’s Family, My Husband Then Threatened…

My Mom’s New Boyfriend Grabbed My Phone—Then Froze When He Heard Who Was Speaking…

My Mom’s New Boyfriend Grabbed My Phone—Then Froze When He Heard Who Was Speaking… He called her a “lazy civilian.”…

End of content

No more pages to load