My Parents Said: “You’ll Never Be As Good As Your Brother.” I Just Replied: “Then Ask Him To Pay…”

Part One

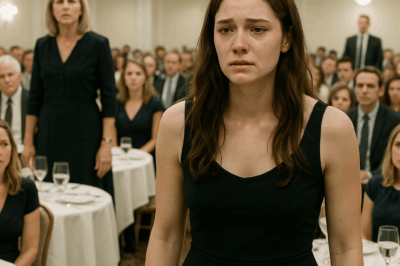

At my mother’s sixty-fifth birthday party—lace doilies under paper plates, daisies from her garden spilling out of a chipped vase, a frosting-smudged “65” candle refusing to stand up straight—Aunt Linda lifted a teacup and said exactly what I’d heard my whole life.

“Chase is such a beautiful son,” she cooed. “Sending money to your parents every month, regular as clockwork. This family is lucky to have him.”

There were nods and humming agreements, the easy music of a chorus that knew its part. My mother turned from the sink with the same proud tilt to her chin I remembered from grade school assemblies. “Alvin,” she said, “why can’t you be even a fraction like your brother? You should learn from him. Chase is the one taking care of this whole family.”

Pamela squeezed my hand under the table. Breathe, her eyes said. Don’t let them in.

But something in me that had been holding since childhood—since Christmas lights reflecting off an LED lamp I’d soldered from junk parts, since a science fair where the front row chairs stayed empty because my brother had a basketball game—snapped neatly. I pushed my chair back. Its legs scraped the floor, a small metallic scream.

“If that’s the case,” I said, voice steady because I’d practiced steadiness my whole life, “from now on, let Chase handle all the bills. I’ll stop sending money.”

Silence fell like a dropped blanket. Even the clock on the wall paused.

My father straightened in his chair, coal-dust lungs pulling a breath for a question he’d never thought to ask. “What money? We’ve never received a cent from you.”

My mother nodded, ready with the script. “Alvin, don’t talk nonsense. You work far away, you barely call. When have you ever sent money?”

Pamela’s thumb found my pulse. I pulled out my phone, opened my banking app, scrolled to a familiar list. The transaction history glowed blue: $2,500 every month, sometimes $2,700, sometimes $3,000, labeled for parents, deposited into Chase G. I held the screen up like a mirror.

“Here,” I said gently. “For the past two years. Every month. To Chase. To give to you.”

Tea cooled. Balloons bobbed shallowly against the ceiling as if trying to rise.

My mother’s hands trembled. She took a step toward me and stopped as if a string had caught. My father’s eyebrows lifted in a V I had only ever seen when he emerged from underground and blinked up at daylight. “Alvin,” he asked, “is this true?”

A hush rolled through the room—Uncle Frank lowering his voice for the first time in years, a neighbor swallowing a comment, Aunt Linda setting her cup down with a tremble—then the hush turned toward my brother.

“Chase?” Uncle Frank said, not unkindly and not softly. “What’s this about?”

Chase sat on the edge of the couch in a navy suit with a watch that threw light across the room. He had the bright, disarming smile he’d used since kindergarten to convince adults that messes cleaned themselves and misunderstood was a synonym for innocent. He opened his mouth and closed it. When he spoke, his voice was small and thirteen. “I—Dad—Mom—I didn’t mean—”

“Speak,” my father said, a miner again, voice stripped down to what still worked.

“I borrowed it,” Chase blurted, words stumbling over each other. “Just for a bit. I was going to pay it back. I gave you some, a few hundred every month so you’d… so you’d think… I mean—” He swallowed. He looked at me and looked away. “I needed it,” he whispered. “For debts. For projects. To keep up appearances. I didn’t want you to be disappointed. I didn’t think it would—” He stopped when the quiet made space for the size of the truth.

All those months slurping ramen in my Austin apartment, all those nights staring at the ceiling because a late bug fix had eaten the hours and a wiring diagram had turned into a language only the tired understood, all those transfers, for parents, widening like ripples into someone else’s new car, someone else’s bar tab, someone else’s watch.

Pamela stood. Her voice was soft and firm, the first light after storm. “Alvin didn’t want to make a big deal,” she said to the room. “He just wanted his parents to live well. He has lived frugally to do it. He worked, he sent money, and he didn’t ask for thanks. But this is not about thanks now. It’s about truth.”

My mother made a sound somewhere between a sob and my name. She stumbled toward me and grabbed my hand with both of hers. “My son,” she said, voice breaking along lines she had never allowed herself to acknowledge. “I… I didn’t know. I am so sorry. I was wrong. All these years—” Her words dissolved. She squeezed my fingers as if to assure herself I was solid.

My father reached for me and pulled me close without rising, coal-nicked fingers rough and shaking. “I thought—” He shook his head once. “I am proud of you, Alvin.”

Aunt Linda stared at the ceiling. Uncle Frank studied his shoes. A neighbor coughed and said, to no one, “Turns out Alvin’s the one carrying the family.” The sentence lodged in the room like a new piece of furniture; no one knew how yet to walk around it without bumping a shin.

Chase sat staring at the carpet as if it might give him a plot twist.

For a long time, my family had been a stage where I stood in the wings, applause trained on the gleam in the center. I didn’t want the center. I wanted a seat. I wanted sunlight without earning it by being someone else. I wanted to love the people in this room without measuring my worth against a brother who had learned that charm repaid faster than debt.

The LED lamp I’d built in eighth grade sat on a dusty shelf in the corner, still faintly glowing when you brought it near an outlet, because some circuits remember the last time they were plugged in. I was done being the bulb no one noticed worked.

“Mom,” I said calmly. “Dad. I love you. I want to keep supporting you. But I can’t continue like before.”

I felt Pamela’s hand on my back, not pushing, just present. I met my parents’ eyes, one after the other.

“From now on,” I said, “there are conditions. No more comparisons. I am Alvin. I am not a percentage of Chase. Second, transparency. I’ll send money directly to you or I’ll pay the bills myself. I need to know where it goes. Third, Chase contributes. If he wants to be part of this, he puts in money, or time, or both. Responsibility isn’t a costume. He wears it, or he doesn’t get to play this part.”

My mother nodded immediately. “Yes,” she said. “Yes. You are right.” Her voice steadied as if the words had given it structure. “No more comparisons. I am ashamed we did that. We were wrong.”

My father looked at Chase. The disappointment had deep roots. He pulled them up without noise. “Son,” he said quietly, “you will make this right.”

Chase lifted his head. His face was red and raw. “I’m sorry,” he said to me. To my parents. To the daisies drooping in the vase. “I was wrong. I was selfish. I wanted to be someone I wasn’t. I thought if I looked like success, no one would notice I didn’t have it. I will pay you back, Alvin. I will take care of—I will try.”

I didn’t know if the promise would hold. I didn’t know yet how to forgive. I knew, suddenly and clearly, how to love without handing over my dignity as proof of admission. Pamela slipped her arm through mine. In the quiet, it sounded like the click of a key turning for the first time in a lock that had been painted shut.

The party stuttered to an end. No one cut the cake. The daisy frosting sweated under the kitchen light. Aunt Linda kissed my cheek and called me “dear.” Uncle Frank muttered something about “proud of you, boy.” A neighbor hugged my mother as if she were a woman and not a pedestal fallen over.

Afterward, in the dim front room with the TV off, Pamela touched the edge of my jaw. “You did something hard,” she said.

“I did something necessary,” I said. “It’s not the same as hard.”

She smiled and the LED lamp flickered as if in agreement.

I had become an engineer because circuits made sense when people didn’t. A line goes here, a resistor there, a path is traced, a signal arrives. My family had never learned to solder. It had taped and hoped. That night, I decided to lay a new trace.

The story that brought me to the daisies began long before I opened my bank app at my mother’s table. It began in Beckley, West Virginia, a small town held together by habit and hills, where my father came home from the mine with coal in the lines of his knuckles, and my mother bragged to neighbors that her youngest son could light a room.

I was the quiet one, fine at school, friend to the library and the old computer my father bought at a yard sale, a boy who understood machines better than he understood applause. Chase was charisma made flesh, able to turn a parent-teacher conference into a fan club meeting. Our teachers told my mother, “Chase is outstanding—always full of energy,” and then turned to me and sighed, “Alvin does fine, but needs to be more outgoing.” My mother nodded as if the praise were for her and the sigh for me.

I didn’t resent Chase. He was my little brother. I built an LED lamp and hoped my parents would like it; my mother told me I should play more. At the science fair, with our model rocket on a folding table under fluorescent lights, I glanced at two empty chairs and told myself maybe they’d be there next time. Next time, a game. I learned to clap for my brother and go home to solder.

In high school I fell in love with code. Hello, world flashed on a screen in the dim computer lab, and the moment felt like a secret handshake with the universe. I applied to West Virginia University for electrical engineering. My acceptance letter shouted where I whispered. My mother said it was “good, keep being independent,” as if independence were a warning label and not a choice.

Chase made a different choice. He dropped out of college after a year because “school wasn’t for someone like him” and chased investments that sounded like TED Talks. He called home to spin plans with capital letters—App, Venture, Partner, Fund. My parents dipped into their savings when he needed “startup costs.” When I called asking for $80 for a required textbook, my mother said, “Things are tight, Alvin. I just sent money to Chase. You’ll have to manage.” I did. Coffee shop shifts, dishwashing, fixing dorm laptops for $20 and a thank-you, tutoring kids who forgot to say thank-you.

I graduated and moved to Austin for a software job. The city made sense because it was a machine—systems and traffic and heat. I rented a small apartment. I sent money home when my mother called and said the roof leaked and my father’s lungs were worse. $2,500 became the monthly number that separated my worry from theirs. Because my parents didn’t trust online banking and because my brother lived near them, I sent the money to him with the note for parents and imagined cash in my mother’s hands, a pill bottle paid for, the roof click-fixed, daisies still blooming.

The number went up when my mother said the pharmacist had shaken her head and the price had risen. I ate fewer dinners out. I tapped confirm with the reflex of habit and the satisfaction of duty. Chase posted a selfie beside an SUV I knew he couldn’t afford. I wrote code. He wrote captions. We both wrote stories we wanted to be true.

Pamela found me because my eyes were tired and she was good at noticing. She worked in marketing down the hall and laughed at how my brain turned everything into a flowchart. She made me eat when I forgot to. She showed up with cookies during a sprint and sat on my couch and taught me to watch a movie without thinking about work. When I told her about the transfers through Chase, she said, “Transparency is love,” and I said, “It’s embarrassment,” and she said, “You are allowed to be seen.” She was the one who held my hand under my mother’s table while Aunt Linda performed admiration at my brother and said, breathe.

Pamela is the reason my voice sounded like a tool and not a weapon when I stood up in that living room. She is the reason I didn’t throw the phone at anyone, the reason I said conditions and not consequences in a tone that made both possible.

After the party, I went back to Austin and did what engineers do. I changed the system.

I opened a joint account with my mother and taught her to read an app, one button at a time. We practiced on a $10 transfer that made her giggle like a girl who had just learned a magic trick. I kept sending $2,500 on the first of the month and asked for a photo of the electric bill when she paid it. She sent one with a note: I’m old but I can learn. I texted back a photo of Pamela’s cookies: Me too.

My parents stopped saying “Chase.” They started saying “Alvin” without the just they had used my whole life. My father called and told me he had told a neighbor that his son was an engineer in the big city. He coughed and said, “I am proud,” like he was learning a new kind of breathing.

Chase got a job at an auto shop because pride is expensive and debts are hungry. He sent Mom $300 in an envelope and stood at the sink and washed dishes without posting about it. He told me on the phone, voice small as the LED lamp on the shelf, “I’m trying.” I said, “Keep trying,” because encouragement was cheaper than punishment and more effective than shame.

Pamela said, “We can be a family that changes.” I said, “Maybe,” and then I watched it happen in small ways that felt like a revolution.

Part Two

A year after the daisy-party bomb, I married Pamela in a small church on the edge of Austin. Sunlight wove itself through stained glass onto wooden pews and people I loved. We hung a strand of white daisies around the bandstand because my mother said they made even a simple day special. The acoustic guitarist played “Can’t Help Falling in Love” as if he had invented love that morning.

My mother wore a pale blue dress and cried during the vows, a soft, breathy sound that used to be worry and was now joy. My father stood up with help and smiled in a way that made me wish I could go back and hand him this day when he was thirty and black-lung free. Chase came in a suit that fit his new salary, hugged me, and said simply, “Congratulations. I’m trying.” It was enough.

Aunt Linda brought a lemon pound cake and said to Pamela, “You are a blessing,” and to me, “You are a good man.” I didn’t know what to do with the second sentence other than say “Thank you” like it was foreign and sweet on my tongue.

Pamela had insisted on small details—handwritten place cards, a wooden photo frame with our names carved into it, daisies tucked into napkin rings—and I had insisted on two things: my mother sat in the front row and we danced to a song she loved. We did. She laughed and called me an awkward boy and a beautiful man in the same breath.

After the wedding, Pamela and I bought a small house with a little plot of dirt big enough to hold a promise. We planted daisies because my mother said they were stubborn in the best way. I wrote code in the morning and came home to the smell of tomatoes roasting and my wife humming in the kitchen. Pamela started a small marketing consultancy; I led a project team. We held hands in the produce aisle like adolescents because we had gotten old enough to not care how it looked.

We visited Beckley often. My mother brought out the camera I had bought her—buttons big as promise, screen bright as a memory—and took photos of Pamela’s hands in the dirt next to her daisies, of my father in his new armchair, of me on the couch showing her how to zoom in. She texted me a photo of an electric bill with a checkmark emoji, then sent three hearts. I sent a picture of the bank transfer confirmation like a matching bracelet.

Chase opened a small garage with a friend. It wasn’t glamorous. It was grease and receipts and a bell over the door that made the same sound whether a paying customer or a beggar walked in. He sent $300 to our parents each month, sometimes more. He took our father to his checkups and sent me updates with too much detail in the way people who choose repair over reinvention do. He called me once and said, “I want you to be proud,” and I said, because it was true, “I am.”

The LED lamp on my mother’s shelf burned out because nothing lasts forever. I took it apart and replaced a resistor. I showed my father the new solder and we both admired how a small, hot bead could hold something together for years. He nodded as if I had explained a mystery larger than it was.

Years passed. The shadow I’d lived under thinned and then simply wasn’t there anymore because shadows need light to shape them and the light in my life had changed. I stood on a dais at a company all-hands meeting and talked about infrastructure and people clapped for my slides. I drove home under a sky that did not ask me to prove I had earned it. I walked into a kitchen where a woman I loved handed me a spoon and a kiss and said, “Taste this.” I tasted. It was a sauce that needed salt. I added it.

On a Sunday, in our backyard garden, Pamela took my hands and said, “We are our own family now.” I looked at our house with its daisies and its lamps and its bills and its clean sink. I thought of a daisy cake that never got cut. I thought of an app that glowed for parents. I thought of a man in a navy suit murmuring apologies and then getting up every morning to go to a garage and earn the ability to look me in the eye.

“Yes,” I said. “We are.”

There is a photo from our first anniversary. We’re in the backyard, the daisies behind us, my mother’s hand visible in the corner of the frame because she held the phone too close. My father is in his chair off camera, shouting, “Smile bigger!” Chase’s hand is on my shoulder. Pamela is laughing. I am looking at the camera the way people look at a friend they trust.

On the back of the photo, my mother wrote in careful, shaky letters: My son is enough.

I keep the picture on my desk and a copy of a bank transfer confirmation in the drawer. When people ask about the moment at the party—the scrape of the chair, the still air after the sentence, the weight of a phone in my hand—I tell them this: there are two kinds of loud. There’s the loud that gets applause and there’s the loud that builds a life. The first is easy. The second is work.

A while ago, Aunt Linda asked how I forgave. I told her I hadn’t done it all at once. I told her I forgave in the same way I learned to code: one line at a time, failing, trying again, watching the logic flow where before there were only bugs.

Some days it still catches me, the memory of my mother’s face when she said, “You should learn from your brother,” as if love were a contest measured in applause and rent. On those days, I put Pamela’s cookies in the oven and call my mother and tell her about a bug fix that took three hours but finally worked. She doesn’t understand the code. She understands the word finally. She says, “I am proud,” and then tells me she took a photo of the daisies.

Sometimes Chase and I sit on the porch in Beckley and don’t talk about what happened because the silence says it better. He tells me an alternator is beautiful because it does its job without needing to be seen. I tell him a compiler is beautiful for the same reason. We laugh because we are finally speaking the same language: usefulness.

If there is a moral here, it is not revenge is sweet or good sons win. It is simpler and much harder: Transparency is love. Love that refuses to be confused with secrecy. Love that puts receipts on the table, metaphoric and literal. Love that refuses to live in a shadow—its own or anyone else’s.

On my mother’s seventy-second birthday, we cut the cake first. We ate it on paper plates. We took photos of frosting. My mother hugged me and whispered, “I still say I’m sorry. I still mean it.” I hugged her back and said, “I know. I forgive you. I am okay.”

Later, as we were leaving, Aunt Linda pulled me aside. “You’ll never be as good as your brother,” she said with a smile that had lost its sting, “because Chase isn’t you.” She winked. “You’re Alvin. Finally.”

I laughed. It felt like air.

Before we drove back to Austin, Pamela and I stopped at the daisies. My mother cut three and tucked them into a jar with tap water. “For your kitchen,” she said. “So you remember to add salt.”

On the highway, Pamela leaned her head on my shoulder and said, “What you said that night, at the party—‘Then ask him to pay’—it wasn’t just about money.”

“No,” I said. “It was about value.”

She kissed my cheek. The LED lamp, packed in a box in the back seat because my mother said it belonged in my house now, clicked softly against another box when we hit a bump. It still worked. Some circuits do. Some don’t. You replace the resistor and try again. You send money for parents and then you send love without it needing to be mistaken for cash. You stand up at your mother’s table and set a boundary and then you spend the next year building a life that doesn’t need a single person’s permission to be true.

In Beckley, the daisies bloomed until first frost. In Austin, ours kept going a little longer. In both places, when the light hit them at a certain angle, they looked like tiny suns—stubborn, shining, enough.

END!

News

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left. CH2

My Mom Announced In Front Of 52 People That I Never Helped Them — Then I Left Part One In…

At Dinner, My Sister Called Me A ‘POOR TRASH WORKER’ — Then A Guest Asked, ‘WHAT’S THE OWNER DOING?’ CH2

At Dinner, My Sister Called Me A “POOR TRASH WORKER” — Then A Guest Asked, “WHAT’S THE OWNER DOING?” …

I found out my husband had a mistress in a rather unexpected way my shampoo was running out way too fast! CH2

I found out my husband had a mistress in a rather unexpected way… my shampoo was running out way too…

My family texted “We need space from you. Please don’t reach out anymore. At all” CH2

My family texted “We need space from you. Please don’t reach out anymore. At all” my uncle packed them up….

During breakfast, my daughter said, “I have a surprise for you.” CH2

During breakfast, my daughter said, “I have a surprise for you.” She handed me an envelope. Inside was her husband’s…

My husband left me in the rain, 37 miles from home. He said i “needed a lesson I didn’t argue i just watched him drive away. CH2

My husband left me in the rain, 37 miles from home. He said i “needed a lesson I didn’t argue…

End of content

No more pages to load