My Parents Said, “My Sister’s Wedding Day, It’s Better I Not Be There.” So, I Vanished…

Part One

The night my parents told me their greatest gift would be my disappearance, I didn’t cry. I didn’t beg. I didn’t even slam the door as hard as I could have—the way you do when you intend to be chased. I left as quietly as you set down a glass you know is going to break no matter how gently you place it.

I’m Megan Rose Parker, twenty-eight, born and raised in Wood Haven, Kansas, the sort of town with a wraparound-porch aesthetic and “Good morning, neighbor” reputation that makes everyone assume the inside of your life is as tidy as your hedge. Our hedge was immaculate. The inside of our life was not.

My mother, Patricia, grew up the prettiest girl in a town that adored pretty girls and learned early that speaking with certainty gets the same result as speaking with kindness, but faster. My father, Michael, was a numbers man—steady, good with spreadsheets, allergic to conflict unless it meant backing my mother. Together they ran a local accounting firm, respected by everyone who didn’t have to share a dinner table with them. They had two daughters: Jessica—the sun around which we orbited—and me, the satellite blamed when the tides misbehaved.

I was eight when I learned the script. I won an art contest at school; my mother skimmed the certificate, said, “Cute,” and pinned it to the side of the refrigerator with the magnet that said Kiss the Accountant. My sister came home with first in Math Olympiad and Mom rearranged the entire fridge like it was a gallery and she was curating it for the Louvre. Dad ruffled my hair—as if I had done it to be cute—and said, “Your sister’s a natural. Let it go, kiddo.”

By middle school, I had learned the economy of silence. Speak only when it doesn’t interrupt the Jessica Show. In the backyard, if we fought over the tire swing, Patricia always ruled for Jessica. “Stop being selfish,” she’d admonish, eyes on me. “Family harmony matters,” Dad would add, which always meant I was the one meant to be quiet. In high school, I learned to stop trying to be seen for the same reason you stop touching a hot stove: it hurts and no one believes you can’t handle it.

When Jessica left for a top business program, we threw a party that made our house smell like expensive hope. My parents drove her to campus, posted photos with captions that read like press releases: Proud parents of a future CEO. I stayed in Wood Haven. I enrolled in the local community college to save money, helped out at the firm to “pitch in.” Helping meant running errands for my mother and filing papers for my father while I still smelled like lecture hall.

After school, I found work at a small marketing agency. It wasn’t glamorous, but it was mine. I rented a one-bedroom three blocks away from the house I’d grown up in because leaving completely felt like betrayal and because my mother’s “dizzy spells”—mysterious, conveniently timed—were easier to ferry from when you kept your shoes on. “Family first,” Dad would remind me in his best patriarch voice when he called during my lunch to tell me to drive Patricia across town for a stress check. “Your mother is relying on you.” Jessica visited twice a year, stayed at a hotel, posted family photos that made it appear she cooked the casseroles I baked, and asked me to tag her in the ones where her hair looked best.

So when Jessica announced her wedding and asked—by which I mean she forwarded me a Google Doc with six tabs titled VENDORS, PHOTO, CATERER, SEATING, MUSIC, DECOR—if I would “help,” I said yes. It was reflex. A doomed sort of hope can be a reflex.

For months, I poured every spare dollar and hour into someone else’s perfect day. I negotiated with a caterer to get Jessica’s roasted chicken without garlic because Patricia “can’t abide garlic” and if garlic was present, it would overshadow the golden child in the birth narrative she wrote each day. I scoured antique shops and Etsy for glass orbs to turn into centerpieces, choosing peonies because I remembered Jessica saying once—while flipping through a magazine, not looking at me—those were the only flowers that didn’t give her a headache. I designed the place cards myself, embossing each name in a font that had more elegance than flourish, stayed up until two a.m. reprinting when I realized the ‘t’ in Mr. Poritzky’s name didn’t look sharp enough. I made the seating chart with an eye for landmines. Aunt Denise would not sit near Pastor Hal because of last summer’s wine incident. Mr. Schaefer couldn’t sit under the AC vent because he wore his integrity like a rash. And Patricia couldn’t sit next to anyone who might be tempted to outshine her.

“Don’t mess this up, Megan,” Dad said when I slid the final timeline across the table a week before the wedding. He didn’t look at it; he looked at me, which was worse. Mom’s feedback on the menu was, “Your sister would have picked something more elegant,” while Jessica’s contribution remained text-bubble approval stamps—Looks fine—sent between meetings where she learned to lead without looking back.

The day before the wedding, I loaded the last of the centerpieces into my car. Forty-eight glass orbs nested in tissue and stubbornness. One box remained on my kitchen table—the one with the extra ribbon, the backup tea lights, the special piece I’d bought Jessica without telling anyone. A sapphire necklace, vintage, small enough to be delicate and big enough to represent my savings for a conference I’d dreamed of attending. I carried the boxes into my parents’ living room and set them down, careful in the way you always are with something fragile in a room where people aren’t.

“Where’s the rest?” Patricia’s voice cut the air. I turned, realized the box with the tea lights and necklace was missing, felt the floor tilt.

“I left one at my place,” I started, already reaching for my keys. “I’ll grab it now—”

“You forgot?” She slapped her palm against the counter hard enough to make the spoon jump in the sugar jar. “You always screw things up.”

“This is Jessica’s wedding,” Dad added, ever the echo. “Not some school project.”

Jessica stood on the stairs with her fiancé, David—hair perfect, tie loose, virtue easy. She looked anywhere but at me. He looked at his phone. Susan, the photographer from my mother’s church, stood near the window, pretending to arrange flowers, absorbing it the way people do when they intend to sell the story later for likes.

And then my mother said the sort of thing people claim in retrospect they didn’t mean. “The greatest gift you could give would be to disappear from our family permanently.”

Dad nodded. “It’s time.”

Silence is a muscle you can develop—if you exercise it sixty thousand times between eight and twenty-eight, it’ll be strong enough to hold you up when humiliation knocks out the power in the room. I put the box on the floor and picked up my keys. “You’ll get your gift,” I said, and left.

That night, my friend Leila texted me a livestream link. You okay? I watched alone in my apartment, the glow from the phone bleaching my hands. Jessica, stunning in lace and a sky that looked like it cared about her; my mother, luminous with satisfaction; my father toasting the myth he’d written with the voice he used for clients; a room full of people drinking our story. My name was not said. It felt like an eraser rubbing a hole through paper.

Grief can be gasoline if you let it. It lit something not as wild as vengeance and not as tired as resignation. More like a pilot light that had waited twenty years to be allowed to burn.

By sunrise, I had a list:

Sell the apartment.

Resign.

Freeze the shared accounts before my mother could “borrow” from them for non-medical emergencies like “a new patio fountain.”

Find a lawyer who’d know how to protect what I had paid into under the generous heading “Family.”

Leave without giving my parents the show they craved.

I called a real estate agent notorious for speed over sentiment. She came with a smile that said, This isn’t what you’d get if you loved yourself more, and a contract that said, You will love yourself more in a week when you no longer live here. I signed. I called Karen, a lawyer I’d met at a networking event who’d handed me her card and said, “When you’re ready to stop bleeding for other people, call me.” I was ready. She listened to the whole thing—the wedding, the text, the decades before—and said, “Freezing joint accounts protects you and them. We’ll create a trust with a third-party administrator for your mother’s documented medical expenses and household bills. Everything else will require proof. No more blank checks with your name on them.”

Steven, a financial attorney with a pen like a metronome, set up the trust. By noon the next day those accounts—family savings, the ones I’d fed—were under lock and key. I called my boss, used the phrase “personal reasons,” and swallowed the way his voice softened—you’ve given us nine years. I wanted to leave him better than I’d found him. I sent my resignation in writing and closed my work laptop the way you close a door on a room you learned to breathe in.

What I took fit into the back of my car: three dresses I loved, jeans that didn’t hurt my feelings, a pair of sneakers that made my legs feel like a possibility, my college journal, the necklace from my art teacher who’d told me to make beauty even if no one paid for it. I left the couch I’d had delivered up three flights of stairs by two men who called me sweetheart and then Lady, depending on how much they wanted a tip. I left the dishes Dad had said weren’t my taste and had been, of course, exactly my taste.

I chose Tidewater, South Carolina, because the name made my lungs ache in a good way and because a map app told me it was far enough from Wood Haven to sound like a soft word. I found a furnished cottage on stilts, bleaching white and peeling, with a porch that looked out over a marsh that looked like it had something to say. Month-to-month, no questions asked. I signed the lease as “Elaine”—my middle name—and asked the landlord, “Do you care who I was a week ago?” He said, “Do you pay on time?” I said, “I always have.”

I set up a P.O. box and an LLC: Elaine Rose Creative. I put up a simple site with clean lines and a promise: I’ll make your brand look like it talks to people not to itself. I built client pipelines the way I once built centerpiece spreadsheets. In the evenings, I ran along the marsh until the voices in my head—my mother’s correction, my father’s disappointment—dropped behind like cars that had missed the exit. In the mornings, I took my coffee at Saltwater Brew, where Maria, the owner, poured it into a chipped mug as if we had been friends in another life and were catching up slowly. “New face,” she said the first day, as if Tidewater were a cat and we were fresh fish left on the back step. “This town is good at holding people until they find their feet.”

Three weeks in, my old phone—a landline to the life I’d ripped out of—vibrated itself out of the drawer. A voicemail from my mother: “Where are you? This isn’t how family behaves.” A text from my father: “Your mother is in the hospital. You need to come home.” The rope. The hook. The bait. I didn’t bite. I emailed Dr. Evans, Patricia’s physician, with a subject line more calm than my hands: Patient status. She wrote back what I already knew: not life-threatening, likely panic-induced, a need for not more attention but different attention.

Then something uglier. A post in a Wood Haven community group: Our daughter stole from us and abandoned us in our time of need. Photos of my mother’s hand with an IV, dramatic in the way theatre children make their pain legible. Comments from neighbors who’d eaten our casseroles and bought our “Proud Parent” sign: how could she, after everything Patricia and Michael had done? Dad chimed in with “We trusted Megan and she betrayed us.” Jessica, privately, emailed: I’m sorry. I didn’t realize it was this bad for you. Please call. We can fix this. The unread pile on my phone felt like a coffin lid.

I forwarded the screenshots to Steven. “Prepare a statement,” I said, “but not for Facebook. For the file marked ‘If this goes to court.’” He reminded me the trust had paid every legitimate expense: prescriptions, utilities, the portion of the mortgage my mother always claimed was “nothing” until it came due. He sent me a neat ledger and something that felt like permission: “You don’t have to defend yourself to a town that likes its villains obvious.”

When guilt slunk back into the house like a stray cat, Maria swatted it kindly. “Mine did the same,” she said, refilling my mug. “They put their weight on me to keep themselves upright. You put your weight down for you. Different kind of balancing act.”

I painted in the afternoons—not landscapes or portraits but little squares of color that felt like feelings I had not been allowed to use. I sat on my porch and wrote myself letters I would never mail. I turned off the alerts on my old phone and let my new one learn only my Tidewater life. I went to a book club where no one knew my sister was a star and no one asked who my parents were. When I introduced myself as Elaine, no one corrected me. In a town that had watched too many people run to the water to find themselves, no one needed to know the name of the person I had been told to be.

The old life did not surrender. It tried one more time. A voicemail from Patricia: “We need to talk.” A text from Jessica: I miss you. “Missing me,” I thought, sitting on the porch above the marsh as the light bruised from gold to mallow, “was a job none of you took when I was ten.” I wrote Jessica a letter I did not send: I believe you miss the version of me who absorbed things you should have held.

By the time the first southern storm blew in, I learned I could sleep through lightning. The storm hissed against my windows and the marsh put its green shoulder against the house and held it up.

Part Two

When you leave, you expect silence. Sometimes you get the weather.

On a Friday morning that would have been the one-month anniversary of Jessica’s wedding if I had been counting, a white envelope arrived at my P.O. box. No return address. Inside: a copy of a letter on Foster Accounting letterhead—my father’s signature slashed at the bottom like a wound. NOTICE OF OUTSTANDING BALANCE. The letter accused me of “misappropriating family funds” and threatened legal action if I didn’t return what I had “taken.”

I laughed, out loud, in a federal building. People looked. “Sorry,” I said to the woman from the Tidewater Garden Club, who wore a hat large enough to shelter a playground. “He’s always had a sense of humor.”

I forwarded it to Steven, who called me on his lunch break. “It’s posturing,” he said. “Legally absurd. You contributed to those funds. The trust shows every expenditure. If they sue, we counterclaim—and we ask for documentation they cannot provide.” His voice softened. “You’re okay?”

“Better than okay,” I said, and surprised myself by meaning it.

I landed a contract with a local boutique hotel—six rooms, a lobby that smelled like oranges and old books, a front desk clerk named Jamie who loved to tell me that hospitality was just “nice people doing their chores.” I rebuilt their website, cleaned up their SEO, shot a morning where a couple ate croissants in bed and made everyone on the internet want to be them. I taught the owner how to open his calendar app without using his thumb like a cudgel. When their bookings doubled, he sent me flowers and a note: You made us feel like the picture again. I taped the note to my fridge and stared at it the way you look at a new freckle: something small and lovely that will now be a part of you.

“Elaine!” Maria shouted one afternoon, leaning out the café door with a towel over her shoulder like an apron. “Meet my cousin, Luis. He needs a brand for his landscaping company. He pays cash and compliments.” Luis shook my hand and told me I had strong palms. It felt like a blessing.

I painted more. My squares of color grew into canvases slim as summers. Maria hung one above the coffee condiments and told customers, “It’s Elaine. She moved here to unlearn some noise.” I watched strangers tilt their heads in front of my work and felt something unclench.

It took exactly six weeks for the first apology that didn’t wear a mask to arrive, and it did not come from Patricia or Michael. Jessica sent an email with no subject line. I was cowardly, it said in the first sentence. I let them treat you like an understudy in your own life. I stood on stage and called it “family.” I didn’t realize how bad it was because I was the beneficiary of the bad. I am sorry. I can’t un-stand on that stage, but I can step down now.

It took me a day to respond. Thank you, I wrote. An apology does not change my address. I love you. I am okay. I need time.

She wrote back: I’ll wait. Also… David and I are done. The wedding was a production. The marriage is a plot hole. I’m moving out. Don’t worry—I won’t move to Tidewater. But will you FaceTime me once a week? We can be sisters without the chorus.

We started on Sundays. We spoke in a way we never had—like women without an audience, like children learning a second language. “What did you eat today?” “What did you draw?” “I found a therapist.” “I walked five miles and didn’t think about them until mile four.” We learned how to talk without comparing sorrows.

The next family blast arrived courtesy of Wood Haven’s latest gossip journalist, a man who had failed upward through enough journalism classes to know which rocks to turn over. He wrote an “exposé” using my parents’ version of events and three photos: Jessica throwing a bouquet, my mother dabbing the corner of her eye like it was a performance piece, me in my navy dress holding a box of centerpieces. He wrote “abandoned” the way men write “hysterical”—to fill a place where they don’t understand. His piece pinged around my old life like a marble in a glass bowl. Strangers shared it; people who had known me since I cried over scraped knees commented: We always wondered about Megan. So sensitive. There is a special kind of light that goes out when people who knew your first laugh assume the worst of you.

The morning it went viral locally, I put on sneakers and ran until my lungs burned. When I couldn’t run anymore, I walked into Maria’s café and she slid a paper bag across the counter like drugs in an old movie. “Blueberry muffins,” she said. “On the house. Also, on the community board.” I turned. She had pinned a sign above a flier for a dog-washing fundraiser: We believe women. We believe in starting over. We do not read Wood Haven Watchdog.

“Maria.” I choked on a blueberry. “I love you.”

“I know.” She refilled my coffee. “So does most of Tidewater. That’s the thing about leaving. Eventually, somewhere will be glad you did.”

Somewhere along the way, my days stopped feeling like days after disaster and started feeling like days. I stopped waking up assuming a crisis needed me to carry it. I worked, I wrote, I ran, I painted. I fixed a leaky faucet with a YouTube video and three phone calls to a man named Hank who said “sweetheart” but meant “neighbor” not “inferior.” I put up a wind chime that sounded like grace.

And because this is not a fairytale, a storm I didn’t order showed up on my marsh.

Patricia filed for emergency access to the trust. Her petition, printed on legal paper with my father’s signature two inches lower like always, claimed she needed $25,000 to “repair wedding-related damages and cover unanticipated medical expenses.” Steven texted me a photo of the filing with his commentary—“They’ve moved from Facebook to the courthouse”—and a plan. “We’ll respond with receipts. The trust has paid everything it’s obligated to. We’ll offer to cover therapy.”

“Offer therapy?” I asked.

He laughed. “The court will deny the cash request. Offering therapy makes you look like the adult we already know you are.”

We filed: a ledger of prescriptions, utility bills, proof of mortgage payments, a notarized letter from Dr. Evans outlining my mother’s diagnosis: panic disorder exacerbated by stressors, not a cardiac event. The judge denied Patricia’s request in a paragraph that made all the right noises. Then, in a line I might have tattooed on my ankle if I were the sort of woman who put things on her body to remind her of what she already knew, she wrote, This court will not be used as leverage in family power struggles born of disappointment and pride.

The day after the denial, Jessica called me laughing—not cruel, giddy. “Mom tried to convince the judge her panic attack was my fault because I wore off-white to my rehearsal dinner,” she said, and the laughter turned into something wetter. “I’m sorry. That’s not funny. It’s just…she is unraveling without you there to knit her up.”

“She’ll learn,” I said, and then spared my sister the speech about women being taught to blame other women for men’s boredom. “Or she won’t.”

“How did you…stop needing them?” she asked, and the question shivered in the air like a frightened thing.

“I didn’t stop,” I said. “I put the need somewhere it couldn’t hurt me. Then I fed it other things. Sun. Work. Blueberries. Maria.”

Near the end of September, a storm bigger than family rolled in. Hurricane Ida grazed us with a temper tantrum. Tidewater turned pewter, the marsh swelled sour, the wind kinked itself around the power lines like a boy on a rope swing. I stockpiled batteries and bread, filled my tub with water, secured my porch furniture, then watched news coverage of towns that had taught me how to breathe drowning in an afternoon. When the worst of it passed, I dragged fallen branches to the side of the road, my hair stuck to my face, my arms green with sap. Maria came by with a shop-vac and a jug of iced tea and we sucked water from corners like thirst.

Two days after the storm, the sky couldn’t believe it had been angry. Maria texted: You outside? Look down the road. I stepped onto the porch as a dusty sedan pulled up behind my cottage. Jessica climbed out looking like a woman who had slept in her car and then sobbed in a restroom and then put the crying to bed and decided to live anyway. She wore jeans, a t-shirt that used to be mine, and shoes that were not appropriate for marsh. She looked small and true.

“Hi,” she said, as if we had seen each other yesterday. “I brought cinnamon rolls from that place in town. The guy said you are a goddess.”

“He says that to the goat that chews weeds by his back door,” I said, because you cannot let emotions into the house unless they take off their shoes. “Come in.”

She inhaled my cottage, which smelled like paint and lemon and someone else’s dream. She looked at my canvas on the easel—a square of sky pretending not to be blue. She touched the mug by the sink like a relic. Then she sat, folded, at my table. We ate sugar and wept. We laughed and wiped our faces with paper towels because my cloth napkins were still in a box labeled “Fancies.”

“Do you know what it’s like,” she said into the second cinnamon roll, “to realize you’ve been speaking in someone else’s accent?”

“Yes,” I said.

“I thought if I stood very still and shone very brightly, I could keep them off you,” she said. “But I think I kept them interested.”

“Yes,” I said again. “But you were a kid. It was never your job.”

We spent the rest of the day moving my couch to a better corner and writing a list for her: find a place to live that didn’t have her husband’s name on it; cancel the credit card her mother had “set up for emergencies”; call the therapist she had found and tell the truth; make chili for herself because nothing restores dignity like chopping onions and crying for reasons that make sense.

She left at dusk with leftovers and a peace lily Maria insisted would only die if you actively yelled at it. I stood on the porch and watched her taillights stitch themselves into the dark and thought: this is what limits make possible. You set a boundary and suddenly the field grows in a direction you haven’t been allowed to see.

It took Patricia another week to call. She did not begin with hello. “You’re manipulative,” she said, as if labeling me could undo what I had built. “You left and look what happened. Your sister and your father and I—”

“I didn’t hang up,” I said, and let her hear the gift. “You have sixty seconds. Do not waste them.”

She sputtered something about duty and motherhood and how I had broken her heart. I thought of my childhood and the way she had held my choices like a misprint. I thought of the trust paying her prescriptions. I thought of the judge refusing to give her cash to punish me. I thought of my marsh and how if you let it sit in salt long enough it becomes something you would die for.

“Time,” I said when a minute passed. “I hope you find a therapist who will tell you what is not my job to say.” I hung up. I did not call back. When she texted the next day—Family is everything—I wrote, Mine includes me now and blocked the number.

Winter came and Tidewater turned the color of oysters. My cottage got the sort of cold that requires socks and soup. I learned which window sticks and which one opens if you ask politely. I bought a scarf knit by a woman at the Saturday market and the first time I wrapped it around my neck I felt like I had put my name on my throat.

This is not the part where I tell you my parents apologized at Christmas and we took a photo in front of a tree so perfect it absolved us of everything. That is not our story. This is the part where I tell you that I sent a check to the Wood Haven shelter in my mother’s name and wrote, For women who leave anyway. This is the part where I tell you I put a gift card to the hardware store in an envelope and mailed it to my father with a note: Fix something. Not me. This is the part where I tell you that on Christmas morning I walked to the marsh and sat on the steps under a sky that refused to be blue for my benefit and I cried for the girl who stayed and for the woman who left.

In the spring, Maria insisted I hang three of my paintings in the café with tiny price tags tucked under the frames. “Name your worth,” she said in the bossy voice people use when they love you more than your fear. I wrote numbers that made my stomach hurt and then a couple from New York who had stopped in on their way to Charleston pulled out a credit card and said, “We’ll take them all.” The morning they left, the wall looked naked and proud.

Work found me. The boutique hotel referred me to a coastal inn, which referred me to a small chain of surf shops, which referred me to a woman who made dresses out of tablecloths. I built brands and websites and campaigns that felt like songs used to sell things humans actually wanted. My bank account recovered, then grew. I bought a new couch—a blue one big enough for story time. I hosted Tuesday “home nights” with a pot of something cheap and good: beans with ham, greens with vinegar, bread with butter that remembered being cream. People came. They brought their new names and their old clothes and their stories. We cried and pretended it was the onions.

In May, a letter arrived at my P.O. box on plain stationery. The handwriting was neat the way fear is neat. Megan, it read. I know you prefer boundaries to apologies, but I am trying to learn both. I have started therapy. It is hard in a way that has nothing to do with you. I cannot change how I mothered you, but I can stop mothering Jessica like she is a job. If I ever earn a phone call, I will not use it to ask for anything. I will use it to say, “How are you?” and I will mean it. —Patricia. I took the letter to Maria and we read it three times with our elbows touching on the café counter. “Do I call?” I asked. “No,” she said. “You plant it. You see if it grows.”

I folded the letter and slid it under a magnet on my fridge—the one that now read Kiss the Artist because a child with pigtails had made it at Tuesday night before painting her fingers Pepto-Bismol pink. I waited. A plant depends on weather and will.

By summer, Jessica had found an apartment with windows that taught you gratitude and a therapist who taught her how to say, “I feel” without apologizing. She drove down once a month. The first time she stayed at my cottage, she woke me at three a.m. because she heard the house “settling” and thought it was “an intruder in the walls.” We ate cereal at the counter in our pajamas and laughed until we scared the intruder away. The second time, we went to the beach and learned to read the tide like a mood. The third time, she brought a man named Brian who looked at her like she was a good story he didn’t need to edit. I made him peel onions and told him if he made her cry for the wrong reason, Tidewater would eat him. He said, “Fair,” and cried peeling onions and I thought, Maybe we are going to be fine.

In August, I sat at my porch and wrote a letter not to be sent—to the girl in the living room who held a box of centerpieces like it could save her life. You did not ruin anything, I wrote. They asked you to vanish because your presence made their story wobble. You left. You taught the story to walk without them. That is called freedom. I folded it and put it in my journal between a painting of three blue squares and a grocery list.

The night Wood Haven’s gossip reporter updated his piece with a breathless “EXCLUSIVE: TRUST DENIED,” he added a note that said, “Ms. Parker could not be reached for comment.” For once, that felt like a win.

On the anniversary of Jessica’s wedding—the day she spent in Tidewater eating cake from a box with friends who looked like a new sort of family—I turned off both phones and walked the marsh path. The grass bowed in the heat and the birds sat with their mouths open because they haven’t learned air-conditioning. I thought about family as something you can plant: you might get peonies, you might get weeds, you might get something no one warned you would bloom.

“I thought disappearing would be a loss,” I whispered to the water. “It was merely a way of being found.” The marsh did what marshes do: held me up.

A week later, I was on a call with a new client—a woman who made soap that smelled like the first bite of a yellow apple—when my doorbell rang. A courier stood on the porch holding a box with my mother’s handwriting on the label. Inside: folded fabric—the table runner I had embroidered with Jessica’s and David’s names last year and refused to deliver because I had nothing left to sew into. A note lay on top in that same careful hand. For Tuesday nights, if you want it. I am learning to sit quietly in rooms I do not control. —Mom.

I spread the runner on my table. It looked better with paint on it. I sent a photo to Jessica. She sent a heart and a “Wait until I tell our mother how many people will spill soup on it.” We laughed. I told Maria. She poured me coffee and joy.

One quiet Friday evening, as cicadas tuned their violins and Tidewater’s air hung like a patient curtain, I walked down to the dock. The sky did that thing it does where it forgets it is supposed to be blue and instead becomes all of the colors you’ve ever loved. I dipped my toes in the marsh and the marsh forgave me my shoes. I thought about the word “vanish” and the way magicians use it to trick you into thinking something is gone when really it has stayed and you have looked somewhere else.

I vanished from a story that could not hold me. I appeared in one that could. I left a family who loved the idea of me more than the work of me. I built a life that loves me back.

People still ask, in messages or at book club or over coffee at Saltwater Brew, “Do you miss them?” I say yes. Not because I want to go back, but because I am generous with the truth. Missing is not a summons. Sometimes it is a period at the end of a sentence you needed to write.

On Tuesdays, we host home night. The table runner with my sister’s wedding date in the corner stains beautifully. We place cards with names that people chose for themselves. We say grace the way Tidewater says it—by passing bread.

Sometimes, when the light is right and the water settles and the wind carries the sound of someone else’s laughter to my porch, I take out the sapphire necklace from my art teacher and wear it while I wash dishes. It looks good against dish soap. It looks like history and forgiveness. It looks like a girl standing in a living room with a box of centerpieces, letting go. It looks like a woman in a new town, drawing a map on a table runner while eight strangers write where they are from and what they want next.

If you’re reading this wondering whether you can leave the story you’re ruining yourself to fit, here is your permission slip signed in Tidewater ink: you can. You will not be a villain. You will be a woman on a porch at dusk with paint on her fingers and the kind of smile that makes new towns say your name as if they have known it forever.

END!

News

A POOR GIRL arrived WITHOUT SHOES at the INTERVIEW – MILLIONAIRE CEO CHOSE her among 25 CANDIDATES. ch2

A POOR GIRL Arrived WITHOUT SHOES at the INTERVIEW – MILLIONAIRE CEO CHOSE Her Among 25 CANDIDATES Part One…

POOR SECRETARY RENTS A BOYFRIEND FOR $500—HE’S A MILLIONAIRE CEO WHO CHANGES HER LIFE… ch2

POOR SECRETARY RENTS A BOYFRIEND FOR $500—HE’S A MILLIONAIRE CEO WHO CHANGES HER LIFE… Part One Elena Rivera typed…

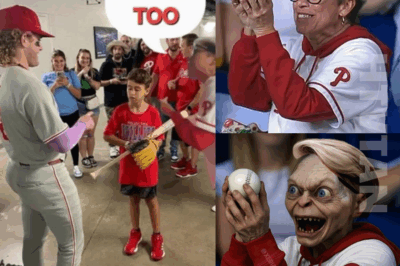

Phillies “Karen” Faces BRUTAL Fallout After Viral Ball Snatch

From stadium BOOS to online SHAME and RUMORS of job loss, the woman branded a “Karen Hall of Fame” member…

“You’ll Get the Ball Back, But Not Where You’d Like It to Be” — Whoopi Goldberg Slams ‘Phillies Karen’ After Viral Ballpark Drama

A Phillies fan branded “Phillies Karen” sparked national outrage after being caught on camera taking a home run ball from…

Phillies ‘Karen’ is facing the WORST backlash ever fans are NOT holding back…Should this be stopped?

Phillies “Karen” Faces Brutal Fallout: Viral Shame, Job Rumors, and a Stadium Exit From Outrage to Redemption: The Aftermath…

My Mother Told Me I Couldn’t Afford Dad’s Birthday Dinner — Then The Staff Greeted Me As The Owner.. ch2

My Mother Told Me I Couldn’t Afford Dad’s Birthday Dinner — Then The Staff Greeted Me As The Owner …

End of content

No more pages to load