My Parents Made Me Waiter At Sister’s Baby Shower and Laugh as I Served Drinks—But I Had the Last Laugh

Part One

Growing up, I always knew I was the extra—the spare chair dragged from the garage when the table was full, the face at the edge of the frame. While other kids had scrapbooks filled with baby pictures and milestones, my section in the family album started abruptly. No newborn photos swaddled in hospital blankets, no crumpled newborn wristband taped to the page. Just a blurry kindergarten shot with a crooked smile and a juice stain on my shirt.

My mother would laugh it off. “You were just a quiet baby. Not much to photograph.”

But my sister Claire—her first steps were framed on the mantle. Her baby teeth were saved in a velvet box with a little clasp that clicked shut like a secret. She had a cake for every birthday, even her half birthdays. She had a cake the year the dentist said she didn’t have any cavities. I, on the other hand, got a shrug and leftovers.

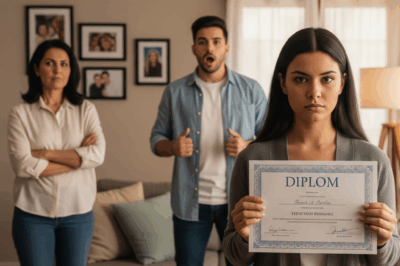

I learned early that my voice barely registered over Claire’s rehearsed piano solos and perfectly choreographed ballet routines. My report cards were filled with A’s; my teachers called me gifted; at home I was invisible. Once, I brought home a science fair trophy. My mother barely glanced at it before saying, “Just don’t leave it on the kitchen counter.” The next day it was gone. Tossed or donated. I’ll never know. But Claire’s third-place dance medal hung by the dining room light switch for years, catching the sun and clinking softly whenever someone brushed past.

Still, I loved them. Or I tried. You don’t stop loving people just because they forget to love you back. You wait. You hope. You think maybe if you just do more, they’ll notice.

So I planned Claire’s baby shower. Not because anyone asked me to—no one did—but because I thought maybe this time they’d see me. I made a spreadsheet in colors that matched the nursery palette Claire sent in a family group text (tiny white hearts, blush and sage). I paid for the decorations out of my own savings. I arranged the catering. I booked the venue with the last of my vacation pay. Every little pastel bow. Every IT’S A GIRL banner. I picked them all.

On my living-room floor, I spent nights folding paper flowers until the pads of my fingers went shiny. I tied ribbon around tiny bottles of soap shaped like baby feet. I designed and printed personalized thank-you cards on thick cardstock because Claire had once said she couldn’t stand cheap paper. I wrote a minute-by-minute schedule so the games wouldn’t run long and the food would stay hot. It was perfect. It was exhausting. But it was mine.

On the morning of the shower, the world was the color of expectation—white sky, pale sidewalks, that hush that happens on big days. I showed up early with my arms full of boxes and a heart full of a ridiculous hope I couldn’t seem to kill. My mother was already there, wearing a pearl necklace and sipping her second mimosa while directing the florist like a stage manager.

She scanned me the way she scanned receipts: quickly, to see if any line items were missing. She didn’t acknowledge the work I’d done. She didn’t ask about the ink stains on my fingers or the glue still clinging beneath my nails. She just looked me over and said, “Good. Now you can help serve.”

I laughed, thinking she was joking. “You want me to what?”

She tilted her head, puzzled at my confusion. “Well, someone has to hand out the cupcakes and refill the drinks, don’t they? It’s your sister’s day. Don’t make this about you.”

I looked around the hall I’d reserved, at the tables I’d draped with the soft linens I’d ironed until midnight, at the white balloons floating in careful clusters like half-moons. Every single person I had invited was smiling, posed around Claire while my dad narrated gift after gift with the showman cadence he kept for her milestones: “And this one is from Aunt Jean—look at the tiny socks! Claire always loved yellow…”

And me? I was in the back holding a tray of cupcakes I had paid for, listening to people laugh about how Claire had always been the favorite. The words landed like paper cuts, small and stupid and stinging. Then Claire turned to me mid-laugh and said with a wink, “You’re so good at blending in. You’d make a great caterer.”

The crowd laughed.

It didn’t hurt the way you might think—sharp, immediate. It was hollow, heavy, stretched across years. It was the weight of every time I had placed myself just to the left of center because I’d been taught center wasn’t mine. It was my mother’s voice calling, “Claaaire, come here, baby,” and my father’s, “Pumpkin, show everyone your dance,” and then silence where my name should have been.

I excused myself quietly, set the tray on a table, and stepped outside. No one followed. No one even noticed. The sky had decided to be kind and give the afternoon to birds; the side alley smelled like fresh-cut flowers and the faint sugar of frosting. I stood there with my hands braced on the cool brick and I chose. Not rage. Not a scene. A clean break, as clean as you can make it when the break runs through bone.

That night I didn’t cry. I pulled out the one thing I’d never shown anyone: my birth certificate, the document that proved I was just as much theirs as Claire was—something I had taken out sometimes when the house felt like a club I didn’t have the wristband for. When I had to remind myself I was not extra, I was fact. Across the top, a faint stamp read ADOPTED, the official label I had grown up hearing like a whisper at church, in parking lots, at the grocery store: “You know, she’s adopted.” It was always said with a little dip in tone, as if to say—so that explains it.

I held a thick red marker and did something I should have done years ago. I drew one straight, violent line through the word. Not across my name. Across theirs. It wasn’t a legal correction; it was mine. My declaration that belonging is not a favor bestowed by people who think they own you.

In the morning I put the document in an envelope—no note, no explanation—and mailed it to their address with a stamp that read LOVE in block letters. Let them decide what it meant.

I didn’t expect a response right away. But three days later my phone lit up. First Mom, then Dad—missed calls, then voicemails. One text from Claire: What the hell did you send them?

I didn’t reply. I was in the middle of something important, something I had postponed for far too long: reapplying to graduate school. I’d been deferring my dreams, making space for Claire’s spotlight, picking up extra shifts, babysitting her kids, catching the errands my parents tossed into the air. But now I was building something that didn’t require applause, something that was mine.

Three more days passed. Then a knock on my apartment door. I opened it to see my father standing in the hallway, looking smaller than I remembered—not older, exactly, just deflated, like someone had opened a valve you didn’t know existed. He held the copied birth certificate in one hand, the red slash still stark and angry.

“We need to talk,” he said.

I let him in, but I didn’t offer coffee. We sat at my tiny table—the one I’d bought secondhand and refinished in a color I called Optimism Blue.

He started fumbling through what he probably thought was an apology. “Your mother and I… we didn’t mean for it to come across that way. You know we love you. We always have. It’s just that Claire… she needed more.”

More attention. More praise. More money. More air. More everything.

I interrupted. “You made me the waiter at my sister’s baby shower. You let everyone laugh when she mocked me in front of a room full of strangers.”

“That was Claire just joking.”

“No,” I said, steady. “That was Claire doing what she knows she can do because you taught her she mattered more. Because you taught me I mattered less.”

He fell silent. His eyes wandered around my apartment, to the wall lined with books I’d bought one by one, to the Post-it constellation on the fridge that formed my application timeline, to the little shelf where I had set the small victories I had started collecting like armor: a “Thank you for speaking to our students” note from a local school; a ribbon from a community 5K where I’d run just to see if I could; a photo of me grinning, covered in paint, at a volunteer day.

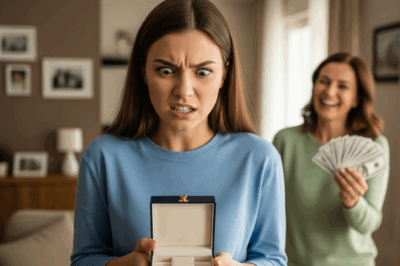

He stood to go. At the door he handed me a white envelope. “Your mother wanted you to have this.”

I opened it after he left. A check. Five figures. More than they had ever offered before. More than they had spent on Claire’s wedding, baby shower, and whatever else parents buy when the sun revolves around a person. A note was tucked inside in my mother’s careful, slanted script:

Use this for your future if it’s not too late to fix things. —Mom

I didn’t cash it. I didn’t even consider it. Because fixing things wasn’t about money. It was about the fact that for years the currency had been my silence.

The world didn’t change overnight. There was still rent to pay and a program essay to revise and a morning where I was late to work because the bus stopped for a funeral procession and an afternoon where I cried at a stoplight because I heard Claire’s laugh in the crosswalk. But little by little, a new muscle formed—the one that powers your own life.

I got into a program in nonprofit management. I took classes at night while working days at a community center. I spent weekends helping kids build papier-mâché landscapes and write poems about their neighborhoods and design costumes out of newspaper and glue sticks. I discovered that the bright, messy noise of other people making art could drown out the echo of a childhood full of whispers. I discovered that when a nine-year-old calls you “Miss J” and asks if you’re coming back next week, a hole you’d stopped noticing inside you starts to close.

By the time Claire’s baby had teeth, I had a degree, a job offer to run a small after-school arts program, and a question I could finally answer: Who do you become when no one is clapping? You become the person who doesn’t need the clapping. You clap for other people instead, and it feels like breathing.

Part Two

A few weeks after my diploma arrived in a stiff cardboard folder, the invitations went out for a celebration. Not the official ceremony—that had passed months ago in a gym where the sound system squealed and the cider was too sweet—but something better: a gathering for the people who had helped me build a life from scratch. The kids from my program. The volunteers. Three professors who’d stayed late to workshop my big grant application. Christa, who had given me my first admin job when I needed a purpose more than a paycheck.

For the venue, I booked the same hall I’d rented for Claire’s baby shower.

It was not pettiness. It was reclamation. I wanted to lace the room with a new memory so strong that it would dislodge the old one and take its place. I saved up, but I didn’t pay alone; this time, when people said, “Let me help,” I said, “Yes.” My team dragged strings of lights up ladders while singing off-key. The teenagers from our graffiti poetry project painted a giant cardboard backdrop that read MAKE YOUR OWN CENTER in colors so bright you could taste them. The parent committee ordered trays of food and made labels—Vegetarian, Contains Nuts, Extra Napkins Here—because they knew the way a small sign can make a person feel considered.

The night swelled toward joy the way a good song swells at the bridge. Someone’s aunt brought a trumpet. A shy kid who had barely spoken above a whisper in September got up and read a poem that used the word astronaut in three different ways. We laughed until we had to hold the table edges. We cried the kind of tears that leave your face lighter.

I invited my parents. They did not come.

But Claire did.

She arrived late, because of course she did, in heels that clicked like judgment and a dress worth more than my monthly rent. Her perfume announced her a beat before she reached the door. I braced myself for the usual performance—smirk, kiss for the air, a compliment that wasn’t.

Instead, when our eyes met, she gave me something I hadn’t seen in years: a look that didn’t know what to do with itself. The closest word I have is discomfort, but that’s not quite it. It was more like recognition passing through shame to land, carefully, on respect. She waited until no one else could hear and said, low, “Mom and Dad are embarrassed.”

“Are they?” I said, as lightly as I could.

“They didn’t know how much you’d done. They didn’t know you’d become this.”

“They didn’t want to know,” I said. It wasn’t cruel. It was true. Her mouth pinched and then softened. She didn’t argue.

In the corner a boy named Junie was struggling to carry a tray of cupcakes to the drink station, so Claire—Claire—stepped over, took half the tray without a flourish, and followed him. She set the cupcakes down and, for the first time in our shared history, served other people. I watched, not with resentment but with clarity. This wasn’t the universe correcting itself. It was my sister choosing a different action inside the same world.

During a lull, Claire walked the perimeter with me. We touched the backdrop; we admired the teens’ lettering; we ate something triangular and delicious I couldn’t name. When we reached the spot where I had stood with a tray a year ago, she paused and said, “I was terrible to you.”

“Yes,” I said. Sometimes the most generous thing you can do is leave the truth bare.

“I don’t know how to… fix it,” she said.

“You don’t,” I said. “You start doing small right things and keep doing them until they cover the surface.”

She nodded. She took off her shoes and danced with the trumpet aunt. I looked at the clock and realized two hours had gone by without me thinking once about how I looked. There are moments you don’t recognize as miracles until later; that night, I caught one as it passed and held it like a sparkler.

The celebration ended with laughter, real applause, and a group photo. Someone’s kid insisted I stand in the center and handed me a paper crown. We took four shots—in one my eyes are closed, in one I’m crying, in one the trumpet aunt does a pose so dramatic it looks like theater, and in one everything lands: I’m in the middle, not because I demanded it, but because I belonged there. My face isn’t cropped. My name isn’t forgotten. My worth isn’t negotiated.

I went home that night feeling full in a way I had never been full before—full without guilt.

The next morning a message sat in my inbox from my mother. No greeting, no closing, just a single line:

You made your point.

I stared at it for a long time. Then I wrote back:

I didn’t make a point. I made a life. You just weren’t part of it.

No anger. No demands. Just a truth she couldn’t erase with a check.

Months passed. Claire texted sometimes—awkward at first. How do you write a thank-you note to a teacher who changed your life? Do toddlers always throw the spaghetti they love the most? I found a copy of that book you loved in high school. Do you want it?

Slowly she softened. Maybe seeing someone else break free gave her the courage to examine the golden pedestal she had been born standing on. Maybe not. I didn’t require her redemption to feel complete. But when it came in small acts—a loaned stroller to a teen mom in my program, a donation to the art supply fund without asking for a plaque—I took it and planted it in the row of things I water.

One afternoon I stopped by my parents’ house, not to stay, not to reconcile, just to pick up a few boxes they’d found in the attic. It felt clinical, like a donation drop-off in reverse. Childhood stuff, mostly dust and the echo of rooms. In the bottom of one box lay the old family portrait—the posed one with the blue backdrop and the matching sweaters. I had once been part of that photo, perched on the arm of a chair, my body angled in because the photographer said, “Squeeze in! Let’s see those smiles.”

The version in the frame didn’t include me. At some point years earlier, a newer print had replaced the older one. I had discovered the swap by accident, a month after it was made; when I asked about it, my mother said, “We just liked this one better.” This time, as I lifted the frame, a thin something slid out and landed against my shoe.

A second photo.

Not the edited family portrait. A candid I’d never seen: me, in paint-splattered jeans, surrounded by kids from my program in front of a mural that looked like a sunrise learning how to be a phoenix. Someone—one of the teens, judging from the angle—had snapped it on a day we’d stayed late to clean brushes and talk about things that should be talked about gently. I was laughing. My hair was out of my face. In the corner a kid had written MISS J IS COOL in chalk. The photo had been printed on cheap paper and annotated on the back in a familiar hand: Claire sent this. —Dad

It didn’t undo anything. It didn’t make something unbroken. It was just a piece of evidence that reality had shifted half a degree.

I didn’t hang the picture. I didn’t need to. I already had a better frame: the boundaries I had built and the room inside them. I slid the photo into a book on my shelf—Art as Shelter—and stood there for a second, touching the spine, the way people do when they say grace.

And then, because life recognizes a good theme when it writes one, an invitation came for another baby shower—this time for one of the volunteers at my program. I helped set the tables; I tied the ribbons; I laughed with the aunties; and when someone handed me a tray and said, “Would you mind—” I said, “Sure,” and walked through the room, offering cupcakes to people who looked like they needed something sweet. No one laughed at me. Someone said, “Thank you,” and someone else said, “You throw a great party.” The lights were soft. The music was better than it had to be. We wrapped the mother-to-be in crepe-paper sashes like armor. I drove home with the windows down.

At a red light, my phone buzzed. A text from Claire: You were great tonight.

I smiled, set the phone face down, and waited for green.

The next morning a white envelope arrived in my mail. For a second my stomach clenched—checks and apologies lived in envelopes like that. But inside was a card with a watercolor of lilacs and a note in my mother’s handwriting:

We’re downsizing the hall closet. We found an old apron you used to wear when you helped your grandmother bake. Do you want it? —Mom

There are a thousand ways to say “I was wrong.” Some come in ten syllables: I’m sorry. I should have protected you. Some come in offers you can hold.

I told her yes.

The apron arrived wrapped in brown paper. It smelled faintly of flour and a memory I wanted to keep. I put it on and made a cake just because, and when the timer dinged, I didn’t wait to see if anyone clapped. I cut a slice, set it on a plate, and took a bite standing up, still in the apron, the room bright as a clean sheet, the air warm with sugar.

There was one last thing on my list, though I hadn’t known it was there until it was done.

I opened my laptop and created a folder called The Photo I Don’t Need. Into it I dragged a copy of the family portrait, then created a second document—a letter to myself, date-stamped and small. It read:

You are not the waiter.

You are not the extra chair.

You are the table.

I closed the laptop and went to work.

These days, when I pass the banquet hall on my way to the bus, I glance through the open doors if they’re setting up for an event. There is always someone with a tray, someone forgotten, someone glowing around the edges with a light even they can’t see yet. I find myself wanting to tell them what I learned the hard way: that it isn’t about the tray. It’s about whose hands your life is in.

Mine are steady now.

So yes—my parents made me a waiter at my sister’s baby shower and laughed as I served drinks. My last laugh wasn’t loud. It didn’t require an audience. It sounded like a key turning in a lock from the inside. It tasted like a slice of cake you cut for yourself and eat before anyone else arrives, because you can. It felt like standing where you used to fold yourself small and realizing, finally, you fit.

I didn’t make a point. I made a life. And when I set out the cups and fill them now, it’s because I choose to—at a table I built, in a room I own, for people who know how to pass the plate back to the person who brought it.

The photo at the bottom of the box can keep its dusty frame. I don’t need a place in their picture anymore.

I am busy living in mine.

News

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”— So I Chose Revenge. CH2

At My Mom’s Funeral, My Dad Slapped Me and Screamed, “She Died Because of You!”—So I Chose Revenge Part 1…

My Dad Told My Son, “If You Want to Eat, Go Find a Dumpster.” Mom Laughed. So I Threw Out Everything. CH2

My Dad Told My Son, “If You Want to Eat, Go Find a Dumpster.” Mom Laughed. So I Threw Out…

Mom Told Me, ‘You’ll Never Be As Good as Your Brother.’ So I Proved Her Wrong in the Best Way. CH2

Mom Told Me, “You’ll Never Be As Good as Your Brother.” So I Proved Her Wrong in the Best Way….

Mom Sold My Priceless Heirloom, Laughing, You’ll Thank Me Later! I Made Sure She’d Regret It Forever. CH2

Mom Sold My Priceless Heirloom, Laughing, You’ll Thank Me Later! I Made Sure She’d Regret It Forever Part One The…

My Parents Told My 7-Year-Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off. CH2

My Parents Told My 7‑Year‑Old She Was “Too Ugly” for the Family Photo — So I Cut Them Off Part…

Man Wouldn’t Let An Officer Sit In Coach, Then She Slips Him A Note. You Won’t Believe What’s Inside. CH2

Man Wouldn’t Let An Officer Sit In Coach, Then She Slips Him A Note. You Won’t Believe What’s Inside Part…

End of content

No more pages to load