My parents left me at a train station as a joke. Let’s see if she can find her way home. They laughed. I never went back. 20 years later, they finally found me.

Part One

This morning, 29 missed calls.

You know those moments when your past just crashes into your present violently without warning? That’s exactly what happened to me this morning. My phone lit up, a blinding beacon of dread. Twenty-nine missed calls from an unknown number.

And just like that, I was twelve years old again, standing alone at Union Station, watching my parents’ car drive away, their laughter echoing in my ears. “Let’s see how she finds her way home,” my mother had shouted, her voice a cruel whip. That day changed everything.

It took years of therapy—of clawing my way back from the abyss—to build a new life far, far away from the people who abandoned me. I never went back, not once, until now. Because somehow, after all these years, they found me. Before I tell you how that happened and how I finally rebuilt my life, let me take you back.

Growing up in Ridge View, Pennsylvania, felt like living in two different worlds. To everyone else, we were the picture-perfect family—Frank and Karen Taylor, successful small business owners with their two kids, Ethan and me, Jennifer, back then. But behind closed doors, our home was an unpredictable minefield.

My dad, Frank, owned the biggest hardware store in town. He was the pillar of the community, known for his booming laugh and those generous donations to local causes. My mom, Karen, ran a little bakery, famous for her County Fair blue-ribbon apple pies. To outsiders, they were the ideal American couple.

But the Frank and Karen I knew were entirely different people. Dad’s friendly demeanor vanished the moment he stepped through our front door. His drinking started around dinner and escalated throughout the evening. A bad day at the store meant walking on eggshells at home, every single night. And Mom? Instead of protecting us, she became his most loyal enabler, always making excuses. “Your father worked so hard for this family,” she’d say. Or, “He just needs to blow off some steam.”

Their parenting philosophy revolved around what they called tough love, which, looking back, was just cruelty disguised as discipline. It included these “teaching moments” that most people would recognize as pure emotional abuse. I was seven when they left me at a grocery store for over an hour because I’d asked for candy. “Maybe now you’ll learn not to be so greedy,” Mom had said when they finally came back, finding me sobbing by the customer service desk. The manager had been about to call the police.

My older brother, Ethan, three years my senior, had it so differently. He was the golden child—the one who could do no wrong. Star quarterback, straight-A student, Dad’s fishing buddy. While I got lectured for a 97% on a math test—“what happened to the other three?”—Ethan was praised for an A+. I became the family scapegoat. If anything went wrong, it was somehow my fault. Dinner was cold? I must have distracted Mom. Dad had a bad day at work? Probably because he was up late “helping” me with homework. The psychological burden was crushing for a child.

My eleventh birthday particularly stands out. Mom had promised a small party with a few friends. I’d been buzzing with excitement all week, even helping her bake cupcakes the night before. The morning of my birthday, they told me we were going to the local amusement park instead. I was disappointed but tried so hard not to show it. They drove nearly an hour, pulled into the parking lot, handed me twenty dollars, and said, “Have fun. We’ll pick you up at five.” I spent my birthday alone, too scared to go on any rides, just sitting on a bench near the entrance, watching other families laugh together. They picked me up at seven, not five, finding me terrified and in tears. “Just teaching you to be independent,” Dad laughed. “Besides, we had to pick up your cake.” There was no cake at home. No presents either. When I started crying, they called me ungrateful.

These “jokes” and “lessons” happened regularly throughout my childhood. I developed coping mechanisms—staying quiet, trying to be invisible, spending time at friends’ houses whenever possible, and losing myself in art. Drawing became my escape. On paper, I could create worlds where adults were kind and children felt safe.

The day before the train station incident remains crystal clear. I’d received my report card and was so proud of my straight As—except for one A- in science. To most parents, this would be cause for celebration. To mine, it was unacceptable. “An A minus?” Dad bellowed, waving the report card. “What’s wrong with you? Are you getting lazy? Ethan never got A-s.” “I tried really hard,” I whispered. “Clearly not hard enough,” Mom added. “We’re not raising mediocre children.”

That night, I overheard them talking in the kitchen. “She needs to learn that life doesn’t hand you anything,” Dad said. “She’s too soft, too sensitive.” “Maybe she needs a real lesson,” Mom agreed. “Something she won’t forget.”

The next morning, they announced we were taking a family day trip to Chicago. Ethan couldn’t come because of football practice. It was just going to be the three of us—something that rarely happened. Despite the previous night’s tension, I felt a glimmer of hope. Maybe this was their way of apologizing. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

I woke up with a strange mix of apprehension and excitement. Dad seemed unusually cheerful at breakfast, making jokes, ruffling my hair. Mom packed sandwiches for the road, humming to herself. The change in atmosphere was so dramatic it made me uneasy rather than relieved. The drive from Ridge View to Chicago took just over three hours. Dad played his favorite classic rock while Mom quizzed me on state capitals. If I got one wrong, Dad made a clicking sound with his tongue and said things like, “Even a third grader would know that one, Jen.”

As we approached the outskirts of the city, Mom turned around to face me. “So, Jennifer,” she said with an odd smile, “think you’re pretty smart, do you? Despite that A minus.” “I guess,” I answered cautiously. “Book smart, maybe,” Dad interjected, eyes on the road. “But street smart? That’s different.” “Real life doesn’t grade on a curve,” Mom added cryptically.

We parked near Union Station around noon. The massive Beaux-Arts building was intimidating, swarming with travelers rushing in every direction. I’d never been to Chicago before, and the sheer scale of the city overwhelmed me. “Hungry?” Dad asked as we entered the Great Hall. I nodded, clinging to the hope this might turn into a normal family outing. “Good. Wait here by this pillar,” Mom instructed, pointing to one of the massive columns near the main entrance. “We’re going to move the car to a better spot and grab some food. We’ll be back in fifteen minutes.” “Can’t I come with you?” I asked, anxiety creeping in. “What, are you a baby?” Dad laughed. “It’s just fifteen minutes. You’re twelve years old, for God’s sake.” “But I don’t know Chicago,” I protested weakly. “Exactly,” Mom said, with a strange emphasis. “Stay right here. Don’t move.”

I watched them walk away, disappearing into the crowd. The station clock read 12:17 p.m. I stood awkwardly by the pillar, watching people stream past. Businessmen with briefcases, families with luggage, couples holding hands. Fifteen minutes passed, then twenty, then thirty. The anxiety that had been simmering boiled over into panic. Had they forgotten where they left me? Had something happened to them? At the one-hour mark, I was fighting back tears. I didn’t have a cell phone. They hadn’t left me any money for a pay phone. I had seven dollars in my pocket—my weekly allowance.

Then, through the large windows facing the street, I saw our blue Ford Taurus drive slowly past the station. My heart leaped. Maybe they’d gotten lost. I ran toward the exit, waving frantically. As the car passed, I saw both my parents inside. Dad was driving slowly; when he saw me at the window, he grinned and waved. Not a wave of recognition or relief, but a taunting gesture. Mom rolled down her window and shouted words that would forever change my life: “Let’s see how you find your way home.” Their laughter echoed as they accelerated away.

I stood frozen, unable to process what had just happened. They left me on purpose in a city three hours from home, alone.

Denial gave way to crushing reality. This wasn’t a fifteen-minute lesson. They weren’t parking around the corner, waiting to jump out and say, “Surprise! Did you learn your lesson?” They were actually driving back to Pennsylvania without me. Complete panic set in. I ran back inside the station, gasping for breath, tears streaming down my face. The vastness of Union Station became terrifying. Too many people, too much noise, too many exits and entrances. Where could I go? What could I do? I had no phone, no contacts in Chicago, not enough money for a ticket home, and no identification.

For two hours, I wandered the station in a daze, occasionally breaking down in sobs before pulling myself together. I was afraid to ask for help. My parents had always warned me about “stranger danger” and said police would take disobedient children away to terrible places.

Around 3:30 p.m., a station employee named Janet noticed me. She was an older woman with silver-streaked hair and kind eyes behind red-framed glasses. She’d seen me circling the same areas repeatedly, clearly distressed. “Honey, are you lost?” she asked, kneeling to my level. I shook my head automatically, trained to never admit trouble to strangers. “Where are your parents?” she persisted gently. “They… they went to move the car,” I lied, my voice cracking. “When was that?” Janet asked, concern deepening. I couldn’t maintain the facade any longer. Three hours of abandonment, fear, and confusion poured out in a flood of tears. “They left me,” I sobbed. “They drove away and said to find my way home—but home is in Pennsylvania.”

Janet’s face shifted from concern to alarm. She led me to a quieter area near the station’s administrative offices, got me a bottle of water, and asked me to explain everything. Through hiccuping sobs, I told her about my parents, the A-, and watching them drive away laughing.

“What’s your name, sweetheart?” she asked. “Jennifer Taylor,” I whispered. “And how old are you, Jennifer?” “Twelve.” Her face hardened momentarily before softening again. “I’m going to help you, Jennifer. What you’re describing is not okay. Not at all.”

Janet informed her supervisor, who called station security. A kind security officer named Marcus took over, asking me more questions about my parents, our address, and phone number. I could see the adults exchanging grim glances over my head. “We need to call the police,” Marcus finally said. “What your parents did is abandonment. It’s against the law.”

And that was how, at 4:45 p.m. on a Saturday, I found myself sitting in a small office at Union Station, watching Officer Teresa Ramirez file a report about my abandonment. My whole body felt numb. This couldn’t be real. Parents don’t just leave their children in strange cities. But mine had.

The fluorescent lights of the Chicago Police Department’s First District Station buzzed overhead as I sat wrapped in a borrowed blanket, though it wasn’t cold. Officer Ramirez had brought me there after taking my statement. She’d been kind but professional, documenting everything with a seriousness that made the reality sink deeper. “We’ve tried calling your home number twice,” she informed me, setting down a cup of hot chocolate. “No answer yet.” My stomach twisted. “Maybe they’re still driving back,” I suggested weakly. The drive to Ridge View would take over three hours. A small, desperate part of me still hoped this was just an extreme lesson—that they’d turn around halfway home once they felt I’d been scared enough. “Maybe,” Officer Ramirez replied, but her tone said otherwise.

“Jennifer?” A new voice. A woman in her forties with curly brown hair approached, carrying a file folder. “I’m Laura Donovan from the Department of Children and Family Services. I’d like to talk with you for a bit, if that’s okay.”

The next hour passed in a blur of gentle questions. Had my parents done anything like this before? Yes, but never this extreme. Did they ever hit me? No, not physically. Did I feel safe at home? I hesitated too long before answering, which was answer enough.

“What’s going to happen to me tonight?” I finally asked, my voice small. Laura explained that since they couldn’t reach my parents, I would be placed in emergency foster care until the situation could be sorted out. The words foster care sent a chill through me. I’d heard stories about foster homes—none of them good. “We have a wonderful emergency placement family,” Laura assured me, seeming to read my thoughts. “The Williams family has worked with us for years. They have a daughter about your age.”

By 9:00 p.m., I was sitting at the Williamses’ dining table, picking at a plate of spaghetti I couldn’t eat. Diane and Robert Williams were trying their best to make me comfortable, but nothing felt real. Their daughter, Alicia, showed me to the guest room, awkwardly lending me pajamas and a toothbrush. “Your parents will probably come get you tomorrow,” she said, trying to be helpful. I nodded, not believing it.

I didn’t sleep that night. I lay awake staring at the unfamiliar ceiling, replaying the image of my parents driving away laughing. What kind of parents did that? What had I done to deserve it?

The next morning, after a breakfast I barely touched, Laura Donovan returned. Her expression told me everything before she spoke. “We reached your parents late last night,” she said carefully. “Are they coming to get me?” I asked, already knowing the answer. “Not yet,” Laura replied. “They said they were teaching you a lesson about independence and problem-solving.” Hot tears sprang to my eyes. “By leaving me in a different state?” Laura continued, “They claimed they planned to call the station after a few hours to check on you, but things escalated when authorities became involved.” Translation: They hadn’t planned to call anyone. They’d expected me to panic, maybe cry, and then what? Magically find my way home with no money, no phone, and no ID.

“Your brother Ethan confirmed you were expected home yesterday evening,” Laura added. “He was surprised when his parents returned without you.” A fresh wave of betrayal. So Ethan hadn’t been in on it. Small comfort. “What happens now?” I asked. “We’ve arranged a meeting at our office tomorrow. Your parents will be there. A judge has been notified and there will be a hearing later this week to determine next steps.”

The next 36 hours passed in a strange limbo. The Williams family was kind, but I felt like a ghost. Diane tried conversation; Robert offered board games; Alicia invited me to watch TV. I went through the motions, numb.

The DCFS meeting was set for 2 p.m. Monday. I changed back into my original clothes, hastily washed and dried. Laura drove me to a downtown office, explaining what would happen. “You don’t have to speak to your parents if you don’t want to,” she assured me. “I’ll be with you.”

We entered a conference room with a long table. Already seated were two other adults Laura introduced as her supervisor and a family court liaison. Five minutes later the door opened. My parents walked in looking nothing like the confident, laughing people who had driven away from Union Station. Dad’s face was haggard. Mom’s eyes were red-rimmed. Behind them came a man in a suit— their attorney.

“Jennifer,” Mom said, stepping toward me. I flinched. “Please take your seats,” Laura’s supervisor instructed firmly.

What followed was the most surreal conversation of my young life. My parents, guided by counsel, presented their version: concern about my “lack of self-reliance.” The train station “exercise” had been planned as a “controlled life lesson.” They had circled back “after twenty minutes” to check on me from a distance, but “couldn’t find” me. They assumed I had figured out how to call home or get help, demonstrating the resourcefulness they wanted to encourage. They drove home expecting to find a message from me—perhaps from a police station or a helpful stranger’s phone—“showing I had risen to the challenge.” “We were teaching her independence,” Dad insisted. “Kids today are too coddled.”

“By abandoning your twelve-year-old daughter in a city three hours from home with no money, no phone, and no ID?” Laura’s supervisor asked, incredulous.

“She’s exaggerating how little money she had,” Mom said dismissively. “And there are phones everywhere. She could have called collect.”

I sat in stunned silence. They weren’t sorry. They truly believed they had done nothing wrong.

The meeting continued with discussions of child welfare laws, potential charges, and next steps. Through it all, my parents maintained their position: this was a parenting choice—perhaps extreme—but with good intentions.

When finally asked if I wanted to return home with them, I found my voice. “No,” I said firmly, surprising even myself. “I don’t want to go back.” The shock on their faces might have been satisfying under different circumstances. “Don’t be ridiculous,” Dad sputtered. “Of course you’re coming home.” “That’s not your decision right now, Mr. Taylor,” the liaison explained. “Given the circumstances, Jennifer will remain in temporary custody while the court evaluates the situation.”

As the meeting concluded, Mom tried once more to approach me. “Jennifer, honey, you’re overreacting. We were just trying to teach you—” “To abandon people who trust you,” I interrupted, tears streaming down my face. “That’s what I learned.”

I was escorted from the room, my parents’ protests fading behind me. In that moment, I knew I would never see our house in Ridge View as home again.

The next weeks blurred—court hearings, interviews, therapy. The emergency placement with the Williamses was extended. Though they were kind, their home never felt like more than a waiting room. A month after Union Station, I met Thomas and Sarah Miller.

They arrived at DCFS on a Tuesday afternoon, both early forties, warm smiles reaching their eyes. Thomas taught high school art; Sarah was a pediatric nurse. No biological children, but foster parents for over a decade. “We believe every child deserves safety, respect, and room to grow,” Sarah said. “No pressure to talk about anything until you’re ready,” Thomas added. “We just want you to know our home is open as long as you need.”

Something genuine about them cut through my practiced distance. When Grace, my new social worker, asked if I’d try a placement with the Millers, I nodded cautiously.

They lived in a modest two-story in Evanston, just north of Chicago. My room had pale yellow walls, a window seat overlooking a small backyard garden, and empty bookshelves waiting to be filled. “We want you to make it your own,” Sarah said. “Pictures, posters, books—whatever makes you comfortable.” “What are the rules?” I asked wearily, thinking of the ever-changing expectations at my parents’ house. Thomas and Sarah exchanged glances. “Basic respect and safety,” Thomas replied. “Let us know where you are, help with chores, do your best in school. We’ll figure out the details together.”

I waited for the catch, the hidden expectations. They never came. The contrast was disorienting. The first time I spilled a glass of juice at dinner, I froze in terror, waiting for the explosion. Instead, Sarah handed me a cloth. “No worries,” she said. “Accidents happen.”

Trust came slowly, painfully. I kept waiting for the Millers to reveal their “true selves,” to drop the act of kindness and show the cruelty I’d been trained to expect. But day after day, they remained consistent in their gentle support.

Meanwhile, the legal process continued. My parents attended mandatory parenting classes and counseling, making what Grace called minimal effort. They complained loudly that the state had overreacted to a “simple parenting choice.” Dr. Reynolds, my therapist, helped me understand in clinical terms: emotional abuse, neglect, abandonment. She diagnosed me with PTSD and anxiety, introduced coping mechanisms that actually helped. For the first time, I learned that my parents’ behavior wasn’t normal. And, more importantly, it wasn’t my fault. “Nothing you could have done would have justified what they did,” Dr. Reynolds emphasized until I began to believe it.

Three months into my stay, Ethan visited. Sixteen now, my brother seemed smaller somehow—less golden child, more just a teenager. We sat awkwardly in the Millers’ living room while Sarah busied herself in the kitchen, giving us privacy while remaining within earshot. “They miss you,” Ethan said finally, staring at his hands. “Do they?” I asked, skeptical. “In their way,” he admitted. “Dad’s drinking more. Mom’s always cleaning.” “Are they sorry?” He hesitated. “They’re sorry you’re gone. I don’t think they understand why what they did was wrong.” “And you?” I challenged. “Do you understand?” He looked up. “I knew they were harder on you. I should have said something. I’m sorry, Jen.” It wasn’t enough, but it was honest.

The court proceedings culminated six months after the train station. Based on evaluations, home studies, and my testimony, the judge determined my parents had demonstrated a pattern of emotional abuse culminating in severe neglect and endangerment. My parents were given a choice: complete an intensive two-year rehabilitation program with supervised visitation—or surrender their parental rights.

To everyone’s surprise but mine, they chose the latter. “We won’t be vilified for trying to raise a strong, independent daughter,” my father declared. “If the state thinks it can do better, let it try.” And just like that, with a stroke of a pen, Frank and Karen Taylor were no longer legally my parents.

Three months later, on my thirteenth birthday, Thomas and Sarah asked if I would like them to adopt me. By then, I had begun to believe in the permanence of their care, the consistency of their love. “Yes,” I answered without hesitation. The adoption was finalized shortly before my fifteenth birthday. As part of the process, I requested a legal name change from Jennifer Taylor to Megan Miller—a new name for my new life. “You’ll always be whoever you want to be in our home,” Sarah assured me. “We just feel lucky to be part of your journey.”

Art became my salvation. Thomas recognized my talent early and nurtured it with supplies, books, and guidance. The sketchbooks I filled became a visual diary of my healing—starting with dark, fragmented images that gradually gave way to color, form, and hope.

High school brought new challenges and opportunities. Making friends wasn’t easy—trust issues don’t disappear overnight—but I built connections with a small group of fellow art students who accepted my quiet nature and occasional anxiety without judgment. College loomed. With Thomas and Sarah’s encouragement, I set my sights on the School of the Art Institute of Chicago—ambitious, but not impossible. “Wherever you want to go, we’ll help you get there,” Thomas promised.

The acceptance letter arrived on a snowy March afternoon during senior year. Sarah cried tears of joy. Thomas insisted on framing the letter. For the first time, I let myself believe the future could be bright and of my own making.

Before leaving for college, I made a decision forming for years: I would completely cut ties with my birth family. No contact. No updates. “Are you sure?” Sarah asked gently. “You might feel differently someday.” “I’m sure,” I replied. “The Taylors are my past. You’re my family now.” And with that resolution, I stepped forward.

College opened a world I’d only dreamed of. The campus buzzed with creative energy. Professors spoke about art like it could change the world. Everywhere, the freedom to experiment and grow. I declared a major in graphic design—combining visual art with practical communication. Each successful project rebuilt the confidence my childhood had dismantled.

Thomas and Sarah supported me from afar—care packages during finals, steady encouragement, respect for my independence. The balance they struck showed me what healthy parent-child relationships could look like, even as I entered adulthood.

Sophomore year brought Audrey into my life—bold where I was careful. “You’re the most deliberate artist I’ve ever met,” she observed over coffee. “Every mark you make is chosen.” “Is that bad?” “Not bad,” she said. “Just interesting. Makes me wonder what happens when you let go.” Audrey’s friendship challenged me in the best ways—pushing me creatively, respecting my boundaries personally. When I finally shared snippets of my past, she listened without pity. “They really screwed up losing someone like you,” she said.

It was Audrey who convinced me to try dating junior year after avoiding anything beyond casual friendships. “You don’t have to trust everyone,” she reasoned. “Maybe try trusting someone.” Brian was a photography major with kind eyes and patient hands. Our first date—coffee in a tiny café—stretched into five hours. He talked about growing up in rural Wisconsin, his parents’ dairy farm, his three younger sisters. I shared carefully edited pieces of my past. “My birth parents weren’t good people,” I said vaguely. “I was adopted as a teenager.” “Family’s complicated,” he replied simply. “I’m more interested in you now than where you came from.”

Our relationship developed slowly. Brian never pushed for more intimacy—emotional or physical—than I was ready to give. The first time he reached for my hand and I flinched, he simply nodded and kept talking. The next time, I was ready.

Dr. Reynolds had prepared me for the challenges of adult relationships after childhood trauma. “Trust issues don’t just affect romance,” she explained. “They color every connection. The key is awareness—recognizing when your reactions stem from past wounds rather than present realities.” This awareness helped when Brian and I hit our first serious conflict eight months in. A miscommunication about plans left me waiting alone at a restaurant for over an hour. By the time he arrived, profusely apologetic about a dead phone battery, I was locked in a bathroom stall, hyperventilating. “You left me,” I accused later—the words carrying the weight of abandonment far beyond a delayed dinner. Brian listened as I finally told him what happened at the train station. When I finished, he didn’t offer platitudes. “I can’t promise I’ll never disappoint you,” he said. “But I can promise I’ll never deliberately hurt you. And I’ll always—always—come back.” It wasn’t everything, but it was honest. We grew stronger.

Graduation approached. Thanks to a professor’s recommendation, I secured an interview at Element Design, a midsize firm specializing in branding for nonprofits and sustainable businesses. “We like your portfolio,” the creative director said. “But more importantly, we like your approach. There’s thoughtfulness here that can’t be taught.” I started at Element two weeks later, renting a tiny studio twenty minutes from the office. The space was all mine—the first time I’d lived completely alone. I painted the walls soft blue, hung my own artwork alongside prints I loved, and bought plants that needed daily care—small exercises in nurturing life.

Work challenged me in unexpected ways. The technical aspects came naturally; collaborating with clients and defending creative choices pushed me far outside my comfort zone. My supervisor, Nadia, seemed to intuitively know when to push and when to support. “Your work speaks,” she told me after I stumbled through a presentation. “Trust it. The confidence will follow.” She was right. Each small success led to the next. Within two years, I was leading projects for major clients.

At twenty-seven, Brian proposed during a weekend visit to Sarah and Thomas’s. He’d asked their blessing first—not out of protocol, but because he recognized their centrality in my life. We married in a small ceremony the following spring—Audrey as maid of honor, Thomas walking me down the aisle. “You’ve built something beautiful,” Sarah whispered during our mother-daughter dance. “We built it together,” I said.

Around that time, my birth parents made their first attempt to contact me. A Facebook message from Karen appeared on an ordinary Tuesday: Jennifer, we’ve been thinking about you. Would love to reconnect. I stared at the message for hours before showing it to Brian, then Dr. Reynolds. With their support, I maintained the boundaries I’d established years ago. I blocked the account without responding, then did the same when similar messages appeared elsewhere. The intrusions disturbed me, but I refused to let them derail the life I’d built.

Instead, I channeled the complicated emotions into a new venture. In 2008, I left Element to start my own studio, focusing on branding for organizations supporting children and families in crisis. Miller Creative became my professional identity—a name representing not just my work, but the family who saved me. From a spare bedroom, the business grew steadily—referrals, a growing portfolio. Brian supported the leap completely; his career as a commercial photographer provided stability during the uncertain early months. We discussed children but decided to revisit the question after the business was established. The thought of parenthood still triggered complex fears—of reproducing patterns despite my best intentions. “You’re not them,” Dr. Reynolds reminded me. “The fact that you’re concerned shows how different you are.”

Our apartment gave way to a small house with space for home offices and a guest room. The day we moved in, Brian surprised me with a rescue dog—a gentle one-eyed mutt named Scout with his own history of abandonment. “Thought you two might understand each other,” Brian said as Scout cautiously explored. He was right. Scout and I bonded immediately, his unquestioning affection healing parts of me that still harbored doubt.

With each passing year, the life I’d built felt increasingly solid—business thriving, marriage deepening, my relationship with Thomas and Sarah evolving into the adult dynamic I never expected to experience. My chosen family expanded to include Brian’s parents and sisters, who welcomed me without judgment. I had created a stable, healthy existence despite, or perhaps because of, the trauma that shaped me. The memories remained, but their power diminished with each conscious choice to live differently than I was raised.

Until this morning, when my phone lit up with those 29 missed calls—and the carefully constructed walls between past and present began to crumble.

I stared at my phone in disbelief. Twenty-nine missed calls from an unknown Pennsylvania number. My finger hovered over voicemail, heart pounding. Scout sensed my distress, pressing his warm body against my legs. Morning sunlight streamed through the kitchen windows, illuminating the ordinary scene—coffee mug, half-eaten toast, laptop open to client emails—now transformed by this unexpected connection to my former life.

I pressed play, holding my breath. “Jennifer—or Megan? I guess it’s Megan now.” A male voice, older but instantly recognizable. “It’s your brother. Ethan. I know it’s been years and you probably don’t want to hear from any of us, but Dad had a heart attack last night. It’s bad. The doctors aren’t sure if he’ll make it. I thought you should know. My number is—”

I disconnected before the message finished, hands shaking so badly I dropped the phone. Scout whined, nudging my palm. “I’m okay,” I whispered—to him, to myself. I wasn’t okay.

Within minutes, other notifications: an email titled Your father—please read. A Facebook message request: Jennifer, it’s Mom. Please call. It’s urgent.

Twenty years of silence. And now this barrage.

The panic attack hit without warning—chest tightening, shallow breaths, walls closing in. Fumbling for my phone, I called Dr. Reynolds’s office, grateful when she agreed to see me within the hour. “Your reaction is completely normal,” she assured me as I sat clutching a tissue. “This is a significant trigger—connecting to your core trauma.” “I thought I made peace with cutting them off,” I admitted. “Did you?” she asked gently. “Or did you build a life around the absence of that piece?” The question hit hard.

“What do I do?” I asked. “That depends on what you want,” she replied. “There’s no right answer. You can maintain the boundaries you’ve established—that’s valid. Or you can engage on your own terms. If there’s something you need from this interaction—closure, answers, a chance to speak your truth—consider that.”

Back home, I called the two people who earned the right to advise me. Sarah answered on the second ring. The instant I heard her voice, I broke down again. “Oh, sweetheart,” she said when I finished. “Tell me what you need.” “Tell me what to do,” I pleaded. “You know we can’t do that,” she replied gently. “But whatever you decide, Thomas and I support you completely.”

Audrey came over within an hour, pouring wine despite the early hour. “Okay,” she said, pragmatic. “What’s the worst that happens if you respond?” “They could pull me back into their dysfunction. Make me feel responsible. Dismiss everything. Re-traumatize me.” “What’s the worst if you don’t?” I considered. “I might always wonder. Maybe regret not saying what I needed to.” “Then this isn’t about them,” Audrey said. “It’s about what you need.”

When Brian came home, he found me surrounded by research—printouts about heart attacks, treatment protocols, recovery rates. “I see you’ve been busy,” he said, kissing my head. “I need to understand what’s happening medically before deciding anything,” I explained. “If this is really life or death—or manipulation.” “It’s not terrible to think that,” he said. “It’s self-protection.”

By morning, I decided: I would not call or visit immediately, but I would text Ethan. This is Megan. I got your message. I need more information before deciding next steps. How serious is his condition? What do you and Mom expect from me? His reply came within minutes: Thank you for responding. Major heart attack. He’s stable but critical. Triple bypass scheduled tomorrow. Mom’s a mess. We don’t expect anything. Just thought you should know. Would understand completely if you want no part of this.

The sincerity surprised me. I need time to think, I wrote back. Will be in touch.

Over the next three days, I spoke with Dr. Reynolds again, did intense self-reflection, and made a decision. I would meet with Ethan—only Ethan—at a neutral location to get a clearer picture before considering any contact with my parents.

We met at a coffee shop halfway between us. Seeing my brother after twenty years was surreal. The teenager I remembered was now a middle-aged man with thinning hair and glasses, rumpled button-down and khakis. “Megan,” he said, standing awkwardly. “Thank you for coming.” I nodded, not ready for pleasantries. “Tell me about Dad,” I said. Ethan sighed, relieved to focus on facts. Triple bypass successful, complications, ICU. Doctors cautiously optimistic, but at sixty-eight with his history—“What history?” “High blood pressure, high cholesterol, still drinks too much,” he said. “Retired five years ago when his heart problems started. Sold the hardware store.” I absorbed it, trying to reconcile the larger-than-life figure from childhood with this failing man. “And Mom?” “Falling apart,” he said. “They’ve been married forty-five years. For better or worse, completely dependent on each other.”

“Are you close to them?” I asked. Ethan hesitated. “Yes and no. I live an hour away. See them monthly. Nancy—my wife—isn’t their biggest fan, so we keep some distance.” “Why?” “After you left, things changed. Or maybe I started seeing clearly. They never really took responsibility. There were a lot of stories they told—to themselves, to family, to everyone. After having my own kids, I couldn’t keep pretending.” “What did they tell people about me?” I asked, both dreading and needing to know. “At first, that you were staying with friends in Chicago for school opportunities. Later, that you’d become rebellious and cut contact despite their best efforts. Most people believed them. They’re good at presenting themselves as victims.” The familiar anger rose. “And you let them?” “Yes,” he admitted quietly. “For years. I was eighteen, heading to college. Easier to accept their version than confront reality. I’m not proud of that.”

“Why reach out now—just because Dad is sick?” “Partly,” Ethan said. “But also because my daughter—Emma—is twelve now. The age you were when it happened. The thought of anyone doing to her what they did to you—” He couldn’t finish.

We talked for nearly two hours. Ethan filled in the twenty-year gap—his life as an accountant, his wife, their two children. He answered questions about our parents with painful honesty—neither defending them nor exaggerating their faults. “Have they ever expressed genuine remorse?” I asked finally. “Not regret that I left. Actual understanding.” “In moments,” Ethan said. “Dad has said, when drinking, that he went too far. That he wishes things had been different. Mom struggles more with responsibility. But they’ve both asked about you over the years. They keep a photo of you—your school photo from before—on the mantle.” The image disturbed me—my younger self preserved in their home like a memorial while the person I’d become remained unknown.

“Would you consider visiting Dad?” he asked eventually. “You wouldn’t have to talk if he’s awake. I can make sure Mom isn’t there if you prefer.” I considered. “I need to think about it.” He nodded. “Whatever you decide is okay. You don’t owe us anything.”

That night, Brian supported my inclination to see my father while maintaining strict boundaries. “Remember,” he cautioned. “You’re not that powerless twelve-year-old anymore. You’re visiting on your terms. You can leave anytime.”

The next morning, I called Dr. Reynolds and asked if she’d accompany me to the hospital—not as my therapist, but as a support person who understood the complexity. She agreed. “This is an opportunity to engage with your past from a position of strength,” she observed. “But only if it’s what you truly want.” I thought about the scared girl at Union Station, the years of healing, the life I’d built, and the parents who had chosen to abandon me. Then I thought about the man in the hospital bed. “Yes,” I said finally. “I need to do this. Not for them. For me.”

The hospital corridor seemed endless as we walked toward the cardiac ICU. Each step required conscious effort, my body trying to protect me by refusing to move forward. The antiseptic smell, hushed voices, occasional urgent beeping—everything heightened my anxiety. “We can take a break,” Dr. Reynolds offered, noticing my shallow breathing. I shook my head. “If I stop, I might not start again.”

Ethan waited at the ICU entrance, relief visible when he saw us. “Thank you for coming,” he said quietly. “Dad’s awake but tired. Mom’s at the cafeteria. I scheduled this when she’d be away, as you requested.” “And she agreed to that?” I asked skeptically. “Not exactly,” he admitted. “I told her I needed time alone with Dad to discuss insurance matters.”

As we approached my father’s room, Ethan touched my arm lightly. “Just so you’re prepared—he looks different.” I nodded, bracing myself.

Nothing could have prepared me for the sight of Frank Taylor—so imposing in memory—now diminished in a hospital bed, surrounded by monitors, tubes, and wires. A nasal cannula delivering oxygen. His chest bandaged beneath the gown. His eyes were closed but fluttered open at the sound of footsteps. For a moment, there was no recognition. Then his eyes widened. “Jennifer,” he whispered, voice raspy. “It’s Megan now,” I corrected automatically. “Megan,” he repeated, testing the name. “You came?”

I remained near the doorway. “Yes.”

Silence stretched—twenty years compressed into a small room. “You look like your mother,” he finally said. “I look like Sarah Miller,” I replied. “My adoptive mother.” His face tightened, then relaxed into resignation. “Of course. I deserve that.”

“Why did you want to see me?” I asked directly. He seemed taken aback. “You’re my daughter.” “I was your daughter,” I corrected. “Until you decided a twelve-year-old needed to find her own way home from Chicago.” He flinched. “We made a mistake. A terrible—” “A mistake is forgetting to pick someone up,” I said, voice steady. “A mistake is being late. What you and Mom did was deliberate cruelty disguised as parenting.” Years of therapy had prepared me for this moment.

“You’re right,” Frank said quietly. “There’s no excuse. I’ve had a lot of time to think, especially since—” he gestured weakly at the equipment “—since this. When you’re facing the end, you see things differently.” “Are you dying?” I asked bluntly. “Not immediately, they tell me. But it was a warning shot.” A humorless smile. “Makes a man reflect on his regrets.” “And I’m a regret?” “What we did to you is my biggest regret,” he clarified. “Not you. Never you.”

The door rustled. Karen Taylor stood frozen in the entrance, coffee cup in hand. “Jennifer,” she breathed. “It’s Megan,” Ethan corrected quickly. I turned to face the woman who had given birth to me, then laughingly abandoned me. At sixty-five, she was still carefully put together—colored hair, makeup, tailored clothes despite the hospital setting. Only her eyes betrayed her age. She moved toward me as if to embrace me but stopped when I stepped back. Her hands fluttered, then dropped. “You’re so beautiful,” she said, eyes filling. “All grown up.” I remained silent. “I’ve thought about you every day,” she continued. “Wondered where you were, if you were happy. If you ever thought about us—” “Karen,” Frank warned weakly. “Give her space.” The irony was almost funny.

“I need air,” I announced, turning toward the door. Dr. Reynolds moved with me. “Please don’t leave,” Karen called. “Please, we’ve missed you so much.” I paused in the doorway, turned back to face them both. “You missed me? You abandoned me in a strange city when I was twelve. You drove away laughing while I watched. You surrendered your parental rights rather than admit you were wrong. And now, twenty years later, you want to talk about missing me?”

The words poured out—years of unexpressed anger finally finding voice. Karen flinched as if struck. “We were terrible parents,” she admitted, tears flowing. “We didn’t know how to love you properly.” “That’s not an excuse,” I replied. “Millions of people figure out how to parent without abandoning their children.” “You’re right,” Frank said from the bed. “There is no excuse. We failed you completely.”

The simple acknowledgment—devoid of justification—disarmed me for a moment. This was what I had needed to hear twenty years ago: not explanations, but accountability.

“I didn’t come here for apologies,” I said finally. “I came to see for myself that the people who had such power over me are just that—people. Flawed. Aging.” I took a breath. “I came to decide, with my own eyes, how much space you still take up in my life.”

Part Two

I didn’t leave the hospital that day. Not immediately. Dr. Reynolds and I moved to a quiet family lounge down the hall, where the walls were painted a soothing green that looked like it belonged to a different building. “How do you feel?” she asked, handing me a bottle of water. The question was so simple it almost made me laugh.

“Lighter,” I said after a while. “And heavier. Is that possible?” “It is,” she said. “You put some weight down and picked up another. That’s what truth can feel like.” We sat there with the hum of the vending machines as our only witness. When Ethan joined us, he kept a careful distance—respectful of the boundaries I hadn’t had to articulate.

“I can keep Mom away for as long as you want,” he offered, voice low. “Thank you,” I said. “I’m leaving soon. But I’ll come back tomorrow—for ten minutes. Not to talk. Just to see.” “I’ll make it happen,” he promised.

That night, back home, I sat on the floor with Scout’s head in my lap. Brian made tea and put it within reach. We didn’t talk much. He knew when not to. When I finally spoke, my voice surprised me with its steadiness. “I am going to write them a letter,” I said. “Both of them. With rules.”

The next morning, I did exactly that. I wrote two letters—one to Frank, one to Karen—and printed a third copy for myself because I wanted a record of the boundaries I was building. Each letter was three pages, clear and unadorned. If we were to have any contact, it would be on terms I chose.

Rules for Contact

I will not discuss the past unless I choose to. Any conversation about “lessons” or “parenting styles” ends contact.

No guilt. No rewriting. No “we did our best.” If you need to process, do it with a therapist, not with me.

My name is Megan Miller. Sarah and Thomas are my parents. If that fact is diminished, defended against, or mocked, contact ends.

No surprise visits. Communication by text only at first. If we progress to calls, they will be scheduled and time-boxed.

I reserve the right to stop at any time, without explanation.

At the bottom I wrote what I believed was the kindest truth: If you want to know me, you can—slowly. You will not know Jennifer again. She is safe where she belongs—in my past. I am Megan. If you cannot accept that, I wish you well.

When I returned to the hospital for my promised ten minutes, I handed the letters to Ethan. “Give them these when I leave,” I said. He nodded. “I’m proud of you,” he added, surprising us both. I stood for a moment in the doorway to my father’s room, watching him sleep. His face was slack with exhaustion, his chest rising and falling under the blanket. He looked like a man in a bed, nothing more. It was a relief.

“Goodbye,” I said, too softly for him to hear. Then I left.

Weeks recalibrated. I returned to client work, to emerging projects, to the quiet rituals that anchor a life: grocery lists, watering plants, answering emails, walking Scout. I told Sarah and Thomas about the letters. They read them and, as was their way, asked no additional questions. “They are clear,” Thomas said. “Clarity is a kindness.”

Two weeks after I sent them, a text arrived from an unfamiliar number.

Frank: I read your letter ten times. I accept your rules. No more excuses. No more “our best.” If you ever want to talk, I will be here when and if you decide. If I don’t hear from you again, I will still be grateful to have seen you. —Frank

It should have been simple to ignore. It wasn’t. Another week passed, then another. Then a second text.

Karen: I want to know Megan. I don’t know how to accept what we did and also move forward. If you ever want to tell me how, I will listen. If not, I will learn on my own. I will not show up at your door. I will not call. I will wait.

Waiting is not something I associate with my mother. The words landed like coins on a counter—heavy enough to notice, not nearly enough to pay the debt.

I didn’t respond. I did, however, call Ethan and ask how Frank was doing. “Recovering,” he said. “Stubborn. Scares the nurses by pulling at wires when he wakes up confused. But they say he’s improving.” He paused. “Mom started going to a support group. She won’t talk about it, but… it’s something.”

Part of me wanted to scoff, to chalk it up to another performance. Another part, the part that had spent years in therapy learning to hold two things at once, made room for the possibility that people can begin. Beginning isn’t the same as changing. But it’s adjacent.

Spring tilted into summer. I turned thirty-two. Audrey painted me a riot of a canvas with a tiny train station hidden in one corner. She didn’t point it out; she knew I would find it. Brian took me to a new restaurant and asked permission to invite Sarah and Thomas to a surprise dessert because he knows I like to brace. We ate cake and then split a second piece because we could.

Three months after Frank’s surgery, another text: Cardiac rehab is humbling. I am learning to walk differently. Maybe we all are. —F. I stared at it for a long time, then responded with the smallest, truest thing I could offer: I hope it helps.

Four words. It was the opening of a window, not the door. I felt the air move.

The first time I agreed to a phone call with Frank, I rehearsed it with Dr. Reynolds like a performance. We chose a twenty-minute timer and practiced how to exit if he pushed into places I didn’t want to go. I wrote a sentence on a sticky note and put it on my desk in front of me: You can stop.

When I called, he answered on the second ring and then didn’t speak for a full five seconds, which in phone time is a century. “Thank you for calling,” he said finally.

“How are you feeling?” I asked, the safe question. He talked about rehab. About the gruff physiotherapist who called him on his self-pity and the nurse who told him his liver numbers were happy he’d finally stopped drinking. He told me about downsizing, about driving less, about walking to the end of the block and back every morning like it was a mountain. He did not mention my childhood. He did not say “I did my best.” When the timer chirped, I said, “I need to go.” He said, “Thank you. That’s enough.” He didn’t ask for more.

We talked again two weeks later. Then a month after that. Sometimes we spoke about books—surprise; he’d started reading novels in the cardiac ward. Sometimes about Scout. Once, about the inside of Union Station—he asked if it still looked like a cathedral for trains. “It does,” I said. “Hums the same, too.” We did not speak about that day.

Karen texted occasionally—pictures of ordinary things: the rosebush she’d managed not to kill, a pie that burned, her attempt at yoga. It was unnerving, and also, somehow, honest. She was not telling me who she used to be. She was telling me who she might become.

And still, I kept the window small. When she asked if she could call, I said not yet. When she asked if she could send a letter, I said yes. It arrived in late August, five pages written in the looping script I remembered from school lunch notes that always included a P.S. about manners. This letter had none. It began with three words: I was wrong. It ended with a question I did not expect: What does an apology that is useful to you look like? I set it down and walked around the house once with Scout and let my heart decide if that moved anything inside me. It did.

I wrote back with bullet points, because sometimes clarity requires a list:

Name it: not “what happened,” but exactly what you did.

Don’t center yourself: no “I feel so bad.” I know you do. I feel worse.

Don’t ask me to absolve you: that’s a church’s job or a therapist’s or your own, not mine.

Say what you will do differently: with other people, with yourself, even if not with me.

Two weeks later, a second letter arrived. It was shorter. It did all four things. It did not heal me. But it put something down that had been clenched in my chest for two decades. I kept the letter. I did not call.

In late September, I got an email from a nonprofit in Chicago—an organization that ran mentoring programs for youth in the foster system. They wanted a rebrand: warmer, more honest; less “hand-out,” more “stand-with.” The work sounded like oxygen.

The kickoff meeting was scheduled at a co-working space near the West Loop. On the second day, I parked a few blocks away and—without planning to—walked an extra six blocks past Union Station. I hadn’t stood outside it since I was twelve. I could have turned away. I didn’t. I stood across the street and watched people flow in and out—hurrying, hugging, hauling. A woman with a toddler on her hip dropped a stuffed rabbit; a stranger picked it up and jogged after her. A man in a suit stopped to help an older woman with a cane navigate the curb. A teen in a hoodie held the door for a string of people as if he’d invented courtesy that morning.

I crossed the street and walked up the steps. The Great Hall was exactly as I remembered and not at all. My feet knew the direction to the pillar where I had stood. I put my hand on the cool stone and counted to twelve, for the girl I had been. Then I walked to the information desk.

“Can I help you?” the clerk asked. “Yes,” I said, smiling, and I pulled a notecard from my bag. On it, I had written a message. “Would you mind posting this on your board for a week?” He glanced at it, then at me, then nodded. He pinned it carefully between a lost scarf notice and a flyer for a jazz trio. My message was short:

Twenty years ago, I was left here at twelve. A woman with red glasses noticed me. A guard named Marcus called the police. You saved me. If you were either of you, thank you. —M.M.

I didn’t expect it to reach them. It wasn’t for them, if I’m honest. It was for me. To place gratitude where terror had lived.

Outside, my phone buzzed. A text from Frank: My rehab PT says I can try a train to Philly next month. The way she said “try” made me laugh. I think of you when I laugh now. I took a photo of the building—not the pillar, not the door, just the long sweep of glass and stone—and sent it back with two words: Me, too.

The first time I agreed to meet Frank in person outside the hospital, it was at a park halfway between our cities. Public. Open. Sunlight available in case we needed it. He arrived early and sat on a bench facing a lake where geese muttered like old friends. He stood when he saw me, then sat when I stayed standing. “Thank you,” he said. He had brought no gifts.

We talked about birds for ten minutes. Then about nothing for five. Then, finally, he said, “I brought something. It’s not a gift.” He pulled a page from his jacket pocket, folded in half. “It’s a list,” he said, and my eyebrows rose because lists were my language.

He handed it to me. The title read: Things I Will Not Say To Megan. Under it, a numbered list:

-

I did my best. (I did not.)

I didn’t know better. (I did.)

We were trying to teach you. (We were trying to control you.)

It was your mother’s idea. (I agreed to it.)

You’re overreacting. (You are reacting like a human being.)

Below the list, one final line: You owe me nothing. I folded the paper carefully and put it in my bag. “Thank you,” I said. We watched the geese for a while, then went our separate ways.

I did not meet Karen that fall. I didn’t meet her that winter. In February, she texted a photo of a therapy worksheet. She had taken a circle and labeled parts of it “shame,” “grief,” “fear,” “hope.” She didn’t add commentary. She didn’t ask for a response. She just sent the evidence of her work. I put my phone down and looked at Scout and said, “We are all ridiculous,” and he wagged as if he agreed.

In March, I agreed to a call with her. Ten minutes. My timer. My rules. She cried for exactly thirty seconds, then stopped herself and said, “That was about me,” and I felt one brick of my resentment slide half an inch to the left. We talked about weather and recipes and the way certain smells can undo you. When the timer went off, she said, “Thank you for letting me practice.” I said, “You’re welcome.” Then we hung up.

The question of children returned to our table as it tends to when your friends start arranging their work calendars around nap schedules. Brian and I had a long talk the night our friends Max and Priya brought their new daughter over and I held her and felt equal parts awe and panic. “I’m not sure I can,” I said. “Not because I don’t want to. Because I’m afraid.” Brian took my hand. “What I know is this: if we do, we will build the family the way you build your art—deliberate marks. And if we don’t, our life will still be whole.” I cried then, not from fear but from relief, because sometimes the most loving thing a person can do is offer you two okay endings and let you walk toward either.

We didn’t decide that night. We didn’t decide that month. We did decide to become mentors with the nonprofit I had rebranded. I spent Thursday afternoons with a thirteen-year-old named Kiara who liked to draw wolves and believed, with good reason, that adults were weather systems to be tracked, not trusted. We did not talk about my past. We did talk about shading, about trains, about a woman with red glasses who once noticed a quiet girl in a loud room. I told Kiara that kindness can be structural—that we can build it into places like one builds ramps and railings.

One Thursday, she asked me, unprompted, “Do you think people can change?” I said, “I think people can begin. Change is a lot of beginnings in a row.” She nodded like I had given her an equation she could solve.

A year after Frank’s surgery, I returned to Union Station one more time. Not for work. Not for ghosts. For ceremony. I brought a small bunch of daisies because I don’t know what else to bring to the place that held your terror and handed you over to your future. I tucked them between the slats of a bench. I sat. I breathed. I texted Ethan a picture of the ceiling with its wide mouth of light. He wrote back, She still looks the same. She, as if the station were a person. It felt right.

I thought about going home—to the house in Ridge View. I did not. That word was no longer a place on a map. It was a set of people and practices. It was a dog whose head fit exactly in the curve behind my knees when I slept. It was Sarah’s hands in my hair when I was thirty and still needed a mother to say I was good. It was Thomas’s laugh when I made a pun bad enough to count as modern art. It was Brian’s notes on the fridge: Remember milk and, once, Remember joy.

On the first day of spring, I agreed to meet Karen. We chose a small botanical garden in a city that was not hers and was entirely mine. When she arrived, she stood ten feet away and asked, “Do you want a hug?” I said, “Not today.” She nodded. We walked. She didn’t try to fill the air. We stopped at a cluster of crocuses so purple they seemed to insist on a season that hadn’t fully arrived.

She took a breath. “I am sorry I left you,” she said, each word a step. “I am sorry I laughed. I am sorry I surrendered my rights instead of learning. I am sorry I told people you were rebellious when the truth is I was a coward. I am learning how to say sorry without asking to be forgiven.” A robin hopped in ridiculous dignity across the path and for a moment it was just a bird and a path and two women trying to understand the math of regrets and beginnings.

“I accept your apology,” I said. “I do not forgive you today.” Her face did something I had never seen: it softened around disappointment without weaponizing it. “Thank you,” she said. We sat on a bench in silence long enough for the air to shift. When we parted, she did not ask when she would see me again. Later that night, she texted, Thank you for letting me tell the truth out loud. I will keep saying it. Even when you are not there.

I did not reply. I didn’t need to. Sometimes the point of a boundary is not the line but the way the ground stops shaking when you draw it.

Two summers later, I stood on a small beach north of the city with Sarah and Thomas, with Brian, with Audrey and Kiara, with Ethan and his daughter, with a rented grill and a cooler full of lemonade and questionable salads. We had invited Frank and Karen. They declined, which was the right choice. The invitation had been a practice in not hiding. We took a photo where everyone looked like themselves and nobody looked like a shadow of an old story. Later, I printed it and put it next to the framed letter from my art school acceptance, next to the sticky note that said You can stop, next to the list Frank had written.

When we packed up to go, Kiara handed me a small drawing—two train tracks merging into one and then, a little farther down the page, gently parting again, each steady, each heading into its own future. I smiled so hard it hurt. “It’s about you,” she said, shrugging, and then blushed because she had said a tender thing out loud.

That night, I wrote one last letter—not to Frank or Karen, not to Sarah or Thomas, but to the girl I was at twelve:

Dear Jennifer,

You were right that day—to be afraid, to cry, to ask for help, to accept it, to keep saying what happened even when people wanted you to call it something else. You are not lost. You were left. You are not the lesson. You are the student who taught herself a thousand small survivals and then turned them into a life. I will keep you with me, but you do not have to keep standing by that pillar. We can sit now. We can draw. We can leave.

—Megan

I folded it and tucked it inside my sketchbook—the one that holds the darkest pages and also the brightest.

Here is the ending I chose, clear as the station clock.

My parents left me at a train station as a joke. “Let’s see how she can find her way home.” They laughed. I never went back.

Twenty years later, they found me. I did not return to who I was. I did not return to where I came from. I walked forward—into a life I built with people who showed up, with love that didn’t demand a test first, with boundaries that kept me steady and soft at once.

I did go back to Union Station—not to reenact a trauma, but to call it by its name and then call a cab. I stood in the middle of that vast hall and listened. It still hummed, the way places with rails always hum—a sound of leaving and arrival stitched together.

If there is a moral, it is not that families always reconcile or that apologies fix the past. It is this: you get to decide which doors you walk through and which platforms you wait on. You get to choose your fellow travelers. You get to laugh without cruelty and teach without abandoning. You get to name yourself.

And when a text comes in from a number that used to own your fear, you get to read it in a kitchen where a dog leans against your leg, where a partner hands you tea, where you can say, “Not today,” or “Ten minutes,” or “Meet me in the garden,” and all of those can be the right answer.

I was left. I learned the way home. Then I built one.

END!

News

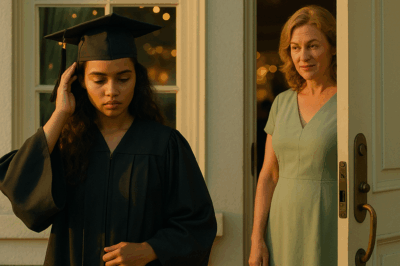

At my graduation party, I was told to wait outside the venue. My aunt smirked, “This is just for close family.” ch2

At my graduation party, I was told to wait outside the venue. My aunt smirked, “This is just for close…

Walk it off. Stop being a baby,” my father yelled as I lay motionless on the ground. My brother smirked while mom accused me of ruining his birthday. But when the paramedics saw I couldn’t move my legs, she immediately called for police backup. The MRI would reveal. ch2

Walk it off. Stop being a baby,” my father yelled as I lay motionless on the ground. My brother smirked…

When I got married, I kept quiet about the $25.6 million company I inherited from my grandpa. Thank God I did because the day after the wedding, my mother-in-law showed up with a notary and tried to force me to sign it over. ch2

When I got married, I kept quiet about the $25.6 million company I inherited from my grandpa. Thank God I…

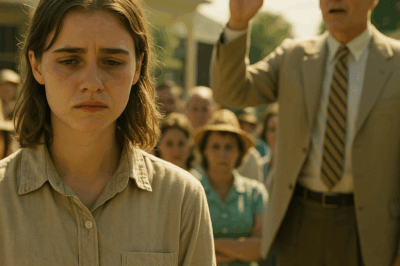

My family made me take the blame and the beatings for my siblings mistakes, calling it tradition. When I finally exposed my father, the so-called hero, he twisted the story and convinced the whole town that I was the villain. ch2

My family made me take the blame and the beatings for my siblings’ mistakes, calling it tradition. When I finally…

At a memorial for fallen firefighters, they called my service dog fake and kicked her. ch2

At a memorial for fallen firefighters, they called my service dog fake and kicked her. Then they ripped my medal…

“I Didn’t Come Here To Sugarcoat Anything. I Came To Tell The Truth. And If That Makes People Uncomfortable? Good.” Tyrus turned a guest appearance on The View into a televised reckoning.

What began as a routine segment exploded into a cultural flashpoint when the Fox News powerhouse called out the panel—live…

End of content

No more pages to load