My Parents Laughed When I Walked Alone To My Wedding, But Their Faces Changed When The Doors Opened. My Parents Chose Dinner With My Brother’s Girlfriend Over My Life — Then My Letter …

Part 1

I stood at the chapel entrance, fingers finding the last stubborn wrinkle in my dress and smoothing it flat as if calm could be ironed into fabric. Through the frosted glass, my parents were right where I knew they’d be: front pew, center, sitting like they’d been appointed to judge the event rather than witness it. My father leaned toward my mother and said it loud enough to float down the hall.

“Can you believe she’s doing this? Walking down the aisle alone—like it’s a statement.”

My mother laughed. Not a nervous flutter. A laugh with an edge, hard as the little pearls at her throat.

“It’s embarrassing,” she said. “Everyone will think nobody wanted to walk her.”

My hands trembled around the bouquet. I tightened my grip until the ribbon bit crescents into my skin, until the white roses steadied in place. My name is Emma. I’m twenty-nine, a social worker at a nonprofit that keeps people from falling all the way through the cracks. I file emergency petitions, hold hands in fluorescent waiting rooms, and sit in kitchens where the only thing louder than the refrigerator is grief. It’s meaningful work. It’s also how I learned to recognize dysfunction even when it’s dressed up and sitting in the front pew.

I am an only child. Growing up with my parents felt like living under a constant, low hum of disappointment. Not drama—just the steady signal that I was not the daughter they’d ordered. They wanted flash. Country-club conversation. The kind of child who marries leverage. Instead, they got me—someone who brings casseroles to families they’ll never meet, who can recite statutes and bedtime stories with the same care, who wears sensible shoes to save a stranger’s apartment from mold.

When I got engaged to Michael two years ago, they made their position a campaign. He teaches literature and coaches debate at a public high school. His family is kind, unconnected, the sort who bring folding chairs and homemade potato salad to every holiday. He does not own cufflinks. He wore off-brand shoes to my parents’ dinner party and discussed a book my father had never read. They decided he wasn’t enough. They told me to call it off. When I didn’t, they withdrew in the way people do when they think their absence is a punishment you can’t survive.

We paid for everything ourselves. We kept the guest list intimate. We picked a chapel with wooden beams and a window that made the late-afternoon light look like a blessing even if you didn’t believe in those. I had made peace with walking alone when, forty-eight hours before the ceremony, my father called and said, “I’m too uncomfortable with this marriage to participate.” It should have gutted me. Instead, something inside me clicked into place. There’s a kind of calm that arrives when you run out of ways to make yourself smaller for people who like you small.

Two hours before the ceremony, I arrived at the chapel prep room with a garment bag, a pair of flats in case the heels started to bite, and enough safety pins to build a bridge. I pinned my veil, fixed my lipstick, and said hello to the woman in the mirror like she was someone I trusted. The organist started the prelude downstairs, notes rising like birds that had waited for this exact weather.

And then voices in the hallway—familiar: my parents. They didn’t know I could hear. My father’s tone was flat, the way he sounded when he’d already decided.

“I still can’t believe she’s going through with it. Walking down alone. Pathetic. People will pity her.”

“They’ll wonder what’s wrong with her,” my mother said. “Why her own father wouldn’t claim her. She did this. She wouldn’t listen about Michael. She was always stubborn.”

I pressed my fingertips to the vanity, took a breath that shook once and then evened out. I did not cry. In my line of work, you learn which tears cost you too much. Aunt Patricia poked her head in a minute later. She’s my mother’s younger sister and the only person in my family who has ever made room without making a point.

“They’re in a mood,” she said carefully, stepping inside and closing the door with her hip. “They keep saying this is a mistake.”

“Thank you,” I said.

“For the warning?” she asked.

“For being here,” I answered.

My phone buzzed. A text from my father: If you go through with this, don’t expect support. This is your last chance to make the right choice.

I put the phone face down, adjusted the comb in my hair, and whispered to the woman in the mirror, “You don’t need them to believe in this. You already do.”

At the doors, I could see them more clearly, my father checking his watch, my mother fussing with her pearls, both of them turned slightly away from the aisle as if the ceremony were happening somewhere else and they were waiting to be invited. I didn’t know then that the moment those doors opened would change more than the temperature of the room.

The music swelled. The doors swung wide. I took my first step. Alone.

My father did not stand. My mother did not stand. They sat rigid in the front pew, faces composed like portraits: a study in refusal. The shift was immediate—guests glanced, expressions caught between shock and anger, hands hovering as if they could make up for what those two refused to offer. The air went tight. My heartbeat took up residence behind my eyes.

Michael was at the altar, sunlight pooling over his shoulders. He saw my parents sitting and something flashed—concern, a flicker of pain—then he looked at me and smiled. It was a steady, real smile that reached his eyes. That smile put my feet on the ground.

And then the room did something I did not plan. Aunt Patricia stood. Michael’s mother stood. A row of friends stood. A family I’d helped reunite last winter rose together as if choreographed by gratitude. The photographer, who knew something about capturing rightness, lowered her camera and stood, too. One by one, the entire chapel rose. Not because my parents did. Because I was walking.

My parents’ faces changed. Not softened. Changed. Like a calculation recalculated and still not coming out the way they wanted. They stayed seated.

I walked through that corridor of people who loved me, past the front pew that loved appearances, and I reached the altar feeling taller than I had in years. When the pastor asked for vows, my voice wavered once and then found itself.

“I choose you,” I told Michael, “always. Even when others don’t choose me.”

I wasn’t looking at my parents, but the words landed where they needed to. Rings, promises, a kiss, and then the release of laughter that comes when a room decides it wants joy more than gossip.

At the reception, Michael and I were embraced like people are embraced when the crowd is made of those who chose to show up. There were heavy arms around our shoulders, ridiculous toasts, and too many photographs of cake on noses. During cocktail hour, Aunt Patricia found me with eyes that apologized for things she had never done.

“They left,” she said. “They said this was a waste of their time.”

It stung. It didn’t surprise me. I went back to our table and kept holding Michael’s hand like a rope I’d climbed to get here.

They returned once. During dinner service. My father walked to our table like he was delivering a verdict.

“We’re heading out,” he said. “This has been…sufficient.”

Sufficient. He didn’t kiss my cheek. He didn’t shake Michael’s hand. He swung the word like a gavel and turned away.

“I’m glad you came,” I said anyway.

“Don’t thank us,” he cut in. “We did this for appearances.”

And then they were gone. Something broke and something lightened; sometimes that happens at the same time. Michael squeezed my hand. Our friends at the table—fierce, protective—leaned in closer like a wall you can count on.

When the last song played and the lights came up, I felt two things layered over each other like translucent pages: grief for the parents I wanted and a clean, hard edge of resolve for the life I was going to have without their permission.

Part 2

Two weeks after the wedding, my father’s accountant called. People who have accountants do not always have decency; they have scripts. He explained, neutral as a calendar reminder, that my trust fund had been frozen. My father had invoked a “family moral standards clause” buried deep in the document. The clause had never been used. It was vague enough to mean whatever the holder wanted it to mean.

I stared at my coffee mug, at the lipstick print on the rim, at the way sunlight turned the steam visible. “He’s freezing my inheritance because I married someone he doesn’t approve of,” I said.

“I can’t speak to motives,” the accountant replied. “I can only relay the action.”

I called my father. My voice was steady. My hands were not.

“You’re taking it away because I married Michael?”

“You made your choice,” he said, satisfied. “Live with the consequences. No trust, no financial support. You’re on your own.”

My mother got on the line. “We’re done investing in your poor decision.”

That was the moment the last curtain fell. The money was never about generosity. It had always been a leash. I hung up, sat at our little kitchen table, and looked at the list Michael and I had made of bills, paydays, and the months that look longer from the inside.

“We can do this,” Michael said, pulling his chair close until our knees knocked softly. “We’ll be tight for a while.”

He picked up tutoring gigs three nights a week and Saturday mornings. I took extra hours, then extra-extra hours, covering emergency intakes and home visits no one else could stomach. We rerouted what we could: canceled a weekend away, delayed new tires, learned to make a whole chicken stretch four completely different meals. We did the math and found space for laughter between the lines. Instead of cracking us, the pressure fused us. We were a team, the kind that doesn’t keep score.

I stopped calling my parents. I stopped trying to edit myself in hopes they’d prefer a new draft. I moved all that energy into the life we were building, brick by careful brick.

What they didn’t know was that I had been documenting everything since the engagement—every ultimatum, every “last chance,” every remark about “appearances.” Screenshots. Dates. Times. A timeline of the way love had been repurposed into a tool. Aunt Patricia had suggested it, gently, months back: “Just in case.” I didn’t know what in case meant. I kept the records anyway.

Six months before the wedding, I had made an appointment with a trust and estate lawyer because my work had taught me not to walk into storms without a coat. The lawyer—sharp suit, kinder eyes than she needed for her job—explained the document my parents wielded like a magic wand. “He can freeze disbursements,” she said, tapping the text with a pen, “but he can’t keep it from you forever. The principal becomes accessible at thirty, no conditions. He knows that.”

I was twenty-nine. Two months from thirty. It felt like standing in a doorway and seeing the next room but not yet stepping into it.

I also hadn’t told my parents that I’d been promoted to director of my department. The raise was real. The work was heavier, but I’d already been carrying more than my share. We had three months of expenses tucked into a savings account Michael and I didn’t talk about much because we were superstitious in the way people are when they’ve learned life can hear you brag.

There was one more thing. A publisher had reached out, curious about my work with families and the way I seemed to survive the job without losing my softness. They were interested in a book about emotional manipulation inside families—how it looks, how it sounds, how to name it so you can leave a room before it collapses. The contract was being shaped. I hadn’t told anyone. Not because I was hiding; because I hadn’t decided whether I wanted to braid my private life into a story that would belong to other people, too.

Michael’s family filled in the spaces mine had left. His mother sent soups that could fortify a week and texts that read like hugs. His dad asked about our radiator and showed up with a toolbox like a magician. When we visited on Sundays, they made a point of sending us home with leftovers, not because we couldn’t afford groceries, but because kindness tastes better than anything you buy.

My parents grew louder in other people’s kitchens. They told their version to whoever would listen: that I was ungrateful, that Michael was a taker, that they had tried to save me and I’d insisted on drowning. Some relatives took their side. Others didn’t. The ones who didn’t called me quietly, the way people call from a room they don’t want the host to notice.

Then my father escalated. Michael came home one Thursday with a face he reserves for emergencies.

“My principal called me into his office,” he said. “Someone phoned the school and made insinuations about my…character.” He didn’t repeat the words—they were that ugly. “The caller wouldn’t leave a name.”

We didn’t need one. I felt something in me shift. A cold, clean gear clicked into place. This was no longer a heartbreak. It was a hazard.

I called the trust lawyer the next morning. “What do I do when a person is trying to set fire to my life?” I asked.

“You document everything,” she said. “And then you put up a wall.”

We invited my parents to our apartment for a conversation. Not a negotiation. A conversation with an exit built into it. Michael sat beside me on the couch. Aunt Patricia and her husband, David, waited in the next room, not as reinforcements, but as a place to land if the floor gave way.

My father walked in like he was giving us a chance to repent. “This better be about you coming to your senses,” he said. My mother, behind him, smoothed her blouse like she was preparing for a photograph.

“I asked you here because I need you to understand something,” I said.

I placed a folder on the coffee table. Inside: their texts, the trust lawyer’s letter, notes about the call to Michael’s school, my promotion paperwork, the draft book contract with lines highlighted in yellow. My father’s face went pale the way paper goes pale when you hold a match near it.

“You tried to control me with money,” I said. “You tried to sabotage my marriage. You tried to interfere with my husband’s job. I have everything documented.”

“This is ridiculous,” my mother began. “You can’t—”

“The trust freeze violates the document’s terms,” I continued, steady. “You can’t punish me for marrying someone you disapprove of. Not legally. I’ve spoken with an attorney.”

“You wouldn’t dare take us to court,” my father said.

“I don’t want to,” I answered. “But I will if you force me.”

“We’re your parents,” he said, resorting to the anthem people sing when they’re out of arguments. “You owe us respect.”

“Respect is earned,” I said. “You haven’t tried to earn it. You’ve demanded it while treating me like a possession instead of a person.”

I slid the book contract closer so they could read the working title. “I’ve been offered a publishing deal. It’s about emotional manipulation in families—what it looks like, how to name it, how to escape it. My attorney advised me not to sign without giving you a chance to change your behavior. So I’m giving you this chance. If you continue, I will tell the truth in a voice that carries.”

“You can’t write about us,” my mother whispered, going white.

“I can,” I said. “And I will. Unless you stop. I’m not asking for apology balloons and a parade. I’m asking for boundaries you honor. If you can’t do that, we’re done.”

I stood. “I turn thirty in two months. The trust becomes mine, regardless. I have a career. A marriage that’s a team. A life that doesn’t require your permission. I don’t need your money to survive.”

Silence filled the room like water filling a glass. Finally, my father said, “If you do this, we’re done.”

“We’re already done,” I said. “I’m just acknowledging it.”

They left. Michael took my hand like he was holding a bird he didn’t want to frighten. Patricia and David came in and sat with us until our hearts came back down to a resting speed.

Six weeks of silence followed. Then my mother sent an email with a subject line I recognized from childhood: Let’s Talk. I agreed to meet at a coffee shop. Neutral ground. The conversation was awkward, knees and elbows of sentences hitting each other and leaving bruises. They did not apologize outright. They did not bless my marriage. But they admitted they’d been harsh. My father unfroze the trust. The relief I felt surprised me less than the disappointment. I had wanted them to be different people. Instead, I was becoming a different person.

I did not remove the book deal from the table. I let it sit there, a boundary in writing. Our relationship shifted into something cautious and transactional. Courteous, not close. I made peace with that space and planted flowers there.

Part 3

Turning thirty felt both arbitrary and holy. On the morning of my birthday, I woke before my alarm. The light in our apartment was the gray-gold of a day deciding to be kind. I brewed coffee and didn’t add the extra teaspoon of sugar I used to throw in when I needed courage. I opened my laptop and saw the number that had been the fulcrum of so many fights: the trust principal, mine without condition. I closed the tab. I didn’t touch a cent. Security is sweeter when it’s not the only reason you can breathe.

Work thrummed. As director, I took on the cases with the sharpest edges. I supervised staff who wanted to save everyone and taught them how to save themselves, too. I learned to end my days with a ritual that separated survival from dinner: I washed my hands slowly, counting to twenty, watching the hot water gather around my knuckles and carry the residue of other people’s emergencies down the drain.

In supervision one Thursday, a new social worker cried because a teenager called her names and then begged her not to leave. “How do you keep doing this?” she asked, mascara smudging into two small storms under her eyes.

“I remember that the help we offer is kindness, not control,” I said. “We don’t get to decide for people. We just make sure they have real choices.”

At home, Michael was promoted to department head. He brought the news in with the mail and a grin that made him look fifteen. We celebrated with a fancy pizza we ate on plates because that’s what adults do when they feel like kids. We put money in a savings jar labeled House and promised ourselves we’d only touch it to pay for inspections and repairs we could point to with a flashlight.

We went to therapy—together, because we’re not superheroes; and separately, because I had a lifetime of learning to unpack. My therapist offered me words I didn’t know I needed: vigilance, fawning, boundaries that are more than a sign you tack on the wall. “You’ve been trained to be grateful for crumbs,” she said gently. “You are allowed a meal.”

Aunt Patricia remained our steady. She came over on Thursdays with a bag that always contained at least one splendid thing I wouldn’t buy for myself: real cinnamon, a candle that smelled like rain on hot sidewalks, a scarf the exact shade of the lake we’d someday live near. She told me stories of my mother from when they were girls, before country clubs and rules, before a laugh could turn into a weapon. It did not excuse my mother. It explained her enough that I could put down a piece of anger and walk away lighter.

My parents and I existed in a truce made of careful sentences. They came to dinner once, looked around our small apartment, and didn’t say it was small. My mother complimented the rosemary plant on the windowsill as if it were a child. My father made a comment about a case he’d read in the paper, then paused like he wanted me to know he was thinking about my world. I let that land. I did not mistake restraint for transformation.

And then the past tried to knock again. A distant cousin called to say my parents were telling people I’d threatened them with a book. “They’re embarrassed,” she said, her voice doing the flinch it always did when she delivered news that might explode. “They say you’re holding them hostage.”

“I gave them a choice,” I said. “I chose myself.”

That night, I sat at our table and wrote a letter. Not to them. To myself at twenty-one—the girl who would have abandoned the aisle if her father threatened to sit. I told her the truth I wished I’d learned sooner: you can love your parents and refuse to obey them. You can love yourself enough to walk anyway.

I tucked the letter in a drawer with my passport and our house-savings envelope. I slept like someone who had given a gift to a person who needed it badly and on time.

Michael and I went house hunting. We found a small colonial with a porch barely big enough for two chairs and a body of water that held the sky like a promise. The inspection report read like poetry after the apartments we’d lived in: roof good, foundation sound, windows stubborn but loyal. We closed in late spring, using our own money. I told my parents about the house the way you tell people news you don’t need them to bless. They looked around when they visited and said nothing, and for once, their silence helped.

In June, my mother emailed asking to meet again. “I want to understand,” she wrote. At the coffee shop, she sat forward, elbows on the table, as if leaning could make her listening more believable.

“I was cruel,” she said, hands sliding over each other, searching for a place to rest. “I cared about the wrong things. I still…care about some of those things. But I don’t want to lose you.”

“You never had me,” I said. “You had a version of me who was very busy trying to be what you wanted.”

“I can try,” she said.

“Trying looks like respecting boundaries,” I replied. “It looks like not calling my husband’s school. It looks like not using money to make a point. It looks like you standing when I walk into a room.”

She nodded. “I can do that much.”

It wasn’t an apology. It was a beginning that knew its place.

When my father joined us, he didn’t talk about feelings. He talked about a book he was reading. Halfway through his summary, he realized what he was doing—meeting me where I live. His mouth twitched upward. Mine did, too. It was a small, strange kindness. I took it, not as proof, but as evidence that people can choose different sentences.

The book contract waited like a door I could open if the house got smoky again. The publisher checked in twice. I told them the truth: I wasn’t ready, not because I was afraid, but because I wanted to write it with the steadiness that comes after the storm, not with the shards still in my hands.

Part 4

A year passed the way years do when you’re busy building: marked by seasons you finally have time to notice. The rosemary exploded into a small hedge and then gave itself to potatoes and lamb. The porch chairs groaned when winter arrived and then remembered their purpose in spring. We painted the back bedroom the color of quiet and put a desk there where I wrote case notes that no one would ever read as literature and a handful of paragraphs that might someday become the book.

On our first anniversary, we returned to the chapel. The sexton let us in and turned on the lights like dawn. The wooden beams looked less like a ceiling and more like ribs protecting a heart. Michael and I walked the aisle together. When we reached the front pew, I sat where my mother had sat and tried to feel what she had felt. I couldn’t. I could only feel my own breath, my own steady pulse, and the way Michael’s hand found mine without looking.

“Do you regret walking alone?” he asked softly.

“No,” I said. “I regret waiting so long to learn I could.”

We left a bouquet on the windowsill for whoever needed it next.

At work, I launched a training on coercive control for new staff. We role-played conversations where love hides behind rules and money introduces itself as help. We practiced saying, “I believe you,” and then practiced saying it again to the person in the mirror. I watched young social workers straighten under the weight of language they could lean on.

One afternoon, a client asked me if my family understood me. She had a bruise in the shape of a ring on the back of her hand where someone’s apology had landed. “Not at first,” I said. “Sometimes not now. But I understand myself. That helps.”

In late summer, my parents accepted a dinner invitation at our house. I made lemon pasta with too much garlic and didn’t apologize for the smell. They arrived on time. My father brought a bottle of wine with a label I googled later out of curiosity and then decided not to care about. My mother brought a pie that tasted like practice. We set the table, ate, and talked about ordinary things: a neighbor’s overgrown azaleas, the city’s plan to fix the potholes by the school, a student in Michael’s class who loved poetry so much it made him forget to be cool. The night was an exercise in staying on the path. When they left, my mother hugged me. Not a hospital hug. A real one. It lasted exactly one beat longer than politeness.

“What do you think?” Michael asked after the door closed.

“They’re trying to learn a new language,” I said. “I won’t correct their accent. But I won’t pretend not to hear it, either.”

In the fall, the publisher called again. This time I said yes. I wrote the book in the early mornings, when the house was quiet and the lake outside our window reflected the sky without comment. I did not write about my parents in detail. I wrote about patterns. About laughter used as a blade. About standing alone and the moment a room stands with you. I wrote about the letter I wrote to my younger self and how some letters are really rescue ropes you send backwards through time.

When I turned in the manuscript, I drove to the chapel and sat in the back pew. A couple was setting up flowers; the florist nodded at me the way people nod at each other in holy rooms. I did not need the book to be a bestseller. I needed it to be accurate enough that someone would read a sentence and think, I am allowed to walk.

On the day the book came out, Aunt Patricia hosted a small gathering on her porch with iced tea and a cake that said Well Done in frosting that leaned to the left. My parents arrived late. My father stood for me. My mother did, too. It was a small act that landed big. They’d missed it at the chapel. They learned it now. It did not erase anything. It wrote over a corner.

Months later, a woman approached me in the grocery store cereal aisle. She touched my arm like you do when you’re about to say something that matters.

“Your book,” she said, “made me leave a table where I was begging to be allowed to stay.”

I nodded. “I’m proud of you,” I said, and I meant it in a way that felt like a blessing.

There’s one more thing to tell you because stories deserve endings that admit the cost and the reward.

On a rainy Tuesday, the kind where the cloud sits low and the road gleams like a secret, my mother called and asked to come over. She sat on our couch and held a mug like a talisman. For a long time, she said nothing. Then she told me a story I had never heard. She was twenty-three, newly married, invited to a dinner with people who cared about the kind of social gravity you can’t measure with science. She had a cousin in the hospital that night. She asked to leave early. My grandfather told her appearances mattered more than emergencies. She stayed. “I chose dinner over someone’s life,” she whispered. “I have been trying to make that choice worth it ever since.”

“You don’t have to keep paying for a decision you regret,” I said.

She nodded. “I know. I just don’t know how to stop.”

“You start by standing,” I said, half smiling. “You start by standing when your daughter walks in a room.”

She laughed then, soft and real. “I can do that much.”

When she left, I stood at the door and watched her cross the porch. She did not look back. I didn’t need her to. We were learning a new choreography—one where no one controlled the music and everyone could choose to dance or to sit without punishing the other.

We did not become a close family. We became a careful one. Holidays were quiet and specific, built of moments that didn’t demand forgiveness to function. Sometimes, after pie, my father would stand and take the plates to the sink without being asked, and I would notice and file it under Things I Never Expected.

If you need a single image to keep, let it be this: the chapel doors opening; the first step alone; a room deciding to rise; two faces in the front pew staying seated and changing despite themselves; the aisle longer than it looked and then short enough to cross; a promise spoken not just to a man at the altar but to a woman in the mirror; a life built afterward, not out of spite, but out of relief.

Walking alone taught me something fundamental: I was always enough. The laughter behind me could not change that. The room standing around me made it visible. The letter I wrote to my younger self sealed it: You don’t need permission. You never did.

And if you’re the one at the doors—if you’re steadying your hands, if you can hear people in the front pew deciding whether you deserve a witness—listen carefully. The music is for you. The aisle is yours. You can walk. Even alone. Especially alone, if that’s what it takes to arrive at a life that is, finally and completely, your own.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

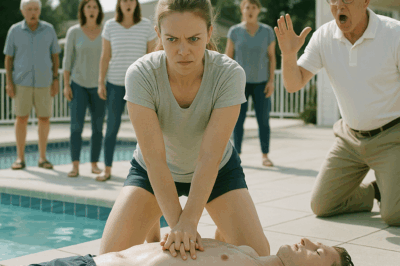

HOA President Tried to Stop CPR… She Never Expected What Happened Next

HOA President Tried to Stop CPR… She Never Expected What Happened Next Part One: Welcome to Sunny Meadows I…

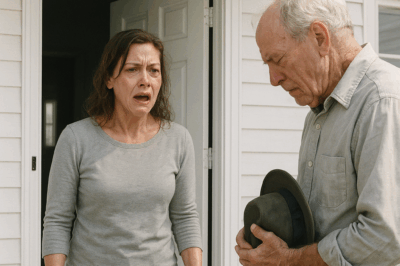

My Dad Kicked Me Out Over a Secret, 13 Years Later, He Knocked On My Door and…

My Dad Kicked Me Out Over a Secret, 13 Years Later, He Knocked On My Door and… Part I…

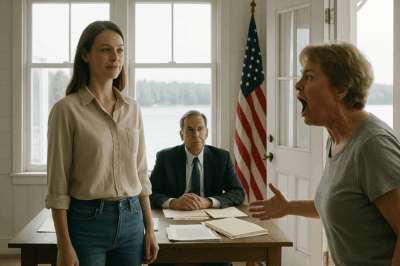

CH2. HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside

HOA Karen Busted Into My Lake Cabin — Didn’t Realize I Was Meeting the State Attorney General Inside Part…

CH2. “May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record

May I Take A Turn?—The SEALs Didn’t Expect The Visitor To Smash Their Longstanding Record Part I The sun…

CH2. Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL

Three Trainees Confronted Her in The Cafeteria — Moments Later, They Found Out She Was a Navy SEAL Part…

CH2. “You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader

“You Can’t Enter Here!” — They Had No Clue This Woman Would Become Their Military Leader Part I The…

End of content

No more pages to load