My parents invited me to a fancy family dinner with all my relatives. Then my father stood up and announced to everyone, ‘We’ve decided to cut you out of the inheritance. You’ve never deserved it.’ Everyone laughed and agreed. I smiled, took a sip, and quietly left. 2 days later, complete family chaos

PART 1

The chandelier hummed a little like an old machine and split the room into shards of light. Crystal pendants flashed on the polished mahogany table. Around that table were the faces I had watched a thousand times in reflections, the same faces that had praised or dismissed me depending on the weather of their moods. They wore familiar armor: tailored suits, pearls, an assortment of watch straps and cufflinks that declared pedigree in a language the rest of the world might not speak but which, somehow, always used me as a footnote.

My father stood at the head, hand on my mother’s shoulder, face smug and absolutely pleased with himself. That smile was the sort that had never had to apologize for anything; it was lacquered, as if time and good marriages had fixed it into place. He lifted his glass, tapped it confidently. Silence fell for a breath. Everyone loves a good speech, especially when it confirms what they already suspect.

“We’ve made a decision,” he said, as if making decisions were the family’s favorite pastime. His voice was loud enough to fill the high ceiling. The conversation around us dipped; a murmur like the tide pulling back. He looked at me the way he had looked at me the day I’d announced a job promotion ten years earlier: with the bland combination of pride and the knowledge that it was mostly convenient for him.

“We’ve decided to cut you out of the inheritance.”

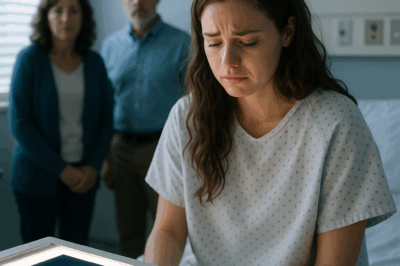

It was not the words that skewered me. It was the sound of the room agreeing—an immediate, collective laughter, not the startled, embarrassed kind but that cruel, comfortable laughter of people who have rehearsed cruelty as a dinner-party anecdote. My cousins raised their wine glasses like clocks striking, my uncle guffawed as though he’d been waiting for this exact punchline for years. My mother’s face did a thing I’d seen a hundred times—part offense, part performance—and the diamond bracelet on her wrist flickered like a confederate flag in a small wind. The same bracelet I had bought her, back when I still thought love and gestures were the same currency.

I held my wine, let it warm in my mouth. Taste can be a good anchor in storms; the tannins dulled the immediate shock to a manageable throb. I smiled. My smile was deliberate and calm—an odd little thing, almost a courtesy.

“You’re right,” I said, standing slowly as if the tablecloth were a map I had traced my fingers over for years. No one reached out, no one tried to catch me. Their laughter continued for a half-breath longer, and then I walked out of that room as though I were leaving the theater after the curtain call on someone else’s play.

They thought that cutting me off would be the end of me. They couldn’t see past the glitter of the meal; they didn’t know which threads I had been quietly weaving into a safety net for years. That night I slept with familiar sheets and a new sense of calm. It’s a strange thing, the way anger can compress into a cold, focused pressure that doesn’t burn you up but alters the architecture of your thinking. I felt something like clarity: if they had chosen to exclude me, then they had given me a choice in return.

They had always believed family and business were one seamless enterprise. My father had taught me to read balance sheets before I could read novels. I learned to love ledgers not because I wanted to—but because they had been my language. He taught me phrases in the way people teach prayers: “Business is family,” he’d say, patting my shoulder. “And family is business.” It’s not the most benign of doctrines. It becomes a method of deciding whose value counts.

When I finished university—top of my class, but that mattered less at home than the way I made the spreadsheets sing—I returned to run the family accounts. I cleaned up debts hidden like rags shoved under floorboards, negotiated deals, and created systems that made the company appear cleaner and sturdier than it often was. I built password protections and named numerous shell entities not out of greed but out of professional fear: for the company, yes, but also for the people who relied on it. I literally held the keys: every contract, every spreadsheet, every compliance memo. They assumed that because I was obedient and competent, I would always be there to fix whatever they broke.

At night, I watched them sleep in the same expensive house they were now so terrified to lose. I remembered how my father’s voice often told me that loyalty would be repaid in kind; how family would be safe, guaranteed. That belief was woven into my bones. I believed, naively, that the care I put into the company would be reciprocated the way one expects warmth from a hearth: as law.

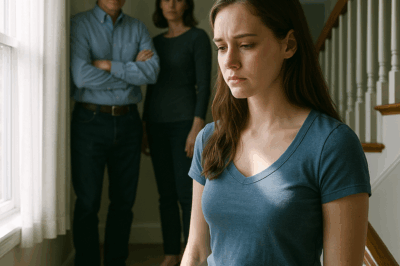

Betrayal, when it finally arrives, is rarely a single violent event. It’s the accumulation of little erosions. The first time they had a meeting and I wasn’t invited, I explained to myself that it was less critical: “executive decisions are sometimes hush-hush.” Then they started whispering when I entered the room. There were more “family-only” dinners. My name began to show in places where it was crossed off with a neat, indifferent hand. I found, once in a flicker of the night, a draft will with my name scrawled out—the same hand that had written my name into holiday card lists years ago now scrubbing it away. In its place: Ethan and Clare—cousins who saw a spreadsheet as a nuisance and could barely spell the word dividends.

The feeling changed inside me from hurt to a quiet, efficient resolve. I stopped wanting to argue. What good does tearing someone down with words do when you already know you won’t change their mind? I began to plan in the same way I had built the company: carefully, with precise steps. I didn’t want to wreck them with scenes. I wanted the architecture of the house to reveal its own rot.

I am not a criminal. That point matters to me. My work was legal, often dullly administrative, but I had always been careful to create legitimate structures. Years before the dinner—years of watering down pride in exchange for career hours—I had set up dormant entities and arrangements for precisely the sort of contingency that now lurked in the portraits on the wall. There were subsidiaries no one had touched because they seemed irrelevant: an emu-habitat investment in a different jurisdiction (ridiculous on the face of it), a minor holding in a logistics company, an unremarkable trust used for employee benefits. I had protected them not because I had the morals of a saint, but because I had foreseen what happens when power consolidates and forgets gratitude.

So I moved things quietly. When their whispers on their private calls turned darker, when the smell of a changing will reached me as plain as coffee steam, I placed certain assets into legal structures under my own name—or rather, under entities I controlled. I also set triggers so that if my name was forcibly removed from decision-making, certain automatic transfers would execute. It’s complicated in the way modern corporate structures are complicated: layers upon layers, written by lawyers with patience. I can explain it in terms anyone can understand—locks and keys, with me holding the master key and choosing, for the first time, not to give it back to people who had already decided I was expendable.

The night before the dinner I printed a file. It was a simple, unassuming packet: a trail of internal memos that, when assembled in the right light, made the current version of my father’s empire look negligent. I left a digital breadcrumb for auditors, a line so small it would prove to be the match for a very dry woodpile. The next morning I laid my napkin on the table, the same table as always, and when my father spoke into the silverware-laden air it was as if he were ringing a bell to call vultures. He invited them in with the ease of someone who thinks his name is indelible.

Their laughter was a kind of finality. They thought it would sabotage me socially, a public shaming to justify their decision. In front of the extended family—cousins who sniffed at my “practical” haircut, aunts that never liked my new chairs—their cruelty looked like civility: for a moment, I was the spectacle. I let them have that moment. I sipped my wine, walked out, and did the work that would make that night mean something.

The first day after the dinner, the company accounts were frozen. Compliance flags lit up like little alarms across the corporate dashboard, and the bank put cards on hold. The regulators had been tipped off to suspicious transfers. My father’s signature—which had always been the monolith of their stability—was now annotated in reports with questions. The press does not like nuance; scandals marry drama with search engine results and make problem solvers like my father appear, overnight, like men with bad judgment.

Panic is a peculiar thing to witness when you built the architecture. You watch as people smash the vases they swore were tied to their identity. My cousins, who could once only tell you the names of the top designers for cufflinks, were suddenly trying to negotiate liquidity like men who had invented the whole concept of fiscal prudence in the prior hour. They called me, bless their small sudden humility, asking for help. My father texted, “What did you do?” as though he had not, for years, taught me how to untangle messes.

I drove back to the estate that evening. The long driveway—iron gates that once made my heart swell with a strange loyalty—suddenly felt like an auditorium of exposure. The portraits watched like judges. My father was in the study surrounded by papers, his face ashen. He is a man who made his choices; he’s also a man who will not easily admit how fragile those choices were. When he saw me, the first word from his mouth was “You destroyed us.”

“No,” I said evenly. “You did that when you forgot the hands that built this place.”

He called me, then, the son he always imagined: the obedient, useful child who should be grateful enough to be tolerated. The irony was quiet and clean. I left an envelope on his desk, a legal expression of my intentions. The remaining assets I controlled were now paraded under a new banner: one with solid legal seals. I had not stolen; I had simply chosen to aggregate and protect the value I had created. In the morning the media circulated a headline: “Family Business Under Investigation.” The word scandal is such a neat, efficient blade.

Within forty-eight hours the house had not caught fire in the way of flame. It caught fire in the way of revelation. News trucks loitered like scavengers. People who had once laughed at me for being overly cautious were suddenly the ones who asked for the kind of help only I had been trained to give. Investors called the board; auditors demanded documents, subpoenas were issued. The company that had seemed so invulnerable showed the brittle underframe I had always suspected existed.

My father’s empire buckled in the time it takes for afternoon tea to cool in a porcelain cup. I watched it happen without glee. There is a moral difference between satisfaction and joy. I felt satisfaction—a long, clean relief—not because I wanted them to suffer but because they needed a consequence to wake them from their delusion. They had been coddled by their own certainties for years. Punishment, in the form of the legal and regulatory world’s attention, was their rude education.

Later, when my father says that I ruined him, I hear the voice of a man who cannot reconcile his image with the actions that led to its ruin. Sometimes I wonder if he had ever considered that treating people like instruments yields a synchronous decline in those very instruments’ inclination to play music for you.

At night, after the reporters left for a while and the house settled into an angry, lonely shape, I walked around the property. I stood where the lawn met the old oaks and watched the estate breathe. I felt oddly free. It wasn’t relief at another’s pain. It was a release from having to pretend that their values were my own.

PART 2

The second day brought the avalanche. Regulators and journalists were not the only elements to move. Old partners withdrew, noting fiduciary risk. Banks tightened credit. There were calls to the board demanding immediate accounting, and in many cases, those involved found that their signature authority had been, legally, constrained. The accounts people tried to access were showing zeroes in forms they did not understand. Some of those zeros had always existed in a way they’d just chosen not to see.

My father’s phone filled with the frantic voices of men who had taken him for a kind of god. He had always argued so confidently that his authority was unassailable; as the truth leaked and then gushed into public forums, the certainty evaporated. My mother, who had always been a study in composed agitation, sat on the sofa one afternoon watching a thread of comments about “mismanagement” scroll on her tablet. Mascara smudged, she read with an expression that had the faint flavor of bemusement turning to dread.

“Call your son. He must fix this,” she said finally, and in that moment I realized that the same woman who had once performed a troublized rebuke and orchestrated that dinner was now reduced to an offer: gratitude in exchange for escape. She had always been good at timing and presentation; she just hadn’t considered that I had been timing my own.

I was under no moral obligation to solve for them—after all, they had chosen to cut me off in the most public way—but the human element is always messy. I am not a heartless person. The company’s employees—bookkeepers, the factory workers who sorted things in a warehouse, the people who depend on payroll—were not the authors of the family’s petty cruelty. Somewhere in the calculus I had decided I wouldn’t be the one who caused others to suffer because of their leadership’s crimes. So I did assist a bit— quietly, with counsel. I coordinated a few emergency protocols to keep payroll running for a week. That is another kind of power: choosing the people you care for and ignoring the patrician tyrants who expect you to be a miracle worker.

Meanwhile, my cousins who had laughed at the table were suddenly awkwardly reading memos they had never learned to comprehend. They called me, all of them, in a repetition so absurd it could almost be called theatrical. “Please help,” one said, his voice reduced to a whine that had not existed in his vocabulary until his assets were at risk. “You’re the only one who knows how the ledgers connect.”

“Why should I help the people who wanted to erase me?” I asked him.

“You’re family,” he said.

The word felt cheap to me. Family had been a script: show up, be small, run the last-minute errands at weddings, be pleased when some praise leaked into the Venn diagram of your life. They had been content with my compliance and only insulted me when it suited their narrative. No. My assistance came at a price: transparency and accountability. For any help I provided, they had to agree to independent audits and signed disclosures publicly posted. The cousins choked on their arrogance and swallowed the contract. Even as they hated me for it, they also needed me to render the accounting of what had gone wrong.

On day three the board called an emergency meeting. Cameras found their way into the lobby. Investors who once nodded politely in the corner issued calls for new leadership. My father—formerly unassailable—sat in the middle of it like a small, perplexed man in a big suit. He looked like someone watching a show about someone else’s life, and it was not a sympathetic sight.

There was ugliness I could not control. Some of my relatives tried to make narratives that would shift blame away from their incompetence. They called for scapegoats, noting witch-hunts and political maneuvers. My presence was described as “venom” or “treachery” depending on who was asked; the press found it delicious to spin both angles: the prodigal genius turned saboteur, or the malcontent who ate the family from within. Humanity has a hunger for simple stories. The truth likes to be complicated, and my truth refused the tidy arcs.

A number of items were seized to satisfy regulatory interest: folders, hard drives, sealed boxes with legal notation. Memories of holidays—cheerful, mildly ornate—began to look, in news footage, like an indulgent past that had rotten under the surface. People who had laughed at my name were now quoted in articles as “sources close to the family,” the kind of phrase that marks the death of privacy. Our family’s private business became a public cautionary tale: how dynastic thinking and entitlement can lead to structural failure.

There were personal ruptures, too. At a funeral luncheon for a great aunt — who had been neutral on all matters but loved order — relatives pretended normalcy until a reporter asked a pointed question about transfer deeds. A table of men who had always spoken with a practiced ease rose and left en masse. A woman who had once cooed when I made coffee for her at breakfast now avoided my gaze.

I will not say I wanted them to burn. I will say I wanted them to realize the cost of their choices. Plenty of times, in the dead watches of the night, I imagined them humbled but whole: a father who sits and reads books and understands his child’s value beyond spreadsheet dividends. I wanted them to be able to show decent faces in the world. That was given to me as hope. It did not always pan out.

The good news is that disruption invites introspection. My father, for his part, had moments of clarity. Once, when the house was quiet and the portraits seemed to be inhaling in sympathy, he approached me.

“You could have destroyed everything,” he said one afternoon, voice thin. He was a man caught in the net he had woven.

“You built something fragile,” I answered. “You built it on the assumption of forever.”

There was shame on his face then—genuine, raw, something that might have been the beginning of repair. But not every man can swallow his pride. Some grow rigid, retreating into whatever remains of authority, and some retreat into buying apologies and hiring counselors with expensive brands. My father tried both. My mother cried. My cousins tried damage control with lawyers.

Within a month a set of legal processes came down: audits, fines, even a criminal referral in certain jurisdictions. The company’s market value cratered; jobs were at stake, and there were layoffs. I sat with that reality like a person sitting with a pragmatic problem: the same way I would balance a budget, I balanced the human cost. I forced myself to be humane about severances and to negotiate extended benefits where possible. You cannot rebuild trust with a spreadsheet alone, but you can at least make sure people have the means to live after a corporate collapse.

Then, slowly, the weather shifted. A new CEO came in with a clean slate and an annoyingly optimistic haircut. She had a plan and a way of speaking that implied fixing things was a kind of craft. She didn’t need my approval; she needed the documents I had locked away. We spoke once in a conference room, the kind with glass walls and a view of honest sky.

“People will hate you for a while,” she said, matter-of-fact.

“Let them.” I was not flattered by her assessment. “Do you think this is all on me?”

“No,” she answered. “But you hold what matters.”

We made an arrangement: I would help transition certain operational things if the company would commit to a structural clean-up and to a public audit. My father, in declining health (a symbolic, not literal phrasing; his pride was aging him), agreed to a mediated program. There was no cinematic reconciliation—no big apology on the steps of the courthouse. There were signed agreements, sealed documents, and, most importantly, a public record that could not be whispered away during family gatherings.

The house lost some of its luster. Portraits were boxed; the library, which my father loved more than his suit racks, was catalogued with a sober list. Occasional calls would come from relatives, complicated as any habit. Some were small apologies, nervous and graceless. “I was wrong,” one said in a message that read like a child learning a new word. Another sent flowers with a note that read, “We missed you.”

Those gestures were not actual absolution. They were the weather this landscape occasionally produced. For me, there was a new landscape. I moved into the small blue house I’d bought on the edge of town. It is the house that fits. Lavender grows in the back and most Sundays there is a pot of something cooking on the stove that is not intended to impress anyone. Friends—real friends—come and sit at the mismatched table. A neighbor brings over a pie; another brings over a plant. People who do not expect perfection but show up. There’s a kind of communion in this which tastes better than the silver my relatives used to rattle.

I did not become cold-hearted. I merely became precise. I arranged the charity to which I donated money, ensuring the employees who had been at risk during the collapse were cared for. I started a small fund to help workers retrain. I did this quietly; the press will say I was trying to avoid optics, and they would be right. I wanted the work to matter more than the applause.

The thing about families like mine is that they assume permanence. They think that because a name has been repeated for generations it is a kind of immortal incantation that wards off consequences. They are wrong. The truth is that institutions are fragile. They rely on recognition and trust, and when those erode, the structure becomes brittle. Right where I had once been an instrument for their power, I became a steward of a different value: accountability.

Two years later things had settled into a new tenor. My father had been compelled to resign. My cousins had split into groups: some who found humility, others who vanished like people ashamed of their own shadows. There were awkward family holidays where my name was still spoken but in a tone that had the sound of concession. Occasionally, Mom would call. Our conversations now are like seeing someone learning a new language. It is slow and halting, with surprising vocabulary, and sometimes painful honesty. There are things she has apologized for; there are things she has not.

There’s also a deeper peace for me. The inheritance they thought to deny me was, in the end, not about money. It was never about money. The inheritance I had meant to inherit—if family had not been an enterprise of cruel convenience—was recognition: to be seen as belonging without an economic calculation. When they tried to take that away, they revealed to me how much that “belonging” had never existed. In tearing down their assumptions, I claimed a different inheritance: freedom.

I wake up in my blue house and make coffee. I walk the lavender, I meet people who bring me real news about their lives. I mentor a handful of younger accountants who are stunned at the idea that spreadsheets can be a tool for justice as well as profit. I am not applauded in tabloids for, what, some kind of theatrical revenge. I am thanked by people whose names are not famous.

Sometimes my father and I meet over documents because it is necessary. He calls with a question about the estate tax schedule, and once in a while, the old tight, familiar tone returns in his voice. We talk like professional men tied by a complicated history. He knows, more deeply than before, what it means to lose the assumption of unconditional loyalty.

If there is a clear ending to this story, it is not in a courtroom dramatic moment where I triumph and walk off into warm light. My life is messier and, therefore, truer. The ending is the slow, practical unstuffing of a life: cleaning out the books, choosing the people I will spend time with, and hearing my own voice when I want to speak instead of holding my breath for permission.

I sometimes think of that dinner because nights have a way of returning you to the shape of decisive acts. I remember the clink of silver and the way laughter had once been a weapon. I remember the way I smiled and walked out, a passage close to myth in my head because it was a small but irrevocable threshold: a human being refusing to be small because other people are comfortable with their size.

Two days later the house collapsed in the public eye. Two years later, the house has learned to be quieter. I have a blue house, lavender, a table full of friends, and the occasional unhelpful call from relatives who expect things to be the same. Those things are small. They are enough.

When my father finally said, weeks after the scandal began, “You were right to protect the assets,” it was not an apology shaped for the headlines. It was a man who had come to terms with the idea that his life’s fruit was not cultivated out of endless privilege but out of hands he once considered merely useful. What he could give me then was only his truth, and that was, in the end, the beginning of something more valuable than money: the chance to build a life where my worth is not conditional.

If you ever find yourself standing at the head of a polished table, and someone announces you are unworthy, remember that the world is not only composed of people who laugh loudly in luxurious rooms. There are people who keep records, who build vaults, who hold long memories of every ledger line. Sometimes the quietest person at the table is the one who keeps the keys. Give them their choice: to lock the doors and walk away, or to keep them open and teach a better way of tending the house.

I chose freedom. The inheritance they tried to take from me turned out to be the thing I had always carried: the ability to decide what I would protect and what I would let go. The house lost its glow. The lavender in my yard kept blooming. The end—if it must be named—was a small, clear thing: I drank my wine, smiled, and left. Then I built a life that did not require anyone’s permission to be beautiful.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

MOM GLOWED, “YOUR SISTER’S WEDDING WAS MAGICAL! WHEN WILL YOU FINALLY HAVE YOURS?” I JUST SMILED. CH2

My Mom glowed, “Your sister’s wedding was magical! When will you finally have yours?” I just smiled and said, “It…

My boyfriend took off my hearing aid to propose. They didn’t know my ears healed last week… CH2

My boyfriend took off my hearing aid to propose. They didn’t know my ears healed last week… PART 1…

Parents Said My Headaches Were ‘Attention Seeking ‘ The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden. CH2

Parents Said My Headaches Were “Attention Seeking.” The Brain Scan Showed What They’d Hidden PART 1 The migraines started…

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything. CH2

My Dad Slapped Me For ‘Disrespecting’ His New Wife The Hidden Camera Changed Everything Part One The slap arrived with…

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing. CH2

My Stepdad Dragged Me Out of Bed By My Hair While Mom Filmed Him Laughing Part One Stop. Stop, stop—you’re…

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career. CH2

My Mother Banned Me From Family Gatherings So My Pregnant Sister Wouldn’t Feel Jealous of My Career Part One They…

End of content

No more pages to load