My Parents Humiliated My Son… But Then They Paid The Price

Part One

The moment my son lifted the lid and found nothing inside, the room seemed to tilt.

Ethan’s small fingers stayed hooked over the edge of the glossy box as if he could tug a gift out of air by believing hard enough. The chandelier light skittered over the paper, over his cheeks, over the places where awe—a heartbeat old—had already drained away. Confusion bloomed. Then the flush of embarrassment. Then the terrible, learned stillness of a six-year-old trying not to cry.

My mother laughed.

It was a light, well-trained sound—the same laugh she used at charity luncheons when people said something mildly improper. Only this time it broke against me like ice water. “Oh, don’t look at me like that, Lauren,” she said, adjusting the strand of pearls against her cashmere, calm as a lifeguard watching a drowning from the deck. “He doesn’t need anything. Besides… it builds character.”

Across from me, my father swirled Scotch and studied its surface as if answers pooled in amber. My brothers and sister—Henry, Charlotte, and Olivia—shifted in their chairs, eyes darting, mouths half open and then closed again. Beneath the music in the grand piano, the house creaked with the weight of performed perfection.

I felt my nails press crescents into my palm. The urge to cross the room and snap that laugh in half was a pulse in my throat. But violence is easy. The hard thing is control.

I stood carefully, chair legs whispering against polished wood. I lifted my son and pressed a kiss into his hair. “Let’s go, sweetheart,” I said, and when I turned toward my mother I smiled—not the soft smile she taught her daughters to wear, but the one with edges. “Thank you, Mother.”

Daniel rose beside me without a word, his anger a steady heat at my shoulder. No one tried to stop us. No one knew how. The grand piano kept playing as we crossed the foyer, that Noel lilting ridiculous and bright. Behind us: the twelve-foot tree, the crystal, the elegant mop of grandchildren unwrapping devices and designer gear. In my arms: a boy who had just learned the speed at which love can be measured in boxes.

Outside, the night was clean and cold and honest. Snow tucked down onto the edges of the steps like a napkin under a place setting. I settled Ethan into his booster, buckled him with shaking hands. He kept his face turned up toward me.

“Did I do something wrong?” he whispered—the question small enough to shatter a cathedral window.

“No,” I said, though the word cut my throat to make room for itself. “You did nothing wrong.”

Daniel shut his door with a decisive click. We pulled away from the Whitmore estate—the house I grew up in, the house that had taught me the shapes of rooms and the shapes of silence. I watched it shrink in the rearview mirror: grand, lit, and empty as a gilded promise.

The vow I made in our driveway didn’t take up space. It didn’t need to. I said it once, to the snow and the porch light and the skin above my son’s crown: You don’t get to do this for free.

Three days earlier, the world had still felt soft around the edges.

Snow drifted, halfhearted and quiet, past the living room windows of our plain colonial. The tree in the corner wore our history—felt stars Ethan had cut with his small, careful hands; the crocheted angel my grandmother made the year I was born; the paper chain that seemed ridiculous and then suddenly necessary. The house smelled like cinnamon and pine and the kind of cocoa you make with both milk and patience.

At the coffee table, Ethan tied ribbon around a small box. He pulled the knot tight, squinted, then looked up. “Do you think Grandma and Grandpa will like it?” he asked, earnest as dawn.

I glanced at the ornament he’d painted at school—uneven stars, a crooked date, his name looping across the glass in his teacher’s careful print—and swallowed the truth for the thousandth time. “They’ll love it,” I said, as mothers have lied for centuries to protect small joy.

He looked past me to the window where the first soft sludge of plows whispered the street awake. “Do we have to go?” The question had been coming all month, delivered in different wrappers—pretending to be a joke, to be curiosity, to be a plea. Every time it landed, it left a mark.

I knelt and cupped his cheeks. “It’s Christmas,” I said, light because he deserved light. “We’ll be together. Whatever happens, Dad and I will be there.”

From the doorway, Daniel cleared his throat. His Navy sweater made him look gentler than he felt. “We don’t have to go,” he said, careful. “We don’t have to do any of this if it hurts him.”

“We both know,” I said, already tired of being a daughter in my own mouth, “how they are if we don’t appear when summoned. They don’t punish us. They punish by pretending to forget Ethan exists.”

Daniel’s jaw ticked. “Then we teach them we know how to forget right back.”

“Not yet,” I said—and watched the word land like a weight on a scale. “Later.”

The Whitmore estate in December could’ve been the cover of a magazine if the photographer knew how to crop out malice. The Victorian towered, all white stone and lit windows, its iron gate gilt with a tasteful, expensive wreath. Inside, Brahms floated over crystal and a curated mountain under a twelve-foot fir. My mother wore winter white; my father wore indifference.

“Jenny! You finally made it,” my mother called, stage voice pitched at the exact frequency to be heard across marble. We stopped in the foyer. She brushed her lips at the air near my cheek; her perfume was the exact expensive kind that smells like nothing. She didn’t look at Daniel. When my father boomed “Patricia!” from the next room, Ethan’s hand tightened around mine. My father will never call me by the name my husband speaks. He will never call my husband anything.

In the living room, the staircase was a runway for grandchildren who had learned to show gratitude the way a Whitmore shows everything—brilliantly lit, indefinitely. Olivia’s twins held up a gaming console like a trophy. Charlotte’s daughter swiped her finger across a new tablet: “It recognizes my face!” Henry’s son shouted statistics about hand-stitched leather and leagues. I wanted to say, quietly, That leather doesn’t know your name. Instead, I put Ethan between us and the wall.

When he tried to tell my father about his shoebox diorama of the solar system—“I used foil for the moons!”—my mother looked at her watch and said, “Let’s save children’s chatter for after dinner,” and pivoted back to market talk with Henry as if Ethan’s voice were Thanksgiving leftovers—fine if warmed properly, best ignored if you care about cutlery.

Dinner was an exercise in pretending we were not performing. The china was heavy with inheritance. The wine was older than my marriage. My mother steered conversation like she steered everything—toward herself, away from pain. When the crème brûlée crusts clicked like tiny hammers, staff began bringing the piles of prettiness into the tree room.

My mother handed boxes with her name printed on tags the size of credit cards. She made eye contact. She said full names in public. She did grace the way other people do yoga. And when it was Ethan’s turn, she smiled at him and placed a small square in his hands like she had wrapped a heart and knew it.

He peeled paper with ritual care. He lifted the lid as if it might bite.

It did. Inside: nothing. Not tissue, not a note, not a coin taped mischievously to the corner. Just air and a long fall.

And my mother—my mother laughed.

The silence after was its own kind of music. You could hear the fire shift. You could hear a boy unlearn joy in a single breath.

“Oh, don’t look so disappointed,” my mother crooned when she realized no one else would fill it for her. “He doesn’t need anything, does he? It builds character.”

If there had been a camera, I could have removed the reel of my life as a daughter and burned it in the grate. But there wasn’t. There was only a boy I promised to protect and a man beside me who had that promise between his molars like leather he would chew through his jaw if he had to.

I stood instead. People who live on cliffs don’t jump. They choose their way down. I kissed my son, turned to my mother, and offered a thank-you she couldn’t place but would learn to recognize soon enough.

We left. The piano kept playing. Behind us, Whitmore guests put their hands over their hearts and said, Well.

You don’t make a decision like we did and sleep easily. I lay awake that night and listened to the house breathe and felt a storm wind itself around my heart like a terrible ribbon. In the morning, Ethan trudged into the kitchen with yesterday still on his face.

“Does Santa still come to Grandma and Grandpa’s?” he asked the counter.

“Santa goes where you are,” Daniel said, ruffling his hair with gentleness that made my throat hurt. “Always.”

Before I could say anything else, my phone vibrated across the island. Olivia. I stared at her name until the letters blurred.

“This is unacceptable,” she said without greeting when I answered. “I should have said something. I should—”

“You didn’t,” I snapped, surprising both of us, “and neither did Charlotte or Henry. You sat while a six-year-old got taught the price of not being a Whitmore who spends right.”

Silence. Then, quietly, “You’re right.”

I almost dropped the phone. We were raised on apologies as currency—exchanged for a fast fix, not a changed behavior. We were not raised on the kind that is plain. “We’re done,” she continued, voice gaining edges. “We talked this morning. Charlotte, Henry, me. We’ve had enough.”

“With what?”

“The maintenance,” she said briskly, and I could hear her already making lists. Olivia organizes like gladiators fight. “The money, the access, the invisibility we’ve all agreed to wear so they don’t have to see what they do. It ends today.”

My mind flashed through the apparatus we’d kept humming out of habit and fear. Olivia’s account that covered concierge transport for every specialist appointment. Charlotte’s legal triage every time my father signed something without reading it. Henry’s double-checks on their investments that had kept them afloat through three bad decisions and one quiet crash. Me—paying contractors to keep the house smooth at the seams and the club autopay on a card because it was easier than hearing my mother complain about the indignity of checks.

“Pull it,” I said, and felt something inside me click into place like a key in a lock that had always been meant for my hand. “Pull it all.”

We made calls in a rhythm that felt like prayer.

Charlotte to the maintenance firm: “We won’t be renewing. The terms are immediate.” Olivia to the hospital’s VIP transport coordinator: “I won’t be responsible for any future charges.” Henry to the financial advisors: “Pull my parents’ discretionary. Freeze what you can freeze until we can sort what’s theirs and what was ours pegged to them.” Me to the country club: “Cancel the autopay. If you need to send a bill, send it to the estate. But you might want to call the board chair first.”

It took less than twenty minutes to end twenty years.

By nightfall, the edges of their life were already fraying. A declined card at the club turned into a small story passed quietly in a dining room that lives for audibles. A “so sorry, the doctor is booked for months” replaced my mother’s customary “We’ll see you at two.” The lawn crew texted that they were short this week and could they push them to Friday? By Friday, nothing with a motor came through the gate unless my mother opened it from inside in boots.

The most painful thing wasn’t the phone calls that went unanswered. It was the ones that did. Their old crowd has a gift for polite cruelty. “Oh, darling,” a woman with pearls threaded down to her sternum cooed into my mother’s voicemail, “we’re in Palm Beach that weekend. Kiss kiss.” My mother had never been the one kissed. She had always been the one looked at.

The HVAC failed during a cold snap. She sat in her peacoat on a brocade sofa and called me and hung up before the line connected. A week later, the estate looked like the kind of house people drive past and say, Shame what time does, isn’t it? Time, and the collapse of a scaffolding we had built with our backs.

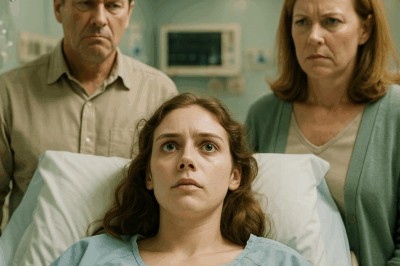

Two weeks after Christmas, they came to our door.

I will say this for my parents: they did not send a driver.

They stood on our stoop where trick-or-treaters had stood and Jehovah’s Witnesses and a boy who wanted to shovel snow for five dollars less than the going rate. My mother’s hair was a little wrong. My father’s coat looked tired. For the first time in—ever—they looked like people who had been told no often enough that they expected to hear it again.

“Lauren,” my father said, and his voice was not the one he used on boards and waiters and sons-in-law. “We need to talk.”

I did not open the door wide. Power is a threshold. I let them into my kitchen like any ordinary parents and watched them look at our ordinary countertops as if they might crack the first eggshell honesty anyone had ever handed them.

“We’ve had—” my father began, then caught himself. “We have had a difficult few weeks.”

“Challenges,” my mother offered, and I had to put my hands on the counter to keep from applauding the restraint it took for her not to say the word misunderstanding.

“That must be terrible,” I said with a smile that didn’t reach my eyes. “To realize how many people liked you for what you offered to pay for.”

They both flinched. Good. My father straightened and for a heartbeat still looked like the man who could sell you anything, including a story where you’re the villain and he’s the rescue. “We were wrong,” he said, very quietly. “We forgot what mattered. We let pride turn into… cruelty.”

He looked at Ethan because he had the sense to look at the wound. My mother wrapped her coat tighter because she had nothing else to hold on to.

And then: the soft, sandpapery voice I would have set the world on fire to protect.

“Grandma?”

Ethan stood in the doorway of the hall in socks and bed hair, life still creasing his cheek where it had pressed into the pillow. He looked at me first, because children measure their words with the tape of safety. I nodded, and he walked into the room with the strange dignity of the recently injured.

“Why don’t you like me?” he asked, and in that one terrible, perfect question he saved us all the courtesy of pretending our pain was academic.

My mother sank a fraction. Fine cracks appeared beneath her foundation where the cold got in. She opened her mouth and nothing came. When she found a voice, it was a voice I had never heard. “I…” She reached for the back of a chair and held it like a life preserver. “I deserve it if you don’t forgive me.”

Ethan considered this and then did the only thing in the room that wasn’t theater. He walked to the bench, picked up his red sweater, and held it up to her with a seriousness that made my teeth ache. “You can borrow my warm,” he said.

It wasn’t absolution. It was the smallest loan.

My mother took the sweater as if it were holy. My father put his hand on her shoulder, and it was not a performance. He turned to me. “Can we begin again?” he asked. Ten thousand would-you-kindlys lived in that question.

“You can try,” I said. “On my terms.”

The conditions were not dramatic. That’s how you know they’re real. No more public corrections disguised as jokes. No more loving you by controlling you. No more counting our love in invoices. No more cutting my son down to build your story.

“And if you want a relationship with us,” I added, “you work at it. Not with money. With casseroles and showing up when the call is boring. With remembering how old your grandson is without having to ask the housekeeper. You earn us the way the rest of the world earns each other.”

My mother opened her mouth to tell me how things work. My father put two fingers on her wrist and she closed it. He nodded. “We understand.”

I would have forgiven them, then, if forgiveness worked like a switch. It doesn’t. It’s a practice, not a performance. And they took it up—surprisingly, haltingly, and then with a kind of relief.

The recession for the rich that happens when you lose your children’s money is quiet. There is no siren. There is only the interior of your own house and no one to open your mail for you. My parents learned the right size of pill bottles when you’re not a VIP. They learned you can mow a lawn badly and nothing terrible happens. They learned how to talk to a contractor who does not owe you his loyalty and can recommend you work with someone else. They learned you can sit in a book club and say you don’t understand the metaphor and the women will nod and pour you more coffee. They learned that the world did not end when they wore last season’s coat into town, and that people are kinder at the farmer’s market than at the club.

My father took a volunteer bookkeeping role at the senior center. “Someone needs to reconcile the accounts,” he told me one Saturday like he had discovered purpose and wanted to return it for a smaller size because he finally realized it fits. “They keep paying invoices twice.” He brought home stories about the men who taught him cribbage and the woman who made him cry with a song from 1957.

My mother joined a book club and did not host anything. The first time she said the sentence “I didn’t understand that chapter,” she called me afterward with a laugh that made her sound like a girl. “They told me they didn’t either,” she said, shocked. “And then we talked about our kids without saying their names like we’re going to monetize them.”

Every Saturday, they came to our house with produce and an apology hidden in it. They sat at our table and helped with math homework and realized a first-grader’s logic rules always, always beat calculus in a kitchen. They clapped at little league and didn’t correct anyone’s stance. When Ethan brushed dirt over their hands in the garden and told them that soil is like cake but for plants, my mother laughed so hard she knocked over the watering can, splashed her boots, and gasped at the cold like she was alive.

Once, washing dishes with me after, she stood with her hands in suds long enough that steam turned her cheeks pink. “I knew how to be important,” she said without looking up. “I did not know how to be needed. I’ve been… learning.”

“You can keep learning,” I said. “But if you hurt him again, you don’t get another lesson. You get the door.”

She nodded, and for once the gesture didn’t feel like a surrender. It felt like an agreement.

By spring, the Whitmore estate was no longer a place anyone bragged about visiting. The hedges grew weird. The fountain coughed instead of sang. The neighbors invented stories gently over fences, the way people do when they don’t know and are too polite to ask. My parents started spending most afternoons at our place anyway because “the light’s better here,” my father said with a straight face the day he showed up with lemon bars his book club friend had made and said were “a revelation.” I did not remind him he used that word for Bordeaux once.

On a soft evening, I stood at the sink and watched the three of them in the yard. Ethan showed my parents how to loosen soil carefully so you “don’t break the roots’ feelings.” He handed my mother a trowel, serious as a surgeon, and my father held the hose like it was a new instrument he was being allowed to play gently. Ethan’s laugh lifted and my mother’s followed—unguarded, inelegant, much better than any sound she had performed before. Daniel slipped an arm around my waist.

“Did you ever think we’d get here?” he asked.

“No,” I said, honest. “But I think it’s enough.”

He kissed my temple and went back to the stove. Outside, my mother tried to push her hair behind her ear with dirty fingers and left a smudge. She did not flinch. She just smiled at my son like he had invented the sun.

That Christmas, Ethan handed my mother a box wrapped in paper he’d chosen himself. He watched her open it—the way children always watch, learning carefully what love looks like. Inside: a handmade ornament, blue paint, wonky stars, his name written in letters that had practiced all week.

My mother found the ornament, and then she found her voice. “It’s perfect,” she said—by which she meant, I failed you. I am trying. I am learning how to get this right. Thank you for letting me. She hung it too low on the tree on purpose because that’s where little hands can touch.

After dinner, when the house was quiet and the dishwasher hummed and the last of the snow outside turned blue under the porch light, I took down the empty box from our top shelf—the one that used to hold napkin rings and now held a story. I set it on the table between us. My mother looked at it, and then at me.

“I don’t know how to say I’m sorry enough,” she said plainly. “So I’ll just keep coming until my showing up is bigger than my mistake.”

“That’s the only way it works,” I said. “And it won’t save you from consequences. It just gets you invited back for cake.”

She smiled the kind of smile that has nothing to do with being seen and everything to do with seeing. She reached into her purse and took out a folded piece of plain paper. On it: a schedule scribbled in her neat hand—Tuesdays: pick up from school. Thursdays: homework with Nana. Saturdays: farmer’s market, no country club.

“I’m learning,” she said, as if it were a verb.

“Good,” I said. “So is he.”

Ethan padded in from the hall in pajamas and socks, hair sticking up into ideas. He climbed into my lap and gave my mother a solemn nod. “Grandma,” he said, serious, “if you forget how to be nice again, I can remind you.” He held up the red sweater. “And if you’re cold, you can borrow this again.”

She laughed, and the sound put something back inside my chest I hadn’t known was missing until it returned. Later, when the lights were off and the house existed only by the sound of people sleeping inside it, I stood at the window and thought about boxes.

There was the box my mother had handed my child: empty, cruel, teaching a terrible lesson about worth. There was the box we built around our pain and set on a shelf where we could see it and remember that we would not store ourselves in it anymore. And there was the box on the table now: not empty, not full of gold, just the right size to hold a paper schedule that meant “We will be here, on purpose, at these times, because you matter to us.”

They had paid a price, my parents—status and ease and two months of learning to call contractors by first names. But the real cost was one only they could decide to pay: humility. They had done it badly and then better until it began to look like grace.

Ethan fell asleep that night with the red sweater folded on his desk like a flag. I checked him twice and then once more, because love doesn’t cure fear so much as teach it to nap. In our bed, Daniel slid his hand into mine under the covers and we lay there in the dark counting breaths like we used to when contractions came.

On the kitchen counter, the empty box—that box—sat open and silent. I lifted its lid once more. I thought of my mother’s laugh and my son’s question, of Olivia’s rare admission and Henry’s quiet willingness to do the unglamorous work of love, of Charlotte’s legalese turned into boundaries and my father’s volunteer ledger with its columns of debits and credits, and of what I had put inside that box now.

It wasn’t silver or apology or money. It was the clear-eyed knowledge that a family will become whatever you allow it to become—and that you can choose to stop allowing.

I closed the lid gently, not to hide anything, but to keep it safe for the next time I needed to remember: when you humiliate a child, you destroy a family. And when a mother finally refuses to accept that, she builds a better one with whatever she has left.

Part Two

The winter after the empty box, the Whitmore name thawed the way ice does—not with drama, but with sound, with small shards giving way underfoot. The estate did not collapse. Houses rarely do. They simply confess more of themselves when there’s no staff to hide the secrets.

When the heat went out during the first real cold snap, my parents didn’t call me. Margaret told me. “She sat at urgent care with a scarf on,” my mother said later, folding her hands around a mug at my kitchen table like she wished it were warmer than it was. “The receptionist called her ‘ma’am’ and meant it as if it were a kindness, not a title. It felt… new.”

They learned the economy of kindness that is not purchased. A woman at my mother’s book club took her to dial-a-ride. My father’s bridge partner told him where to buy oil filters on sale. The woman at the pharmacy taught my mother that if you bring ginger cookies you can sit in the chairs that face the window.

When Olivia cut off the medical transport, my mother stopped talking to her for three days. On the fourth, she called and asked how exactly to enroll in a plan that didn’t make her feel like a number. Olivia sent a list and put her on hold when Ethan’s cousin tried to show her a Minecraft world. My mother listened to the hold music and realized she had started to recognize songs on the radio that teenagers like. She wondered if that meant she was changing, and then decided not to think about it too hard and to just keep going.

At the senior center where my father reconciled accounts for free, he learned the names of thirteen people’s grandchildren and how to make coffee strong enough for a ninety-three-year-old to say, “Now that is coffee.” When he told me that story, his voice didn’t sound like the voice he used to give toasts. It sounded like the voice he used when he carried me to bed after I fell asleep in the car when I was seven—the one he probably thought I couldn’t remember.

On Saturdays, my parents showed up at our door with produce from markets I suspect my mother once pretended were quaint. They learned to like the kind of apples that bruise if you look at them wrong and taste like you lived right. They sat in the bleachers at little league and kept score with a pencil and said things like, “Good eye!” to other people’s children because you don’t get to reclaim love by keeping it to yourself.

We did not forgive everything at once. We were not stupid. Daniel reminded my father, gently but with a backbone, that he doesn’t get to comment on my married name anymore or the way we spend Sunday mornings. My mother put a gift on the table one night—an envelope with far too much money in it meant for a vacation because we looked “tired”—and I slid it back and said, “No.” She flinched like I’d struck her. “If you want to give us something,” I said, “you can come at six next Friday with takeout and play Monopoly with your grandson while Daniel and I go eat alone in a restaurant and talk like we used to.”

They came at five-thirty and brought pizza that cost too much and was worth exactly what my mother paid for it because, for the first time in her life, she didn’t tip to be seen. She tipped because the boy who brought it looked like the boy who mowed our lawn and she wanted him to go home with hands that felt respected.

Over time, the muscles of our family remembered how to hold us. It is not that the hurt went away; scar tissue will always be there if you know where to press. It is that we built new muscle over it. It is that when pain came knocking, it no longer found the door with the loose hinge. It found a door that fits.

Easter, then summer, then dispatches from the senior center about someone’s birthday cake that needed “less frosting next time.” Daniel restored an old lawn chair and my father sat in it and said, wonderingly, “This is very comfortable,” like a man who had never been taught to rest his own weight in something simple.

On a hot evening in July, my mother came into the kitchen and asked where we kept “the good scissors,” and I said, “In the drawer we agreed would be for scissors,” and she laughed in a way that did not have steel in it and reached for the right drawer without telling me I kept house differently than she would. She cut twine and tied up tomato plants with the competence of someone whose nails still managed to be perfect afterward and who no longer cared about it as much.

“Can I tell you something?” she asked that same night, sitting on our back steps while Ethan tried to coax moths into a jar and then let them go because he remembered that jars are prisons no matter how pretty. She didn’t wait for permission. “I didn’t know I would feel grief for a thing I never actually had,” she said. “I didn’t have the right to what I thought I’d lost. But I grieved anyway. And then… you gave me chores, and the grief got quieter.”

“You gave yourself chores,” I said.

She looked at me and we both smiled, because you don’t unlearn everything at once. “Fine,” she conceded. “But you let me have them.”

That was the difference. They had lived their entire lives holding the remote and choosing the channel and then pretending the television switched itself. We took the batteries out. They learned to read. It was work. It was worth it.

The lesson started with an empty box, but it didn’t end with a teardown. If it had, this story would be boring and the internet wouldn’t know what to do with us. The price my parents paid was not the kind you can see on a spreadsheet. It was pride, traded in increments for particular forms of love: for the sound of a boy’s laugh in a backyard, for the ache in your thighs after you kneel to pull weeds for longer than you’d like, for the knowledge that you are not the main character in the lives of the people you raised and that this is not a tragedy.

Our last Christmas of this story (because there will be more and none of them will be perfect) came with less snow and more people in the kitchen. Olivia brought stuffing that was too wet and Henry made a prime rib he’d been practicing since September and Charlotte lit candles like prayer and my mother hung a paper snowflake Ethan cut where everyone could see it and then corrected herself and moved it lower, pride melting into practice. My father took his place at the table where you can hear other people better and told a joke that got the timing wrong and we all laughed anyway, kindly.

There were presents under the tree, because six-year-olds still count them even when their mothers tell them not to. When it was Ethan’s turn, my mother handed him a box the size of a shoe box and looked me in the eyes in a way that asked permission and promised… not everything, but enough.

Inside: a wooden box with compartments. In the compartments: packets of seeds. On the inside of the lid: a schedule and a child’s handwriting in pencil that was not my son’s—my mother’s letters carefully imitating the wobble of love so he wouldn’t feel outclassed by a grandmother who has always had better penmanship: Peas in March, carrots in April, sunflowers when it’s warm. Love, Nana.

Ethan looked up at her, and the mercy in his face made me want to kneel and kiss the ground. “We can plant them tomorrow,” he said, grave. “But you have to wear boots.”

“I will,” she said. “I will wear boots.”

Daniel held my hand under the table and squeezed once. I squeezed back.

Later, after the dishes and the second round of cookies and the small ache you get in your face when you’ve been careful with your expressions all day, I took the old empty box out of the hall closet—the one I had not thrown away because discarded symbols tend to return like cats. I set it on the table and opened it one last time. It held air like it holds everything. I lifted it, shook out the quiet it had taught me, and carried it to the recycling bin.

When I came back inside, my mother was helping Ethan put his boots out by the back door. My father was at the sink drying a pan with a towel and a concentration that suggested the pan was a newborn. In the corner, our small tree winked at me with the intimate light of things that know your life from the inside.

People talk about paying the price as if it’s a one-time transaction. It isn’t. It’s a subscription you keep renewing until your life lines up with your values. My parents had humiliated my son to maintain a story about who they were. When the bill came due, they could have defaulted. They didn’t. They paid in humility and habit and showing up, and then they kept paying.

It didn’t make what they did right. It made what came next possible.

I kissed my son’s head, stood up, and turned off the porch light. Snow started again, thin and stubborn. In the morning, if the earth wasn’t too hard, we would plant something. If it was, we would make hot chocolate and draw plans. Both things grow people. Both things build families.

The difference, I learned, is that one kind of box is a trick and the other kind is a garden bed. This year, the box was full.

END!

News

At my wedding, my mother-in-law declared, “the child she’s carrying belongs to another man” CH2

At my wedding, my mother-in-law declared, “the child she’s carrying belongs to another man” Part One I can tell…

I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” ch2

I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” — So I… …

After I Caught My Husband With His Mistress, My Mother-in-Law Threw Me Out of the House. ch2

After I Caught My Husband With His Mistress, My Mother-in-Law Threw Me Out of the House—But… I grew up in…

My Sister’s Prank Left Me Paralyzed—Parents Called Me Dramatic. The MRI Results Made Them Criminals. CH2

My Sister’s Prank Left Me Paralyzed—Parents Called Me Dramatic. The MRI Results Made Them Criminals Part One My name…

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… CH2

My Parents Bragged, “Your Sister Finally Got the Perfect House and Car!” I Just Sat There… Part One I…

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited me Over Just to Tell me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her. CH2

At Family Dinner, My Sister Invited Me Over Just to Tell Me That My Inheritance now Belongs to Her …

End of content

No more pages to load