My Parents Forced Me To Give My Penthouse To My Sister. When I Refused — Dad Slapped Me, So I…

Part One

My name is Jenna Brooks, and at thirty-two I thought I had finally outrun the version of myself my family loved to hold up like a cautionary tale. I was the one who left early dinners to take calls with India, stayed up late debugging sideways code, turned a fledgling platform into a product Fortune profiled. I ate ramen long after I could afford better, and when the stock options matured and the penthouse keys landed in my palm, I didn’t think, I did this in spite of them. I thought, I did this, period.

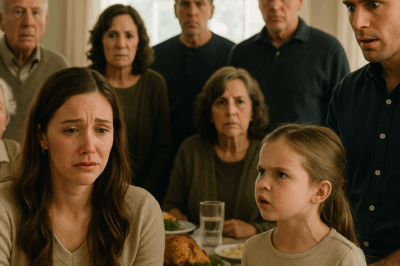

The night of my older sister’s thirty-fifth, Atlanta threw on the kind of humidity that makes silk cling and men regret jackets. My parents’ condo—towering glass above Buckhead—glowed like a lantern. The valet stand was a procession of imported badgework. Inside, marble floors, crystal chandeliers, a quartet arranged themselves in front of a wall of windows swallowing an orange-blue skyline. I’d chipped in for the chef and the wine because that’s what you do when your mother says, “We don’t want to embarrass ourselves in front of the Larsons,” and because no matter who else I had become, there was still a piece of me that wanted to belong at their table without flinching.

My mother’s voice carried from the dessert table, equal parts stage whisper and assessment. “The lemon glaze needs to be glossier. Where are the berries I told you to sprinkle?” She looked right past the woman who had paid for half of it. My father worked the room with the confidence of a man who introduces himself to people who already know his name. Ethan, my sister Tara’s fiancé, nodded and said the right sentences in the right order. Tara floated in a designer dress my mother called “timeless” and wore like a clock that only goes forward.

“You must be so proud of your sister,” Mrs. Larson said, pressing fingers wrapped in diamonds to the stem of her flute, the question disguised as praise.

“I’m proud of a lot of things,” I said, and wondered whether this woman had ever once asked someone, “You must be proud of yourself.”

The quartet changed direction into something Vivaldi and my father raised a glass. I braced for a story about Tara’s “vibrant spirit,” a phrase he had used so often it had become a cologne. He delivered that paragraph first, the one about her light, her grace, the way she brightened rooms without suggesting she ever flipped a switch. And then, microphone in hand, smile as fixed as his part, he pivoted.

“Tonight,” he said, “we celebrate family as it ought to be. We look after each other. We share. We lift. And I am proud to announce that our generous daughter Jenna is gifting her penthouse to her sister to help Tara and Ethan begin their life together.”

The room did that thing where silence decides to show off. Claps that had started faithfully faltered mid-air. A few hands kept going the way car alarms do after the thief has fled. Heads turned toward me as if I were a surprise cake that had just been wheeled in. Tara gasped, pressing her palm to her sternum with the rehearsed muscle memory of someone who has cried beautifully in a mirror. In the split second between performance and control, I saw the flicker—the pleased wrinkle at the corner of her eye—and I knew this speech had not sprung fully formed from my father’s mouth.

“It’s only fair,” he said into the stunned quiet, turning his mask in my direction and speaking like a megaphone. “Tara’s been… searching. Jenna has been blessed. Family means sharing blessings.”

Blessings. As if the penthouse had rained down and landed wilted on my doorstep. As if I had not tuned my life to a single stubborn frequency and moved chairs in the symphony until they played the notes I wrote. I set my glass down so gently you could have mistaken the sound for punctuality and stepped forward.

“No.”

A word that small shouldn’t carry the weight it did. It slid across the marble and stopped in front of every shoe. Aunt Nancy’s, “Don’t be selfish, dear,” hung in the air like perfume you don’t remember putting on. My mother’s mouth pinched into the kind of line that makes you think of erasers. My father’s face did the thing where thunderclouds decide they’re also lightning.

“What did you say?” he asked, his voice sharpening on the edges. The quartet looked at their sheet music as if the answer might be there.

“I said no,” I repeated. “I worked for that home. I put the hours in when everyone else went somewhere. No one has the right to offer it like a party favor.”

“Jenna,” my mother said, her voice knife-soft, “you’re embarrassing us.”

“‘Us’,” I said, “is doing a lot of work in that sentence.”

“This family has carried you,” my father said, stepping forward, his hand tightening around the microphone, knuckles white.

“No,” I replied, surprised at the calm in my own mouth. “I’ve carried me. I’ve carried you through a cancer bout, Mom’s two conferences, a down payment you needed to borrow for Tara’s last apartment because the landlord suddenly discovered her charm was not legal tender. I have paid for tutors and plumbers and therapists none of you had the courage to call for yourselves. I have nothing to apologize for.”

And then it happened. Not slow, not cinematic. It happened like weather. His hand cut the space between us and landed on my cheek with a sound that made someone gasp out loud like they had been touched. Heat bloomed under bone. The pearl my grandmother had given me flew, bounced once, spun under the table where Aunt Nancy clutched her necklace as if to verify its quality. For a heartbeat, you could hear electricity and breathing and the furious little click of someone’s fingernail tapping a phone screen to go live.

My mother’s voice found its footing before his did. “Apologize to your father,” she snapped, and in the tin between us I could hear all the ways this family had always told the wrong people to say sorry.

Instead, I bent, picked up my dignity in the shape of a pearl, and put it in my pocket. I looked at Tara. “Happy birthday,” I said, and walked toward the door. A path formed because disgust knows how to do the right thing when it’s finally forced to. In the hall, the cold air of the AC found the heat in my cheek and made a fog of it. I dialed a name without thinking: Kayla.

“Tell me where you are,” my best friend said when I said, “He hit me.”

I gave her an address for the hallway. “Call your grandmother,” she said. “Now.”

Grandma Margaret did not care for elevators. The last time she had consented to one, she’d said, “The last person who tried to carry me upward uninvited is buried in a poem,” and we did not question her. So when the penthouse doors opened thirty minutes later and she strode in with her cane like the prologue to a reckoning, I did not think, Where did she park? I thought, Oh, we are finally going to tell the truth in this family out loud.

At eighty, she had a spine that could cut fruit and a mouth that had never learned compromise as a first language. She crossed the marble that still held the faint ghost of my shoe steps and stopped where my father stood with the microphone that now seemed indecent.

“Daniel,” she said, using the name no one dared and pronouncing all its angles. “Explain to me why the hand I taught you to hold your daughter with became a fist.”

The room waited, because no one interrupts a queen. He opened his mouth and looked like he might say, “You don’t understand.” She lifted her hand and all his explanations fell out of it like coins back into a purse.

“You have five minutes to find your daughter’s earring,” she said, as if this were a parable and we were about to disappoint God. “If you cannot locate it, I will draw conclusions.”

People went to their knees like a piety they hadn’t practiced in years. My mother fluttered at the edges of things. Tara sobbed in a voice tuned to be flattering, not true. Aunt Nancy’s mouth formed her favorite word: outrageous. I stood at the back and watched my grandmother take aim at the version of our family she had been pretending to tolerate.

“Jenna is the only one in this room,” she said, “who has never asked me for money. She is the only one who has ever called to tell me a thing that was hard and not because she needed a check attached to it.”

“Mother,” my father said, outrage making him sloppy, “this is not—”

“This is precisely what it is,” she replied, and tapped her cane on the floor three times to make sure everyone remembered how wood feels when something important is about to be said. “I am rewriting my will.”

Silence has a way of turning into gravity when someone says the thing that changes all the tables in the house. “My estate, my house, my accounts, all of it,” she continued, “will go to Jenna.” She let the words find the ears that had spent years not hearing. “You”—she included my mother and my sister in a single withering glance—“have trained yourselves into weakness. You have mistaken a daughter’s success as something you could pick up and put down as needed. You are at a loss because she has finally discovered the word no, and you do not know how to move around it without tripping.”

Phones lifted and pointed. The string quartet did not resume. Someone actually whispered, “Put the ring away, Ethan,” which would have made me laugh if laughter had not been something I had stopped keeping in my pocket around this family years ago.

The five minutes expired. The pearl remained in my pocket. Grandma did not ask where it was. She knew. She looked at me, and I saw my mother at twenty-five in the way she held her jaw. “You did right,” she told me in a voice she had never used in a room with my father, and I leaned against the doorframe because my body needed something to absorb what that sentence did.

That night the video of my father’s hand traveled Atlanta like gossip finally having something useful to do. By morning, it had spilled over into the rivers where the city stays polite. People shared and added sentences about daughters and ownership and the ethics of expecting your children’s success to be communal property while their dignity remains negotiable. Tara’s fiancé’s mother called mine the next day and said words like “reputational risk” into the phone because sometimes life insists on being on the nose.

My parents came to my door one evening with faces that had practiced contrition and had not rehearsed it nearly enough. My mother carried a Tupperware of stew that tasted like apologies and onions. “We made a mistake,” she said. “We were trying to help your sister. The pressure—”

“The pressure to keep doing the wrong thing in public,” I said, and took the container because I am capable of receiving a kindness from the hand that delivered harm.

“We’re family,” my father said. “We can fix this.”

“You’re not wrong,” I replied. “We are family. And the only way families get better is if they tell the truth about where they went wrong and sit in that room without opening the windows until they understand the smell.”

They did not understand. Most people do not. I closed the door softly. Kayla arrived shortly with a bottle of wine and her “You did it” face, which looks like love wearing sneakers.

By the end of the week, the will had been redrafted. The lawyer sent me a draft with words like residuary clause and bequest and all the language money uses to dress up the simple act of naming who matters. I signed where a line asked me to and wrote Grandma a note with fewer words and more meaning. She called me and said, “You’ll do beautiful things with it,” and we both pretended she had not cried when she said it.

Three months later, I stood in the penthouse that had felt like a prize and then a battleground and now felt like a choice. I had moved the furniture around and started buying fruit I used to think was indulgent. There were friends in my living room three times a week for dinners where nobody tried to sell anybody a single thing. My promotion had come with a raise and an award my CEO called “overdue,” which we both pretended had always been intended. I built a team full of twenty-somethings who reminded me of the version of me who thought wearing the same hoodie five nights in a row gave you superpowers, and I taught them how to say the word scope without losing friends.

The Carter name in Atlanta had taken a hit. People avoided my mother at luncheons because you can only hide under hats for so long. My father’s business found itself in boardrooms where discomfort had moved in, and a few contracts evaporated because sometimes a city remembers it has ethics. Tara’s wedding did not happen. Ethan sent a careful text with too many commas and not enough courage. She changed her Instagram bio to something about healing and started posting yoga videos filmed in my mother’s living room. I muted without malice.

I did not seek joy in their ruin. That is not the muscle I built. I built the one where you look at your own face in your bathroom mirror and say, “You do not have to leave yourself to be loved,” until it becomes a thing your body understands without language.

Grandma began to tell me stories she had not told my mother because history picks its listeners carefully. She told me about the time she worked in a dress shop on Peachtree and learned all the wives’ secrets and decided to have none of her own. She told me what it cost her to be the first woman on the board of the foundation that now underwrites the gala my mother loved more than me. She wrote me into her stories in a voice that had never written my mother into anything but chores and standards. I do not know what to do with that kind of gift except hold it and pretend it weighs nothing so it doesn’t hurt my hands.

Kayla and I took a weekend in Charleston where we ate oysters and talked about all the times we had made small choices that turned into large life. She stood in the doorway of a shop and said, “You know what you did? You turned down a table where they only served you if you apologized for being hungry and you built one where everyone eats.” I said, “That’s dramatic,” and then bought place settings for eight because sometimes friends trick you into matching your heart.

On a Wednesday in May, Grandma called and said, “I’m thinking of selling the beach house in Saint Simons; it’s too many stairs; I am not going to spend my last years fighting gravity.” We laughed the way two women laugh who know the joke is about age and about everything else. She told me I would inherit funds restricted to “nice splurges,” the phrase she used when she wanted us to understand permission. “Not taxes,” she said. “Not obligations. Nice splurges. Buy yourself something you’ve always refused because you thought you needed to earn it twice.”

I bought a piano with a company that delivered it on a Tuesday with men who apologized to it when they had to remove a leg. The first time I sat and put my hands on keys I had not touched since childhood, my fingers remembered a whole grammar my body had kept in muscle for the day I might want to speak again. I played badly and then less badly and then alone at night when the city outside decided to turn its noise down and I was left with the sound of my own hands making something that was not money.

By September, the sting in my cheek had been replaced by the memory of how cold the pearl had felt in my palm. I took it from the pouch where I had been keeping it and made it into a ring. Not an ostentatious setting. Just the pearl wrapped in gold, a circle that says, “This is mine now,” and “I know how to carry what I’ve been given.”

On a Sunday, my father called and left a voicemail. His voice had been sanded by months. “I am sorry,” he said. He did not ask to come over. He did not mention Tara. He said, “I am reading about boundaries.” I saved the message. I did not respond. Not out of cruelty. Out of patience. Out of the belief that some bridges should be crossed on foot, not with cars and apology baskets.

At Thanksgiving, I set a table in my own home that made sense: Kayla, her girlfriend, two colleagues whose families live north of where the cold starts, Grandma in the seat where she fits best, and Evan. He brought pie he had made with a tutorial and a desperation to do it right. He cried when we said grace because he is a Brooks and we are emotional when truth gets in the room. We did not leave chair spaces for my parents. We did not talk about the party months ago except to pass the salt in a way that felt like a sacrament.

Later that night, when the dishwasher hummed and I was alone with a sink of pots no algorithm has yet perfected a way to clean, I thought about the slap, the pearl, the cane, the will, the viral video, the way my cheek had betrayed nothing and my inside had broken open and then healed in a shape it liked better. I looked out at a city that had become a necklace of light and thought, “You kept yourself.”

I do not know the ending of every story in this room. I do not know if my parents will ever grow into the kind of people who could sit at my table without apologizing to fear first. I do not know if Tara will find something inside herself that is not a mirror. I do not know if my own heart will learn how to let my father try again without needing him to fail to verify my strength. What I do know is that I will never again hand my keys to anyone who has not first learned how to say my name without using it as a lever.

A week later, Grandma and I sat on her porch, the same porch where she had told me at nine, “You don’t have to be likable to be loved.” She looked at me with that sly little smile women who have lived through three kinds of century wear. “I’m selling the pearls,” she said. “They never looked right on me either.”

I held up my hand. “I took one,” I confessed. “I made it into a ring.”

Her eyes gleamed. “Good,” she replied, satisfied. “It always suited you better.”

We drank sweet tea. We watched the light change in the yard. We did not talk about estates. We did not talk about either of our daughters. We said a few words about what the city was doing with all those cranes and whether it would ruin the skyline or save it. We sat in the just-right space where love exists when you have stopped trying to buy your place in it.

When I finally left my grandmother’s house, she pressed a small envelope into my hand. “Nice splurge,” she reminded me. “Do not buy anything that makes your mother proud. Buy something that makes you sit down.”

I laughed out loud in my car in the driveway of a woman who had taught me how to become my own table. At a red light, I took a picture of my hand on the steering wheel with the pearl ring and sent it to Kayla. “I kept it,” I texted. She replied with a string of crown emojis because sincerity has found its own language.

On my way home, I drove a block past my parents’ building without deciding to. A woman very much like my mother but younger stepped out of the revolving door in heels and a storm of perfume. A man who could have been my father twenty years ago held it for her like a proof. Traffic moved. I moved with it.

Back in my own living room, I stood in front of the piano and played the same hymn I had played the night after I put my parents behind a door. My hands tripped in the same places and landed better in others. Out the window, Atlanta made that little sound it makes at nine p.m. in neighborhoods above Peachtree—the hum of dog walkers and dishes and all of us learning in small rooms how to be better at being each other’s home.

I thought about the first time my father put a microphone between himself and truth and later put his hand between him and me, and I thought about the last time my grandmother put her cane between him and power. I thought about a pearl in a pocket and a ring on a hand. I thought about how many times a woman has had to pick up a small round thing off a polished floor and decide to keep it. I thought: this is how we pass it down. Not money. Clarity.

The next morning, I met Kayla at a coffee shop where the barista knows I like my cappuccino with the honest amount of foam. She raised her cup toward me. “To penthouses you don’t give away,” she said. I raised mine. “To families we do.” And we drank in the way of women who know they will never again be the kind of daughters who get confused about the difference between a gift that is asked for and a theft dressed like tradition.

Part Two

Six months after the slap, Atlanta had learned my father’s name for the wrong reasons and mine for the right ones. The video had become case study and cautionary tale, a Rorschach test for what people think families owe each other. I spent most of that time doing the one thing nobody expects of a woman used to defending herself: I was quiet. Not silent—quiet the way you are when you are done arguing with rooms that won’t hear you.

Then the letters started.

My grandmother’s attorney, Whitcomb, phoned one rainy Tuesday as I shepherded a product launch that refused to acknowledge time zones. “Margaret asked that we move her estate work forward,” he said. “She’s made her intentions very clear, but your parents have signaled an intent to contest.”

“Of course they have,” I said, turning from the whiteboard where someone had drawn an octopus to represent technical debt.

“They’re alleging undue influence,” he went on, “citing the… party incident.”

“The one where my father assaulted me on camera and offered my home to my sister like a centerpiece?” I said. “That one?”

“That one,” he replied gently. “We’ll want to be thorough.”

Thorough is a language I speak. My spare room turned into a filing cabinet. Grandma Margaret, very much alive and delighted by the spectacle of outliving everyone’s expectations, signed affidavit after affidavit with a hand that never shook. Her internist wrote a letter using phrases like intact executive function and no evidence of cognitive decline. Her bridge partners sent a joint statement that made me cry from the way old women write about each other when nobody’s listening.

On the morning of the hearing, I wore a slate suit that didn’t apologize, the pearl ring catching weak winter light outside Fulton County Probate. Kayla squeezed my hand. “Remember,” she said, “you didn’t engineer this. You just stopped pretending not to notice it.”

My parents sat at the petitioner’s table behind their lawyer, a man who looked like he traveled with Scotch in his briefcase. His tie said old money, his expression said new problem. My mother wore beige, grief as performance. My father stared at the table as if it might feed him a line.

Judge Albright was exactly the kind of woman you want deciding what happens when families try to use love like leverage. White hair in a twist, readers low, eyes that have watched this movie before. Whitcomb began. He didn’t dramatize; he laid things on the table like tools. He filed Grandma’s current will, notarized and dated. He filed her prior will, so nobody could pretend this was a sudden swerve. He filed the doctor’s letter, the bridge notation, the list of philanthropic board meetings she’d chaired over the past five years, and then, with a little shrug, he filed a flash drive.

He did not have to play it. He did. Two minutes of the party—my father’s words, his hand, my grandmother’s cane. When it ended, the courtroom did the exact same thing the penthouse had done: inhaled as one organism and held.

My father’s attorney cleared his throat and said the words men say when the world finally sees a thing you’ve tried to talk them out of. “We have context,” he offered, and the judge said, “So do I.”

Grandma took the stand with a floral scarf and a smile for me that made me sit taller. “Mrs. Carter,” the judge said, “why the change?”

“Because I am eighty,” she answered, like a fact she enjoyed. “Because I have watched which of my girls learned to survive by making ladders and which learned to survive by asking for rope. And because you don’t hand your farm to the daughter who keeps forgetting to shut the gate.”

Whitcomb did not try not to smile. The other side tried to paint me as manipulative, as if women who know where their own paperwork lives are somehow suspect. It’s a very particular kind of misogyny—call it competent woman conspiring. It landed in front of a judge who had likely been called that herself and bounced off like a penny off a bank vault.

Ruling in hand, I walked out of the courthouse with Kayla and a sky that looked undecided. My mother sat on a bench by the doors, holding her purse as if it weighed more than law. She stood when she saw me. “Jenna,” she said, and then did something I had never seen her do in front of me: she looked twenty-five. “I don’t know how to do this.”

“Do what?” I asked. A morning jogger passed, the leash of his dog drawing a clean line between then and now.

“Love you without trying to control you,” she replied, the words surprising her as much as me. Behind her, my father stared out at the street like a man trying to decide which lane is exit.

“You could start,” I said, “by not asking me for anything right now.”

She nodded, once, like an apology practiced in private.

Work ate January 1 through March 1 with no concern for plot arcs. Our platform rolled out to three new clients. We survived a DDoS so elegant we printed the server logs and hung them in the hallway as cautionary art. I built a team that didn’t ask permission to call me “no” and meant it as a compliment. At night, I played the piano. Sometimes my phone would light up with GM and a painting of a peach; Grandma had taught herself emojis and used them like a raid on a candy store.

Tara texted once in February.

can we talk?

I stared at the little gray bubbles as if they were prophecy. They stopped, started, stopped. I thought of my pearl ring and of how women are trained to treat other women’s harm as an emergency more urgent than our own. I put the phone face down and finished playing Chopin badly on purpose.

She texted again the next day.

Ethan left. I deserve some of this. Not all of it. I’m in a program. I’m trying. That’s all.

I breathed in and counted to seven because my therapist says that’s how you make your brain stop trying to sprint while tied to a chair. I replied.

I’m glad you’re trying. Here are three therapists I recommend because they’re not interested in your Instagram bio. If in six months you are still trying, not just texting, we can get coffee.

Two blue checkmarks. No reply. Boundaries are not cruelty. They are a map when nobody else has one.

My father sent an email in March with no subject line and these three sentences:

I’m in anger management. It wasn’t for me at first and—this is not your job to process—my father hit me when I was a boy. It’s ugly to see yourself in the mirror someone else holds. I’m sorry.

I read it twice. I forwarded it to Kayla, who responded, “Apology accepted, sentence continued.” I wrote back to him, “Thank you for doing the work. I am not your accountability partner.” He wrote, “Understood.” We were both right.

If this sounds like a woman who has suddenly mastered detachment, imagine me standing at my kitchen counter at 11 p.m., eating cereal and crying into it because I do not know how to be a daughter when the father finally tries. I let myself be messy for twenty minutes and then wiped the counter and the bowl because both can be true.

Grandma asked me to lunch at her favorite café—lemon scones that will haunt you for days, waiters who call you “love” without sounding scripted. “You’re going to start a fund,” she said before the soup arrived.

“For what?”

“For women who are handed rooms like the one you walked out of and don’t have a Kayla or a piano or a backbone yet.” She pushed a folder across the table. “We’ll call it the Pearl Foundation because sometimes you have to make something pretty out of a wound.”

“You thought about this when I took the earring, didn’t you,” I said.

“I thought about this,” she replied, “the first time your mother cried in her bedroom when your grandfather told her she’d have to make do with whatever was handed to her. I failed her where I refuse to fail you.”

We built it in April the way women build things when they are tired of watching the world tell the same stories: fast, careful, with tea. We structured it to pay for three things: housing deposits for women leaving family homes that are no longer safe or sane, legal fees for injunctions and wills people don’t want to read, and scholarships for tech bootcamps because coding paid my rent when nobody else would. We hired a woman who had spent twelve years as a social worker and then burned out hard enough to leave an imprint on her desk. We listened to women say, “I shouldn’t be asking for this,” and taught them to ask louder.

On launch day, the website went live with a photograph of a ring on a keyboard and copy my marketing director wrote that made me proud to have hired her. Donations came in fast and then slower, the curve a reminder that the internet loves fresh hurt and is less interested in ongoing repair. That was fine. I didn’t need a viral moment a second time. I needed a pipeline. We had one within a week.

One of our first grant recipients, a woman named Amaya, moved into a one-bedroom with creaky floors and windows somebody’s grandfather probably put in. The first night on her own couch, she sent us a picture of her feet and a caption: I didn’t have to ask anyone to turn the stove off. I showed the photo to Grandma and she said, “I would have killed for that sentence in 1964,” and we sat there with our tea and let the world turn on a hinge you have to be a woman to notice.

In May, the invitation to the Carter Foundation Gala arrived and I almost laughed hard enough to pull a muscle. Grandma wanted to go because sometimes you have to sit in rooms you built and remind yourself you don’t need their validation to justify your furniture. She wore navy. I wore black. We looked like truth and elegy.

They seated us at Table Two, which means they wanted to punish us politely. My mother wore a headpiece far too festive for the season; grief had not been kind to her taste. My father’s tux fit differently, like a man whose body finally knows panic. Tara did not come. We learned from a whisper she had completed three months of inpatient treatment at a place with a name that sounds like a retreat but isn’t.

Sloan glided by and gave me the kind of smile women use when they are embarrassed for having backed the wrong horse. “You look beautiful,” she said. When the world turns properly, people get to say that to each other and mean it. “Thanks,” I said. “So do you.”

On the stage, a man my grandmother had once called “a hobby philanthropist” tapped the microphone and made a speech about legacy that used the word family more times than he should have. When he finished, the MC announced a surprise presentation and I nearly walked out on principle. I didn’t. They called my name.

I looked at Grandma. “Go,” she said. “Make them hear it.”

I stepped to a podium in shoes that were exactly the right height. In the room sat everyone who had brought the silent auction cake and everyone who had ever bought it. “We are taught to make ourselves available,” I said. “We are taught to make our homes available. We are told that the word family is a passcode that allows drunk uncles into our kitchens at 1 a.m. and allows fathers to call our homes blessings that can be redistributed at their discretion.”

Some faces went pale. Some went hard. A woman at table five put her hand over her mouth and then took it away as if she had been caught. “This year,” I continued, “my grandmother and I started the Pearl Foundation. We help women leave rooms like that. We pay the security deposit. We pay the lawyer who will read you the will you didn’t know had your name in it. We pay for you to learn how to write the code that will pay you, not the man who told you providing was aggressive. And if you need it, we will pay the therapist who will help you sit at your own table without setting yourself on fire to keep your mother warm.”

A few people clapped because some people know when a thing deserves it. Most said, “Hmm,” because some people need to pretend they are evaluating when they are recognizing themselves. I finished without asking for money because that was not why I had gone. I went to stand in a room with my grandmother and say out loud what had been whispered in kitchens for three hundred years. We left early and went home to lemon scones we had stolen.

June brought a text from Tara.

90 days sober. Found a job at a bakery. Using mornings to go to a group. I’m not asking you for anything. I just thought you might want to know I’m trying. Coffee?

I read it twice, then replied.

Proud of you. Sunday, 10 a.m. Corner table at Ezra’s. No earrings will be thrown.

She sent a laughing emoji, then a crying one, then a thumbs-up because sincerity is awkward until it isn’t.

We sat at a table two weeks later with coffee that tasted like the idea of starting over. She looked like someone who had run through rain. “I’m sorry,” she said without qualifying or bargaining. “For the party. For all the years before it. For not being your sister because being the favorite was easier.”

“You didn’t make that room alone,” I said. It felt like taking a heavy coat out of her hands. “You just learned how to breathe in it.” We sat with our coffee and our failure and our hope like three guests who showed up on time. I did not absolve her. I said, “You can bake for the Pearl Foundation event in August if you want. People think sweets will make them forgive faster. We’ll let them be right for once.”

She laughed. Her eyes did not.

August came. The bakery brought three sheet pans of something with cream cheese frosting people tried to pretend wasn’t perfect. Tara wore an apron and no mascara. Grandma sampled everything with the abandon of a woman who had decided moderation had wasted enough of her life. Kayla manned the donor table and made jokes about cookies for code. We raised enough to cover twelve deposits. We raised enough to keep me from thinking I had invented any of this.

On a Thursday in September, my father knocked on my door at dusk. I did not know it was him—I tend not to open doors to men who do not text first—until I checked the peephole and saw a man holding a bouquet from the grocery store like it might explode. His face looked like paper left in the rain.

“I’ll go,” he said through the door, “if you don’t want.” It was the first sentence he had ever said to me that offered me a choice before he needed it.

I opened. Kayla, who had been on my couch reading product requirements like a romance novel, stood without saying a word. “I’ll be in the guest room,” she said, and moved. Because friends who know the velocity of your heart know when to relocate.

He handed me the flowers and did not try to step inside without being asked. “I cannot fix it,” he said. “But I want to be a man who does not raise his hand when a woman says no to him.”

“Okay,” I said, because there is a place between forgiveness and exile, and it is sometimes the only place a daughter can live.

We stood in the doorway and he told me stories about his father I had never asked to hear. He said, “I am not asking you to teach me.” He said, “I am telling you how far I have to go so you can decide how far you can meet me.”

“I can meet you here,” I replied, touching the doorframe. “On the porch. With coffee.” He nodded, relief and regret making the same shape on his face.

He left. I put the flowers in water. Kayla came back to the couch and handed me my laptop. “I didn’t eavesdrop,” she lied. “But I added a card to the Pearl site for therapy for parents who are trying to unlearn.” I laughed and then cried and told her I was tired of making room for everyone’s redemption. She said, “We can have tea and still not let anyone rearrange the furniture.”

By October, the ring I had made out of a picked-up pearl had become less about defiance and more about quiet ceremony. When I turned my hand on a sunny morning while my coffee cooled and the light hit the curve just so, I thought about all the rooms in which I had made myself small and this one where I had not.

I started teaching Wednesday-night classes for the Pearl Foundation—Beginners’ Python for Women Who Have Been Told They Are Bad With Math. The first night, twelve women rolled their eyes at me and at the code equally. By week three, eight of them had written a script to parse their receipts and find the charges their exes thought they could hide. We cheered like women who had invented their own language. In a way, we had.

At Thanksgiving, I set a table with names taped to place cards I had made from algorithm flowcharts because we are allowed to make jokes we enjoy at our own table. Grandma sat in the seat with the good view. Kayla and her girlfriend argued with grace about whether it is okay to put marshmallows on yams. My father came for dessert with his sponsor and did not ask for more than the pie on his plate. Tara brought rolls that were almost as good as Grandma’s and that is exactly what a good life feels like.

After everyone left and the dishwasher purred, I stood at the piano and played the hymn I always play when I need to remember that this life begs for ritual. When the last note faded, I looked out at the city that had once felt like a superior jury and now felt like a neighbor.

I thought of the night three hundred people watched me say no and one man taught a room what happens when a woman finally does, and one woman with a cane rewrote her legacy around the granddaughter nobody thought would be sitting at this table.

I turned my ring once, a little habit that looked like nervousness and felt like gratitude. “You kept yourself,” I told the woman in the window. She nodded, like she had known all along.

END!

Disclaimer: Our stories are inspired by real-life events but are carefully rewritten for entertainment. Any resemblance to actual people or situations is purely coincidental.

News

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money’

‘I don’t understand why they are making such a fuss over that money,’ Brian Kilmeade passionately defended Erika Kirk on…

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent. CH2

Dad Pushed Papers Across the Table… But My Folder Made Him Go Silent Part One The rosemary lamb went…

BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions in his final statement and unexplained evidence have shocked the public: Is Robinson blaming someone else?….read more below

💥 BREAKING: Tyler Robinson’s first statement has just been released after he confessed to k!lling Charlie Kirk. However, the contradictions…

“I Stared At The Photo—My Son Did This?” — A Sheriff’s Father Breaks His Silence On Utah’s ALLEGED KILLER

At a $600,000 family home in Washington, Utah, a veteran lawman dialed the number no parent imagines: he turned in…

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire

The Rock’s Daughter Under Fire : Ava Raine, the daughter of Hollywood legend Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, has ignited one…

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale. CH2

My Husband Humiliated Me In Front Of His Entire Family—What My Daughter Said Next Made Him Pale Part One…

End of content

No more pages to load