My PARENTS Excluded Me From Grandpa’s Will Reading For Being “Ungrateful”—Then Lawyer Showed…

Part One

The hallway outside my grandfather’s study had always felt like a ship’s corridor—mahogany panels polished to a gloss, brass picture lights ticking quietly as if they kept their own time. As a child, I used to slide my hands along those walls, reading the little dents and scratches the way some children read Braille, telling myself I could hear the house’s memory. That morning, the shine made everything colder. I stood there with my coat clutched like a shield and listened to the muffled cadence of Mr. Abernathy’s baritone flow and break on language that had never before included me as fully as I wanted: bequeath, devise, in fee simple.

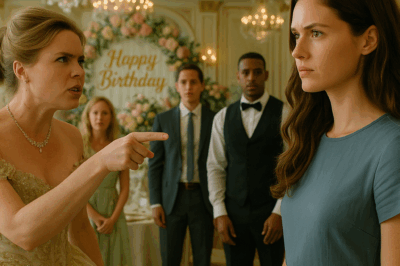

The door to the study was shut. My mother’s palm was flat against the carved panel, a pose I had seen in paintings of queens forbidding entry to supplicants. “You aren’t welcome,” she said without looking at me. Each syllable clicked like crystal. “Your grandfather was very disappointed in your choices.”

“Disappointed in my choices,” in our house, was code for didn’t take the job at Hayes Capital, didn’t marry a man who could afford the Christmas photo, didn’t reduce her curiosity to quarterly returns.

David stood behind her shoulder with that cultivated, unearned expression of magnanimity he wore when he wanted to hurt me gently. “It’s for the best, Becca,” he said, as if he were inviting me to a spa treatment. “Grandpa wanted his legacy in the hands of family who appreciate it.”

“Appreciate” was a dagger disguised as a word. I had flown back from London on a ticket booked with the last of my savings. I still had the crisp ache of airplane air in the back of my throat and the weight of the jet lag like wet wool. I had come anyway: because grief is a compass, because there had been times in my grandfather’s study when the desk lamp’s glow had pooled on parchment like forgiveness, because I had a memory I needed to put my hands on before it left.

Inside, Mr. Abernathy’s voice went on, punctuated by little paper sighs as pages turned. Around me, the family—our aunts, our identical gray uncles, spouses who had learned to nod at the right line—flowed past, avoiding my eye like I’d become a painting whose subject made them uncomfortable.

When the door finally opened, Mr. Abernathy stepped into the hall with his attaché and that expression of near-sorrow the best lawyers wear when they have done their duty and the consequences have begun. Behind him, the room smelled like leather bindings and old smoke—the ghost of my grandfather’s pipe, disapproved of by my mother and indulged on winter evenings when the windows fogged.

“Rebecca,” he said softly, and the use of my full name was not meant to scold but to steady. “Your grandfather insisted you receive this privately.”

It was a small, sealed envelope with my name in his neat, architectural hand. I knew the slant, the way he formed his R like the leg of a table. I had watched him address letters on Sunday afternoons while lunch plates cooled in the dining room and my father checked the markets even on sabbaths.

I slit the flap with my thumbnail and slid out a single card.

My dear Rebecca,

My greatest treasures were never on a balance sheet. They are in the history we shared. The key is where our journey began.

I read it twice more, the second time hearing in my head the way he used to say the word history, not as if it were dusty but as if it were alive and might turn its head when you called it. I didn’t see my mother’s hand until it flashed across my vision and plucked the card out of my fingers.

“More of your sentimental nonsense,” she said, reading it as if it were in a language she refused to learn. “The estate is settled. David is in charge now. You can go back to your dusty old paintings.”

David looked past me down the hall, already measuring where the new runner would go. “We’ll discuss a small stipend, Becca. In good time.”

“We don’t discuss stipends,” my father said, appearing at my mother’s shoulder with the tired annoyance of a man who believes equity is a word for accountants. He put a heavy hand on my coat, not affectionate so much as directional. “It’s time to accept your place, Rebecca. You made your choices.”

They said it like a verdict. I felt the case file closing. I also felt, shockingly, the little spark of the other memory the note had struck. “Where our journey began” was not a metaphor. It was a place. More precisely, it was a room in the local museum with a raised platform and a glass case and a small plaque I had memorized at nine years old: Harding Gallery: Maps of the Old World.

My grandfather had believed you hid things where people would be proud to display them. “A secret in a secret calls attention to itself,” he used to say, flipping the latches on the 17th-century Florentine desk he had bought at auction in a flurry of delight I had never again seen in my family’s house. “A secret in a story? People will pay to see it and never know you have it.”

We wrote letters to each other after I moved to London. Not emails—letters. I sent him pencil rubbings from brass memorials and postcards of manuscripts that had survived centuries and carelessness. He sent me inked notes and questions he knew would make me look harder. In between, we drew a map of a desk.

It was a magnificent contraption: ebony veneer, gilded accents, drawers within drawers, pigeonholes behind columns, tricks and jokes the craftsman had built into it like winks. My family saw the desk as a balance sheet entry with an insurance rider and an impressive backstory for house tours. My grandfather saw a history lesson you could touch. He believed it had a hidden compartment—a segreto—an idea that had set us both alight. He believed something important was in there. “Not for them,” he had said without rancor, meaning my father and brother and the hungry cousins. “For you. For us.”

Where our journey began: the museum. The Harding Gallery. Room 5. The map case on the right, second row, where a 17th-century cabinetmaker’s demonstration key has sat under glass for a decade—wooden shank, iron tooth, label: Key, Italian, c. 1620. It was a good place to hide a thing no one would look at twice.

I drove to the museum in a rental car that smelled like lemon and disappointment. The curator on duty was Alice, who had been my intern once before I left for London, all bright hair and blinding competence. Mr. Abernathy had called ahead, she said; there was an envelope in the safe, left with instructions seven years ago: on the death of M. Harding, to be released to Ms. Rebecca Hayes only.

The key was heavier than it looked. Its iron bit was more complex. The wood had a thread of grain that matched the desk’s in a way you only saw when your eyes had been taught to notice the way a story repeats itself across materials. I thanked Alice and drove back to the house at dusk with the old brass house key my grandfather had given me—“For the quiet times”—carried like a talisman in my pocket.

The study was dark when I let myself in. The desk sat under the lamp as it had for forty years like a patient animal. The keyhole we had suspected hid in a garland of carved leaves. I knelt, slid the iron home, and turned. The soft click when the panel eased out was the sound of someone giving up a secret with relief.

Inside: vellum that had smelled like cotton the last time I had leaned over such papers. Deeds. Hand-drawn maps. Seals unbroken. Names written in hands I recognized not because I had seen them before but because I knew the way people wrote when they believed the future had made promises to them.

The land was ours. More precisely, it was mine—granted and conveyed through an old private trust line that ran next to the company incorporations and never touched them. It wasn’t just a nice field with a view. It was the ground under half the firm’s most profitable projects: the parcels the company had built on and built its pride on and its press releases on. The ownership chain, established separately from the corporate estate, turned the house of cards my family had been building into a deck that could be reshuffled by one hand.

Below the deeds in the compartment was a letter from my grandfather. He wrote plainly. He always did when something mattered. He explained the conveyances, the trust he had formed quietly after watching his own son named to a board that talked about legacy as if it were a brand campaign. He wrote, Some men think the land is theirs if they can point at it from a balcony. It belongs to the person who reads it. Make a place for people to learn the difference.

He had signed it with the flourish that looked like a mapmaker’s flourish on a compass rose.

I called Mr. Abernathy. He came at dawn with coffee and eyebrows slightly lifted above his glasses in cautious admiration. We sat on the floor with our backs against the desk and he explained words to me I had seen in his mouth but not in my knowing: separate personal bequest, inter vivos trust, corporate estate, chain of title. He knew the law; I knew the way a cabinetmaker in Florence had hidden a compartment so well that only a child who loved old things and a grandfather who indulged her would think to look.

“You understand,” he said, spreading the deeds like tarot, “that this will not only alter the balance of the firm; it will alter the myth your family tells about itself.”

“I think,” I said, hearing how calm my voice sounded in my own ears, “I am finally ready to tell a chapter.”

What people who have always been included forget is how steady you can become when your whole life has been a rehearsal for the moment you are allowed into the room with the mic. I waited. I let them crow. I let David send his text: We can arrange a small annual stipend for your living expenses. Out of respect for Grandpa’s memory. I sent back a thumbs-up pinched so tight it could have been read as toying or capitulation. My mother sent me an article about a women’s networking group she thought I might find helpful now that my “London life has run its course.” My father asked for my address “to send something from the estate”—which arrived as a gift card to a chain store that sells shelves and systems.

Mr. Abernathy suggested the annual shareholders’ meeting. “If we file the notice of interest the week before,” he said, “we can’t be ignored. If we do it at the meeting, we can’t be misrepresented. If we do it at the end, they won’t have time to regroup.”

“I have always hated ambushes,” I said. “That’s how they do things. Not how we do things.”

“It won’t be an ambush,” he said. “It will be a reading.”

We retained an appraiser Mr. Abernathy trusted because he had once spotted a forged seal in a case that had landed a developer in prison. We retained a historian because I had asked for it and because the firm could not bully a professor into changing a date the way it could bully a surveyor into changing a boundary line. We retained a conservation lawyer because even as I was writing my speech, I was writing a grant proposal in my head.

Then we waited for the day.

In the auditorium that had hosted three decades of quarterly revelations, my brother took the stage in a suit that made him look like a successful idea and talked about liquidity events and rightsizing and the best way to unlock trapped value. I sat in the third row with my coat folded in my lap and listened for the part where he said love, history, archive, land, we belong to it as much as it belongs to us. It did not come.

When the chair opened the room to questions, Mr. Abernathy rose in the aisle and asked if he might, on behalf of a new majority shareholder, pose a question of clarification. The chair’s eyebrows went up in a polite arc. He had seen surprises before. He had never seen this one.

“New what?” David said into the mic with the practiced delight of a man who loves an audience too much to hide his disdain.

“A new majority shareholder,” Mr. Abernathy repeated, his voice very mild. “I would like to introduce Ms. Rebecca Hayes.”

There is a sound a room makes when its narrative changes. It isn’t a gasp, exactly. It is the removal of one set of assumptions and the scramble to pick up another. I walked to the podium with my grandfather’s letter in my pocket and the deeds in a portfolio that had once carried slides for a paper about 15th-century pigment.

I did not look at my mother. I did not look at my brother. I looked at the land on the map projected behind me—the squares and lines of a city that thinks it invented itself. I told a story. The audience did not expect a story. They expected a fight. I told them instead about a cabinetmaker in 1620 who fashioned a desk with a compartment so well-hidden that only someone who had spent hours running her fingers along the carvings, looking for the flaw in the ivy, would find it. I told them my grandfather had loved ledgers but loved libraries more. I told them that a will is one way to write a legacy and that a separate trust with a separate chain of title is another, older way—one made of ink and land and a little stubbornness.

Then I showed them the deeds. They weren’t pretty. The paper had browned to a color that made you think of old lace; the seals had cracked. But their lines were clear. Chain-of-title lawyers and geographers had already overlaid them on modern maps. The room saw it: the way the land my grandfather had held apart held up the firm’s public projects and balance sheet letterheads. The way his separate gift did not undo the corporate estate but made anyone who thought they owned that myth recalibrate how they spoke about it.

“We will not be selling,” I said, and a man in the fourth row laughed in disbelief and then didn’t when he saw my appraiser shake his head at him very gently. “We will be stewarding. There is money there, yes. But there is more than money. There is the chance to make my grandfather’s love of history part of this city’s future. We will partner with a conservation trust. We will create a public park on the section by the river where the trees have been waiting to grow big again for seventy years. We will build a small museum on the parcel by the old train line—a place where people can read documents instead of press releases. We will lease responsibly. We will reject offers that confuse profit with purpose. In other words, we will make the word legacy mean something measurable with a calendar and a field guide, not just an investor deck.”

It is possible to feel the moment a myth collapses. It doesn’t always break; sometimes it just deflates like an expensive balloon, quietly losing the air that made it impressive. I watched my brother’s face as he realized that his power had been built on land he did not own and a story he had not written. I watched my father look at my mother with the helplessness of a man who has just realized his reading of his own life has been too narrow and too loud. I watched a few board members sit forward with the greed of new opportunity; I watched a few sit back with the relief of not having to be the kind of people they had become at work.

When I finished, I did not ask for applause. I asked for quiet. “I know many of you didn’t come for this,” I said. “But I think my grandfather did.”

In the dark of the auditorium, Mr. Abernathy’s mouth twitched at one corner. That man enjoyed a good clause. He enjoyed, too, the satisfaction of an elegant plan revealing itself without anyone needing to get an ulcer in the hallway.

I did not return their calls that night. Or the next. Or the week after, when the financial pages ran the headline that made me both blush and roll my eyes: Curator Heir Reshapes Hayes Legacy With Historic Claim. The comments sections were exactly as kind and cruel as you’d expect. A stranger in Minnesota wrote that I looked like I needed a sandwich. Another said his daughter had cried when she read there’d be free admission on Sundays. My inbox was full of art students, conservationists, and one former corporation lawyer who confessed she had quit her job the day after a man like my brother told her that maps were “just art.”

David sent a single text after the meeting. It was not contrition. It was strategy. You’ve embarrassed us. Fix it. I archived it. My father called and said, “We should have a family conversation about this.” I told him what I had been telling him since I was twelve: that I would be delighted to talk once he learned to listen. My mother wrote a letter that began with, “I don’t know where we went wrong,” and ended with a recipe for roast chicken. In the middle, she said, “You always thought you were special.” I wrote back the only thing I knew was true: “I think everyone is.”

I did not keep the land untouched. I did not freeze it in amber. I did not turn the museum into a shrine to me or to my grandfather. Mr. Abernathy’s conservation lawyer—who wore her hair in a braid thick as a rope and spoke in a voice like weather when it has made up its mind—helped me write a covenant that outlives our pettyness. We put trails where people could walk without ruining the salamanders’ spring. We restored a marsh that had been a parking lot. We built a reading room with long tables and light that fell like mercy. We taught children how to handle 18th-century paper with their clean small hands. We planted oaks whose shade I will not live to see and wrote a plaque that made it not about us.

On opening day of the park, the mayor cut a ribbon, and the paper ran another photo of me that made a man in a comment section say something about my shoes. A boy who could have been me at eight arrived with a field guide and a backpack. He ran through the stand of new trees with his arms out like wings and then stopped short and put his palms on a railroad tie we had left in the ground like a vein, whispering, this was here before me. A woman brought her grandmother and her lawn chair to sit at the edge of the river where the weeds used to be. A teenager fell asleep under a maple with his hoodie over his eyes. The reading room filled with a quiet that was not the silence of being shamed. It was the kind of quiet that sounds like a possibility drawing breath.

Mr. Abernathy came to the museum opening in a suit that had been pressed by someone who loved a crease. He touched the desk, lightly, the way you touch a dog who is still learning to trust again. “He would have liked this,” he said.

“He would have loved the fact that Landry from Facilities finally found the missing caster for the bottom drawer,” I said, and Mr. Abernathy laughed, full and loud, a man who had not been allowed to laugh in that house for years.

At the end of the day, after the last child had been extracted from a book with promises of ice cream and the woman with the lawn chair had folded it neatly and promised to return every Tuesday, I walked to the edge of the park where the boundary fence met the road. A car slowed; my mother’s face flickered in the passenger window, turned toward the trees. She did not roll down the glass. She did not wave. She looked. It was more than she had given me in months. I raised my hand. She raised hers, halfway, like a person opening a door in her mind and thinking better of it. The car moved on.

There is no forgiveness scene here. There is, perhaps, the slow work of a family learning how to be people who deserve new chapters. That takes longer than headlines and doesn’t often produce copy. My brother will probably not become someone I invite to read a land acknowledgment at the park fundraiser. He will probably forward that email to a junior associate with the note We need to be seen at this. I will probably let him buy a table and then assign his seats next to the salamander display. We will all learn from the amphibians.

Late that night, with the park quiet and the museum dark and the desk asleep with its secrets spent, I went back to the study in the house where it had all begun. I sat at the desk and wrote a letter to my grandfather on the back of a copy of the deed to the smallest parcel: the one with the wild pear tree that had bloomed even when no one remembered to look. I told him I had kept the promise he had written to me in iron and ink. I told him they had called me ungrateful and that the lawyer had shown them the difference between owning something and knowing it. I told him I had met a boy who whispered to a railroad tie and that the tie had whispered back.

When I finished, I slid the letter into the desk’s top drawer and smiled at my own impulse to hide it. I shut the drawer. The click felt like a door locking. Not to keep anyone out. To keep something in.

On the way out, I ran my fingers along the wall in the hall outside the study like I had when I was little. The house did not feel like a ship anymore. It felt like a book that had been put back on the right shelf.

In the parking lot the next morning, a woman in running shoes asked the docent where the bathrooms were without whispering as if that were a disgrace. A man in a suit sat under a tree and took off his shoes, setting them neatly side by side in the grass. A group of teenagers took selfies with the map of the land overlaying the city grid, and in three of their photos you could see me in the corner, smiling, which is how I know someone will someday tell a story about the day the curator heir made a park out of a will and an apology out of a museum and a beginning out of a secret compartment.

It is not the inheritance my family wanted. It is, finally, the one we deserved.

Part Two

The first week after the shareholders’ meeting, the house phones stopped ringing. My email inbox, which had been a bright aquarium of family messages and dutiful CCs, went dim like someone had pulled a cloth over the tank. In their place: messages from city planners, professors wanting class visits, teenagers asking about internships, and—my favorite—a nine-year-old with a signature that said “Librarian in Training” requesting a map of “the salamander trails.”

The quiet from my parents and David chalked its own lines. Silence can be weapon and salve. This one was both. It left a ringing in my ears—what now?—and room enough to lay the first stones of what we’d promised.

The first unexpected stone was legal. David filed for an injunction the following Monday. “Unclear chain of title,” his lawyer argued, “and undue influence over an elderly man by a granddaughter who stood to benefit.” The phrase undue influence crawled over me like something that feeds in the dark. It made me so angry I had to go outside and walk the fence line of the park-in-progress until my jaw unclenched.

Mr. Abernathy kept me from saying anything we couldn’t back up with a footnote. “We anticipated this,” he said, sliding a copy of the trust across his desk like a chess move he had practiced in his sleep. “They have optics; we have documents.” He tapped the signature witnesses: the museum curator, the conservation lawyer, the old family friend who had been counting tree rings with my grandfather on Sundays.

In court, the judge—soft-voiced, sharp-eyed—listened to two days of the Hayes family trying to eat itself and then asked one question that took the oxygen out of David’s argument: “Where, exactly, in this narrative, is the evidence that this woman is not her grandfather’s intellectual peer?” They had none. We had letters, notes in the margins of centuries-old texts with our two hands making the same mistake on a date and correcting it in the same ink.

The injunction failed. I walked out into a February sun so brittle it sounded like breaking glass, and for the first time since I’d unlocked the desk, I slept six hours without waking up on a breath that felt like it had lost its way.

Work is a good anesthetic when family has been the wound and the trigger. We started with the marsh because the salamanders didn’t give a damn about paper victories; their spring tunnels wouldn’t wait for my brother to learn the difference between equity and heirloom. Restoring a wetland in a city isn’t poetic. It’s mud to the knees, rebar out of the muck, volunteers whose enthusiasm outpaces their understanding of where not to step, a conservation lawyer who points with a stick and says, “Here. Exactly here.”

We held our first plantings on a chilly Saturday in March. The mayor showed up in brand-new boots and sank to the ankle on his second step, which did more for the city’s affection for the project than any press release could have. I watched a board member—one of the “rightsizers”—stand knee-deep in the sediment, handing out ferns with the reverent focus of someone meeting a child. On the trail above us, two teenagers documented the entire thing for their environmental science class and then for a social channel where they would be ridiculed for their earnestness by the very algorithm we were trying to teach them to read as history.

The reading room came next. We kept the walls plain. We let the light tell the story. We set long tables with enough room for elbows and arguments. We designed the policy in active verbs: turn pages with clean hands; ask for help; return what you take out into the world. On opening day, the little brass bell at the front desk rang so much we had to explain to a child that it wasn’t a toy but a signal. He nodded solemnly and then asked, with catastrophic sincerity, if he could be the one to ring it “when the past needs help.”

In June, a teenager in a hoodie fell asleep with his head on a folio box. We didn’t wake him. A woman with a scarf printed with saints came every Tuesday to read land records with a magnifying glass and cry once an hour, quietly, like someone moving through a prayer. A retired sanitation worker parked himself under the maple tree at noon every day and read aloud to anyone who would sit: the newspaper, a pamphlet on lichens, the hand-lettered sign we made explaining why the salamanders had the right-of-way in April. Each new voice made the place feel less like something I had to defend and more like something I could tend.

David tried again in summer. A white-envelope letter with glossy letterhead, full of words like amicable and reasonable, pretending we hadn’t both just been in court. He offered a buyout; he couched it as mercy. Mr. Abernathy read it once, made a sound like a sleepy bear, and slid it across to me. “He’s still negotiating with the story in his head,” he said. “We’ll reply to the one on paper.”

We did, with courtesy. The courtesy cost me an afternoon and the desire to eat. My mother called the next day—not to talk about the letter but to ask if she could host her book club in the reading room “because Constance wants to see what you’ve done and the chairs at the club make her hip hurt.” I told her the reading room was a public place, not a stage for regretted parenting arcs. She said she didn’t understand the tone I was using. I repeated the address of the park, as if she had never learned to find a thing unless it was framed on a wall.

“Your brother is a mess,” she said abruptly, as if I were one of her friends and we were trying on responses. “I don’t know why he’s doing this.”

Because he hates losing, I thought. Out loud, I said, “We each have something we can’t stand to see smashed. Maybe this is his.”

“And yours?” she asked, surprising me.

“Being made invisible,” I said, surprising us both.

She didn’t argue. She changed the subject to what I ate for breakfast.

In August, Mr. Abernathy retired. He came to tell me himself, holding his resignation letter like an exhibit. “I wasn’t sure how to say it to your family,” he admitted, looking almost sheepish. “But to you, it seemed easy. I am tired of listening to men pretend the terms of a thing are unjust simply because they don’t like them.” He had already found us a younger partner—Asha—whose bracelets chimed like cicadas when she gestured. She read the trust documents once and handed them back with a nod that felt like a blessing. “This is good work,” she said. “Let’s keep it boring.” Legal boring is a gift you don’t realize you need until chaos knocks loud at predictable intervals.

The chaos knocked again that fall. Anonymous op-eds appeared in the city paper warning of “legacy land grabs” turning a family firm into a “pet project of a curator.” The first one got share traction from that subset of people who resent losing access to the back gate and confuse the feeling with civic outrage. The second one included a photo of me mid-sentence, mouth open, which gave strangers the courage to speculate about everything from my haircut to my character. A third never ran because the editor—whose mother had been reading saints in our reading room—wrote back with a request for the writer’s sources. They didn’t have any that could stand up to a librarian with a pen.

“Reduce your oxygen intake,” Mr. Abernathy had told me in June when I brooded for two days on a comment thread that called me a word I hadn’t heard since middle school. “Starve them with patience.”

He was right, though late-night discipline is a muscle; it shakes if you put too much weight on it without training. Asha told me, practical as an invoice, “Reply once. Facts only. Then go plant a tree with a child.” I did. The child did not care about op-eds; he cared about worms. He taught me the sound a spade makes when you hit a stone.

The year turned. The park browned, then crisped. Winter came with a steely rain that polished every path and made the salamander tunnels into rivers. We closed the trails. People yelled at the signs. Two teenagers broke the rule and posted a video of themselves running through the closed wetland at dawn; the comments on that one were the kind the previous op-eds had tried and failed to pull. Social shame is often the quickest corrective. The teenagers came in two days later with baked goods and an apology and an enthusiasm for watching volunteer docents yell marsh facts that made me feel less like a scold and more like a choir conductor.

On the anniversary of my grandfather’s death, Mr. Abernathy—retired now, still unable to resist a fillip of dramatic staging—brought me a book. It was a ledger, its lines filled not with debt but with donation: checks scribbled to neighborhood libraries, small grants to historical societies, notes to himself about the price of a book he’d been outbid on at a sale in 1978. Tucked into the back cover was a letter in another hand entirely, older, looping—my great-grandmother’s. Hold the line, Michael, she had written to my grandfather when my father was a boy and had announced he would rather mow lawns than read Dickens. One of them will hear you. That is a family.

I sat in the study with the ledger and the letter and realized that while my father had only ever seen money as the proof and the point, my grandfather had kept a separate accounting: things given, promises kept, pages turned by small hands.

I took the ledger to the reading room and put it under glass with his note to me about the desk and the key. A little girl stood on tiptoe to see it and said, “Does that mean she was his mom?” pointing at the letterhead.

“Yes,” I said.

“Did she tell him what to do?”

“She told him what to stand for,” I said. The little girl considered this and nodded, wise as a bell.

Two winters after the will reading, I saw my mother on the path by the river. It was Sunday. The air was sharp. She was walking slowly, her coat buttoned all the way up against the kind of cold that makes you aware of your ankles. She didn’t see me at first. She was reading a sign we had installed near the fence line with the firm—David’s firm; I still didn’t say it without thinking of my grandfather’s voice—explaining where the old boundary stones lay under the grass.

“I always thought those were just rocks,” she said without turning when I stopped beside her. The old sarcasm pricked at the edge of our conversation like a thorn. She didn’t use it.

“They were,” I said. “Now they’re also page numbers.” She smiled, the quick one that used to appear before she caught it and ironed it flat. We stood in silence, the kind that does not hurt.

After a while, she said, “Your father comes every Wednesday afternoon. He doesn’t like to see you.” She met my eyes. “Not yet. He says he doesn’t know how to stand there and look at what he chose and what he didn’t. He always did better with numbers than with looking.”

I let out a breath I hadn’t admitted I was holding. “Does he read the signs?”

“He pretends to read them.” Her mouth quirked. “But yesterday he told me that oaks take a hundred years to make their own weather, so yes. He reads them.”

She put on the scarf she used to wear to church as if the park required a similar respect. “There’s a book club I want to host in your reading room,” she said, like a woman asking for a cup of sugar from a neighbor she had once feuded with across a fence. “If you’ll have us. We’d rather speak softly in a place that makes us.”

I thought about the night she had blocked the door with her palm and called me ungrateful. I thought about a ledger filled with gifts. I thought about a boy whispering to a railroad tie. “There’s a sign-up sheet online,” I said. She looked relieved by the bureaucracy and smiled again, small as a truce.

After she left, I watched her walk past the salamander tunnels, heed the sign, and choose the higher path.

David did not come to the park. He sent a card at Christmas that read, For the children’s fund at the museum, with a check inside that would have covered a round of new pencil sharpeners and a case of sticky notes. He addressed it to “Ms. Hayes.” He did not sign his name. Asha rolled her eyes so hard I thought she’d sprain something. “Donate to the salamanders,” she said dryly, “and we’ll consider a commutation.”

We never got the salamanders’ approval on our legal strategy. We did get their number in the spring count: up, slightly. It felt like an acquittal.

On the third anniversary of the park’s opening, we hosted a field day we called “One Square Mile of Story.” The event poster—designed by a high schooler, approved by a grandmother, resisted by a board member until we asked him to read it aloud and he fell in love with the way mile and smile made the same shape—went up in every café window and church foyer for four neighborhoods. There were stations for oral histories, a corner for people to bring old deeds and letters (scanned while they watched, explained while they listened), a marching band of third graders who wheezed through Sousa like a promise, a cake shaped like a map that children ate as if they could absorb the grid and call it theirs.

Just as the band was getting to the part where you could either clap or cry, I saw him: my father. He stood at the edge of the crowd like someone who had taken off his shoes to wade into water and was deciding whether to go all the way in. He wore his only casual coat—an old tweed he had bought in a fit of nostalgia when I announced I was going to study abroad—and a face I had last seen on him the day he told me I should do what I loved and then watched me do it and realized he didn’t know how to speak that language.

He waited until the marching band went out of tune and the cake was cut and the children with sticky hands and mouthfuls of geography had run off. Then he walked up to me and held out a file. It was so theatrical a gesture I laughed, and then I read the label: “Hayes Capital — Land Use Advertising Concepts.” Inside: a dozen drafts—David’s firm had been planning a campaign to normalize buying right up to the edge of our covenant. The slogans were frightening in their skill: “Heritage Housing,” “Park-Adjacent Progress,” “Stewardship You Can Live In.”

“I found these in an office where they shouldn’t have been,” my father said. “I don’t want you blindsided.”

“Why?” I asked, not sarcastic, not gentle—something else. Clarifying.

He looked toward the map cake with a slow smile he had always saved for the rare times I made a joke he understood. “Because I did not hold the line with you early enough. Because your grandfather did. Because I see, finally, that you were not against us. You were for something we had misnamed.”

We stood with the file between us until the band restarted with heroic bravery and the third graders found a rhythm that would have made a general cry. “We have covenants,” I said. “And Asha. And salamanders.”

“I know,” he said. “I just wanted to be on your side publicly for once before I die.”

“Don’t be dramatic,” I said, and we both laughed, startled and relieved. He put a hand on my shoulder—heavy, directional once, now lighter, less sure of its right—but I didn’t shrug it off.

He didn’t stay long. He doesn’t like crowds. He went and stood by the railroad tie as if it were an altar and I watched him touch it with two fingers the way he did the holy water font when he still went to church.

“Forgiveness isn’t a scene,” Asha said to me later, washing cake plates with a competence that made me want to sit down. “It’s a policy change.”

“Add that to the covenant,” I said.

The day the saint-reader brought her book club, my mother came with them. They talked about land and grief and the way cities bury marshes under parking lots and call it progress. They read a chapter from my grandfather’s ledger and a few lines from a man who had written, in 1854, about the way a river in winter looks like a thing keeping a promise.

Afterward, my mother waited until the room cleared out and said, “I wanted a child who would carry the firm.” She looked at the desk and the window and the shelves we had made to look old because we had honored something it took money to hold and didn’t deserve to be called cheap. “I got a child who carried a story. It turns out the story was stronger.”

“That doesn’t excuse what you did,” I said.

She nodded. “It explains it,” she said. “A little. Apologies are thin if they are only words. What do you need?”

“Help,” I said, and we both smiled at the oddness of that in our mouths. “People think free museums run on air. They run on docents and book menders and someone to cut apples for children who have never been allowed to eat in a room like this.” She laughed—this time without catching it—and came on Tuesdays with apples and a knife and a patience for children that surprised even her.

We didn’t speak of my brother. There are losses you acknowledge quietly, like stone you build around so it looks like you planned a bench. He sent a letter on firm letterhead six months later proposing a joint initiative to install tastefully branded signage throughout the park extolling the virtues of “intergenerational vision.” Asha wrote back with a one-sentence reply and an invoice for unauthorized use of trademarked language in a public space. He paid the invoice the next week. He knew how to read, too, after all. He just preferred a different genre.

On the fifth anniversary of the shareholders’ meeting, I stood with Mr. Abernathy and Asha on the ridge above the marsh and counted salamander egg masses with a scientist whose enthusiasm for amphibians made me feel less like a fool for loving paper. The number had gone up again. Not much. Just enough to feel like a research note in a ledger that being human had taught me to keep. Mr. Abernathy wore a hat with earflaps and recited to me the clause number in the conservation agreement that guaranteed the city couldn’t widen the road for at least fifty years.

“You think I need reminding?” I said, grinning.

“I think you like company,” he said, grinning back.

We watched a group of third graders march past—bagpipes this time, god help us—and I thought of my grandfather at his desk, hiding deeds inside a story and then telling me where to find them. We had used the thing he loved to save the thing he loved. Not with force, not with a takeover, but with a reading. The lesson was a map; the map became a park; the park taught the city to be less impressed by press releases and more impressed by salamanders.

That night, when the reading room had emptied and the last docent had turned the bell on its side and thrown the light switch twice because old habits reassure old bones, I sat at the Florentine desk with a piece of paper and a pen that had belonged to my great-grandmother. I wrote a letter to a girl I do not yet know—nine, maybe, hair in a plait, hands ink-smudged. I told her where to find the key to the next thing we will have to hide in plain sight. Not money. Not paper. A sentence I have learned by practicing it:

You don’t owe your family a myth. You owe them a story they can live in.

I slid the letter into the desk’s top drawer. I did not hide it. I shut the drawer with a click that echoed like a promise kept.

On my way out, I ran my fingers along the hallway. The house felt less like a ship. It felt like a book that would stay on the right shelf even if you stopped guarding it, because enough people had learned how to read it and would not let it be misfiled. Outside, the park breathed that low sound trees make when they are old enough to believe in their own weather. Somewhere in the dark, a salamander moved under leaves and did not know it had been the subject of a legal brief. That’s my favorite part of all of this: the creatures who do not care about our narratives and in so doing, save us from our worst stories.

At the gate, a woman in a coat buttoned up against the cold was waiting with a child who hopped from foot to foot in a rhythm that made me think of the marching band. “Are you Rebecca?” the woman asked, and when I nodded, she said, “My daughter wants to bring her class here. We wondered about Tuesdays.”

“We are always open on Tuesdays,” I said, and the bell in the reading room rang in my head as if someone had called the past over for help and it had answered, “I was waiting.”

END!

News

My Father Gave My Inheritance to His New Wife’s Son, but the Truth Came Out at the Lawyer’s Office. CH2

My Father Gave My Inheritance to His New Wife’s Son, but the Truth Came Out at the Lawyer’s Office …

Bride Overhears Groom’s Shocking Betrayal, Returns to Wedding with Ultimate Revenge. CH2

Bride Overhears Groom’s Shocking Betrayal, Returns to Wedding with Ultimate Revenge Part One I didn’t plan to become the…

My Sister’s Birthday Cost 180k$…My Hotel. Seeing Me, She Said, ‘Kick This Homeless Person Out. CH2

My Sister’s Birthday Cost $180K… My Hotel. Seeing Me, She Said, “Kick This Homeless Person Out.” Part One It…

At breakfast, my husband threw coffee on my face when i refused to give my credit card… CH2

At breakfast, my husband threw coffee on my face when I refused to give my credit card… Part One…

At my wedding, my mother-in-law declared, “the child she’s carrying belongs to another man” CH2

At my wedding, my mother-in-law declared, “the child she’s carrying belongs to another man” Part One I can tell…

I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” ch2

I Missed My Flight, And A Fortune Teller Gave Me A Silver Needle: “Check Your Husband” — So I… …

End of content

No more pages to load