My parents evicted me from the apartment I was renting from them, so my pregnant sister and her fiancé could move in. Six months later, they came asking for help since I’d stopped paying rent. But instead of cash, I mailed them this letter from my sister.

Part One

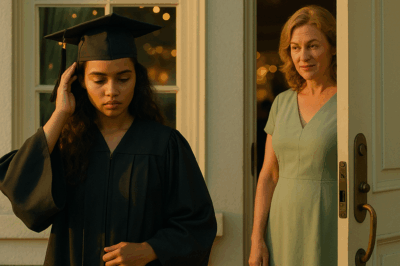

My name is Tamara, and I had just turned twenty-two when I earned my degree in business administration. People think the tassel turn is the end of a race. It’s not. It’s the beginning of noticing who cheers because you’ve crossed a finish line and who is already building the next hurdle.

I’d been lucky during college—lucky in a way I later learned is just another word for complicated. My dad inherited my grandmother’s old apartment after she passed three years earlier, and I moved in. It wasn’t free; I paid utilities, scraped together the internet bill with tip money from Luigi’s two blocks away, and rolled coins to keep the lights on when midterms devoured my hours. On more nights than I can count I closed the restaurant, walked home with my feet singing the alphabet of pain, and wrote papers with a bag of frozen peas on my arches. I did it because it felt like the thing adults do: handle it.

Graduation dinner at my parents’ house smelled like gravy and applause. Mom outdid herself—roast, salad with the good olives, her cinnamon rolls that could make a monk break a fast. Emily, my seventeen-year-old sister, made jokes about how she’d miss me editing her essays. Relatives came—Aunt Sarah and Uncle Bob, my cousins Mike and Jenny, Nana from my mom’s side. People gave me cards with fifty-dollar bills folded in them and advice that sounded like fortune cookies. I hugged and grinned and filed it all away with the practiced efficiency of a girl who budgets even for joy.

After everyone left, the room thinned out. Mom cleared her throat in that way she always does before delivering news that sits like a stone: the throat-clearing of report cards and curfews and the day we had to put our dog down. It was a sound my body remembered before my brain did; everything inside me went still.

“Tamara, honey,” she said, voice formal like she’d put on heels. “Now that you’ve graduated, we need to discuss the apartment.”

I set down my coffee cup very carefully so it wouldn’t clatter and betray the shake in my hands. “What about it?”

“Well, if you want to continue living there, you’ll need to start paying rent.” She smiled in what she thought was a softening way. “Not market rate, obviously. A family discount.”

Dad studied his mug. Emily pretended her phone contained the cure for loneliness, but I could feel her attention like a light on the side of my face.

“I see,” I said, small voice, big room.

The math toasted my nerves as we talked numbers. It wasn’t cruel, not exactly. I was an adult now; adults contribute. The timing, though—on my graduation day—cut. It said in the subtext my family always spoke: you will be celebrated, but you will never be allowed to rest.

That night back at the apartment, I pulled off the black heels I’d borrowed from Aunt Sarah and applied ice to my feet while scrolling job listings. Luigi’s couldn’t give me full-time. I needed salary, benefits, the kind of paycheck that stretches all the way to the end of the month without panting. I sent résumés until my fingers cramped.

The next year was a conveyor belt: pay stub, rent transfer, receipt file; weekday emails, weekend laundry; adults who used to be professors; coworkers who used to be strangers. I landed a junior account coordinator role at a small marketing firm near the apartment. The salary didn’t roll in like a wave, but it came steady as rain, and that was enough. Every month I transferred rent to Mom’s account and often tacked on a little extra “for utilities,” though she never asked. Part of me wanted them to know I was dependable. Part of me was still that kid who won the school attendance award because she thought showing up would always be noticed.

Emily dropped by sometimes, a hurricane of perfume and borrowed clothes, wanting me to tweak her application essays or to ask if navy goes with black (it does now; fashion is a circle). She’d become a mystery to me—more secretive, more theatrical. It’s a familiar arc for youngest children who learn early that attention is oxygen. She started dating Jason: nineteen, a year older than her, working part-time at the electronics store in the mall. He had that shininess some boys get when their only experience of plans working is when other people make them. The first time he came over he yanked my fridge open without asking and said, “You got anything to drink besides water?” It wasn’t a felony. It was a forecast.

The phone call that changed the temperature in my life sounded normal when it came. “Tomorrow, come over right away,” Mom said, voice tight. “Important.”

“Emily’s college?” I guessed. She’d been nibbling the edges of decisions. I imagined budget spreadsheets, scholarship forms, good-daughter advising.

When I arrived, the air in the living room had that shimmer of staged calm. Mom and Dad sat on the sofa like they were on a committee. Emily perched on the armchair in a way that would make chiropractors sigh, her mouth styled with a smirk I recognized from childhood as the face she wears when the next line is “We’ve decided.”

“Sit down,” Dad said, voice rough like sandpaper. He looked older, a whole decade older, the way men do when pride and fear spend too many nights wrestling inside them.

“Emily is pregnant,” Mom said bluntly. The room did its slow-motion trick. I focused on the ottoman seam to keep from floating off. Mom’s hands twisted in her lap—old habit, young grief.

“And,” she continued, smoothing her skirt as if that could smooth what was coming, “she and Jason will need a place to live. They’ll be moving into the apartment.”

“What?” My voice cracked, a bridge I hadn’t reinforced. The apartment was home. Not fancy—my couch was an old friend’s castoff and the dining chairs wobbled if you breathed wrong—but it was the life I’d assembled, piece by piece, with tip money and patience.

“You’ll need to move out,” Mom said, matter-of-fact, checking it off like a grocery item. “It’s the perfect solution. The apartment’s already furnished. Good neighborhood. Close to Jason’s parents.” Emily glanced down at her nails with exaggerated interest. She’d “borrowed” my sweater again, I noticed—the good one I’d said yes to only because I was too tired to fight no.

“How long do I have to find a new place?” I asked, fists pressed hard into my thighs out of their line of sight.

“A week should be enough,” Mom said. Then, like a magician producing a rabbit that is somehow a knife: “Oh, and you’ll continue paying rent.”

I laughed. I couldn’t help it. It escaped up and out, a bark that sounded like a stranger in my own mouth. Mom’s face didn’t move.

“You can’t be serious,” I said.

“Your sister and Jason are young,” Mom replied in that patient tone she uses when she believes she’s being reasonable. “They don’t have jobs yet, and with the baby… ”

“If they’re old enough to have a baby, they’re old enough to get jobs,” I said. “Have either of them even applied for anything full-time?”

“How can you be so selfish?” Emily whined, tears gathering like she’d scheduled them. “I’m going to be a mother. Don’t you care about your niece or nephew?”

“You’re being ungrateful,” Mom said, voice going arctic. “After everything we’ve done for you.”

“I’ve been paying rent for a year,” I said. “I’ve worked since college. And now you want me to support two adults who won’t support themselves? I won’t pay a cent for them. If you want to enable this, that’s your choice. Count me out.”

I left with their words—ungrateful, selfish—snapping at my ankles like small mean dogs. The door thudded behind me, an end punctuation I could feel in my bones.

That night I packed. Not in a week. Not later. That night. I boxed my books in neat alphabet piles because order felt like oxygen. I wrapped my coffee maker—the one I bought with my first work bonus—in old T-shirts because it felt like a friend. I labeled everything I’d purchased with a Sharpie because I’d learned that in this family, proof is the only language that lands.

By noon the next day I’d found a studio across town with peeling paint and a slanted floor that made my dresser insist on scooting overnight like it had places to be. I signed the lease. It was tiny, and the bathroom tile was old enough to vote, and the commute would be longer, but the key in my palm was heavy with one truth: this is mine.

When I finished moving the things I owned, I slid my apartment key under my parents’ door. No note. Every word I could think to use had already been shot down.

Mom called three days later and screamed. “What did you do to the apartment?”

“Everything there when I moved in is still there,” I said calmly. “I took only what I bought. You know that because you saw the receipts when I sent you my rent. Maybe Emily and Jason can try buying things the way I did.”

She called me names I’d never heard pass her lips. I hung up before the part of me that still wants to be a good daughter could pick up those words and build a house out of them to live in forever.

I cried that night in my new place. I allowed it the dignity of space. Not the gasping kind—this wasn’t heartbreak; this was surgery. I grieved the version of my family where I could call my mother when the lightbulb in the hallway wouldn’t unscrew. I grieved the sister who used to paint my nails. I grieved the story that working hard always lets you keep the things you’ve earned.

Then I did what I’ve always done: I worked. Work is a relief when feelings are a mountain. Sarah, my boss, noticed I was the one who would take the client crisis call at 2 a.m. without sighing. She noticed that I could be counted on not just to show up but to think. She stacked responsibilities on my desk and I lifted them. One month I realized I’d gone whole days without checking my phone because the only people I wanted to talk to were right there.

I was promoted—more money, more respect, a little office with a window that faced a brick wall but still let in a slice of sky. I opened a separate savings account named “down payment,” and every time I moved money into it I felt like I was sending little future me love notes.

Information about my family arrived filtered through social media and Aunt Sarah, who has always been the town crier in our small town even when the town didn’t ask to be cried to. Emily had the baby—boy, pink skin and dark hair like Dad’s. Pictures went up: Jason in a hospital gown grinning like he’d just invented fatherhood, Mom with that anesthesia-of-love look new grandmothers get. I studied the photos with the clinical curiosity of a person trying to feel and coming up with data instead. I clicked “like” because civility costs nothing and sometimes buys you peace.

Months later an email pinged my inbox: Emily.

Hey sis, it read, as if the last year were an intermission and not the second act. Heard you got a promotion. Congrats! We’d love for you to meet your nephew—he’s such a precious angel and I know you’d love him. Also, here’s his wishlist. There was a link and then a bulleted list long enough to be a catalog: designer onesies, a stroller that cost more than my first car insurance premium, silicone bibs in colors that sounded like paints—sage, terracotta, ocean—and a high-tech baby monitor system that could probably detect earthquakes.

I closed the list. I typed: Are you working yet?

The reply came as if she’d been waiting with a finger on “send.” Mom and Dad are taking care of everything. They give us spending money. We’re focusing on being parents. It’s such important work, you know.

Then the punch: We’re thinking about more kids soon. Mom and Dad are such suckers—that is, so supportive. They’ll have to keep helping if we have more babies. And we want a big wedding too. Nothing cheap. Those old fools will pay for everything.

I read it three times. Each read peeled another layer off whatever was left of my denial. My sister, whom my parents had wrapped in bubble wrap since birth, had grown into a person who said “old fools” about the people who had stood on their feet for decades to give her a life without calluses. She’d become a strategist of dependency.

I didn’t respond. There is no “Reply All” for chasms.

Two months later Mom called. I watched the screen light up with “MOM” and let it ring three times while I told myself that the person I used to be would answer and the person I was now would not. I picked up because curiosity is stronger than grief sometimes.

“Tamara,” she said, voice rough. “We need to talk. Can you come over?”

What is it about the words “we need to talk” that make you revert to twelve? I went.

They looked older. Not in that tender way people you love age. In the way people who have been stealing from their own sleep age. Dad’s hair had gone gray behind his ears. Mom’s knuckles were chapped like she’d suddenly started doing the dishes of eight people. The house was clean in the way homes are clean when no one has the energy to clutter.

“We’ve been taking extra shifts,” Dad said, and in his mouth the words were an apology stapled to a threat. “To help your sister. To help Jason.” The clock ticked in the silence like it had something to say about time wasted.

“We know you’re doing well at your job,” Mom said carefully, and I felt the duct tape stretch across my chest. This wasn’t an apology. This was a new invoice. “We think it’s time you helped support your sister too.”

I laughed. I couldn’t stop it. It was a good laugh; it came from my feet.

“You want me to what?”

“Your sister can’t work,” Mom said, annoyed I hadn’t accepted my assignment. “She has the baby. It’s a full-time job.”

“What about Jason?” I asked. “Is ‘full-time job’ a phrase he knows?”

“He needs to help with the baby,” Mom said, like a person reading from a cue card.

“Let me get this straight,” I said, pronouncing each word like a different instrument in an orchestra. “You’re working extra shifts to support two people who decline to work. And you’d like me to participate in this… subscription.” I wanted to say “pyramid scheme” but thought perhaps saving my jokes for later would make them land harder.

“You’re being selfish and greedy,” Dad said, color rising. “If you don’t help support your sister, consider yourself disowned.”

“You can’t disown someone who already left,” I said, which was both a line and the truth, and I walked out.

Back home I made tea, not because I needed it but because the ritual calms the mammal. Then I opened my laptop and pulled up Emily’s email: old fools, more babies, nothing cheap. I stared at the forward button. A tiny, picky voice in my head objected—the one that still believes family secrets are a kind of sacred paper you don’t burn. But the ethical math resolved: people wielding your silence as a weapon don’t get to quote confidentiality at you. I forwarded the email to Mom. No commentary. Raw truth doesn’t need garnish.

Mom didn’t reply. A week later Aunt Sarah called because of course she did. “You won’t believe it,” she said, and then didn’t wait for me to disprove her. “Your parents kicked Emily and Jason out. It was a scene.” She narrated the night like a sports broadcaster. Mom, calm in a way that scared everyone. Dad, finally done. Emily, a hurricane of tears and “no one understands me.” Jason, a statue at the wrong museum.

Two hours later my phone lit up with “EMILY.” I let it go to voicemail and listened to the message of weeping that could win awards for sound design. I called her back because I am fair even when I shouldn’t be.

“Can we stay with you,” she sniffed, “just until we figure things out? Please?”

“No,” I said. It felt like yoga for the soul.

“You’re just like them!” she screamed. “Selfish!”

“Family doesn’t exploit family,” I said, and hung up.

Aunt Sarah filled in the epilogue: Emily and Jason moved in with his parents. His mother—according to every thread in the family gossip tapestry—was a serious woman who believed in chores and schedules and “if you have time to scroll you have time to sweep.” She required contributions to the grocery budget, and when Emily said “I have a baby,” his mother said, “So do I. He is thirty-two and he does laundry.” I enjoyed the symmetry more than I should have: the universe doing remedial parenting on my behalf.

On my next birthday, I blew out candles in my own kitchen. Not the studio anymore—six hundred days of discipline had piled up into a down payment and a set of keys. I’d bought a two-bedroom walk-up with creaky stairs and a balcony barely big enough for a chair. I painted the second bedroom a gentle blue and called it “the office” even when all I did in there was read and not be anywhere else. Friends sang off-key and clinked glasses and asked questions about my life instead of saying “How could you?”

Mid-dessert, the doorbell rang. A courier. A small box. The return address: my parents. Inside, a silver frame like the one I’d admired once, long ago, when Mom and I were in a shop where the saleswoman called us “ladies” like we deserved it. There was a card: We’re sorry. We miss you. When you’re ready, we’d like to talk. Nine words and all of history attached to them.

I put the frame on the coffee table without a photograph inside it. The empty rectangle said exactly what I felt: space where the picture goes, but not yet.

Part Two

The week after my birthday the city shifted into late-spring mode. Kids played street baseball with a level of seriousness grownups should envy. My block smelled like cut grass and someone else’s barbecue. Work flourished. I was managing my own small team now. I hired an intern who reminded me of me at nineteen, except braver—she said “no” in meetings without apologizing first. I applauded that every time.

On Tuesday nights I sat in the back of the Meridian Community Center’s big room where folding chairs go to multiply. I’d gone first as a guest, then as a volunteer, to a group for seniors—not just seniors, really; anyone—who’d been financially exploited by family. We told the truth there, in complete sentences, and the room didn’t crack. Diana, the coordinator, introduced me one night as “someone who understands the economics and the emotions,” and I realized with a small shock that I had become a person with expertise in surviving my own family.

One night a woman named Brynn came in and stood by the door like she was trying not to enter a church in case it caught fire. I sat next to her and whispered, “We do first names. No one has to tell their whole story. You can just listen.” She nodded, a tiny shift, like the first inch of movement in a car that’s been parked a long time.

I told my story the way you learn to tell stories in rooms like that: the facts lined up on a plate, not flung like confetti. I left out my best lines. I kept in the numbers. People snapped in solidarity the way theater students do when clapping feels too loud. Maxine, seventy-two with the posture of a ballerina, said, “I thought I was crazy. Turns out I’m just generous and tired.” Everyone laughed softly. Rosa, sixty, said, “I forgave my son. Then he did it again. I am now forgiving myself instead. It feels like taking off shoes that are two sizes too small.”

Six months after the eviction I stopped calling “the eviction” and began calling “the time my family taught me who they were,” my parents asked to meet. “At the diner,” Mom said. Neutral ground. We sat in a booth where the plastic protests against human skin in summer. Dad ordered coffee. Mom ordered tea but didn’t drink it.

“We shouldn’t have asked you to keep paying rent,” Dad said, looking at the sugar packets. “We shouldn’t have kicked you out like that,” Mom said, looking at me only on the last word. “We put ourselves in a corner,” Dad said. “We thought if we could just get through the first months, they’d… ” He trailed off. Hope as a drug.

Mom slid a letter across the table like a played card. It was the one I’d forwarded. Emily’s words, printed. old fools in ink. I don’t know what I expected to feel. Satisfaction, maybe. I felt weary. It is exhausting to be proven right about the worst things.

“We’re sorry,” Mom said. “We thought we were loving her. We were creating a person who can’t stand.”

“I accept your apology,” I said. “And I’m not ready to come back to that version of family. I need boundaries. And I need you to respect them.”

“What do those look like?” Dad asked, and for once it sounded like a real question.

“No financial entanglements,” I said. “No guilt. If you want a relationship with me, it’s about us. Not about me being a bridge to Emily.” They both nodded. We did not hug in the parking lot. We didn’t need to. Sometimes a nod is a signed contract.

A week later I got a text from an unknown number that turned out to be Jason’s mother, Carmen. We haven’t met. I want you to know your sister is safe, and we are doing what your parents should have done years ago. She’s learning to budget. She’s learning to parent. If she turns herself around, it will be because of structure, not spending. The text was not an olive branch. It was an update. I replied: Thank you for doing the hard thing. She wrote back: Someone did it for me. Pay it forward when you can. I put my phone down and thought about how women pass invisible lessons down in ways that don’t come with scrapbooks.

At work we pitched a national client on a campaign about integrity. I stood at the front of the room and talked about brand trust and consumer protection and gave examples that had nothing to do with my mother. We got the account. My team took me to lunch and toasted with iced tea. I felt very adult and also nine years old and everything in between, which is to say: I felt like a person.

“Are you going to meet your nephew?” my friend Kara asked one night over wine on my tiny balcony. “I don’t know,” I said. “I only want to meet people I can meet without first duct-taping my wallet shut.”

Two months later Mom texted a photo of Emily at a parent-teacher night for a baby class where they teach you to swaddle with a towel and hope. Emily’s hair was pulled back; her face was bare of armor. She looked… young. My heart did a weird thing that hearts do: it thudded with equal parts anger and love. I did not reply. The next morning I forwarded the photo to Michael with a question mark. He wrote: She’s trying. On purpose. It’s small and it’s real.

Autumn came, again. The light in my living room shifted from “post-work nap” to “read books and refuse all invitations.” The silver frame still sat empty on the coffee table, an honest placeholder. Sometimes I tucked a postcard into it, or a grocery list, or a recipe I wanted to try. The emptiness was not an accusation now. It was permission.

Around Thanksgiving, the community center asked if I’d help with a financial literacy class for high schoolers. We talked about compound interest and budgeting and how debt isn’t a moral failing but can become a very rude roommate. A girl in the front row with glitter on her cheeks asked, “How do you say no to your mom if she asks you for money and you have it?” The room went still in that way rooms do when the honest question arrives disguised as a hypothetical.

“You write down your rent and your groceries and what you need for emergencies,” I said. “And if there’s something after that, you decide what you can give without resentment. If the answer is ‘none,’ you say, ‘I love you and I can’t right now.’ You will not enjoy saying it. You will survive.”

“Will she still love me?” the girl whispered.

“She will still be your mom,” I said. “And you will still be you.”

In December, when the city glittered on purpose, I got an envelope in the mail addressed in Mom’s handwriting. Inside was a note: We are hosting Christmas. You are always welcome. There will be no conversations about money. I went, not because Christmas demands attendance but because I wanted to test the new bridge we were building. We ate ham and potatoes and things with marshmallows in them. Emily was there with the baby—my nephew—who had two teeth and a laugh that sounded like the first day of spring.

“Hi,” Emily said quietly when we ended up next to each other at the sink. “I got a job.” She swallowed. “Part-time. At the clinic Carmen volunteers at. It’s not glamorous. I clean instruments. I stock the supply closet. I go home smelling like bleach.”

“How do you feel about it?” I asked.

“Like I did when I learned to ride a bike,” she said. “Mad that I had to try so hard. Unbelievably proud when I didn’t fall.”

“I’m happy for you,” I said, and it wasn’t a performance. I dried a dish. She washed another. We didn’t solve anything. We didn’t break anything either.

On New Year’s Day, my phone buzzed with a text from Aunt Sarah that said, Look at you. It was a screenshot of a local newspaper article about our community center’s program and a photo of me, mid-sentence, hands making a shape in the air like I was trying to hold space. The caption read: Neighbors Help Neighbors Set Boundaries. I sent the link to Mom and Dad. Mom responded with a heart and the words So proud. Dad wrote Knew you would. I laughed and cried at the same time because the sentiment was cable television but the feelings were premium.

In March, Carmen invited me to a small birthday party for my nephew. “In our backyard,” she wrote. “Hot dogs and cupcakes. No fuss. If you come, you come. If not, another time.” It was the exact invitation I needed: free of strings. I went. We ate store-bought cupcakes. The baby smashed his like it owed him money. Emily watched him with a look I recognized: the one faces get when love arrives dressed as work. She caught my eye across the yard. She tapped her heart. I tapped mine.

One afternoon, months later, Mom and I were on my balcony with iced tea sweating into coasters. “Do you ever think about the apartment?” she asked.

“Less now,” I said. “Sometimes I miss the window light at 4 p.m. Sometimes I miss the smell of the hall in summer. Mostly I am grateful I learned what I can live without and what I can’t.”

“What can’t you live without?” she asked.

“My keys,” I said. “My work. People who choose me without making me pay at the door.”

She nodded. “We did a number on you,” she said, not fishing, not punishing herself, just naming.

“We did a number on Emily,” I said. “We all did.”

“We’re trying,” she said. “I told your father if either of us so much as thinks the words ‘family discount’ about rent again, we have to do pushups.”

“That’s funny,” I said. “That’s healing.”

In late summer, I bought a dog. A small brown mutt with eyebrows and a sense of humor. I named her Penny because copper looks good on her and because change, nine out of ten times, is worth it. Penny loves my balcony like it’s a private park and barks at pigeons with the confidence of a creature who thinks noise is a solution. She has taught me to wake up and walk even when my brain built a blanket fort.

A year and a half from the day I carried my boxes down the stairs from a place I’d thought was mine, I mailed my parents a letter. Not a text. Not an email. Paper with my handwriting on it. I told them about my work, about Penny, about the way the light in my living room makes homework easier for the girls from the center who sometimes sit at my table and figure out how to say “no” in their own mouths. I told them what boundaries look like now, like furniture I move to suit my life. I told them: I will not loan money to Emily or host her if she is using guilt as a suitcase. I will come to dinner if there are no financial ambushes. I will leave if old habits put on new coats. I will love you. I will not pay rent for anyone’s life but my own.

Mom wrote back. We can do that. Dad wrote, See you Sunday. I’ll make cinnamon rolls. He did. They tasted like when I was seven and didn’t know a thing about power of attorney or “family discount” rent. We ate in the kitchen. The dog licked the floor. The baby—no longer a baby—ran in circles, which is his job and he is good at it.

Later, at home, I opened the drawer where I keep important papers. Deed. Insurance. The silver frame card. Emily’s email—the one with old fools—sat in the back in a sleeve. I slid it farther under the stack. I don’t need it as armor anymore. It’s a record, not a shield.

The letter I mailed my parents the day they asked me to help support my sister, instead of cash, was simple. It was printed on ordinary paper. It said only this:

Mom, Dad, I can’t help in the way you’re asking. I can’t fund the consequences of choices I didn’t make. But I want you to see something you haven’t seen, or haven’t let yourself see. This is from Emily to me. Her words, not mine.

I attached a copy of Emily’s email—the one where she called them old fools and outlined a life plan that replaced work with womb. It was the harshest kindness I’ve ever committed. It was also a boundary with a stamp on it.

Months later, over cinnamon rolls, Mom looked at me and said thank you. Not sorry. Not I wish we’d known. Not how could you. Just thank you—for lighting a fuse that burned away the story they were telling themselves about love and replaced it with one about choice.

I am not naïve. Families don’t pivot like ballerinas. They lurch like ships. But we are pointed at something better now: Emily learning the math of labor, my parents learning the grammar of no, me learning the art of staying without disappearing.

The frame on my coffee table finally holds a photograph. It’s not a diploma or a family portrait. It’s a picture of my living room with sun flooding the rug, Penny asleep on her side, and my nephew on the floor next to her, stacking blocks. If you look closely, you can see my hand in the corner, steadying the tower—but not holding it up.

That’s the ending I owe the girl who once believed being good would be enough: a life where help is offered, not extracted; where rent is paid to landlords, not to guilt; where the letters we send are not threats or pleas, but truths that stand even when no one claps.

And if anyone asks how it turned out when my parents came asking for help because I’d stopped paying rent, I tell them this: I didn’t wire money. I mailed a letter. And in the blank space where cash might have gone, a different kind of inheritance grew.

END!

News

After I refused to pay for my daughter’s over-the-top wedding, she stopped speaking to me. ch2

After I refused to pay for my daughter’s over-the-top wedding, she stopped speaking to me. A few days later, I…

VIRAL: Kayleigh McEnany’s baby Avery’s FIRST trip photo SHOCKS fans with a intriguing detail!

Kayleigh McEnany’s Heartwarming Reveal: Third Daughter’s First Trip Photo Stuns Fans with Shocking Detail! Fox News star Kayleigh McEnany…

At my birthday dinner, my sister announced she was pregnant with my husband’s child. ch2

At my birthday dinner, my sister announced she was pregnant with my husband’s child. She thought I’d fall apart. We’re…

Can you even afford this place? My sister sneered loud enough for nearby tables to hear. ch2

Can you even afford this place? My sister sneered loud enough for nearby tables to hear. She laughed, sipping her…

My parents left me at a train station as a joke. Let’s see if she can find her way home. ch2

My parents left me at a train station as a joke. Let’s see if she can find her way home….

At my graduation party, I was told to wait outside the venue. My aunt smirked, “This is just for close family.” ch2

At my graduation party, I was told to wait outside the venue. My aunt smirked, “This is just for close…

End of content

No more pages to load